WALT WHITMAN and the WOBBLIES a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Was Sparked by Walt Whitman's “I Sing the Body Electric”

Collins !1 Joey Collins Honors Senior Seminar Dr. Blais & Dr. LeBlanc 9 December 2018 The Lightning in Us: What Was Sparked by Walt Whitman’s “I Sing The Body Electric” Poets and historians of American literature have closely analyzed the contents of the great American poem “I Sing The Body Electric” by Walt Whitman. To comprehend the underlying messages conveyed in this work, one must understand how Whitman’s musings relate to the his- tory of, as well as the present incarnation of American culture. Whitman himself was a man of his own, defying the cultural norms of his time and expressing through his poetry a unique view of our nation. His expression in “Body Electric” is telling of his individuality as a poet and a nineteenth century American man, and this expression has proven itself to be timeless as it is revered in today’s America. The America of now is a vastly diverse melting pot of political views, personal back- grounds, and cultural fusions. “Body Electric” is an all-encompassing poem, written from the perspective of Whitman the careful observer, who is able to see the inherent beauty in the many interweaving constituents of our country. As the poem unfolds, there is a decidedly political stance taken by Whitman, a stance which, one hundred and sixty three years after the poem’s publishing, still reads as contentious in our modern social climate. It is this contentiousness com- bined with a freshly delivered ode to the many colors of our nation that gives the poem its au- thenticity. Collins !2 The title of the poem perfectly indicates its conveyed viewpoint. -

Walt Whitman, Where the Future Becomes Present, Edited by David Haven Blake and Michael Robertson

7ALT7HITMAN 7HERETHE&UTURE "ECOMES0RESENT the iowa whitman series Ed Folsom, series editor WALTWHITMAN WHERETHEFUTURE BECOMESPRESENT EDITEDBYDAVIDHAVENBLAKE ANDMICHAELROBERTSON VOJWFSTJUZPGJPXBQSFTTJPXBDJUZ University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 2008 by the University of Iowa Press www.uiowapress.org All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Richard Hendel No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The University of Iowa Press is a member of Green Press Initiative and is committed to preserving natural resources. Printed on acid-free paper issn: 1556–5610 lccn: 2007936977 isbn-13: 978-1-58729–638-3 (cloth) isbn-10: 1-58729–638-1 (cloth) 08 09 10 11 12 c 5 4 3 2 1 Past and present and future are not disjoined but joined. The greatest poet forms the consistence of what is to be from what has been and is. He drags the dead out of their coffins and stands them again on their feet .... he says to the past, Rise and walk before me that I may realize you. He learns the lesson .... he places himself where the future becomes present. walt whitman Preface to the 1855 Leaves of Grass { contents } Acknowledgments, ix David Haven Blake and Michael Robertson Introduction: Loos’d of Limits and Imaginary Lines, 1 David Lehman The Visionary Whitman, 8 Wai Chee Dimock Epic and Lyric: The Aegean, the Nile, and Whitman, 17 Meredith L. -

!V(-Q WALT WHITMAN

!v(-q v( THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS THE ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BIRTH OF WALT WHITMAN AN EXHIBIT FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF MRS. FRANK JULIAN SPRAGUE OF NEW YORK CITY 4 I A LIST OF MANUSCRIPTS, BOOKS, PORTRAITS, PRINTS, BROADSIDES, AND MEMORABILIA LI IN COMMEMORATION OF THE One Hundredand Twentieth Anniversary OF THE BIRTH OF WALT WHITMAN [MAY 31, 1819-19391 FROM THE WHITMAN COLLECTION OF MRS. FRANK JULIAN SPRAGUE OF NEW YORK CITY I EXHIBITED AT THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 1939'3 FOREWORD ti[THE YEAR 1939 marks the one hundred and twentieth anni- versary of the birth of Walt Whitman. As part of the celebration of that anniversary, the Library of Congress exhibited a collection of material from the magnificent Walt Whitman collection as- sembled over a period of twenty-five years by Mrs. Frank Julian Sprague, of New York City. This material was selected and pre- pared for exhibition by Dr. Joseph Auslander, Consultant in Poetry in the Library of Congress. The Library of Congress is unwilling that this exhibit should terminate without some record which may serve as an expression of its gratitude to Mrs. Sprague for her generosity in making the display possible and a witness to its appreciation of Mrs. Sprague's great service to American poetry and to the American tradition of which Walt Whitman is not only the poet but the symbol. Many of the books in Mrs. Sprague's collection are unique, some are in mint condition, none is unopened. The greater part of the collection, including the two paintings which were done from life, has never before been exhibited to the great American public for which Whitman wrote and by which he is remembered. -

