Russell's Platonism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What to Be Realist About in Linguistic Science

What to be realist about in linguistic science Geoffrey K. Pullum School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences University of Edinburgh This paper was presented at a workshop entitled ‘Foundation of Linguistics: Languages as Abstract Objects’ at the Technische Universitat¨ Carolo-Wilhelmina in Braunschweig, Germany, June 25–28. At the end of his viva, Hilary Putnam asked him, “And tell us, Mr. Boolos, what does the analytical hierarchy have to do with the real world?” Without hesitating Boolos replied, “It’s part of it.” [From the Wikipedia article on the MIT logician George Boolos] Prefatory remarks on realism I need to begin by clarifying what is meant (or at least, what I and others have meant) by ‘realism’. That such clarification is necessary is indicated by the fact that the subtitle of this workshop (‘Lan- guages as Abstract Objects’) clearly pays homage to Katz (1981) (Language and Other Abstract Objects). What the late Jerrold J. Katz meant by the word ‘realism’ does not comport with the usage of most philosophers. Katz shows little interest in defining his terms. He barely even waves a hand in that direc- tion. The third page of Language and Other Abstract Objects book announces that he has had an epiphany: there is “an alternative to both the American structuralists’ and the Chomskian concep- tion of what grammars are theories of, namely, the Platonic realist view that grammars are theories of abstract objects (sentences)” (Katz 1981, 3). Neither ‘Platonic’ nor ‘realist’ are analysed, expli- cated, or even glossed at this point. ‘Platonic realism’ is thereafter abbreviated to ‘Platonism’ and simply assumed to be understood. -

On Moral Understanding

COMMENTTHE COLLEGE NEWSLETTER ISSUE NO 147 | MAY 2003 TOM WHIPPS On Moral Understanding DNA pioneers: The surviving members of the King’s team, who worked on the discovery of the structure of DNA 50 years ago, withDavid James Watson, K Levytheir Cambridge ‘rival’ at the time. From left Ray Gosling, Herbert Wilson, DNA at King’s: DepartmentJames Watson and of Maurice Philosophy Wilkins King’s College the continuing story University of London Prize for his contribution – and A day of celebrations their teams, but also to subse- quent generations of scientists at ver 600 guests attended a cant scientific discovery of the King’s. unique day of events celeb- 20th century,’ in the words of Four Nobel Laureates – Mau- Orating King’s role in the 50th Principal Professor Arthur Lucas, rice Wilkins, James Watson, Sid- anniversary of the discovery of the ‘and their research changed ney Altman and Tim Hunt – double helix structure of DNA on the world’. attended the event which was so 22 April. The day paid tribute not only to oversubscribed that the proceed- Scientists at King’s played a King’s DNA pioneers Rosalind ings were relayed by video link to fundamental role in this momen- Franklin and Maurice Wilkins – tous discovery – ‘the most signifi- who went onto win the Nobel continued on page 2 2 Funding news | 3 Peace Operations Review | 5 Widening participation | 8 25 years of Anglo-French law | 11 Margaret Atwood at King’s | 12 Susan Gibson wins Rosalind Franklin Award | 15 Focus: School of Law | 16 Research news | 18 Books | 19 KCLSU election results | 20 Arts abcdef U N I V E R S I T Y O F L O N D O N A C C O M M O D A T I O N O F F I C E ACCOMMODATION INFORMATION - FINDING SOMEWHERE TO LIVE IN THE PRIVATE SECTOR Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy WARNING: Under no circumstances inshould the this University document be of taken London as providing legal advice. -

Socrates, Phil Inquiry & the Elenctic Method (F11new)

PLATO, PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY & THE ELENCTIC METHOD All human beings, by their nature, desire understanding. — Aristotle, Metaphysics (Book 1) The safest general characterisation of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato. — Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality The elenctic method (part 1): on Meno’s enumerative THE BIG IDEAS TO MASTER definition of (human) virtue • Theory • Socratic humility On Platonic realism & Socratic definitions. According to Plato, a • The elenctic method central part of philosophical inquiry involves an attempt to • Platonic realism understand the Forms. This implies that he is committed the view • Platonic Forms we will call Platonic realism, namely, the view that • Socratic definitions • Essences Platonic realism. The Forms exist. • Natural kinds vs. artefacts • Abstract vs. concrete entities So, according to this theory, Reality contains the Forms. But what • Essential vs. accidental properties are the Forms? That question is best answered as follows. Much of • Counterexample the most important research that philosophers and other scholars do • Reductio ad absurdum argument involves an attempt to answer questions of the form ‘what is x?’ • Sound argument Physicists, for instance, ask ‘what is a black hole?’; biologists ask • Valid argument ‘what is an organism?’; mathematicians ask ‘what is a right triangle?’ • The correspondence theory of truth Let us call the correct answer to a what-is-x question the Socratic • Fact definition of x. We can say, then, that physicists are seeking the Socratic definition of a black hole, biologists investigate the Socratic definition of an organism, and mathematicians look to determine the Socratic definition of a right triangle. -

