Preliminary Socio-Economic Baseline Study Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sindh Flood 2011 - Union Council Ranking - Sanghar District

PAKISTAN - Sindh Flood 2011 - Union Council Ranking - Sanghar District Union council ranking exercise, coordinated by UNOCHA and UNDP, is a joint effort of Government and humanitarian partners Community Restoration Food Education in the notified districts of 2011 floods in Sindh. Its purpose is to: Identify high priority union councils with outstanding needs. SHAHEED SHAHEED SHAHEED BENAZIRABAD KHAIRPUR BENAZIRABAD KHAIRPUR BENAZIRABAD KHAIRPUR Facilitate stackholders to plan/support interventions and divert Shah Shah Shah Sikandarabad Sikandarabad Sikandarabad Paritamabad Paritamabad Paritamabad Gujri Gujri resources where they are most needed. Gul Gul Gujri Khadro Khadwari Khadro Khadwari Gul Khadro Khadwari Muhammad Muhammad Muhammad Laghari Laghari Laghari Shahpur Sanghar Shahpur Sanghar Shahpur Sanghar Serhari Chakar Kanhar Serhari Chakar Kanhar Provide common prioritization framework to clusters, agencies Shah Shah Serhari Chakar Kanhar Barhoon Barhoon Barhoon Shah Mardan Abad Mardan Abad Shahdadpur Mian Chutiaryoon Shahdadpur Mian Chutiaryoon Shahdadpur Mardan Abad Mian Chutiaryoon Asgharabad Jafar Sanghar 2 Asgharabad Jafar Sanghar 2 Asgharabad Jafar Sanghar 2 Khan Khan Lundo Soomar Sanghar 1 Lundo Soomar Sanghar 1 Lundo Soomar Khan Sanghar 1 and donors. Faqir HingoroLaghari Laghari Laghari Faqir Hingoro Faqir Hingoro Kurkali Kurkali Kurkali Jatia Jatia Jatia Maldasi Sinjhoro Bilawal Hingoro Maldasi Sinjhoro Bilawal Hingoro Maldasi Sinjhoro Bilawal Hingoro Manik Manik Manik Tahim Khipro Tahim Khipro First round of this exercise is completed from February - March Khori Khori Tahim Khipro Kumb Jan Nawaz Kumb Jan Nawaz Kumb Khori Pero Jan Nawaz DarhoonTando Ali DarhoonTando Pero Ali DarhoonTando Pero Ali Faqir Jan Nawaz Ali Faqir Jan Nawaz Ali Faqir Jan Nawaz Ali AdamShoro Hathungo AdamShoro Hathungo AdamShoro Hathungo Nauabad Nauabad Nauabad 2012. -

Caravan Report

1 | P a g e 2 | P a g e Background: If there is ever to be a Third World War, many believe it will be fought over water, with South Asia serving as the flashpoint. The region houses a quarter of the world’s population and has less than 5 percent of the global annual renewable water resources. Low water availability per person and high frequency of extreme weather events, including severe droughts, further increase the vulnerability of the area. Any disturbance by the country upstream is likely to impact life downstream. Also, as heightened interests to tame and exploit a river through dams, canals and hydel projects suggest, this region will be a zone of constant confrontations in the future. The vision 2025 of Pakistan clearly indicates that the existing flow of water of rivers will be diverted through building various mega schemes for water conservation for energy and agricultural purposes. Such decisions and policies based on vested political interests will further aggravate the socio-economic conditions of deltaic communities of the Sindh. A large water share of the River Indus is utilized by Punjab Province. Resultantly, the lower end of the River Indus that used to be known as “Mighty River Indus” has been reduced to the level of canal shows only tiny inconsistent storage of water. Such a massive destruction of the River Indus has led to the death of livelihood of the deltaic people. The Pakistan government has been planning to build more dams on Indus River. The PFF believes that the indigenous people along with the other natural habitat have the basic right to use the land and water first. -

Nutrition and Mortality Survey

NUTRITION AND MORTALITY SURVEY Tharparkar, Sanghar and Kamber Shahdadkhot districts of Sindh Province, Pakistan 18-25 March, 2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE OF CONTENT ................................................................................................................................... 2 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2. Objective of the Study ............................................................................................................................... 6 3. Methodology .............................................................................................................................................. 7 3.1 Study area ......................................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Study population .............................................................................................................................. 7 3.3 Study design ...................................................................................................................................... 8 3.3.1 Sample size -

Improving Decision-Making Systems for Decentralized Primary Education Delivery in Pakistan

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore Pardee RAND Graduate School View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the Pardee RAND Graduate School (PRGS) dissertation series. PRGS dissertations are produced by graduate fellows of the Pardee RAND Graduate School, the world’s leading producer of Ph.D.’s in policy analysis. The dissertation has been supervised, reviewed, and approved by the graduate fellow’s faculty committee. Improving Decision-making Systems for Decentralized Primary Education Delivery in Pakistan Mohammed Rehan Malik This document was submitted as a dissertation in July 2007 in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the doctoral degree in public policy analysis at the Pardee RAND Graduate School. -

Lakeside Energy (Pr Vate) Limited

BEFORE THE NATIONAL elECTRIC POWER REGULATORY AUTHORITY APPLICATION FOR GENERATION LICENCE IN RESPECT OF 50 MW WIND POWER PROJECT IN JHIMPIR, DISTRICT THATTA, PROVINCE OF SINDH, PAKISTAN Dated: 25.05.2017 Filed for and behalf of: LAKESIDE ENERGY (PR VATE) LIMITED Through: RIAA BARKER GILLETTE 68, NAZIMUDDIN ROAD, F-8/4, ISLAMABAD UAN: (051) 111-LAWYER WEBSITE: www.riaabarkergillette.com 31.05.2017 Registrar National Electric Power Regulatory Authority NEPRA Tower, Ataturk Avenue (East), Sector G-5/1 Islamabad, Pakistan. SUBJECT: APPLICATION FOR GRANT OF GENERATION LICENCE I, Brigadier (Retired) Tariq Izaz, Chief Operating Officer, being the duly authorized representative of Lakeside Energy {Private} Limited by virtue of a board resolution dated 15.01.2017, hereby to the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority {NEPRA} for the grant of a generation licence to pursuant to section 15 of the Regulation of Generation, Transmission and Distribution of Electric Power Act, 1997. I certify that the documents-in-support attached with this application are prepared and submitted in conformity with the provision of National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA) Licensing (Application and Modification Procedure) Regulations, 1999, and undertake to abide by the terms and provisions of above-said regulations. I further undertake and confirm that the information provided in the attached documents-in-support is true and corrected to the best of my knowledge and belief. A pay order in the sum of Rupees Three Hundred Thousand Three Thirty Six (PKR 300,336/-), being the non-refundable application processing fee calculated in accordance with Schedule-ll to National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Licensing (Application and Modification Procedure) Regulations, 1999, is also attached herewith. -

CWS-P/A Has Empowered Women in Thatta District with Skills, Basic Education, and Knowledge on Staying Safe

CWS-P/A has empowered women in Thatta District with skills, basic education, and knowledge on staying safe. Photo by Shahzad A. Fayyaz. FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION ONLY January - April 2014 Newsletter Volume 13, Issue 33 2014 Dear Readers, We welcome you to read CWS-P/A’s first newsletter for 2014. This January to April edition contains news about projects which continually impact the lives of communities in Pakistan and Afghanistan in positive ways. The projects include interventions in health and livelihoods for families in the districts of Kohat, Mansehra, Haripur, and Thatta in Pakistan. In Afghanistan, CWS-P/A continues to strengthen educational opportunities, especially for girls, by increasing awareness among parents and community members and by building the capacity of teachers. The newsletter also highlights work in Afghanistan toward improving health, especially for women and children. Additionally, read about the organization’s work for minorities and in raising awareness on the issues they face. There is further news about CWS-P/A’s work in promoting quality and accountability. This edition’s Hot Topic is about contingency planning for humanitarian organizations. We express our gratitude to you for taking the time to read our newsletter. You may send feedback and In This Edition suggestions to [email protected] The CWS - P/A team Quality and Accountability In this Edition 02 for Project Cycle Management Suggested Reading 02 – A Pocket Booklet for Field Mission Statement 02 Practitioners News from CWS-P/A 03 Vocational Training Inspires Young Afghan Men and Women 10 Implementing Education with Sports and Play 12 Guldasta’s Story: Helping Women Regain Good Health 14 Words of Wisdom 16 Hot Topic 16 Suggested Reading By: Sylvie Robert and Astrid de Valon Table of Contents Table The first edition of the Quality and Accountability for Project Cycle Management booklet is a CWS–P/A as an ecumenical organization user-friendly guide to the various quality will struggle for a community based and accountability tools and standards. -

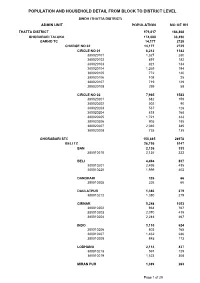

Population and Household Detail from Block to District Level

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (THATTA DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH THATTA DISTRICT 979,817 184,868 GHORABARI TALUKA 174,088 33,450 GARHO TC 14,177 2725 CHARGE NO 02 14,177 2725 CIRCLE NO 01 6,212 1142 380020101 1,327 280 380020102 897 182 380020103 821 134 380020104 1,269 194 380020105 772 140 380020106 108 25 380020107 719 129 380020108 299 58 CIRCLE NO 02 7,965 1583 380020201 682 159 380020202 502 90 380020203 537 128 380020204 818 168 380020205 1,721 333 380020206 905 185 380020207 2,065 385 380020208 735 135 GHORABARI STC 150,885 28978 BELI TC 26,756 5147 BAN 2,136 333 380010210 2,136 333 BELI 4,494 837 380010201 2,495 435 380010220 1,999 402 DANDHARI 326 66 380010205 326 66 DAULATPUR 1,380 279 380010212 1,380 279 GIRNAR 5,248 1053 380010202 934 167 380010203 2,070 419 380010204 2,244 467 INDO 3,110 624 380010206 803 165 380010207 1,462 286 380010208 845 173 LODHANO 2,114 437 380010218 591 129 380010219 1,523 308 MIRAN PUR 1,389 263 Page 1 of 29 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (THATTA DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 380010213 529 102 380010214 860 161 SHAHPUR 3,016 548 380010215 1,300 243 380010216 901 160 380010221 815 145 SUKHPUR 1,453 275 380010209 1,453 275 TAKRO 668 136 380010217 668 136 VIKAR 1,422 296 380010211 1,422 296 GARHO TC 22,344 4350 ADANO 400 80 380010113 400 80 GAMBWAH 440 58 380010110 440 58 GUBA WEST 509 105 380010126 509 105 JARYOON 366 107 380010109 366 107 JHORE PATAR 6,123 1143 380010118 504 98 380010119 1,222 231 380010120 -

The Land of Five Rivers and Sindh by David Ross

THE LAND OFOFOF THE FIVE RIVERS AND SINDH. BY DAVID ROSS, C.I.E., F.R.G.S. London 1883 Reproduced by: Sani Hussain Panhwar The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE MOST HONORABLE GEORGE FREDERICK SAMUEL MARQUIS OF RIPON, K.G., P.C., G.M.S.I., G.M.I.E., VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, THESE SKETCHES OF THE PUNJAB AND SINDH ARE With His Excellency’s Most Gracious Permission DEDICATED. The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 PREFACE. My object in publishing these “Sketches” is to furnish travelers passing through Sindh and the Punjab with a short historical and descriptive account of the country and places of interest between Karachi, Multan, Lahore, Peshawar, and Delhi. I mainly confine my remarks to the more prominent cities and towns adjoining the railway system. Objects of antiquarian interest and the principal arts and manufactures in the different localities are briefly noticed. I have alluded to the independent adjoining States, and I have added outlines of the routes to Kashmir, the various hill sanitaria, and of the marches which may be made in the interior of the Western Himalayas. In order to give a distinct and definite idea as to the situation of the different localities mentioned, their position with reference to the various railway stations is given as far as possible. The names of the railway stations and principal places described head each article or paragraph, and in the margin are shown the minor places or objects of interest in the vicinity. -

Parcel Post Compendium Online Pakistan Post PKA PK

Parcel Post Compendium Online PK - Pakistan Pakistan Post PKA Basic Services CARDIT Carrier documents international Yes transport – origin post 1 Maximum weight limit admitted RESDIT Response to a CARDIT – destination Yes 1.1 Surface parcels (kg) 50 post 1.2 Air (or priority) parcels (kg) 50 6 Home delivery 2 Maximum size admitted 6.1 Initial delivery attempt at physical Yes delivery of parcels to addressee 2.1 Surface parcels 6.2 If initial delivery attempt unsuccessful, Yes 2.1.1 2m x 2m x 2m No card left for addressee (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 6.3 Addressee has option of paying taxes or Yes 2.1.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Yes duties and taking physical delivery of the (or 3m length & greatest circumference) item 2.1.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m No 6.4 There are governmental or legally (or 2m length & greatest circumference) binding restrictions mean that there are certain limitations in implementing home 2.2 Air parcels delivery. 2.2.1 2m x 2m x 2m No 6.5 Nature of this governmental or legally (or 3m length & greatest circumference) binding restriction. 2.2.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Yes (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 2.2.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m No 7 Signature of acceptance (or 2m length & greatest circumference) 7.1 When a parcel is delivered or handed over Supplementary services 7.1.1 a signature of acceptance is obtained Yes 3 Cumbersome parcels admitted No 7.1.2 captured data from an identity card are Yes registered 7.1.3 another form of evidence of receipt is No Parcels service features obtained 5 Electronic exchange of information -

Development of High Speed Rail in Pakistan

TSC-MT 11-014 Development of High Speed Rail in Pakistan Stockholm, June 2011 Master Thesis Abdul Majeed Baloch KTH |Development of High Speed Rail In Pakistan 2 Foreword I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors, Anders Lindahl, Bo-Lennart Nelldal & Oskar Fröidh for their encouragement, patience, help, support at different stages & excellent guidance with Administration, unique ideas, feedback etc. Above all I would like to thank my beloved parents ’Shazia Hassan & Dr. Ali Hassan’ , my brothers, sisters from soul of my heart, for encouragement & support to me through my stay in Sweden, I wish to say my thanks to all my friends specially ‘ Christina Nilsson’ for her encouragement, and my Landlord ‘Mikeal & Ingmarie’ in Sweden . Finally I would like to say bundle of thanks from core of my Heart to KTH , who has given me a chance for higher education & all people who has been involved directly or in-directly with completion of my thesis work Stockholm, June 2011 Abdul Majeed Baloch [email protected] KTH |Development of High Speed Rail In Pakistan 3 KTH |Development of High Speed Rail In Pakistan 4 Summary Passenger Railway service are one of the key part of the Pakistan Railway system. Pakistan Railway has spent handsome amount of money on the Railway infrastructure, but unfortunately tracks could not be fully utilized. Since last many years due to the fall of the Pakistan railway, road transport has taken an advantage of this & promised to revenge. Finally road transport has increased progressive amount of share in his account. In order to get the share back, in 2006 Pakistan Railway decided to introduce High speed train between Rawalpindi-Lahore 1.According Pakistan Railway year book 2010, feasibility report for the high speed train between Rawalpindi-Lahore has been completed. -

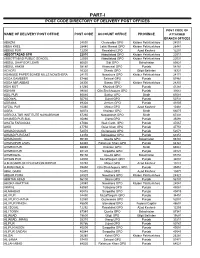

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

1951-81 Population Administrative . Units

1951- 81 POPULATION OF ADMINISTRATIVE . UNITS (AS ON 4th FEBRUARY. 1986 ) - POPULATION CENSUS ORGANISATION ST ATIS TICS DIVISION GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN PREFACE The census data is presented in publica tions of each census according to the boundaries of districts, sub-divisions and tehsils/talukas at the t ime of the respective census. But when the data over a period of time is to be examined and analysed it requires to be adjusted fo r the present boundaries, in case of changes in these. It ha s been observed that over the period of last censuses there have been certain c hanges in the boundaries of so me administrative units. It was, therefore, considered advisable that the ce nsus data may be presented according to the boundary position of these areas of some recent date. The census data of all the four censuses of Pakistan have, therefore, been adjusted according to the administ rative units as on 4th February, 1986. The details of these changes have been given at Annexu re- A. Though it would have been preferable to tabulate the whole census data, i.e., population by age , sex, etc., accordingly, yet in view of the very huge work involved even for the 1981 Census and in the absence of availability of source data from the previous three ce nsuses, only population figures have been adjusted. 2. The population of some of the district s and tehsils could no t be worked out clue to non-availability of comparable data of mauzas/dehs/villages comprising these areas. Consequently, their population has been shown against t he district out of which new districts or rehsils were created.