Graham Greene's Narrative in Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pax Ecclesia: Globalization and Catholic Literary Modernism

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2011 Pax Ecclesia: Globalization and Catholic Literary Modernism Christopher Wachal Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Wachal, Christopher, "Pax Ecclesia: Globalization and Catholic Literary Modernism" (2011). Dissertations. 181. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2011 Christopher Wachal LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO PAX ECCLESIA: GLOBALIZATION AND CATHOLIC LITERARY MODERNISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN ENGLISH BY CHRISTOPHER B. WACHAL CHICAGO, IL MAY 2011 Copyright by Christopher B. Wachal, 2011 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Nothing big worth undertaking is undertaken alone. It would certainly be dishonest for me to claim that the intellectual journey of which this text is the fruition has been propelled forward solely by my own energy and momentum. There have been many who have contributed to its completion – too many, perhaps, to be done justice in so short a space as this. Nonetheless, I would like to extend my sincere thanks to some of those whose assistance I most appreciate. My dissertation director, Fr. Mark Bosco, has been both a guide and an inspiration throughout my time at Loyola University Chicago. -

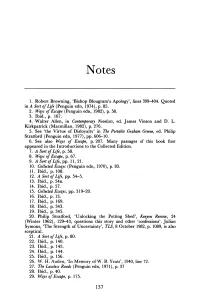

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

Norman Macleod

Norman Macleod "This strange, rather sad story": The Reflexive Design of Graham Greene's The Third Man. The circumstances surrounding the genesis and composition of Gra ham Greene's The Third Man ( 1950) have recently been recalled by Judy Adamson and Philip Stratford, in an essay1 largely devoted to characterizing some quite unwarranted editorial emendations which differentiate the earliest American editions from British (and other textually sound) versions of The Third Man. It turns out that these are changes which had the effect of giving the American reader a text which (for whatever reasons, possibly political) presented the Ameri can and Russian occupation forces in Vienna, and the central charac ter of Harry Lime, and his dishonourable deeds and connections, in a blander, softer light than Greene could ever have intended; indeed, according to Adamson and Stratford, Greene did not "know of the extensive changes made to his story in the American book and now claims to be 'horrified' by them"2 • Such obscurely purposeful editorial meddlings are perhaps the kind of thing that the textual and creative history of The Third Man could have led us to expect: they can be placed alongside other more official changes (usually introduced with Greene's approval and frequently of his own doing) which befell the original tale in its transposition from idea-resuscitated-from-old notebook to story to treatment to script to finished film. Adamson and Stratford show that these approved and 'official' changes involved revisions both of dramatis personae and of plot, and that they were often introduced for good artistic or practical reasons. -

Nesetrilovai Reflection1930s O

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Reflection of the 1930´s British Society in Graham Greene´s Brighton Rock Iva Nešetřilová Bachelor thesis 2017 Prohlašuji: Tuto práci jsem vypracovala samostatně. Veškeré literární prameny a informace, které jsem v práci využila, jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. Byla jsem seznámena s tím, že se na moji práci vztahují práva a povinnosti vyplývající ze zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., autorský zákon, zejména se skutečností, že Univerzita Pardubice má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití této práce jako školního díla podle § 60 odst. 1 autorského zákona, a s tím, že pokud dojde k užití této práce mnou nebo bude poskytnuta licence o užití jinému subjektu, je Univerzita Pardubice oprávněna ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, které na vytvoření díla vynaložila, a to podle okolností až do jejich skutečné výše. Souhlasím s prezenčním zpřístupněním své práce v Univerzitní knihovně. V Pardubicích dne 17.3.2017 Iva Nešetřilová Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Olga Roebuck, M.Litt. Ph.D. for giving me the opportunity to choose this topic, for her professional help, advice, and, especially, for the time she had spent when consulting my work. Annotation This paper examines and analyses the reflection of British Society in the novel Brighton Rock by Graham Green. The first part explores the situation in Britain around the 1930s, the period when the book was written and published, and briefly focuses on the changing landscape brought about by the Depression and aftermath of the First World War. The emphasis is confined mostly to how these changes affected the lower classes, and a brief description of what constitutes working class is provided. -