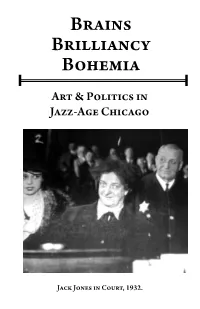

Brains Brilliancy Bohemia

Brains Brilliancy Bohemia Art & Politics in Jazz-Age Chicago Jack Jones in Court, 1932. PUBLISHING INFO CONTACT INFO ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This publication and accompanying exhibition would not have been possible without the support of several organizations and individuals, most significantly the Newberry Library, whose extensive collection of Dill Pickle related materials, provided much of this publication’s content. I would also like to thank Lila Weinberg, Tim Samuelson and Mess Hall for their exceptional support and generosity. Introduction f you walk by Tooker Alley, the unmarked alleyway between Dela- ware and Chestnut off Dearborn Street in Chicago, it looks not unlike many other alleyways in the city. Passersby would have little Ireason to stop and take notice of the parking lots, dumpsters and back porches of the adjacent townhouses. And yet 80 years ago, Tooker Al- ley was nationally known as home to Jack Jones’ notorious Dill Pickle Club. This club served simultaneously as a tea room, lecture hall, art gallery, theatre, sandwich shop, printing press, craft store, speakeasy and one-time toy manufacturer — and just about the most curious venue in the known universe. And so goes the dependability our collective memory. The non-remem- brance of the Dill Pickle reminds us of which histories are kept alive and which are lost to the dustbins. Our historical amnesia also recalls the importance of preserving the stories of our social movements for future generations. This booklet documents one such effort: a re-circulation of ephemera from The Dill Pickle Club, one of the most creative, politically engaged and influential American cultural centers of the 20th Century. -

John Burroughs for ATQ: 19Th C

THE HUDSON RIVER VA LLEY REviEW A Journal of Regional Studies MARIST Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Marist College Editors Reed Sparling, writer, Scenic Hudson Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Editorial Board Art Director Myra Young Armstead, Professor of History, Richard Deon Bard College Business Manager Col. Lance Betros, Professor and deputy head, Andrew Villani Department of History, U.S. Military Academy at West Point The Hudson River Valley Review (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice Susan Ingalls Lewis, Assistant Professor of History, a year by the Hudson River Valley State University of New York at New Paltz Institute at Marist College. Sarah Olson, Superintendent, Roosevelt- James M. Johnson, Executive Director Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Roger Panetta, Professor of History, Research Assistants Fordham University Elizabeth Vielkind H. Daniel Peck, Professor of English, Emily Wist Vassar College Hudson River Valley Institute Robyn L. Rosen, Associate Professor of History, Advisory Board Marist College Todd Brinckerhoff, Chair David Schuyler, Professor of American Studies, Peter Bienstock, Vice Chair Franklin & Marshall College Dr. Frank Bumpus Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President of Academic Frank J. Doherty Affairs, Marist College, Chair Patrick Garvey David Woolner, Associate Professor of History Marjorie Hart & Political Science, Marist College, Franklin Maureen Kangas & Eleanor Roosevelt Institute, Hyde Park Barnabas McHenry Alex Reese Denise Doring VanBuren Copyright ©2008 by the Hudson River Valley Institute Tel: 845-575-3052 Post: The Hudson River Valley Review Fax: 845-575-3176 c/o Hudson River Valley Institute E-mail: [email protected] Marist College, 3399 North Road, Web: www.hudsonrivervalley.org Poughkeepsie, NY 12601-1387 Subscription: The annual subscription rate is $20 a year (2 issues), $35 for two years (4 issues). -

