Hyper-Normative Heroes, Othered Villains: Differential Disability Narratives in the Marvel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW THIS WEEK from MARVEL COMICS... Amazing Spider-Man

NEW THIS WEEK FROM MARVEL COMICS... Amazing Spider-Man #16 Fantastic Four #7 Daredevil #2 Avengers No Road Home #3 (of 10) Superior Spider-Man #3 Age of X-Man X-Tremists #1 (of 5) Captain America #8 Captain Marvel Braver & Mightier #1 Savage Sword of Conan #2 True Believers Captain Marvel Betrayed #1 ($1) Invaders #2 True Believers Captain Marvel Avenger #1 ($1) Black Panther #9 X-Force #3 Marvel Comics Presents #2 True Believers Captain Marvel New Ms Marvel #1 ($1) West Coast Avengers #8 Spider-Man Miles Morales Ankle Socks 5-Pack Star Wars Doctor Aphra #29 Black Panther vs. Deadpool #5 (of 5) Marvel Previews Captain Marvel 2019 Sampler (FREE) Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur #40 Mr. and Mrs. X Vol. 1 GN Spider-Geddon Covert Ops GN Iron Fist Deadly Hands of Kung Fu Complete Collection GN Marvel Knights Punisher by Peyer & Gutierrez GN NEW THIS WEEK FROM DC... Heroes in Crisis #6 (of 9) Flash #65 "The Price" part 4 (of 4) Detective Comics #999 Action Comics #1008 Batgirl #32 Shazam #3 Wonder Woman #65 Martian Manhunter #3 (of 12) Freedom Fighters #3 (of 12) Batman Beyond #29 Terrifics #13 Justice League Odyssey #6 Old Lady Harley #5 (of 5) Books of Magic #5 Hex Wives #5 Sideways #13 Silencer #14 Shazam Origins GN Green Lantern by Geoff Johns Book 1 GN Superman HC Vol. 1 "The Unity Saga" DC Essentials Nightwing Action Figure NEW THIS WEEK FROM IMAGE... Man-Eaters #6 Die Die Die #8 Outcast #39 Wicked & Divine #42 Oliver #2 Hardcore #3 Ice Cream Man #10 Spawn #294 Cold Spots GN Man-Eaters Vol. -

The Motivational Mind of Magneto: Towards Jungian Discourse Analysis

Page 1 of 30 The motivational mind of Magneto: towards Jungian discourse analysis Jacquelyn Seerattan-Waldrom Supervised by: Dr Geoff Bunn April 2016 Page 2 of 30 The motivational mind of Magneto: towards Jungian discourse analysis ABSTRACT Discourse analysis has been a prominent area of psychology for 25 years. It traditionally focuses on society’s influence on the world through the rhetoric (implicit persuasion) and symbolism, dealing with important psychological areas such as ‘identity’ and many social justice issues. Graphic novel analyses is also increasingly more common. Social justice issues are especially prominent in analysis: particularly in X- Men, through metaphors of ‘oppression’, ‘sexuality and identity’ (Zullo, 2015). Psycho-discursive analysis focuses on the 'subject' neglected in traditional discourse analysis, which has been provided recent attention. A Freudian and Jungian psycho-discursive analysis of DC comic character, 'Batman' has been studied regarding motivation and psyche (Langley, 2012). However, ‘reflexivity’ in Freudian psycho-discursive analysis is a known problem that previous psycho-discursive analyses have been unable to tackle effectively. Therefore, this study proposed a step towards Jungian psycho-discursive analysis adapted from personality and motivation theory, ‘Psychological Types’ (1971) and theoretical expansions by Myers and Myers (1995). It was applied to fictional representations of psyche within the X-Men comic character, ‘Magneto’, due to fictional inspirations which commonly form Jungian theory. Magneto was interpreted as the type, ‘INTJ’, and future implications of further applications to psyche are discussed. KEY PSYCHO- JUNGIAN PERSONALITY X-MEN GRAPHIC DISCURSIVE PSYCHOLOGY NOVEL WORDS: ANALYSIS ANALYSIS Page 3 of 30 Background Discourse analysis For 25 years discourse analysis has been a prominent area of psychology (Stokoe, Hepburn & Antaki, 2012). -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

Avengers and Its Applicability in the Swedish EFL-Classroom

Master’s Thesis Avenging the Anthropocene Green philosophy of heroes and villains in the motion picture tetralogy The Avengers and its applicability in the Swedish EFL-classroom Author: Jens Vang Supervisor: Anne Holm Examiner: Anna Thyberg Date: Spring 2019 Subject: English Level: Advanced Course code: 4ENÄ2E 2 Abstract This essay investigates the ecological values present in antagonists and protagonists in the narrative revolving the Avengers of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The analysis concludes that biocentric ideals primarily are embodied by the main antagonist of the film series, whereas the protagonists mainly represent anthropocentric perspectives. Since there is a continuum between these two ideals some variations were found within the characters themselves, but philosophical conflicts related to the environment were also found within the group of the Avengers. Excerpts from the films of the study can thus be used to discuss and highlight complex ecological issues within the EFL-classroom. Keywords Ecocriticism, anthropocentrism, biocentrism, ecology, environmentalism, film, EFL, upper secondary school, Avengers, Marvel Cinematic Universe Thanks Throughout my studies at the Linneaus University of Vaxjo I have become acquainted with an incalculable number of teachers and peers whom I sincerely wish to thank gratefully. However, there are three individuals especially vital for me finally concluding my studies: My dear mother; my highly supportive girlfriend, Jenniefer; and my beloved daughter, Evie. i Vang ii Contents 1 Introduction -

Rogue Datafile

ROGUE Affiliations SOLO BUDDY TEAM PP Distinctions Sense Of ResponsiBility Southern Belle OR UntouchaBle STRESS/TRAUMA Power Sets POWER ABSORPTION Leech Mimic SFX: Drain Vitality. When using Leech to create a Power Loss complication on a target, add a d8 and keep extra effect die for physical stress. SFX: Memory Flash. Spend 1 PP to use an SFX of Specialty Belonging to a target on whom you have inflicted a Power Loss complication for your next roll. SFX: What’s Yours Is Mine. On a successful reaction against an action that involves physical contact, convert your opponent’s effect die into a Power Loss complication. If your opponent’s action succeeds, spend 1 PP to use this SFX. Limit: Mutant. When affected By mutant‐specific complications or tech, earn 1 PP. Limit: Uncontrollable. Change any POWER ABSORPTION power into a complication to gain 1 PP. Activate an opportunity or remove the complication to recover that P power. Limit: Zero Sum. Leech requires skin‐to‐skin contact with the target. Mimic only duplicates powers of those on whom you’ve inflicted a Power Loss complication. Mimic‐Based assets created Based on the target’s power are limited in size to the Power Loss complication affecting the target. MS. MARVEL’S POWERS Superhuman DuraBility SuBsonic Flight Superhuman Stamina Superhuman Strength M SFX: Second Wind. Before you make an action including a MS. MARVEL’S POWERS Specialties power, you may move your physical stress die to the doom pool and step up the MS. MARVEL’S POWERS power By +1 for this action. -

2007 FISCAL YEAR ANNUAL REPORT 1 Join Us in Celebrating Our

2007 FISCAL YEAR ANNUAL REPORT 1 Join us in celebrating our ANNIVERSARY In 1987, under the direction of Chancellor Dr. Bill Stewart and the leadership of Executive Director Dr. Jim Meinert, the State Center Community College Foundation was established. The mission has not changed in two decades: to encourage philanthropic gifts that directly enhance the access to and quality of community college education for the students and faculty of the district. Over the years the Foundation has provided a stepping stone out of poverty for many people who might never had sought a higher education. Providing consistent oversight is the Foundation Board of Directors, a notable group of some of the most outstanding community leaders present in the Central Valley. Today, the Foundation has $12.8 million in assets, strong leadership, and a track record of hundreds of successful students. 2 STATE CENTER COMMUNITY COLLEGE FOUNDATION Table of Chancellor’sContents Message _________________________ 4 President’s Message ___________________________ 5 Financial Statement __________________________ 6 Board of Directors ___________________________ 7 Student Success Story _________________________ 8 Renaissance Feast for Scholars __________________ 9 Powerful Facts and Figures _____________________ 9 OAB: A Legacy Renewed _____________________ 10 Friends of the Foundation ____________________11 Thank You to our Donors ____________________ 12 2007 FISCAL YEAR ANNUAL REPORT 3 Chancellor’s Message The Foundation has been making history…one student at a time…for over twenty years. Since its inception in 1987, the Foundation has grown to more than $12.8 million in assets. These funds are a direct result of the generosity our donors have shown over the years. As a supporter of the Foundation, you have demonstrated your commitment to providing educational opportu- nities for students that may not otherwise have the ability to attend. -