The Lawless Roads

The Lawless Roads The Lawless Roads. Graham Greene. 1409020517, 9781409020516. Random House, 2010. 2010. 240 pages In 1938 Graham Greene was commissioned to visit Mexico to discover the state of the country and its people in the aftermath of the brutal anti-clerical purges of President Calles. His journey took him through the tropical states of Chiapas and Tabasco, where all the churches had been destroyed or closed and the priests driven out or shot. The experiences were the inspiration for his acclaimed novel, The Power and the Glory. Pdf Download http://variationid.org/.InmBGHm.pdf The Power And The Glory. ISBN:9781409017431. 240 pages. During a vicious persecution of the clergy in Mexico, a worldly priest, the 'whisky priest', is on the run. With the police closing in, his routes of escape are being shut off. Oct 2, 2010. Fiction. Graham Greene Twenty-One Stories Travel journey Without Maps The Lawless Roads In Search of a Character Getting to Know the General Essays Collected Essays First published in Great Britain in 1969 by The Bodley Head Vintage Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London SW1V. The long and frequently quoted passage from Cardinal Newman which forms the motto to The Lawless Roads (the quarry for The Power and the Glory) makes the general point most clearly, ending: Greene gives the personal application on the third page of The Lawless Roads:. Abstract Assassination plots that have been devised against Catholic bishop Don Samuel Ruiz Garcia are discussed, and Ruiz Garcia is profiled. Ruiz Garcia has worked tirelessly in Mexico to promote human rights but has been asked by the Vatican to" retire" because. -

Moral Values in Espionage Novels by Graham Greene

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Viktoria Fedorova Moral Values In Espionage Novels by Graham Greene Bachelor's Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. 2017 / declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. Viktória Fedorová 2 Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, Stephen Paul Hardy, PhD. for all his valuable advice. I would also like to thank my family, my partner and my friends for their support. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 5 2. Graham Greene: Life and Vision 10 2.1. Espionage 15 2.2. Greene and Catholicism 17 2.3. The Entertainments and "Serious Novels" 21 3. The Ministry of Fear 23 4. The Quiet American 32 5. The Comedians 46 6. Conclusion °1 7. Works Cited 65 8. Resume (English) 67 9. Resume (Czech) 68 4 1. Introduction The aim of this thesis is to analyse and compare the treatment of moral values in three espionage novels by Graham Greene- The Ministry of Fear, The Quiet American and The Comedians- to show that the debate of moral values in Greene's novels is closely connected with the notion that the gravity of sins committed is connected to the amount of pain one's decision causes to other human beings. The evil committed by his characters is to be judged individually and one of his characters' greatest fears is the fear to cause the pain to other human beings. Espionage novels were used because Greene's experience with espionage is often projected into his novels and it is often central to the plot. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

Wireless Women: the “Mass” Retreat of Brighton Rock Jeffrey Sconce Northwestern University

47 Wireless Women: The “Mass” Retreat of Brighton Rock Jeffrey Sconce Northwestern University All popular fi ction must feature a romantic couple, and so it is in the open- ing pages of Brighton Rock (1938) that Graham Greene introduces Pinkie and Rose, the teenagers whose abrasive courtship and perverse marriage will both enact and travesty this convention as the novel unfolds. When Pinkie fi rst meets Rose, she is working at Snow’s as a waitress. Entering the establishment, Pinkie encounters a wireless set “droning a programme of weary music broadcast by a cinema organist—a great vox humana trembl[ing] across the crumby stained desert of used cloths: the world’s wet mouth lamenting over life” (24). This reference to the weary lamentations of wireless remains an isolated detail until moments before Pinkie takes his fatal plunge over the cliff in the novel’s closing pages. Having taken Rose up the coast from Brighton with plans to facilitate her suicide, the couple sits for a few awkward moments in an empty hotel lounge. As Rose works on her half of the couple’s double-suicide note, to be left behind for the benefi t of “Daily Express readers, to what one called the world” (260), wireless makes a brief but meaningful re-appearance as that world speaks back. “The wireless was hidden behind a potted plant; a violin came wailing out, the notes shaken by atmospherics,” writes Greene (250). Later, the violin fades away and “a time signal pinged through the rain. A voice behind the plant gave them the weather report—storms coming up from the Continent, a depression in the Atlantic, tomorrow’s forecast” (251). -

"Freedom and Alienation in Graham Greene's "Brighton Rock," Albert Camus' "The Plague," and Other Related Texts."

