Some Reflections on Links and Contrasts Between Graham Greene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

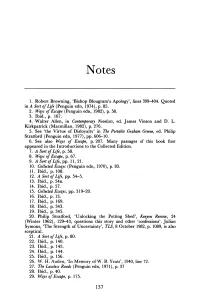

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

Norman Macleod

Norman Macleod "This strange, rather sad story": The Reflexive Design of Graham Greene's The Third Man. The circumstances surrounding the genesis and composition of Gra ham Greene's The Third Man ( 1950) have recently been recalled by Judy Adamson and Philip Stratford, in an essay1 largely devoted to characterizing some quite unwarranted editorial emendations which differentiate the earliest American editions from British (and other textually sound) versions of The Third Man. It turns out that these are changes which had the effect of giving the American reader a text which (for whatever reasons, possibly political) presented the Ameri can and Russian occupation forces in Vienna, and the central charac ter of Harry Lime, and his dishonourable deeds and connections, in a blander, softer light than Greene could ever have intended; indeed, according to Adamson and Stratford, Greene did not "know of the extensive changes made to his story in the American book and now claims to be 'horrified' by them"2 • Such obscurely purposeful editorial meddlings are perhaps the kind of thing that the textual and creative history of The Third Man could have led us to expect: they can be placed alongside other more official changes (usually introduced with Greene's approval and frequently of his own doing) which befell the original tale in its transposition from idea-resuscitated-from-old notebook to story to treatment to script to finished film. Adamson and Stratford show that these approved and 'official' changes involved revisions both of dramatis personae and of plot, and that they were often introduced for good artistic or practical reasons. -

Orwellian Methods of Social Control in Contemporary Dystopian Literature

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio Documental de la Universidad de Valladolid FACULTAD de FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO de FILOLOGÍA INGLESA Grado en Estudios Ingleses TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO A Nightmarish Tomorrow: Orwellian Methods of Social Control in Contemporary Dystopian Literature Pablo Peláez Galán Tutora: Tamara Pérez Fernández 2014/2015 ABSTRACT Dystopian literature is considered a branch of science fiction which writers use to portray a futuristic dark vision of the world, generally dominated by technology and a totalitarian ruling government that makes use of whatever means it finds necessary to exert a complete control over its citizens. George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) is considered a landmark of the dystopian genre by portraying a futuristic London ruled by a totalitarian, fascist party whose main aim is the complete control over its citizens. This paper will analyze two examples of contemporary dystopian literature, Philip K. Dick’s “Faith of Our Fathers” (1967) and Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta (1982-1985), to see the influence that Orwell’s dystopia played in their construction. It will focus on how these two works took Orwell’s depiction of a totalitarian state and the different methods of control it employs to keep citizens under complete control and submission, and how they apply them into their stories. KEYWORDS: Orwell, V for Vendetta , Faith of Our Fathers, social control, manipulation, submission. La literatura distópica es considerada una rama de la ciencia ficción, usada por los escritores para retratar una visión oscura y futurista del mundo, normalmente dominado por la tecnología y por un gobierno totalitario que hace uso de todos los medios que sean necesarios para ejercer un control total sobre sus ciudadanos. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

The Destructors Graham Greene

The Destructors Graham Greene Online Information For the online version of BookRags' The Destructors Premium Study Guide, including complete copyright information, please visit: http://www.bookrags.com/studyguide-destructors/ Copyright Information ©2000-2007 BookRags, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. The following sections of this BookRags Premium Study Guide is offprint from Gale's For Students Series: Presenting Analysis, Context, and Criticism on Commonly Studied Works: Introduction, Author Biography, Plot Summary, Characters, Themes, Style, Historical Context, Critical Overview, Criticism and Critical Essays, Media Adaptations, Topics for Further Study, Compare & Contrast, What Do I Read Next?, For Further Study, and Sources. ©1998-2002; ©2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design® and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Encyclopedia of Popular Fiction: "Social Concerns", "Thematic Overview", "Techniques", "Literary Precedents", "Key Questions", "Related Titles", "Adaptations", "Related Web Sites". © 1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Guide to Literature for Young Adults: "About the Author", "Overview", "Setting", "Literary Qualities", "Social Sensitivity", "Topics for Discussion", "Ideas for Reports and Papers". © 1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. All other sections in this Literature Study Guide are owned and copywritten by BookRags, Inc. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

