Music Via Correspondence: a List of the Music Collection of Dresden Kreuzorganist Emanuel Benisch*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jan Dismas Zelenka's Missae Ultimae

Jan Dismas Zelenka's Missa Dei Patris (1740): The Use of stile misto in Missa Dei Patris (ZWV 19) Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Cho, Hyunjin Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 20:42:28 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195489 JAN DISMAS ZELENKA‟S MISSA DEI PATRIS (1740): THE USE OF STILE MISTO IN MISSA DEI PATRIS (ZWV 19) by HyunJin Cho ______________________ Copyright © HyunJin Cho 2010 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2010 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by HyunJin Cho entitled Jan Dismas Zelenka‟s Missa Dei Patris (1740): The Use of stile misto in Missa Dei Patris (ZWV 19) and recommend that it be accepted as the fulfilling requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts ___________________________________________________ Date: 07/16/2010 Bruce Chamberlain ___________________________________________________ Date: 07/16/2010 Elizabeth Schauer ___________________________________________________ Date: 07/16/2010 Robert Bayless Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate‟s submission of the final copy of the document to the Graduate College. -

Apollo's Fire

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Saturday, November 9, 2013, 8pm Johann David Heinichen (1683–1789) Selections from Concerto Grosso in G major, First Congregational Church SeiH 213 Entrée — Loure Menuet & L’A ir à L’Ita lien Apollo’s Fire The Cleveland Baroque Orchestra Heinichen Concerto Grosso in C major, SeiH 211 Jeannette Sorrell, Music Director Allegro — Pastorell — Adagio — Allegro assai Francis Colpron, recorder Kathie Stewart, traverso PROGRAM Debra Nagy, oboe Olivier Brault, violin Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) “Brandenburg” Concerto No. 3 in G major, BWV 1048 Bach “Brandenburg” Concerto No. 4 in G major, BWV 1049 Allegro — Adagio — Allegro Allegro — Andante — Presto Olivier Brault, violin Bach “Brandenburg” Concerto No. 5 in D major, Francis Colpron & Kathie Stewart, recorders BWV 1050 Allegro Affettuoso The Apollo’s Fire national tour of the “Brandenburg” Concertos is made possible by Allegro a generous grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Jeannette Sorrell, harpsichord Apollo’s Fire’s CDs, including the complete “Brandenburg” Concertos, are for sale in the lobby. Olivier Brault, violin The artists will be on hand to sign CDs following the concert. Kathie Stewart, traverso INTERMISSION Cal Performances’ 2013–2014 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 16 CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES 17 PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES a mountaintop experience: extraordinary power to move, delight, and cap- Concerto No. 5 requires from the harpsi- performing concertos for the virtuoso bands of europe tivate audiences for 250 years. But what is it that chordist a level of speed in the scalar passages gives them that power—that greatness that we that far exceeds anything else in the repertoire. -

Die Rezeption Der Alten Musik in München Zwischen Ca

Studienabschlussarbeiten Fakultät für Geschichts- und Kunstwissenschaften Grill, Tobias: Die Rezeption der Alten Musik in München zwischen ca. 1880 und 1930 Magisterarbeit, 2007 Gutachter: Rathert, Wolfgang Fakultät für Geschichts- und Kunstwissenschaften Department Kunstwissenschaften Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.6795 Die Rezeption der Alten Musik in München zwischen ca. 1880 und 1930 Abschlussarbeit zur Erlangung des Grades eines Magister Artium im Fach Musikwissenschaft an der Fakultät für Geschichts- und Kunstwissenschaften der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Eingereicht bei: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Rathert Vorgelegt von: Tobias Grill Oktober 2007 Inhalt Seite I. Einleitung .............................................................................................................................5 II. Einführung und Überblick zum beginnenden theoretischen und praktischen Interesse an Alter Musik und ihrer Aufführung.............................................................7 1. Begriff „Alte Musik“ .................................................................................................................7 2. Historismus ...............................................................................................................................10 3. Überblick ..................................................................................................................................13 3.1 Aufführungspraxis ..............................................................................................................13 -

