The Motivational Mind of Magneto: Towards Jungian Discourse Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop the DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY

$39.99 “The period covered in this volume is arguably one of the strongest in the Gould/Tracy canon, (Different in Canada) and undeniably the cartoonist’s best work since 1952's Crewy Lou continuity. “One of the best things to happen to the Brutality by both the good and bad guys is as strong and disturbing as ever…” comic market in the last few years was IDW’s decision to publish The Complete from the Introduction by Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop THE DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY NEARLY 550 SEQUENTIAL COMICS OCTOBER 1954 In Volume Sixteen—reprinting strips from October 25, 1954 THROUGH through May 13, 1956—Chester Gould presents an amazing MAY 1956 Chester Gould (1900–1985) was born in Pawnee, Oklahoma. number of memorable characters: grotesques such as the He attended Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State murderous Rughead and a 467-lb. killer named Oodles, University) before transferring to Northwestern University in health faddist George Ozone and his wild boys named Neki Chicago, from which he was graduated in 1923. He produced and Hokey, the despicable "Nothing" Yonson, and the amoral the minor comic strips Fillum Fables and The Radio Catts teenager Joe Period. He then introduces nightclub photog- before striking it big with Dick Tracy in 1931. Originally titled Plainclothes Tracy, the rechristened strip became one of turned policewoman Lizz, at a time when women on the the most successful and lauded comic strips of all time, as well force were still a rarity. Plus for the first time Gould brings as a media and merchandising sensation. -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Aliens of Marvel Universe

Index DEM's Foreword: 2 GUNA 42 RIGELLIANS 26 AJM’s Foreword: 2 HERMS 42 R'MALK'I 26 TO THE STARS: 4 HIBERS 16 ROCLITES 26 Building a Starship: 5 HORUSIANS 17 R'ZAHNIANS 27 The Milky Way Galaxy: 8 HUJAH 17 SAGITTARIANS 27 The Races of the Milky Way: 9 INTERDITES 17 SARKS 27 The Andromeda Galaxy: 35 JUDANS 17 Saurids 47 Races of the Skrull Empire: 36 KALLUSIANS 39 sidri 47 Races Opposing the Skrulls: 39 KAMADO 18 SIRIANS 27 Neutral/Noncombatant Races: 41 KAWA 42 SIRIS 28 Races from Other Galaxies 45 KLKLX 18 SIRUSITES 28 Reference points on the net 50 KODABAKS 18 SKRULLS 36 AAKON 9 Korbinites 45 SLIGS 28 A'ASKAVARII 9 KOSMOSIANS 18 S'MGGANI 28 ACHERNONIANS 9 KRONANS 19 SNEEPERS 29 A-CHILTARIANS 9 KRYLORIANS 43 SOLONS 29 ALPHA CENTAURIANS 10 KT'KN 19 SSSTH 29 ARCTURANS 10 KYMELLIANS 19 stenth 29 ASTRANS 10 LANDLAKS 20 STONIANS 30 AUTOCRONS 11 LAXIDAZIANS 20 TAURIANS 30 axi-tun 45 LEM 20 technarchy 30 BA-BANI 11 LEVIANS 20 TEKTONS 38 BADOON 11 LUMINA 21 THUVRIANS 31 BETANS 11 MAKLUANS 21 TRIBBITES 31 CENTAURIANS 12 MANDOS 43 tribunals 48 CENTURII 12 MEGANS 21 TSILN 31 CIEGRIMITES 41 MEKKANS 21 tsyrani 48 CHR’YLITES 45 mephitisoids 46 UL'LULA'NS 32 CLAVIANS 12 m'ndavians 22 VEGANS 32 CONTRAXIANS 12 MOBIANS 43 vorms 49 COURGA 13 MORANI 36 VRELLNEXIANS 32 DAKKAMITES 13 MYNDAI 22 WILAMEANIS 40 DEONISTS 13 nanda 22 WOBBS 44 DIRE WRAITHS 39 NYMENIANS 44 XANDARIANS 40 DRUFFS 41 OVOIDS 23 XANTAREANS 33 ELAN 13 PEGASUSIANS 23 XANTHA 33 ENTEMEN 14 PHANTOMS 23 Xartans 49 ERGONS 14 PHERAGOTS 44 XERONIANS 33 FLB'DBI 14 plodex 46 XIXIX 33 FOMALHAUTI 14 POPPUPIANS 24 YIRBEK 38 FONABI 15 PROCYONITES 24 YRDS 49 FORTESQUIANS 15 QUEEGA 36 ZENN-LAVIANS 34 FROMA 15 QUISTS 24 Z'NOX 38 GEGKU 39 QUONS 25 ZN'RX (Snarks) 34 GLX 16 rajaks 47 ZUNDAMITES 34 GRAMOSIANS 16 REPTOIDS 25 Races Reference Table 51 GRUNDS 16 Rhunians 25 Blank Alien Race Sheet 54 1 The Universe of Marvel: Spacecraft and Aliens for the Marvel Super Heroes Game By David Edward Martin & Andrew James McFayden With help by TY_STATES , Aunt P and the crowd from www.classicmarvel.com . -