Nineteen Eighty-Four

MGiordano Lingua Inglese II Nineteen Eighty-Four Adapted from : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nineteen_Eighty-Four Nineteen Eighty-Four, sometimes published as 1984, is a dystopian novel by George Orwell published in 1949. The novel is set in Airstrip One (formerly known as Great Britain), a province of the superstate Oceania in a world of perpetual war, omnipresent government surveillance, and public manipulation, dictated by a political system euphemistically named English Socialism (or Ingsoc in the government's invented language, Newspeak) under the control of a privileged Inner Party elite that persecutes all individualism and independent thinking as "thoughtcrimes". The tyranny is epitomised by Big Brother, the quasi-divine Party leader who enjoys an intense cult of personality, but who may not even exist. The Party "seeks power entirely for its own sake. We are not interested in the good of others; we are interested solely in power." The protagonist of the novel, Winston Smith, is a member of the Outer Party who works for the Ministry of Truth (or Minitrue), which is responsible for propaganda and historical revisionism. His job is to rewrite past newspaper articles so that the historical record always supports the current party line. Smith is a diligent and skillful worker, but he secretly hates the Party and dreams of rebellion against Big Brother. As literary political fiction and dystopian science-fiction, Nineteen Eighty-Four is a classic novel in content, plot, and style. Many of its terms and concepts, such as Big Brother, doublethink, thoughtcrime, Newspeak, Room 101, Telescreen, 2 + 2 = 5, and memory hole, have entered everyday use since its publication in 1949. -

Year 8 English Extract Pack

Year 8 English Extract Pack Extract 1- for Task 1 George Orwell George Orwell was the pen name of a man called Eric Blair. A pen name is a name used by a writer instead of their own name. Even though his real name was Eric Blair, he is known as his pen name, George Orwell. Early Life George Orwell was born in India in 1903. At the time, India was still one of Britain’s colonies. You may remember from The Tempest that a colony is a country that is controlled by a different country. At the time, India was a British colony, so many British people lived and worked in India. Orwell’s father worked as a civil servant in India. Even though he was helping to run India, he was employed by the British government as India was a part of the British Empire. When he was one, Orwell moved back to live in England with his mother. He did not see his father again until 1912, as his father had to stay in India for work. The young Orwell was very intelligent. He went to exclusive boarding schools as he was growing up. He only had to pay half the fees for his education because he was so smart. At these exclusive schools, Orwell spent a lot of time around the richest people in the country. But when he read the newspapers he saw that the majority of people around the world were not rich. He wanted to find out more about these people and their lives. -

Report to UCL Octagon Small Grants Fund Sarah Gibbs 1 Conference: Rebel? Prophet? Relic? Perspectives on George Orwell in 2019

Report to UCL Octagon Small Grants Fund Sarah Gibbs 1 Conference: Rebel? Prophet? Relic? Perspectives on George Orwell in 2019 24-25 May 2019 University College London (UCL) Conference Programme Summary UCL’s first George Orwell conference, Rebel? Prophet? Relic? Perspectives on George Orwell in 2019, took place on May 24th and 25th. The event explored all aspects of the author’s oeuvre and presence in popular culture, from the continuing significance of his masterpiece, the political dystopia Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), to his relationship to the British Empire and mid-century Fascism. Panelists discussed his reception history in different parts of the world, and adaptations of his work in a variety of media. The speaker list was international, and truly interdisciplinary. Presenters, who were academics, theatre directors, video game designers, authors, journalists, and members of the Armed Forces, traveled Report to UCL Octagon Small Grants Fund Sarah Gibbs 2 from Australia, Canada, Iraq, the United States, China, Germany, Scotland, and all parts of England to participate. The conference brought together a number of Orwell-focused organizations and institutions: the Orwell Foundation, the Orwell Society, and UCL Special Collections, holder of the Orwell Archive. Approximately forty members of the public also joined the event. The support of the Octagon Small Grants Fund not only allowed scholars to participate in a conference dedicated to Orwell, very few of which exist, but also enabled the University to positively engage with the community and publicize its projects and collections. Twitter: @UCL_Orwell_2019; #UCLOrwell2019 Report In 1945, George Orwell wrote of war-time rumours that American troops had come to England to thwart a communist revolution: “One has to belong to the intelligentsia to believe things like that. -