Johann Kaspar Kerll Missa Non Sine Quare

Johann Kaspar Kerll Missa non sine quare La Risonanza Fabio Bonizzoni La Risonanza Elisa Franzetti soprano Emanuele Bianchi countertenor Mario Cecchetti tenor Sergio Foresti bass Carla Marotta, David Plantier violin Peter Birner cornett Olaf Reimers violoncello Giorgio Sanvito violone Ivan Pelà theorbo Fabio Bonizzoni organ & direction Recording: May 1999, Chiesa di San Lorenzo, Laino (Italy) Recording producer: Sigrid Lee & Roberto Meo Booklet editor & layout: Joachim Berenbold Artist photo (p 2): Marco Borggreve Translations: Peter Weber (deutsch), Sigrid Lee (English), Nina Bernfeld (français) π 1999 © 2021 note 1 music gmbh Johann Kaspar Kerll (1627-1693) Missa non sine quare 1 Introitus Cibavit eos (gregorian) 1:03 2 Kyrie, Christe, Kyrie * 3:31 3 Gloria * 4:49 4 Graduale Sonata in F major for two violins & b.c. 6:32 5 Credo * 7:15 6 Offertorium Plaudentes Virgini for soprano, alto, tenor, bass & b.c. 3:45 7 Sanctus et Benedictus * 4:17 8 Agnus Dei * 2:18 9 Communio Ama cor meum for alto, tenor, two violins & b.c. 7:25 10 Dignare me for soprano, alto, bass & b.c. 2:34 11 Post Communio Sonata in G minor for two violins, bass & b.c. 7:13 12 Deo Gratias Regina caeli laetare 2:31 * from Missa non sine quare English English cent coronation of the new Austrian Emperor various instruments (violins, violas, trombones) incomplete copy (only 10 of 19 parts remain- Leopold in Frankfurt, in the summer of 1658, and continuo. This type of concerted mass was ing) belongs to the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Johann Kaspar Kerll Kerll composed a mass and was invited to play widely used for important liturgical occasions in of Munich along with a manuscript score (a the organ during the ceremony. -

Dresden Eng 03

Music City Dresden Program # 3 „Gloria in Excelsis Deo“: A Century of Catholic Church Music at the Dresden Court Greetings from Bonn, Germany, for another program on the musical heritage of the city of Dresden. I’m Michael Rothe. It has taken sixty years for the Frauenkirche, the Church of Our Lady, to rise in new splendor from the rubble and ashes into which it sank during the infamous firebombing that consumed the entire city in February of 1945. 2005 is the year of the rededication of that glorious landmark, and we mark the occasion with this broadcast series from Deutsche Welle Radio, “Music City Dresden.“ Today we’ll survey a century of Catholic church music at the Dresden court, and we begin with this movement from an early 18th century setting of the Magnificat by Johann David Heinichen. Johann David Heinichen (1683-1729) Magnificat in A Major: 6th movement: Sicut erat in principio 1:50 Rheinische Kantorei, Das kleine Konzert Cond: Hermann Max LC 08748, Capriccio 10 557, (Track 20) The region ruled by the Saxon princes from the seat of their court in Dresden had long been Protestant. But around the turn of the 18th century, Catholicism found its way into the city, quietly, as if on tiptoes. That all had very much to do with the Saxon Elector Frederick Augustus I, who came to be known as Augustus the Strong. Augustus converted to Roman Catholicism in 1697. His entire family soon followed course. For the popular sovereign, who had a reputation as something of a skirt-chaser, it wasn’t a matter of religious fervor, but power politics. -

The Sources of the Christmas Interpolations in J. S. Bach's Magnificat in E-Flat Major (BWV 243A)*