Rogue Datafile

ROGUE Affiliations SOLO BUDDY TEAM PP Distinctions Sense Of ResponsiBility Southern Belle OR UntouchaBle STRESS/TRAUMA Power Sets POWER ABSORPTION Leech Mimic SFX: Drain Vitality. When using Leech to create a Power Loss complication on a target, add a d8 and keep extra effect die for physical stress. SFX: Memory Flash. Spend 1 PP to use an SFX of Specialty Belonging to a target on whom you have inflicted a Power Loss complication for your next roll. SFX: What’s Yours Is Mine. On a successful reaction against an action that involves physical contact, convert your opponent’s effect die into a Power Loss complication. If your opponent’s action succeeds, spend 1 PP to use this SFX. Limit: Mutant. When affected By mutant‐specific complications or tech, earn 1 PP. Limit: Uncontrollable. Change any POWER ABSORPTION power into a complication to gain 1 PP. Activate an opportunity or remove the complication to recover that P power. Limit: Zero Sum. Leech requires skin‐to‐skin contact with the target. Mimic only duplicates powers of those on whom you’ve inflicted a Power Loss complication. Mimic‐Based assets created Based on the target’s power are limited in size to the Power Loss complication affecting the target. MS. MARVEL’S POWERS Superhuman DuraBility SuBsonic Flight Superhuman Stamina Superhuman Strength M SFX: Second Wind. Before you make an action including a MS. MARVEL’S POWERS Specialties power, you may move your physical stress die to the doom pool and step up the MS. MARVEL’S POWERS power By +1 for this action. -

Sentinel's "Miss Bronze" Contest Seeks Queen for '60 OHIO STAT* Mfteu* X5TH * Tuqh-8T.F THB OHIO C0LUH3US, OHIO' SENTINEL SATURDAY, JULY 2

, •»-•-»•_• .«-•»* • • • 'iMMfaeJ^jl i w-< ..• • •<<•- .- • T"i,*'8-g>H.y' "r*|L<i" "* V r THE ©W_•• • O Sentinel's "Miss Bronze" Contest Seeks Queen For '60 OHIO STAT* mftEU* X5TH * tUQH-8T.f THB OHIO C0LUH3US, OHIO' SENTINEL SATURDAY, JULY 2. 1*60 IP 111 H HP • WkM HP • THI PEOPLE'S Interest In Horses Gets Track Job •ENTINEL CHAMPTON SPORTS CLEANINGS : • By BILL BELL • Sport. Editor VOL. 12, No. 4 THURSDAY, JULY 7, 1960 20 CENTS COLUMBUS, OHIO • CONGRATULATIONS andAhanks to the Merry Makers club, for through their generosity the Ohio track club will be able to send its complete team of ten girls to the National AAU Wom en's Track and Field championships; also to the Olympic tryoute Local Families Hit By Drownings which will-be held in Texas in July. Eight of the ten girls already had sponsors but the club's two- ' — Story On Pagt 2 fastest sprinters were sponsorlcss until the Merry Makers came to the rescue. The two young ladies are Miss Rita Thompson, 689 S. Cham- pion av., and Miss Dolores Moore, 141 E. 8th av. • LAST SATURDAY In Cleveland, Rita ran the 75 yard dash • in 8.7 seconds, which is within three tenths of a second of the American record for women. She is a senior at Central High love End In school. Dolores is a sophomore at Sacred Heart. Both girls run an chor on their respective relay teams. ,. ' ' Story On Page 2 While it is fantastic tp hopa that the girls can defeat Tennes see State's great sprinter, we can hope and pray that they can be * good enough to make the squad. -