The Second Edition

WASHINGTON STATE KNIGHTS OF COLUMBUS THE SECOND EDITION JANUARY 2015 Steve Snell - Editor - 509-386-3462 [email protected] THE SECOND EDITION IS A "Strong Visible Program" Time to start thinking! “Family of the Year" “Family Activity of the Year” Before the State Convention in Spokane this May. Grand Knights are urged to nominate an outstanding “Family of the Year” Nominations must be in my mailbox no later than April 1st to be considered for judging by the state officers For “Family Activity of the Year”, the same provisions apply, With the exception that the due date for those nominations to Be in my mailbox no later than April 15 STEVE SNELL, DDM, FDD, PFN, PGK, STATE FAMILY CHAIRMAN (509) 386-3462 - [email protected] ****************************************************************** The Knight of the Year Award The model Knight is difficult to describe. He may or may not be the one with the most abbreviations behind his name. He may or may not necessarily be the one with the longest list of achievements to his credit. He may be a quiet and humble man who seeks only to be the best Catholic he can be and who has dedicated him- self to the Church, the Order and his family. The Knight of the Year may be old or young, a relatively new knight or one who has served for fifty or more years. He is what best exemplifies what it means to be a Knight of Columbus. He is someone you are proud to call "Brother". All Knight of the Year submissions are to be received by the State Council Activities Director by April 1. -

Civilmentalhealth00riesrich.Pdf

# University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Francis Heisler and Friedy B. Heisler CIVIL LIBERTIES, MENTAL HEALTH, AND THE PURSUIT OF PEACE With Introductions by Julius Lucius Echeles Emma K. Albano Carl Tjerandsen An Interview Conducted by Suzanne B. Riess 1981-1983 Copyright 1983 by The Regents of the University of California ("a) All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the University of California and Francis Heisler and Friedy B. Heisler dated January 6, 1983. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the Regional Oral History Office, 486 Library, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The legal agreement with Francis Heisler and Friedy B. Heisler requires that they be notified of the request and allowed thirty days in which to respond. It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows: Francis Heisler and Friedy B. Heisler, "Civil Liberties, Mental Health, and the Pursuit of Peace," an oral history conducted 1981-1983 by Suzanne B. Riess, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1983. -

The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements

The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements By Laura K. Nelson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kim Voss, Chair Professor Raka Ray Professor Robin Einhorn Fall 2014 Copyright 2014 by Laura K. Nelson 1 Abstract The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements by Laura K. Nelson Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Berkeley Professor Kim Voss, Chair This dissertation challenges the widely accepted historical accounts of women's movements in the United States. Second-wave feminism, claim historians, was unique because of its development of radical feminism, defined by its insistence on changing consciousness, its focus on women being oppressed as a sex-class, and its efforts to emphasize the political nature of personal problems. I show that these features of second-wave radical feminism were not in fact unique but existed in almost identical forms during the first wave. Moreover, within each wave of feminism there were debates about the best way to fight women's oppression. As radical feminists were arguing that men as a sex-class oppress women as a sex-class, other feminists were claiming that the social system, not men, is to blame. This debate existed in both the first and second waves. Importantly, in both the first and the second wave there was a geographical dimension to these debates: women and organizations in Chicago argued that the social system was to blame while women and organizations in New York City argued that men were to blame. -

Horace L. Traubel And

DOCUMENT IRESUME ED 096 678 CS 201 570 AUTHOR Bussel, Alan TITLF In Defense of Freedom: Horace L. Traubel and the "Conservator." PUB DATE Aug 74 NOTE 23p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism (57th, San Diego, August 18-21, 1974) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.50 PLUS POSTAGE DESMIPTORS Academic Freedom; Civil Rights; *Freedom of Speech; Higher Education; *Journalism; *Newspapers; Periodicals; *Press Opinion; *Publishing Industry; Social Values IDBSTIFIERS Conservator; *Traubel (Horace L) ABSTRACT Philadelphia poet and journalist Horace L. Traubel's work as biographer of Walt Whitman has overshadowed his roleas crusading editor. Traubel (1858-1919) devoted 30years to publishing the "Conservator,' a monthly newspaper that reflected its editor's idiosyncratic philosophy and crusaded persistently for libertarian principles. He made the "Conservator" a champion of academic and artistic freedom and attacked those who sought to constrain liberties. Although the "Conservator" hada limited circulation, its readers--and Traubells followers--included a number of noteworthy individuals. Among them were Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs,soap magnate and reformer Joseph Fels, iconoclastic lecturer Robert G. Ingersoll, and William E. Walling, the reformer who helped foundthe National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.Traubel and the "Conservator" deserve recognition for their contributionsto the tradition of dissent in America. (Author/RB) U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION A WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ieDUCATION TNIS DOCUMENT NAS BEEN REPRO DUCED ExACTL Y AS RECEIvED &ROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN ATING IT POINTS O& v 1E* OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL iNSTiTUTE EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY In Defenseof Freedoms Horace L. -