The Sources of the Christmas Interpolations in J. S. Bach's Magnificat in E-flat Major (BWV 243a)* By Robert M. Cammarota Apart from changes in tonality and instrumentation, the two versions of J. S. Bach's Magnificat differ from each other mainly in the presence offour Christmas interpolations in the earlier E-flat major setting (BWV 243a).' These include newly composed settings of the first strophe of Luther's lied "Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her" (1539); the last four verses of "Freut euch und jubiliert," a celebrated lied whose origin is unknown; "Gloria in excelsis Deo" (Luke 2:14); and the last four verses and Alleluia of "Virga Jesse floruit," attributed to Paul Eber (1570).2 The custom of troping the Magnificat at vespers on major feasts, particu larly Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost, was cultivated in German-speaking lands of central and eastern Europe from the 14th through the 17th centu ries; it continued to be observed in Leipzig during the first quarter of the 18th century. The procedure involved the interpolation of hymns and popu lar songs (lieder) appropriate to the feast into a polyphonic or, later, a con certed setting of the Magnificat. The texts of these interpolations were in Latin, German, or macaronic Latin-German. Although the origin oftroping the Magnificat is unknown, the practice has been traced back to the mid-14th century. The earliest examples of Magnifi cat tropes occur in the Seckauer Cantional of 1345.' These include "Magnifi cat Pater ingenitus a quo sunt omnia" and "Magnificat Stella nova radiat. "4 Both are designated for the Feast of the Nativity.' The tropes to the Magnificat were known by different names during the 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries. -

Document Cover Page

A Conductor’s Guide and a New Edition of Christoph Graupner's Wo Gehet Jesus Hin?, GWV 1119/39 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Seal, Kevin Michael Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 06:03:50 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/645781 A CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE AND A NEW EDITION OF CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER'S WO GEHET JESUS HIN?, GWV 1119/39 by Kevin M. Seal __________________________ Copyright © Kevin M. Seal 2020 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Doctor of Musical Arts Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by: Kevin Michael Seal titled: A CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE AND A NEW EDITION OF CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER'S WO GEHET JESUS HIN, GWV 1119/39 and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Bruce Chamberlain _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 7, 2020 Bruce Chamberlain _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 3, 2020 John T Brobeck _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 7, 2020 Rex A. Woods Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

Program Booklet 2007

27th Annual Season 17-24 June 2007 2 Los Angeles • Century City • San Francisco • Orange County • Del Mar Heights San Diego • Santa Barbara • New York • Washington D. C. • Shanghai 3 4 May 20 – August 26, 2007 850 San Clemente Drive | Newport Beach Mary Heilmann: To Be Someone is sponsored by: Major support for the exhibition is provided by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency. The official media sponsor of the Orange County Museum of Art is: nt0670_BMF_4.75x3.75 5/4/07 4:15 PM Page 1 www.ocma.net Additional media sponsorship is provided by: It may be those who do most, dream most. — STEPHEN LEACOCK Northern Trust salutes those whose dreams have broadened our horizons, brightened our worlds, and helped make the Baroque Music Festival a success. Betty Mower Potalivo, Region President – Orange County and Desert Communities 16 Corporate Plaza Drive, Newport Beach, CA 92660 • 949-717-5506 northerntrust.com Northern Trust Banks are members FDIC. ©2007 Northern Trust Corporation. 5 What is Your NUMBER? What is Your NUMBER? [How many dollars will you [How many dollars will you need to produce the need to produce the retirement retirement income you want?] income you want?] Call us for a complimentary initial consultation to Call us for a complimentary initial consultation to explore this question explore this question and many others, including “how?” and many others, including “how?” The Lindbloom Powell Group specializes in helping The Lindbloom Powell Group specializes in helping clients convert clients convert wealth to income in retirement. -

Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis

Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis All BWV (All data), numerical order Print: 25 January, 1997 To be BWV Title Subtitle & Notes Strength placed after 1 Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern Kantate am Fest Mariae Verkündigung (Festo annuntiationis Soli: S, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Corno I, II; Ob. da Mariae) caccia I, II; Viol. conc. I, II; Viol. rip. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 2 Ach Gott, von Himmel sieh darein Kantate am zweiten Sonntag nach Trinitatis (Dominica 2 post Soli: A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Tromb. I - IV; Ob. I, II; Trinitatis) Viol. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 3 Ach Gott, wie manches Herzeleid Kantate am zweiten Sonntag nach Epiphanias (Dominica 2 Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Corno; Tromb.; Ob. post Epiphanias) d'amore I, II; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 4 Christ lag in Todes Banden Kantate am Osterfest (Feria Paschatos) Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Cornetto; Tromb. I, II, III; Viol. I, II; Vla. I, II; Cont. 5 Wo soll ich fliehen hin Kantate am 19. Sonntag nach Trinitatis (Dominica 19 post Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Tromba da tirarsi; Trinitatis) Ob. I, II; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Vcl. (Vcl. picc.?); Cont. 6 Bleib bei uns, denn es will Abend werden Kantate am zweiten Osterfesttag (Feria 2 Paschatos) Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Ob. I, II; Ob. da caccia; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Vcl. picc. (Viola pomposa); Cont. 7 Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam Kantate am Fest Johannis des Taüfers (Festo S. -

Harald Vogel

Westfield Center & Christ Church Cathedral present Harald Vogel Johann Caspar Kerll (1627-1693) Toccata per li Pedali Canzon in d Bataglia Capriccio Cucu Johann Pachelbel (1653-1706) Praeludium in d Toccata in e Georg Böhm (1661-1733) Ach wie nichtig, ach wie flüchtig Partita 1 Grand Plein-Jeu Partita 2 Dessus de Cromorne Partita 3 Dessus de Nazard Partita 4 Basse de Trompette Partita 5 Trio Partita 6 Voix humaine Partita 7 Grand-Jeux (dialogue) Partita 8 Flutes Partita 9 Petit Plein-Jeu Johann Kuhnau (1660-1722) Toccata in A-Dur Sauls Traurigkeit und Unsinnigkeit (Saul’s Sadness and Craziness) La tristezza ed il furore del Rè -aus der zweiten Biblischen Sonate: Der von David vermittelst der Music curierte Saul Saul malincolico e trastullato per mezzo della Musica Mr. Vogel’s appearance is sponsored by Loft Recordings J.S. Bach Praeludium in g minor (BWV 535a) O Lamm Gottes unschuldig (BWV 656), from the Leipzig chorales 3 Verses Praeludium und Fuge in D-Dur (BWV 532) Praeludium - Erde (earth) Fuge - Wasser (water) _____ The Central/Southern European influences on J.S. Bach are focused strongly on the style of Johann Pachelbel and his school. The elder brother, Johann Christoph Bach, who gave the 10 year old Johann Sebastian a new home in Ohrdruf (Thuringia) after the death of their parents, was a student of Pachelbel. Pachelbel was a good friend of Johann Ambrosius, the father of Johann Sebastian. The early works of Johann Sebastian strongly show the Pachelbel models in figuration (“der figurirte Stil”) and counterpoint. The organ works of Johann Pachelbel show the influence of Johann Caspar Kerll, who studied in Rome and where he acquired the new expressive organ style of Frescobaldi and his followers. -