CHAPTER 1 and Unexemplified Properties, Kinds, and Relations

UNIVERSALS I: METAPHYSICAL REALISM existing objects; whereas other realists believe that there are both exemplified CHAPTER 1 and unexemplified properties, kinds, and relations. The problem of universals I Realism and nominalism The objects we talk and think about can be classified in all kinds of Metaphysical realism ways. We sort things by color, and we have red things, yellow things, and blue things. We sort them by shape, and we have triangular things, circular things, and square things. We sort them by kind, and 0 Realism and nominalism we have elephants, oak trees, and paramecia. The kind of classification The ontology of metaphysical realism at work in these cases is an essential component in our experience of the Realism and predication world. There is little, if anything, that we can think or say, little, if anything, that counts as experience, that does not involve groupings of Realism and abstract reference these kinds. Although almost everyone will concede that some of our 0 Restrictions on realism - exemplification ways of classifying objects reflect our interests, goals, and values, few 0 Further restrictions - defined and undefined predicates will deny that many of our ways of sorting things are fixed by the 0 Are there any unexemplified attributes? objects themselves.' It is not as if we just arbitrarily choose to call some things triangular, others circular, and still others square; they are tri- angular, circular, and square. Likewise, it is not a mere consequence of Overview human thought or language that there are elephants, oak trees, and paramecia. They come that way, and our language and thought reflect The phenomenon of similarity or attribute agreement gives rise to the debate these antecedently given facts about them. -

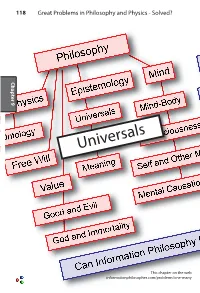

Universals.Pdf

118 Great Problems in Philosophy and Physics - Solved? Chapter 9 Chapter Universals This chapter on the web informationphilosopher.com/problems/one-many Universals 119 Universals A “universal” in metaphysics is a property or attribute that is shared by many particular objects (or concepts). It has a subtle relationship to the problem of the one and the many. It is also the question of ontology.1 What exists in the world? Ontology is intimately connected with epistemology - how can we know what exists in the world? Knowledge about objects consists in describing the objects with properties and attributes, including their relations to other objects. Rarely are individual properties unique to an individual object. Although a “bundle of properties” may uniquely charac- 9 Chapter terize a particular individual, most properties are shared with many individuals. The “problem of universals” is the existential status of a given shared property. Does the one universal property exist apart from the many instances in particular objects? Plato thought it does. Aristotle thought it does not. Consider the property having the color red. Is there an abstract concept of redness or “being red?” Granted the idea of a concept of redness, in what way and where in particular does it exist? Nomi- nalists (sometimes called anti-realists) say that it exists only in the particular instances, and that redness is the name of this property. Conceptualists say that the concept of redness exists only in the minds of those persons who have grasped the concept of redness. They might exclude color-blind persons who cannot perceive red. -

1. Armstrong and Aristotle There Are Two Main Reasons for Not

RECENSIONI&REPORTS report ANNABELLA D’ATRI DAVID MALET ARMSTRONG’S NEO‐ARISTOTELIANISM 1. Armstrong and Aristotle 2. Lowe on Aristotelian substance 3. Armstrong and Lowe on the laws of nature 4. Conclusion ABSTRACT: The aim of this paper is to establish criteria for designating the Systematic Metaphysics of Australian philosopher David Malet Armstrong as neo‐ Aristotelian and to distinguish this form of weak neo‐ Aristotelianism from other forms, specifically from John Lowe’s strong neo‐Aristotelianism. In order to compare the two forms, I will focus on the Aristotelian category of substance, and on the dissimilar attitudes of Armstrong and Lowe with regard to this category. Finally, I will test the impact of the two different metaphysics on the ontological explanation of laws of nature. 1. Armstrong and Aristotle There are two main reasons for not considering Armstrong’s Systematic Metaphysics as Aristotelian: a) the first is a “philological” reason: we don’t have evidence of Armstrong reading and analyzing Aristotle’s main works. On the contrary, we have evidence of Armstrong’s acknowledgments to Peter Anstey1 for drawing his attention to the reference of Aristotle’s theory of truthmaker in Categories and to Jim Franklin2 for a passage in Aristotle’s Metaphysics on the theory of the “one”; b) the second reason is “historiographic”: Armstrong isn’t listed among the authors labeled as contemporary Aristotelian metaphysicians3. Nonetheless, there are also reasons for speaking of Armstrong’s Aristotelianism if, according to 1 D. M. Armstrong, A World of State of Affairs, Cambridge University Press, New York 1978, p. 13. 2 Ibid., p. -

