Alphachatterbox - Xiaomi and Technology in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society

The London School of Economics and Political Science Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society Magdalena Wong A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London December 2016 1 DECLARATION I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/ PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 97,927 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I confirm that different sections of my thesis were copy edited by Tiffany Wong, Emma Holland and Eona Bell for conventions of language, spelling and grammar. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how a hegemonic ideal that I refer to as the ‘able-responsible man' dominates the discourse and performance of masculinity in the city of Nanchong in Southwest China. This ideal, which is at the core of the modern folk theory of masculinity in Nanchong, centres on notions of men's ability (nengli) and responsibility (zeren). -

Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences, 8(3), 2020, 96-110 DOI: 10.15604/Ejss.2020.08.03.002

Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences, 8(3), 2020, 96-110 DOI: 10.15604/ejss.2020.08.03.002 EURASIAN JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES www.eurasianpublications.com XIAOMI – TRANSFORMING THE COMPETITIVE SMARTPHONE MARKET TO BECOME A MAJOR PLAYER Leo Sun HELP University, Malaysia Email: [email protected] Chung Tin Fah Corresponding Author: HELP University, Malaysia Email: [email protected] Received: August 12, 2020 Accepted: September 2, 2020 Abstract Over the past six years, (between the period 2014 -2019), China's electronic information industry and mobile Internet industry has morphed rapidly in line with its economic performance. This is attributable to the strong cooperation between smart phones and the mobile Internet, capitalizing on the rapid development of mobile terminal functions. The mobile Internet is the underlying contributor to the competitive environment of the entire Chinese smartphone industry. Xiaomi began its operations with the launch of its Android-based firmware MIUI (pronounced “Me You I”) in August 2010; a modified and hardcoded user interface, incorporating features from Apple’s IOS and Samsung’s TouchWizUI. As of 2018, Xiaomi is the world’s fourth largest smartphone manufacturer, and it has expanded its products and services to include a wider range of consumer electronics and a smart home device ecosystem. It is a company focused on developing new- generation smartphone software, and Xiaomi operated a successful mobile Internet business. Xiaomi has three core products: Mi Chat, MIUI and Xiaomi smartphones. This paper will use business management models from PEST, Porter’s five forces and SWOT to analyze the internal and external environment of Xiaomi. Finally, the paper evaluates whether Xiaomi has a strategic model of sustainable development, strategic flaws and recommend some suggestions to overcome them. -

TCL 科技集团股份有限公司 TCL Technology Group Corporation

TCL Technology Group Corporation Annual Report 2019 TCL 科技集团股份有限公司 TCL Technology Group Corporation ANNUAL REPORT 2019 31 March 2020 1 TCL Technology Group Corporation Annual Report 2019 Table of Contents Part I Important Notes, Table of Contents and Definitions .................................................. 8 Part II Corporate Information and Key Financial Information ........................................... 11 Part III Business Summary .........................................................................................................17 Part IV Directors’ Report .............................................................................................................22 Part V Significant Events ............................................................................................................51 Part VI Share Changes and Shareholder Information .........................................................84 Part VII Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Staff .......................................93 Part VIII Corporate Governance ..............................................................................................113 Part IX Corporate Bonds .......................................................................................................... 129 Part X Financial Report............................................................................................................. 138 2 TCL Technology Group Corporation Annual Report 2019 Achieve Global Leadership by Innovation and Efficiency Chairman’s -

Women's Development in Guangdong; Unequal Opportunities and Limited Development in a Market Economy