The Sentinel UUP — Oneonta Local 2190

The Sentinel UUP — Oneonta Local 2190 Volume 11, Number 6 February 2011 Using SPI or SRFI to Compare Faculty Teaching Effectiveness: Is it Statistically Appropriate? By Jen-Ting Wang, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Statistics, De- partment of Mathematics, Computer Science, and Statistics Backgrounds and Problems of Faculty Evaluation through SRFI For the past few months, the new instrument for measuring teaching effec- tiveness known as SRFI (Student Response to Faculty Instruction), has been widely discussed among faculty members on campus and implemented in the Senate. After reviewing some of the available documents, I am compelled to address some concerns about the proposed instrument. As a statistician with a Ph.D. in Statistics and over 10 years of experience teaching and consulting in Statistics, I'd like to express my concerns regarding SRFI from the statistical point of view. When the SPI was first implemented on campus over 20 years ago, the main purpose was to provide faculty with feedback on their teaching. It was not to be incorporated into the evaluation of faculty teaching for re- appointment, tenure, promotion, or DSI. For some reason, it has now become one of the most important assess- ment tools, if not the primary one, for evaluating teaching effectiveness. Furthermore, teaching effectiveness is often reduced to only one number -- the mean score, which has been mistakenly used for comparative analyses of faculty members’ teaching effectiveness. It is also often being misinterpreted that, for example, one faculty mem- ber with an overall mean score of 3.8 has better teaching effectiveness than another faculty member with 3.7. -

Statues and Figurines

NEW STATUES! 1. The Thing Premium Format 550.00 2. Thor Premium Format 900.00 3. Hulk Premium Format 1500.00 4. Art Asylum Hulk 299.00 5. Juggernaut 450.00 6. Wolverine vs Sabretooth 699.00 7. Ironman Comiquette 449.00 8. Mark Newman Sabretooth 245.00 9. Planet Hulk Green Scar vs Silver Savage 500.00 10. Bowen Retro Green Hulk 279.99 11. Moonlight Silver 299.99 12. Hulk Planet Hulk Version 299.99 13. X-Men vs Sentinel 249.99 14. Red Hulk 225.99 15. Art Asylum Captain America 199.00 16. Kotobukiya Ltd Ed. Hulk 225.00 17. Kotobukiya Ltd Ed. Abomination 200.00 18. Bowen Wolverine Action 249.99 19. Sgt Rock 89.99 20. Bowen Shiflet Bros Hulk 299.00 21. Hulk Hard Hero 229.00 22. Superman 199.99 23. Wolverine Diorama 169.99 24. Dead pool 275.00 25. Dead pool 275.00 26. Wolverine with Whiskey 150.00 27. Hulk Marvel Origins 139.00 28. Captain America Resin Bank 24.99 29. Hulk Fine Art Bust 99.99 30. Captain America Mini Bust 89.99 31. Flash vs Gorilla Grodd 200.00 32. Bishoujo Batgirl 59.99 33. Harley Quinn 90.00 34. Swamp Thing 95.00 35. Flaming Carrot 229.99 36. Death 99.99 37. Sandman 99.99 38. BW Batman 79.99 39. ONI Chan 40.00 40. Umbrella Acsdemy 129.99 41. Lord Of The Rings 129.99 42. Silver Surfer 150.00 43. X-Men Origins Wolverine Bust Only 39.99 44. X-Men Origins Wolverine Bust Bluray 80.00 45. -