Causation: a Realist Approach by MICHAEL TOOLEY Oxford University Press, 1988

the chief editor with a historical survey of various views of the nature of philosophy and concludes with a short glossary of philosophical terms and a chronological table of memorable dates in philosophy and other arts and sciences from 1600 to 1960. The various chapters, with few exceptions, show a consistent fluency, clarity and readability. They are, in the main, conventional, orthodox, traditional, neutral, impartial, fair and safe, though, naturally, the expert reader will have disagreements with specific points. Usually a clear distinction is made, where appropriate, between analytic and normative considerations of the topic and something is said on each. There is only a little overlap between chapters. The title is misleading. Innumerable topics are not discussed at all. No essay is devoted to any philosopher, major or minor, as such, though frequent references are made to many in passing, since, in fact, the vast majority of the chapters consist of semi-historical, semi-critical surveys of the standard views on the topic under consideration. This fault might be remedied by using the book in conjunction with the well known Critical History of Western Philosophy edited by O’Connor. The book lacks the vast range of Edwards’ Encyclopaedia ofPhilosophy; and, though each chapter is usually longer and more widely cast than most of his entries, the total is far less comprehensive. Just because each chapter tries to cover too much ground in too wide a sweep, I doubt it will be very intelligible as a reference book to the class of reader - “the general reader . the sixth former . university students ofphilosophy . -

Download Download

rticles AXIOM OF INFINITY AND PLATO’S THIRD MAN Dale Jacquette Philosophy / U. of Bern Bern, be ch-3000, Switzerland [email protected] As a contribution to the critical appreciation of a central thesis in Russell’s philo- sophical logic, I consider the Third Man objection to Platonic realism in the philosophy of mathematics, and argue that the Third Man inWnite regress, for those who accept its assumptions, provides a worthy substitute for Whitehead and Russell’s Axiom of InWnity in positing a denumerably inWnite set or series onto which other sets, series, and formal operations in the foundations of math- ematics can be mapped. i he Third Man objection to Plato’s theory of Forms is sometimes oTered as an embarrassment to Platonic realism in the philoso- Tphy of mathematics. I argue here that, far from constituting a liability to Platonic realism, the Third Man regress can be turned to real- ism’s advantage by providing the basis for a proof justifying the existence of an inWnite set, eTectively replacing the need to stipulate or posit by Wat a logically unsupported Axiom of InWnity for the foundations of mathe- matics, as in A.yN. Whitehead and Bertrand Russell’s Principia Mathe- matica. 2 One way to formulate the Third Man objection to Plato’s theory of Forms is to consider the full implications of the following principles: russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies n.s. 30 (summer 2010): 5–13 The Bertrand Russell Research Centre, McMaster U. issn 0036-01631; online 1913-8032 C:\Users\Milt\Desktop\backup pm) 24, 2010 (10:17 September copy of Ken's G\WPData\TYPE3001\russell 30,1 032 red corrected.wpd 6 dale jacquette form1wFor any individual xz and any property F, Fxz if and only if there exists an abstract archetypal Platonic Form fz, by virtue of which xz as an instance of fz has property Fzz; alternatively, we can also say that a term designating Form fz grammatically nominalizes the meaning or content of corresponding property F. -

Nominalism - New World Encyclopedia

Nominalism - New World Encyclopedia http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Nominalism Nominalism From New World Encyclopedia Previous (Nomad) Next (Non-cognitivism) Nominalism is the philosophical view that abstract concepts, general terms, or universals have no independent existence but exist only as names. It also claims that various individual objects labeled by the same term have nothing in common but their name. In this view, it is only actual physical particulars that can be said to be real, and universals exist only post res, that is, subsequent to particular things. Nominalism is best understood in contrast to philosophical or ontological realism. Philosophical realism holds that when people use general terms such as "cat" or "green," those universals really exist in some sense of "exist," either independently of the world in an abstract realm (as was held by Plato, for instance, in his theory of forms) or as part of the real existence of individual things in some way (as in Aristotle's theory of hylomorphism ). The Aristotelian type of realism is usually called moderate realism. As a still another alternative, there is a school called conceptualism, which holds that universals are just concepts in the mind. In the Middle Ages, there was a heated realist-nominalist controversy over universals. History shows that after the Middle Ages, nominalism became more popularly accepted than realism. It is basically with the spirit of nominalism that empiricism, pragmatism, logical positivism, and other modern schools have been developed. But, this does not mean that any really satisfactory solution to the controversy has been found. So, even nominalism has developed more moderate versions such as "resemblance" nominalism and "trope" nominalism. -

The Problem of Universals from Antiquity to the Middle Ages

The Problem of Universals from Antiquity to the Middle Ages https://www.ontology.co/universals-history.htm Theory and History of Ontology by Raul Corazzon | e-mail: [email protected] The Problem of Universals in Antiquity and Middle Ages INTRODUCTION "One of the most debated problems during the Middle Ages was the problem of the nature of general concepts. Greek logic, after long discussions, established the theory of the concept, which became classic, and was transmitted by commentators in their manuals and compendia. In the Middle Ages, the problem of the nature of general concepts, called by the logicians of the time universalia, was placed in the centre of logical and philosophical concerns, and gave rise to the famous "dispute of the universals". (...) This dispute lasted throughout the Middle Ages, though in certain periods a particular conception might prevail. This problem originates from a famous passage in Porphyry's Introduction to Aristotle's Categories -- Isagogé -- translated by Boethius, a treatise which represented the corner- stone of all dialectical studies. This passage appears at the beginning of the above mentioned work and it raised the following problem: are genera and species real, or are they empty inventions of the intellect? Here is that famous passage, opening the Prooemium in Porphyry's Isagogé: De generibus speciebus illud quidem sive subsistent, sine in nudis intellectibus posita sunt, sive subsistentia corporalia sent an incorporalia, et utrum separata a sensibilibus an in sensibilibus posita et circa ea constantia, dicere recusabo; altissimum mysterium est hujus modi et majoris indigens inquisitionis ("I shall avoid investigating whether genera and species do exist in themselves, or as mere notions of the intellect, or whether they have a corporeal, or incorporeal existence, or whether they have an existence separated from sensible things, or only in sensible things; it is quite a mystery which requires a more thorough investigation than the present one"). -

Empiricism, Semantics, and Ontology

Empiricism, Semantics, and Ontology Rudolf Carnap Revue Internationale de Philosophie 4 (1950): 20-40. Reprinted in the Supplement to Meaning and Necessity: A Study in Semantics and Modal Logic, enlarged edition (University of Chicago Press, 1956). 1. The problem of abstract entities Empiricists are in general rather suspicious with respect to any kind of abstract entities like properties, classes, relations, numbers, propositions, etc. They usually feel much more in sympathy with nominalists than with realists (in the medieval sense). As far as possible they try to avoid any reference to abstract entities and to restrict themselves to what is sometimes called a nominalistic language, i.e., one not containing such references. However, within certain scientific contexts it seems hardly possible to avoid them. In the case of mathematics some empiricists try to find a way out by treating the whole of mathematics as a mere calculus, a formal system for which no interpretation is given, or can be given. Accordingly, the mathematician is said to speak not about numbers, functions and infinite classes but merely about meaningless symbols and formulas manipulated according to given formal rules. In physics it is more difficult to shun the suspected entities because the language of physics serves for the communication of reports and predictions and hence cannot be taken as a mere calculus. A physicist who is suspicious of abstract entities may perhaps try to declare a certain part of the language of physics as uninterpreted and uninterpretable, that part which refers to real numbers as space-time coordinates or as values of physical magnitudes, to functions, limits, etc. -

Táborite Apocalyptic Violence and Its Intellectual Inspirations (1410-1415) Martin Pjecha

Táborite Apocalyptic Violence and its Intellectual Inspirations (1410-1415) Martin Pjecha To cite this version: Martin Pjecha. Táborite Apocalyptic Violence and its Intellectual Inspirations (1410-1415). Bohemian Reformation and Religious Practice, Institute of philosophy, Czech Academy of Sciences (Prague), 2018, 11, pp.76-97. halshs-02430698 HAL Id: halshs-02430698 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02430698 Submitted on 7 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial| 4.0 International License Táborite Apocalyptic Violence and its Intellectual Inspirations (1410–1415)1 Martin Pjecha (Prague) Research on the origins of Táborite violence is certainly not a new field with- in Hussite historiography, even if the topic has not attracted much attention in recent decades. Among those contributing factors explored by historians, we find intellectual influences from pre-Hussite heterodox thinkers and com- munities, socio-economic transformations on local and regional levels, and socio-political developments within Bohemia and in Church relations. Less emphasised, however, are intellectual continuities from within the Hussite reform movement which could have helped form the opinions of the Táborite priests on violence.