THE HEART of the MATTER by Graham Greene

THE HEART OF THE MATTER by Graham Greene THE AUTHOR Graham Greene (1904-1991) was born in Berkhamsted, England. He had a very troubled childhood, was bullied in school, on several occasions attempted suicide by playing Russian roulette, and eventually was referred for psychiatric help. Writing became an important outlet for his painful inner life. He took a degree in History at Oxford, then began work as a journalist. His conversion to Catholicism at the age of 22 was due largely to the influence of his wife-to-be, though he later became a devout follower of his chosen faith. His writing career included novels, short stories, and plays. Some of his novels dealt openly with Catholic themes, including The Power and the Glory (1940), The Heart of the Matter (1948), and The End of the Affair (1951), though the Vatican strongly disapproved of his portrayal of the dark side of man and the corruption in the Church and in the world. Others were based on his travel experiences, often to troubled parts of the world, including Mexico during a time of religious persecution, which produced The Lawless Roads (1939) as well as The Power and the Glory, The Quiet American (1955) about Vietnam, Our Man in Havana (1958) about Cuba, The Comedians (1966) about Haiti, The Honorary Consul (1973) about Paraguay, and The Human Factor (1978) about South Africa. Many of his novels were later made into films. Greene was also considered one of the finest film critics of his day, though one particularly sharp review attracted a libel suit from the studio producing Shirley Temple films when he suggested that the sexualization of children was likely to appeal to pedophiles. -

Lights and Shadows in George Orwell's Homage to Catalonia

Paul Preston Lights and shadows in George Orwell's Homage to Catalonia Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Preston, Paul (2017) Lights and shadows in George Orwell's Homage to Catalonia. Bulletin of Spanish Studies. ISSN 1475-3820 DOI: 10.1080/14753820.2018.1388550 © 2017 The Author This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/85333/ Available in LSE Research Online: November 2017 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Lights and Shadows in George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia PAUL PRESTON London School of Economics Despite its misleading title, Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia is almost certainly the most sold and most read book about the Spanish Civil War. It is a vivid and well-written account of some fragments of the war by an acute witness. -

George Orwell's Down and out in Paris and London

/V /o THE POLITICS OF POVERTY: GEORGE ORWELL'S DOWN AND OUT IN PARIS AND LONDON THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For-the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Marianne Perkins, B.A. Denton, Texas May, 1992 Perkins, Marianne, The Politics of Poverty: George Orwell's Down and Out in Paris and London. Master of Arts (Literature), May, 1992, 65 pp., bibliography, 73 titles. Down and Out in Paris and London is typically perceived as non-political. Orwell's first book, it examines his life with the poor in two cities. Although on the surface Down and Out seems not to be about politics, Orwell covertly conveys a political message. This is contrary to popular critical opinion. What most critics fail to acknowledge is that Orwell wrote for a middle- and upper-class audience, showing a previously unseen view of the poor. In this he suggests change to the policy makers who are able to bring about improvements for the impoverished. Down and Out is often ignored by both critics and readers of Orwell. With an examination of Orwell's politicizing background, and of the way he chooses to present himself and his poor characters in Down and Out, I argue that the book is both political and characteristic of Orwell's later work. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. ORWELL'S PAST AND MOTIVATION. ......... Biographical Information Critical Reaction Comparisons to Other Authors II. GIVING THE WEALTHY AN ACCURATE PICTURE ... .. 16 Publication Audience Characters III. ORWELL'S FUTURE INFLUENCED BY HIS PAST...