CIVIL RIGHTS and SOCIAL JUSTICE Abolitionism: Activism to Abolish

CIVIL RIGHTS and SOCIAL JUSTICE Abolitionism: activism to abolish slavery (Madison Young Johnson Scrapbook, Chicago History Museum; Zebina Eastman Papers, Chicago History Museum) African Americans at the World's Columbian Exposition/World’s Fair of 1893 (James W. Ellsworth Papers, Chicago Public Library; World’s Columbian Exposition Photographs, Loyola University Chicago) American Indian Movement in Chicago Anti-Lynching: activism to end lynching (Ida B. Wells Papers, University of Chicago; Arthur W. Mitchell Papers, Chicago History Museum) Asian-American Hunger Strike at Northwestern U Ben Reitman: physician, activist, and socialist; founder of Hobo College (Ben Reitman Visual Materials, Chicago History Museum; Dill Pickle Club Records, Newberry Library) Black Codes: denied ante-bellum African-Americans living in Illinois full citizenship rights (Chicago History Museum; Platt R. Spencer Papers, Newberry Library) Cairo Civil Rights March: activism in southern Illinois for civil rights (Beatrice Stegeman Collection on Civil Rights in Southern Illinois, Southern Illinois University; Charles A. Hayes Papers, Chicago Public Library) Carlos Montezuma: Indian rights activist and physician (Carlos Montezuma Papers, Newberry Library) Charlemae Hill Rollins: advocate for multicultural children’s literature based at the George Cleveland Branch Library with Vivian Harsh (George Cleveland Hall Branch Archives, Chicago Public Library) Chicago Commission on Race Relations / The Negro in Chicago: investigative committee commissioned after the race riots -

INDIANA MAGAZINE of HISTORY Volume LIV SEPTEMBER 1958 NUMBER3

INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY Volume LIV SEPTEMBER 1958 NUMBER3 U..... U..... ...................................................................................... “Red Special”: Eugene V. Debs and the Campaign of 1908 H. Wayne Morgan* The days when American socialists counted their sym- pathizers in hundreds of thousands are gone, and many stu- dents and historians are unaware that fifty years ago the Socialist Party of America was a power to be reckoned with in presidential elections. The history books that extol the campaign exploits of William Jennings Bryan, Theodore Roosevelt, and Woodrow Wilson often fail to record that the most famous American socialist, Eugene Victor Debs, waged five presidential campaigns between 1900 and 1920. None of these campaigns was more colorful than that of 1908, the year of the “Red Special.” Preserved in song and poem, as well as in the fading memories of participants and bystanders, the Socialist party’s campaign of that year illustrated the vigor of the organization and the amount of effort which Socialists could pour into a national campaign. By 1908, the Socialist Party of America had made con- siderable progress toward fulfilling the promise it had shown in the presidential election of 1904. It could now claim its place as the third party of American politics, a position it had taken from the Prohibitionists in 1904. Politically, the Socialists were gaining strength on local levels. In Milwaukee, one of their strongholds, they had come close to capturing the mayor’s office in 1906 and had used their influence with * H. Wayne Morgan is John Randolph and Dora E. Haynes Fellow for 1958-1959 at the University of California at Los Angeles, where he has served as teaching assistant in the Department of History. -

Walt Whitman's Laws of Geographic Nomenclature

"Names are Magic": Walt Whitman's Laws of Geographic Nomenclature MICHAEL R. DRESSMAN THE LINES OF LEA VES of Grass are filled with names-names of races, occupations, individuals, trees, rivers, but especially places. Walt Whitman was passionately interested in American place-names, and he had some strong views on what kinds of names were appropriate for the America of which he sang. One could arrive at this conclusion induc- tively by analyzing the many poems of Leaves of Grass, and there have been some partial attempts to do this.1 On the other hand, it is possible to take a step behind the poems, "into the poet's mind," so to speak, to get a better idea of his theories on the use and value of names. This information on Whitman's principles of onomastics is abundant- ly available because the subject so thoroughly fascinated him. He has left many notebook entries and clippings attesting to his interest in language in general and names in particular. 2 The subject of place- names was frequently brought up in the conversations of his latter years, as recorded by his Boswell, Horace Traubel, in his volumes of With Walt Whitman in Camden.3 There is also evidence of Whitman's interest in names in his early journalism and in such later published essays as the posthumous An American Primer4 and "Slang in Amer- ica" which appeared first in the North American Review in November, 1885. Despite its title, "Slang in America" is almost wholly taken up with a discussion of names. In fact, early notes which he assembled apparently 1 See C.