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2012 Women's Development in Guangdong; Unequal Opportunities and Limited Development in a Market Economy Ying Hua Yue CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/169 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Running head: WOMEN’S DEVELOPMENT IN GUANGDONG 1 Women’s Development in Guangdong: Unequal Opportunities and Limited Development in a Market Economy Yinghua Yue The City College of New York In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sociology Fall 2012 WOMEN’ S DEVELOPMENT IN GUANGDONG 2 ABSTRACT In the context of China’s three-decade market-oriented economic reform, in which economic development has long been prioritized, women’s development, as one of the social undertakings peripheral to economic development, has relatively lagged behind. This research is an attempt to unfold the current situation of women’s development within such context by studying the case of Guangdong -- the province as forerunner of China’s economic reform and opening-up -- drawing on current primary resources. First, this study reveals mixed results for women’s development in Guangdong: achievements have been made in education, employment and political participation in terms of “rates” and “numbers,” and small “breakthroughs” have taken place in legislation and women’s awareness of their equal rights and interests; however, limitations and challenges, like disparities between different women groups in addition to gender disparity, continue to exist. -

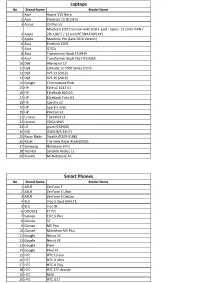

Type-C Compatible Device List 1.Xlsx

Laptops No Brand Name Model Name 1 Acer Aspire V15 Nitro 2 Acer Predator 15 (N15P3) 3 Aorus X3 Plus v5 MacBook (2015 version with USB-C port - Specs: 13.1mm THIN / 4 Apple 2lb. LIGHT / 12-inch RETINA DISPLAY) 5 Apple MacBook Pro (Late 2016 Version) 6 Asus EeeBook E202 7 Asus G752v 8 Asus Transformer Book T100HA 9 Asus Transformer Book Flip (TP200SA) 10 Dell Alienware 17 11 Dell Latitude 12 7000 Series (7275 12 Dell XPS 13 (2016) 13 Dell XPS 15 (2016) 14 Google Chromebook Pixel 15 HP Elite x2 1012 G1 16 HP EliteBook 840 G3 17 HP EliteBook Folio G1 18 HP Spectre x2 19 HP Spectre x360 20 HP Pavilion x2 21 Lenovo ThinkPad 13 22 Lenovo YOGA 900S 23 LG gram (15Z960) 24 MSI GS60 (MS-16H7) 25 Razer Blade Stealth (RZ09-0168) 26 Razer The New Razer Blade(2016) 27 Samsung Notebook 9 Pro 28 Toshiba Satellite Radius 12 29 Xiaomi Mi Notebook Air Smart Phones No Brand Name Model Name 1 ASUS ZenFone 3 2 ASUS ZenFone 3 Ultra 3 ASUS ZenFone 3 Deluxe 4 BLU Vivo 5 Dual SIM LTE 5 BLU Vivo XL 6 DOOGEE F7 Pro 7 Gionee Elife S Plus 8 Gionee S6 9 Gionee M5 Plus 10 Gionee Marathon M5 Plus 11 Google Nexus 5X 12 Google Nexus 6P 13 Google Pixel 14 Google Pixel XL 15 HTC HTC 10 evo 16 HTC HTC U Ultra 17 HTC HTC U Play 18 HTC HTC 10 Lifestyle 19 HTC M10 20 HTC HTC U11 21 Huawei Honor 22 Huawei Honor 8 23 Huawei Honor 9 24 Huawei Honor Magic 25 Huawei Hornor V9 26 Huawei Mate 9 27 Huawei Mate 9 Pro 28 Huawei Mate 9 Porsche Design 29 Huawei Nexus 6P 30 Huawei Nova2 31 Huawei P9 32 Huawei P10 33 Huawei P10 Plus 34 Huawei V8 35 Lenovo ZUK Z1(China) 36 Lenovo Zuk Z2 37 -

Five Forces Analysis Based on Xiaomi, a Chinese Smartphone Company Wang, Jiaying1