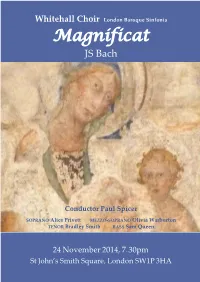

Magnificat JS Bach

Whitehall Choir London Baroque Sinfonia Magnificat JS Bach Conductor Paul Spicer SOPRANO Alice Privett MEZZO-SOPRANO Olivia Warburton TENOR Bradley Smith BASS Sam Queen 24 November 2014, 7. 30pm St John’s Smith Square, London SW1P 3HA In accordance with the requirements of Westminster City Council persons shall not be permitted to sit or stand in any gangway. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment is strictly forbidden without formal consent from St John’s. Smoking is not permitted anywhere in St John’s. Refreshments are permitted only in the restaurant in the Crypt. Please ensure that all digital watch alarms, pagers and mobile phones are switched off. During the interval and after the concert the restaurant is open for licensed refreshments. Box Office Tel: 020 7222 1061 www.sjss.org.uk/ St John’s Smith Square Charitable Trust, registered charity no: 1045390. Registered in England. Company no: 3028678. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Choir is very grateful for the support it continues to receive from the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS). The Choir would like to thank Philip Pratley, the Concert Manager, and all tonight’s volunteer helpers. We are grateful to Hertfordshire Libraries’ Performing Arts service for the supply of hire music used in this concert. The image on the front of the programme is from a photograph taken by choir member Ruth Eastman of the Madonna fresco in the Papal Palace in Avignon. WHITEHALL CHOIR - FORTHCOMING EVENTS (For further details visit www.whitehallchoir.org.uk.) Tuesday, 16 -

Requiem Aeternam –Terequiem Aeternam –Requiem Aeternam Decethymnus ( Domine Jesu –Quam Olim –Sedsignifer Abrahae Christe

MENU — TRACKLIST P. 4 ENGLISH P. 8 FRANÇAIS P. 14 DEUTSCH P. 20 SUNG TEXTS P. 28 Th is recording has been made with the support of the Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles (Direction générale de la Culture, Service de la Musique) Recording 2 Kerll: Beaufays, église Saint-Jean-Baptiste, November 2015 Fux: Stavelot, église Saint-Sébastien, October 2015 Artistic direction, recording & editing: Jérôme Lejeune Cover illustration Johann Gottfried Auerbach (1697-1753) Portrait of Emperor Karl VI Wien, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Photo:© akg-images/ Nemeth Our thanks to the staff of the Festival de Stavelot for their invaluable assistance in organising the use of the church of Saint-Sébastien for this recording. JOHANN CASPAR KERLL 16271693 JOHANN JOSEPH FUX 16601741 3 REQUIEMS — VOX LUMINIS SCORPIO COLLECTIEF (Simen van Mechelen) L‘ACHÉRON (François Joubert-Caillet) Lionel Meunier: artistic director Missa pro defunctis Johann Caspar Kerll TEXTS 01. Introitus (Requiem aeternam – Te decet hymnus – Requiem aeternam) 5’26 02. Kyrie 2’02 DE SUNG 03. Sequenza 13’34 FR Dies Irae dies illa (coro) Quantus tremor (bassus) Tuba mirum (tenor) Mors stupebit (altus) MENU EN Liber scriptus – Judex ergo (coro) 4 Quid sum miser – Rex tremendae (cantus) Recordare Jesu pie (tenor) Quaerens me (tenor) Juste Judex-Ingemisco (coro) Quid Mariam absolvisti (altus, tenor, bassus) Inter oves (cantus, altus) Confutatis maledictis (bassus) Oro suplex (coro) Lacrimosa dies illa (cantus) Huic ergo – Pie Jesu (coro) 04. Off ertorium (Domine Jesu Christe – Sed signifer – Quam olim Abrahae) 3’57 05. Sanctus – Beneditus – Hosanna 4’27 06. Agnus Dei 2’34 07. Communio (Lux aeterna) 2’44 VOX LUMINIS Sara Jäggi & Zsuzsi Tóth: sopranos Barnabás Hegyi & Jan Kullmann: countertenors 5 Philippe Froeliger & Dávid Szigetvári: tenors I Olivier Berten & Robert Buckland: tenors II Matthias Lutze & Lionel Meunier: basses Bart Jacobs: organ L’ACHÉRON François Joubert-Caillet: treble viol Marie-Suzanne de Loye: tenor viol Andreas Linos: bass viol Lucile Boulanger: consort bass viol Kaiserrequiem Johann Joseph Fux 08.