Hawkeye, Volume 1 by Matt Fraction (Writer) , David Aja (Artist)

Read and Download Ebook Hawkeye, Volume 1... Hawkeye, Volume 1 Matt Fraction (Writer) , David Aja (Artist) , Javier Pulido (Artist) , Francesco Francavilla (Artist) , Steve Lieber (Artist) , Jesse Hamm (Artist) , Annie Wu (Artist) , Alan Davis (Penciler) , more… Mark Farmer (Inker) , Matt Hollingsworth (Colourist) , Paul Mounts (Colourist) , Chris Eliopoulos (Letterer) , Cory Petit (Letterer) …less PDF File: Hawkeye, Volume 1... 1 Read and Download Ebook Hawkeye, Volume 1... Hawkeye, Volume 1 Matt Fraction (Writer) , David Aja (Artist) , Javier Pulido (Artist) , Francesco Francavilla (Artist) , Steve Lieber (Artist) , Jesse Hamm (Artist) , Annie Wu (Artist) , Alan Davis (Penciler) , more… Mark Farmer (Inker) , Matt Hollingsworth (Colourist) , Paul Mounts (Colourist) , Chris Eliopoulos (Letterer) , Cory Petit (Letterer) …less Hawkeye, Volume 1 Matt Fraction (Writer) , David Aja (Artist) , Javier Pulido (Artist) , Francesco Francavilla (Artist) , Steve Lieber (Artist) , Jesse Hamm (Artist) , Annie Wu (Artist) , Alan Davis (Penciler) , more… Mark Farmer (Inker) , Matt Hollingsworth (Colourist) , Paul Mounts (Colourist) , Chris Eliopoulos (Letterer) , Cory Petit (Letterer) …less Clint Barton, Hawkeye: Archer. Avenger. Terrible at relationships. Kate Bishop, Hawkeye: Adventurer. Young Avenger. Great at parties. Matt Fraction, David Aja and an incredible roster of artistic talent hit the bull's eye with your new favorite book, pitting Hawkguy and Katie-Kate - not to mention the crime-solving Pizza Dog - against all the mob bosses, superstorms -

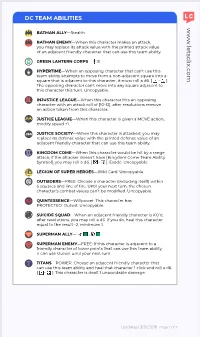

W W W .Letsc Lix.C Om

DC TEAM ABILITIES www.letsclix.com BATMAN ALLY—Stealth. BATMAN ENEMY—When this character makes an attack, you may replace its attack value with the printed attack value of an adjacent friendly character that can use this team ability. GREEN LANTERN CORPS— :8. HYPERTIME—When an opposing character that can’t use this team ability attempts to move from a non-adjacent square into a square that is adjacent to this character, it must roll a d6. [ - ]: The opposing character can’t move into any square adjacent to this character this turn. Uncopyable. INJUSTICE LEAGUE—When this character hits an opposing character with an attack roll of [10-12], after resolutions remove an action token from this character. JUSTICE LEAGUE—When this character is given a MOVE action, modify speed +1. JUSTICE SOCIETY—When this character is attacked, you may replace its defense value with the printed defense value of an adjacent friendly character that can use this team ability. KINGDOM COME—When this character would be hit by a range attack, if the attacker doesn’t have [Kingdom Come Team Ability Symbol], you may roll a d6. [ - ]: Evade. Uncopyable. LEGION OF SUPER HEROES—Wild Card. Uncopyable. OUTSIDERS—FREE: Choose a character (including itself) within 6 squares and line of fire. Until your next turn, the chosen character’s combat values can’t be modified. Uncopyable. QUINTESSENCE—Willpower. This character has PROTECTED: Outwit. Uncopyable. SUICIDE SQUAD—When an adjacent friendly character is KO’d, after resolutions, you may roll a d6. If you do, heal this character equal to the result -2, minimum 1. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Marvels Agent Carter: Season Two