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses "Freedom and alienation in Graham Greene's "Brighton Rock," Albert Camus' "The Plague," and other related texts." Breeze, Brian How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Breeze, Brian (2005) "Freedom and alienation in Graham Greene's "Brighton Rock," Albert Camus' "The Plague," and other related texts.". thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42557 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ FREEDOM AND ALIENATION in Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock, Albert Camus’ The Plague, and other related texts. BRIAN BREEZE M.Phil. 2005 UNIVERSITY OF WALES SWANSEA PRIFYSGOL CYMRU ABERTAWE ProQuest N um ber: 10805306 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Graham Greene and Mexico ~ a Hint of an Explanation

Graham Greene And Mexico ~ A Hint Of An Explanation Graham Greene 1904 – 1991 In a short letter to the press, in which he referred to Mexico, Graham Greene substantially expressed his view of the world. “I must thank Mr. Richard West for his understanding notice ofThe Quiet American. No critic before, that I can remember, has thus pinpointed my abhorrence of the American liberal conscience whose results I have seen at work in Mexico, Vietnam, Haiti and Chile.” (Yours, etc., Letters to the Press. 1979) Mexico is a peripheral country with a difficult history, and undeniably the very long border that it shares with the most powerful nation on earth has largely determined its fate. After his trip to Mexico in 1938, Greene had very hard words to say about the latter country, but then he spoke with equal harshness about the “hell” he had left behind in his English birthplace, Berkhamsted. He “loathed” Mexico…” but there were times when it seemed as if there were worse places. Mexico “was idolatry and oppression, starvation and casual violence, but you lived under the shadow of religion – of God or the Devil.” However, the United States was worse: “It wasn’t evil, it wasn’t anything at all, it was just the drugstore and the Coca Cola, the hamburger, the sinless empty graceless chromium world.” (Lawless Roads) He also expressed abhorrence for what he saw on the German ship that took him back to Europe: “Spanish violence, German Stupidity, Anglo-Saxon absurdity…the whole world is exhibited in a kind of crazy montage.” (Ibidem) As war approached, he wrote: “Violence came nearer – Mexico is a state of mind.” In “the grit of the London afternoon”, he said, “I wondered why I had disliked Mexico so much.” Indeed, upon asking himself why Mexico had seemed so bad and London so good, he responded: “I couldn’t remember”. -

1 Ministry of Fear 1-153 6/11/13, 10:29 Am Introduction

THE MINISTRY OF FEAR AN ENTERTAINMENT Grahame Greene Introduction by richard greene Coeor’s LıBrarY 3 1 Ministry of Fear 1-153 6/11/13, 10:29 am Introduction Spies, fugitives, double-agents, traitors, informers: Graham Greene seemed to carry these stock characters of fiction inside his skin. His imagination endowed them with moral urgency. He found in the plots of the common thriller, its concealments and duplicities, the elements of a more universal tale. His characters become the agents of the divided heart and their yearning for safety, escape, refuge, becomes a fable of the modern world. Graham Greene’s childhood would have divided any heart. Born in 1904, he was the son of a master (later headmaster) of Berkhamsted School in Hert- fordshire. After a quiet childhood, he was sent at the age of thirteen to live as a boarder in the school. This placed him on the other side of a symbolic green baize door which separated the family quarters from the school. The other boys assumed he was a Judas, reporting to his father all that happened in the dormitory. Two of his friends subjected him to elaborate mental cruelties, which he recalled as torture. Greene fell apart, made attempts at suicide, and eventually ran away to Berkhamsted Common, intending to become, as he wrote in his autobio- graphy, A Sort of Life (1971), ‘an invisible watcher, a spy on all that went on’. His parents brought him back into the family quarters, but he was never the same. In a family with a devastating history of mental illness, he showed signs of depression and instability.