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 182 Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Economic Development and Business Culture (ICEDBC 2021) Five Forces Analysis Based on Xiaomi, a Chinese Smartphone Company Wang, Jiaying1 1Xi'an Teiyi High School, Xi’an, 710054, China [email protected] ABSTRACT As the development of technology and the spread of information, people’s desire and needs of smartphone increases dramatically. Admittedly, smartphone plays a crucial role in human being’s daily life as people use it as communication tools, game device, and portable office device. This paper analyzes one of the most famous smartphone brand in China -- Xiaomi to fully understand how it stands out in the industry. This analysis is mainly based upon Five Forces methodology to fully explain how Xiaomi operates and behaves in the smartphone industry. Keywords: smartphone, five forces analysis, business strategy, IoT, AIoT. 1. INTRODUCTION 2. FIVE FORCES ANALYSIS This report mainly focuses on Xiaomi, a Chinese smartphone brand and the world’s third-largest 2.1. Competitive Rivalry smartphone marker. The below report will be analyzed using the Five Forces methodology, which is a famous With the popularity of the Internet, the size of the business strategy tool to analyze a company’s smartphone industry market has been enlarged with competence in its industry. Five Forces analysis includes more brands joining the fierce competition. Customers competitive rivalry, the threat of entry, the threat of have more options when it comes to picking the right substitutes, supplier power, and buyer power. phones for themselves. Even in China, Xiaomi has to face many other competitive rivals like Huawei, OPPO, Xiaomi’s mission is to produce high-quality products and Vivo, etc, let alone the brands outside the country at affordable prices [1]. -

Statistics of Chinese SEP Cases in 2011-2019

Statistics of Chinese SEP Cases in 2011-2019 ZHAO Qishan, LU Zhe LexField Law Offices From 2011 to December 2019, Chinese courts accepted 160 cases related to SEPs. Most of the cases involve foreign entities and relate to the telecommunication industry. Most of the cases were filed with the courts in Beijing, Guangdong, Shanghai and Jiangsu. Most of the cases are patent infringement disputes, while cases asking the court to determine FRAND terms during license negotiations are also on the rise. This report includes a quantitative analysis from annual distribution, parties involved, geographic distribution of the courts, causes of action, adjudication progress and final outcomes, and also provides a particular summary of the SEP cases accepted in 2018 and 2019.1 From 2011 to 2019, Chinese courts have accepted over one hundred cases involving standard essential patents (“SEPs”) and Chinese judges have accumulated considerable judicial experience in hearing the cases. Aiming to provide a complete overview, this report analyzes information related to these SEP cases from various aspects based on the following methodology: (1) Scope of cases reviewed: The cases covered in the report are those accepted by civil courts in mainland China where the plaintiffs claimed or the defendants argued that the asserted patents were SEPs. Such cases are collectively referred to as "SEP cases" in this report. Cases that were withdrawn or dismissed due to the invalidation of asserted patents are also covered. (2) Time span: The cases included in the report are accepted by Chinese court from 2011 to December 2019. Since 2011, the number of Chinses SEP cases has gradually increased, and types of the cases have also become diversified. -

1 | Page PROJECT REPORT ON: a STUDY on MARKETING

PROJECT REPORT ON: A STUDY ON MARKETING STRATERGY OF ONE PLUS AND ITS EFFECTS ON CONSUMERS OF MUMBAI REGION SUBMITTED BY: DIVYA PUJARI T.Y. ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE (SEMESTER 6) SUBMITTED TO: PROJECT GUIDE: DR. NISHIKANT JHA ACADEMIC YEAR 2019-2020 1 | Page DECLARATION I DIVYA PUJARI FROM THAKUR COLLEGE OF SCIENCE AND COMMERCE STUDENT OF T.Y.BAF (ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE) SEM 6 HEREBY SUBMIT MY PROJECT ON “A STUDY ON MARKETING STRATEGIES OF ONE PLUS AND ITS EFFECTS ON CONSUMERS IN MUMBAI REGION” I ALSO DECLARE THAT THIS PROJECT WHICH IS PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE T.Y. BCOM (ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE) OFFERED BY UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI IS THE RESULT OF MY OWN EFFORTS WITH THE HELP OF EXPERTS DIVYA PUJARI DATE: PLACE: 2 | Page CERTIFICATE THIS IS TO CERTIFY THE PROJECT ENTITLED IS SUCCESSFULLY DONE BY DIVYA PUJARI DURING THE THIRD YEAR SIXTH SEMESTER FROM THAKUR COLLEGE OF SCIENCE AND COMMERCE KANDIVALI (EAST) MUMBAI:400101 COORDINATOR PROJECT GUIDE PRINCIPAL INTERNAL EXAMINER EXTERNAL EXAMINER 3 | Page PROJECT REPORT ON: A STUDY ON MARKETING STRATEGIES OF ONE PLUS SIMILARITY INDEX FOUND: 11.4% Date:12 February 2020 Statistics: 2591 words plagiarized/ 22734 words in total Remarks: Low plagiarism report 4 | Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENT To list who all have helped me is difficult because they are so numerous and the depth is so enormous. I would like to acknowledge the following as being idealistic channels and fresh dimensions in the completion of this project. I take this opportunity to thank the University of Mumbai for giving me chance to do this project. -

The Multiple Forces Behind Chinese Students' Self-Segregation and How We May Counter Them Vicki Jingjing Zhang University of Toronto

Forces Behind Chinese Student’s Self-segregation August, 2018 The Multiple Forces Behind Chinese Students' Self-segregation and How We May Counter Them Vicki Jingjing Zhang University of Toronto Author's Contact Information Vicki Jingjing Zhang, Assistant Professor, Teaching Stream University of Toronto 100 St. George Street, Toronto, ON M5S 3G3, Canada Phone: 647-402-9355 Email: [email protected] Abstract: With the internationalization of Higher Education in Canada, universities have been striving to provide a welcoming and inclusive environment for international students. However, sometimes their efforts fall short due to a lack of deep understanding of the international student body. This study focuses on one particular international student group – students from mainland China - and aims to uncover some of the crucial reasons behind the widely reported self-segregation of Chinese students (Cheng & Erben, 2011). It sets to understand why many students from mainland China feel offended and turned off by cross-national communications with students from the host nation (Dewan, 2008). I employed various frameworks to understand the findings from the study, including host nation hostipitality, social psychology and group identity, and the impact of colonial mentality and Chinese nationalism. The goal of the study is to shed light on strategies educators may employ to help mitigate the self-segregation pattern among Chinese international students and encourage more inclusive learning environments and communities. Key Words: Chinese international students, cross-national communication, self-segregation, internationalization of higher education, inclusive learning community. Introduction In the Fall of 2004 I left China to pursue graduate studies in the United States. I was at the tail end of a generation of mainland Chinese students who had toiled through the high-pressure, borderline-draconian education system in China, and jostled for the few spots at reputable graduate schools in the United States. -

The Problem Faced and the Solution of Xiaomi Company in India

ISSN: 2278-3369 International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics Available online at: www.managementjournal.info RESEARCH ARTICLE The Problem Faced and the Solution of Xiaomi Company in India Li Kai-Sheng International Business School, Jinan University, Qianshan, Zhuhai, Guangdong, China. Abstract This paper mainly talked about the problem faced and the recommend solution of Xiaomi Company in India. The first two parts are introduction and why Xiaomi targeting at the India respectively. The third part is the three problems faced when Xiaomi operate on India, first is low brand awareness can’t attract consumes; second, lack of patent reserves and Standard Essential Patent which result in patent dispute; at last, the quality problems after-sales service problems which will influence the purchase intention and word of mouth. The fourth part analysis the cause of the problem by the SWOT analysis of Xiaomi. The fifth part is the decision criteria and alternative solutions for the problems proposed above. The last part has described the recommend solution, in short, firstly, make good use of original advantage and increase the advertising investment in spokesman and TV show; then, in long run, improve the its ability of research and development; next, increase the number of after-sales service staff and service centers, at the same, the quality of service; finally, train the local employee accept company’s culture, enhance the cross-culture management capability of managers, incentive different staff with different programs. Keywords: Cross-cultural Management, India, Mobile phone, Xiaomi. Introduction Xiaomi was founded in 2010 by serial faces different problem inevitably. -

RELEASE NOTES UFED PHYSICAL ANALYZER, Version 5.0 | March 2016 UFED LOGICAL ANALYZER

NOW SUPPORTING 19,203 DEVICE PROFILES +1,528 APP VERSIONS UFED TOUCH, UFED 4PC, RELEASE NOTES UFED PHYSICAL ANALYZER, Version 5.0 | March 2016 UFED LOGICAL ANALYZER COMMON/KNOWN HIGHLIGHTS System Images IMAGE FILTER ◼ Temporary root (ADB) solution for selected Android Focus on the relevant media files and devices running OS 4.3-5.1.1 – this capability enables file get to the evidence you need fast system and physical extraction methods and decoding from devices running OS 4.3-5.1.1 32-bit with ADB enabled. In addition, this capability enables extraction of apps data for logical extraction. This version EXTRACT DATA FROM BLOCKED APPS adds this capability for 110 devices and many more will First in the Industry – Access blocked application data with file be added in coming releases. system extraction ◼ Enhanced physical extraction while bypassing lock of 27 Samsung Android devices with APQ8084 chipset (Snapdragon 805), including Samsung Galaxy Note 4, Note Edge, and Note 4 Duos. This chipset was previously supported with UFED, but due to operating system EXCLUSIVE: UNIFY MULTIPLE EXTRACTIONS changes, this capability was temporarily unavailable. In the world of devices, operating system changes Merge multiple extractions in single unified report for more frequently, and thus, influence our support abilities. efficient investigations As our ongoing effort to continue to provide our customers with technological breakthroughs, Cellebrite Logical 10K items developed a new method to overcome this barrier. Physical 20K items 22K items ◼ File system and logical extraction and decoding support for iPhone SE Samsung Galaxy S7 and LG G5 devices. File System 15K items ◼ Physical extraction and decoding support for a new family of TomTom devices (including Go 1000 Point Trading, 4CQ01 Go 2505 Mm, 4CT50, 4CR52 Go Live 1015 and 4CS03 Go 2405). -

Technology 6 November 2017

INDUSTRY NOTE China | Technology 6 November 2017 Technology EQUITY RESEARCH China Summit Takeaway: AI, Semi, Smartphone Value Chain Key Takeaway We hosted several experts and 24 A/H corporates at our China Summit and Digital Disruption tour last week. Key takeaways: 1) AI shifting from central cloud to the edge (end devices), driving GPU/FPGA demand in near term, 2) AI leaders in China rolling out own ASICs in the next 2~3 years, 3) China's new role in semi, forging ahead in design and catching up in foundry. In smartphone value chain, maintain AAC as top pick for lens opportunity and Xiaomi strength. CHINA Artificial Intelligence - From cloud to edge computing: The rise of AI on the edge (terminal devices, like surveillance cameras, smartphones) from central cloud, can solve one key weakness of AI: the brains are located thousands of miles away from the applications. The benefits of AI on the edge include: 1) better analysis based on non-compressed raw data, which contains more information, 2) lower requirement on bandwidth, as transmitted data has been pre-processed, 3) faster response. This will keep driving the demands for GPUs and FPGAs in near term. Meanwhile, China's leading AI companies including Hikvision (002415 CH) and Unisound (private, leader in voice recognition) also noted they may develop own ASICs in the next 2~3 years, for better efficiency and low power. While machines getting smarter, we notice increasing concerns on data privacy. Governments are not only implementing Big Data laws and policies, also starts investing AI leaders, like Face ++ (computer vision) in China.