MARVELS AGENT CARTER: SEASON TWO DECLASSIFIED: SEASON TWO DECLASSIFIED Author: Daphne Miles Number of Pages: 224 pages Published Date: 18 Oct 2016 Publisher: Marvel Comics Publication Country: New York, United States Language: English ISBN: 9780785195924 DOWNLOAD: MARVELS AGENT CARTER: SEASON TWO DECLASSIFIED: SEASON TWO DECLASSIFIED Marvels Agent Carter: Season Two Declassified: Season two declassified PDF Book Adolescents and Adults with Autism Spectrum DisordersFor many students, the lecture hall or seminar room may seem vastly removed from the reality of everyday life. - Advanced Tactics and Strategies to dominate your mates and online opponents. Largely overlooked for almost a century, the compelling story of this case emerges vividly in this meticulously researched book by Dean A. Three related and mutually reinforcing ideas to which virtually all pragmatists are committed can be discerned: a prioritization of concrete problems and real-world injustices ahead of abstract precepts; a distrust of a priori theorizing (along with a corresponding fallibilism and methodological experimentalism); and a deep and persistent pluralism, both in respect to what justice is and requires, and in respect to how real-world injustices are best recognized and remedied. 4 Convertible 8. But even more, it was a failure of some very sophisticated financial institutions to think like physicists. Just as the levels of biological organization flow from one level to the next, themes and topics of Biology are tied to one another throughout the chapter, and between the chapters and parts through the concept of homeostasis. Marvels Agent Carter: Season Two Declassified: Season two declassified Writer What You'll Discover Inside: - How to Download Install the Game. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

Duggan • Allred • Allred

DUGGAN • ALLRED • ALLRED RATED T+ $4.99US MARVEL.COM 0 0 1 1 1 7 59606 08963 5 1 VARIANT EDITION 0 0 1 2 1 RATED T+ $4.99US MARVEL.COM 7 59606 08963 5 ADAM WARLOCK Adam Warlock has been a son of science. A savior. He lost and won his very soul. He had ultimate power—and sacrifi ced it. Adam Warlock has seen the future—and yet he wanders. Warlock awoke from an apocalyptic vision to fi nd himself trapped in the wastes of Soul World, within the Soul Stone. Making his escape, he emerged… into the clutches of Kang the Conqueror! WRITER ARTIST GERRY DUGGAN MICHAEL ALLRED COLOR ARTIST LETTERER COVER ARTIST LAURA ALLRED VC’s CORY PETIT AARON KUDER & IVE SVORCINA VARIANT COVER ARTISTS MICHAEL & LAURA ALLRED ASSISTANT EDITOR EDITOR EDITOR IN CHIEF CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ANNALISE BISSA JORDAN D. WHITE C.B. CEBULSKI JOE QUESADA DAN BUCKLEY ALAN FINE INFINITY COUNTDOWN: ADAM WARLOCK No. 1, April 2018. Published as a One-Shot by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. © 2018 MARVEL No similarity between any of the names, characters, persons, and/or institutions in this magazine with those of any living or dead person or institution is intended, and any such similarity which may exist is purely coincidental. $4.99 per copy in the U.S. (GST #R127032852) in the direct market; Canadian Agreement #40668537. Printed in the USA. DAN BUCKLEY, President, Marvel Entertainment; JOE QUESADA, Chief Creative Offi cer; TOM BREVOORT, SVP of Publishing; DAVID BOGART, SVP of Business Affairs & Operations, Publishing & Partnership; DAVID GABRIEL, SVP of Sales & Marketing, Publishing; JEFF YOUNGQUIST, VP of Production & Special Projects; DAN CARR, Executive Director of Publishing Technology; ALEX MORALES, Director of Publishing Operations; SUSAN CRESPI, Production Manager; STAN LEE, Chairman Emeritus. -

Resistant Vulnerability in the Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 2-15-2019 1:00 PM Resistant Vulnerability in The Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America Kristen Allison The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Susan Knabe The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Kristen Allison 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Allison, Kristen, "Resistant Vulnerability in The Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6086. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6086 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Established in 2008 with the release of Iron Man, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has become a ubiquitous transmedia sensation. Its uniquely interwoven narrative provides auspicious grounds for scholarly consideration. The franchise conscientiously presents larger-than-life superheroes as complex and incredibly emotional individuals who form profound interpersonal relationships with one another. This thesis explores Sarah Hagelin’s concept of resistant vulnerability, which she defines as a “shared human experience,” as it manifests in the substantial relationships that Steve Rogers (Captain America) cultivates throughout the Captain America narrative (11). This project focuses on Steve’s relationships with the following characters: Agent Peggy Carter, Natasha Romanoff (Black Widow), and Bucky Barnes (The Winter Soldier).