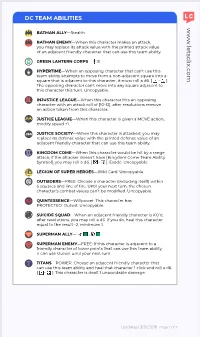

W W W .Letsc Lix.C Om

DC TEAM ABILITIES www.letsclix.com BATMAN ALLY—Stealth. BATMAN ENEMY—When this character makes an attack, you may replace its attack value with the printed attack value of an adjacent friendly character that can use this team ability. GREEN LANTERN CORPS— :8. HYPERTIME—When an opposing character that can’t use this team ability attempts to move from a non-adjacent square into a square that is adjacent to this character, it must roll a d6. [ - ]: The opposing character can’t move into any square adjacent to this character this turn. Uncopyable. INJUSTICE LEAGUE—When this character hits an opposing character with an attack roll of [10-12], after resolutions remove an action token from this character. JUSTICE LEAGUE—When this character is given a MOVE action, modify speed +1. JUSTICE SOCIETY—When this character is attacked, you may replace its defense value with the printed defense value of an adjacent friendly character that can use this team ability. KINGDOM COME—When this character would be hit by a range attack, if the attacker doesn’t have [Kingdom Come Team Ability Symbol], you may roll a d6. [ - ]: Evade. Uncopyable. LEGION OF SUPER HEROES—Wild Card. Uncopyable. OUTSIDERS—FREE: Choose a character (including itself) within 6 squares and line of fire. Until your next turn, the chosen character’s combat values can’t be modified. Uncopyable. QUINTESSENCE—Willpower. This character has PROTECTED: Outwit. Uncopyable. SUICIDE SQUAD—When an adjacent friendly character is KO’d, after resolutions, you may roll a d6. If you do, heal this character equal to the result -2, minimum 1. -

Marvel Comics Proudly Presents…

MARVEL COMICS PROUDLY PRESENTS… Long ago, Greg Salinger was the Foolkiller, a vigilante targeting perpetrators of foolish crimes. He was one of Deadpool’s Mercs for Money, but left to try a normal life as a S.H.I.E.L.D. psychologist, treating former costumed criminals. He had an apartment, a girlfriend, a trusted boss, but couldn’t psychoanalyze so many fools without killing a few. While Greg wrestled with guilt, Kurt Gerhardt, the maniac who took on the Foolkiller mantle when Greg was inactive, began sabotaging Greg’s new life. He revealed Greg’s girlfriend was once involved in a foolish crime, then confronted Greg in his office with the information that his boss was using him as an unwilling hit man. At his wit’s end, Greg shot and smashed his way out… Writer MAX BEMIS Penciler DALIBOR TALAJIĆ Inker JOSÉ MARZAN JR. Colors MIROSLAV MRVA Lettering VC’S TRAVIS LANHAM Cover DAVE JOHNSON Assistant Editor KATHLEEN WISNESKI Editor DARREN SHAN Consulting Editor JORDAN D. WHITE Editor in Chief AXEL ALONSO Chief Creative Officer JOE QUESADA Publisher DAN BUCKLEY Executive Producer ALAN FINE FOOLKILLER No. 4, April 2017. Published Monthly by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. BULK MAIL POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK, NY AND AT ADDITIONAL MAILING OFFICES. © 2017 MARVEL No similarity between any of the names, characters, persons, and/or institutions in this magazine with those of any living or dead person or institution is intended, and any such similarity which may exist is purely coincidental. -

Rationale for Magneto: Testament Brian Kelley

SANE journal: Sequential Art Narrative in Education Volume 1 Article 7 Issue 1 Comics in the Contact Zone 1-1-2010 Rationale For Magneto: Testament Brian Kelley Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sane Part of the American Literature Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Art Education Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Educational Psychology Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Higher Education Commons, Illustration Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kelley, Brian (2010) "Rationale For Magneto: Testament," SANE journal: Sequential Art Narrative in Education: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 7. Available at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sane/vol1/iss1/7 This Rationale is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in SANE journal: Sequential Art Narrative in Education by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Kelley: Rationale For Magneto: Testament 1:1_______________________________________r7 X-Men: Magneto Testament (2009) By Gregory Pak and Carmine Di Giandomenico Rationale by Brian Kelley Grade Level and Audience This graphic novel is recommended for middle and high school English and social studies classes. Plot Summary Before there was the complex X-Men villain Mangeto, there was Max Eisenhardt. As a boy, Max has a loving family: a father who tinkers with jewelry, an overprotective mother, a sickly sister, and an uncle determined to teach him how to be a ladies’ man. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership.