Theories of Crime and Deviance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Meaning of Cultural Criminology August, 2015, Vol 7(2): 34-48 L

Journal of Theoretical & Philosophical Criminology The meaning of cultural criminology August, 2015, Vol 7(2): 34-48 L. Bevier _______________________________________ July, 2015, 7, 34-48 _______________________________________ The Meaning of Cultural Criminology: A Theoretical and Methodological Lineage Landon Bevier, University of Tennessee _______________________________________ Abstract The field of cultural criminology has faced much criticism concerning the perspective's perceived theoretical ambiguity and inadequate definition of its core concept: culture (O’Brien, 2005; Webber, 2007). One critique goes so far as to conclude by asking, "One has to wonder, what is cultural criminology?" (Spencer, 2010, p. 21) In the current paper, I endeavor to answer this question using the theoretical texts of cultural criminology. Whereas critics use cultural criminologists’ “own words” to evidence a lack of clarity (Farrell, 2010, p. 60), I use such words to clarify the logic, scope, and meaning of cultural criminology. In so doing, I explore the role of cultural criminology as a subfield of academic criminology; examine prior conceptualizations of 'culture' and their relation to that of cultural criminology, and trace the main methodological and theoretical antecedents from which the field emerged. ______________________________________ 34 Journal of Theoretical & Philosophical Criminology The meaning of cultural criminology August, 2015, Vol 7(2): 34-48 L. Bevier The Meaning of Cultural Criminology: A Theoretical and Methodological Lineage The field of cultural criminology has "borne many slings and arrows, more so than almost any other of the critical criminologies in the last few years" (Muzzatti, 2006, p. 74). Many such slings and arrows are aimed at the perspective's perceived theoretical ambiguity and inadequate definition of its core concept: culture (O’Brien, 2005; Webber, 2007; Farrell, 2010; Spencer, 2010). -

Social Structure, Culture, and Crime: Assessing Kornhauser’S Challenge to Criminology1

6 Social Structure, Culture, and Crime: Assessing Kornhauser’s Challenge to Criminology1 Ross L. Matsueda Ruth Kornhauser’s (1978) Social Sources of Delinquency has had a lasting infl uence on criminological theory and research. This infl uence consists of three contributions. First, Kornhauser (1978) developed a typology of criminological theories—using labels social disorganization, control, strain, and cultural devi- ance theories—that persists today. She distinguished perspectives by assump- tions about social order, motivation, determinism, and level of explanation, as well as by implications for causal models of delinquency. Second, Kornhauser addressed fundamental sociological concepts, including social structure, culture, and social situations, and provided a critical evaluation of their use within differ- ent theoretical perspectives. Third, she helped foster a resurgence of interest in social control and social disorganization theories of crime (e.g., Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990; Hirschi 1969; Sampson and Laub 1993; Bursik and Webb 1982; Kubrin and Weitzer 2003; Sampson and Groves 1989), both indirectly via the infl uence of an early version of the manuscript that would become Social Sources (see Chapter 3 in this volume) on Hirschi’s (1969) Causes of Delinquency , and directly via the infl uence of her book on the revitalization of social disorgani- zation theories of crime. Kornhauser’s infl uence on the writings of Hirschi, Bursik, and Sampson was particularly signifi cant and positive, as control and disorganization theo- ries came to dominate the discipline, stimulating a large body of research that increased our understanding of conventional institutional control of crime and delinquency through community organization, family life, and school effects. -

D:\Full Dissertation\Golden Goal.Wpd

Modern English Football Hooliganism: A Quantitative Exploration in Criminological Theory Rich A. Wallace Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology Carol A. Bailey, Co-Chair William E. Snizek, Co-Chair Clifton D. Bryant Charles J. Dudley Donald J. Shoemaker December 10, 1998 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Football Hooliganism, Criminology, Theory, Subcultural Delinquency Copyright 1998, Rich A. Wallace Modern English Football Hooliganism: A Quantitative Exploration in Criminological Theory Rich A. Wallace (ABSTRACT) Studies of football hooliganism have developed in a number of academic disciplines, yet little of this literature directly relates to criminology. The fighting, disorderly conduct, and destructive behavior of those who attend football matches, especially in Europe has blossomed over the past thirty years and deserves criminological attention. Football hooliganism is criminal activity, but is unique because of its context specific nature, occurring almost entirely inside the grounds or in proximity to the stadiums where the matches are played. This project explores the need for criminological explanations of football hooligans and their behavior based on literature which indicates that subcultural theories may be valuable in understanding why this behavioral pattern has become a preserve for young, white, working-class males. This study employs Albert Cohen’s (1955) theory of subcultural delinquency to predict the hooligan activities of young, white, working-class males. West and Farrington’s longitudinal study, the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development provides a wealth of data on numerous topics, including hooliganism, and is used to explore the link between hooliganism and criminological theory. -

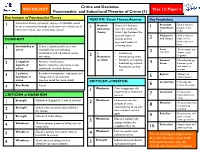

Functionalist and Subcultural Theories of Crime (1) Year 13: Paper 3

Crime and Deviance- SOCIOLOGY Year 13: Paper 3 Functionalist and Subcultural Theories of Crime (1) Key features of Functionalist Theory MERTON- Strain Theory:Anomie Key Vocabulary Consensus theory, structural, society vs individual, social 1 Boundary Crime reminds order is maintained through socialisation of a shared set of Anomie Crime and deviance 1 1 and strain were the result of a maintenanc people of the norms and values- the central value system. e rules theory strain / gap between the approved goals of Adaptation Crime helps us DURKHEIM society and the 2 and change improve the approved means of law/create new laws Inevitability of Crime is dysfunctional but is also achieving them. 1 crime inevitable-due to inadequate Social Communities are socialisation and subcultural norms 5 • Conformity 3 cohesion drawn closer and values. 2 Responses • Innovation eg crime together to strain • Ritualism eg coasting 2 negative Anomie- normlessness Anomie/ Normlessnes-gap • Rebellion eg activism 4 Strain between goals 2 aspects of Egoism-collective conscience is too • Retreatism eg drop and means of crime weak-leads to selfish desires. out success 3 3 positive Boundary maintenance, adaptation and Egoism Giving in to functions of change and social cohesion 5 selfish desires crime (see key vocab for more detail) CRITICISM of MERTON Conformity Following the Key Study Suicide 6 norms of society 4 Weakness Over exaggerates the 1 importance of monetary Innovation Accept goals, CRITICISM of DURKHEIM success. 7 reject means eg crime 1 Strength Newburn-Suggests crime is normal 2 Weakness Underestimates the amount of crime 8 Ritualism Accept means but committed by those who not goals eg Strength Linked crime to social values-allowed coasting 2 for change have achieved societal goals. -

Race and Anomie: a Comparison of Crime Among Rural Whites and Urban Blacks Based on Social Structural Conditions

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2011 Race and Anomie: A Comparison of Crime Among Rural Whites and Urban Blacks Based on Social Structural Conditions. Mical Dominique Carter East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Criminology Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Carter, Mical Dominique, "Race and Anomie: A Comparison of Crime Among Rural Whites and Urban Blacks Based on Social Structural Conditions." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1305. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1305 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Race and Anomie: A Comparison of Crime Among Rural Whites and Urban Blacks Based on Social Structural Conditions _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Criminal Justice & Criminology East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Criminal Justice & Criminology _____________________ by Mical Dominique Carter May 2011 _____________________ Larry Miller, Ph.D., Chair Nicole Prior, Ph.D. John T. Whitehead Ph.D. Keywords: Anomie, Rural Crime, Urban Crime, Race and Crime ABSTRACT Race and Anomie: A Comparison of Crime Among Rural Whites and Urban Blacks Based on Social Structural Conditions by Mical Dominique Carter This study examined the relationship between social structures and crime among rural white and urban black males in North Carolina through the theoretical framework of Merton’s Anomie. -

Rethinking Subculture and Subcultural Theory in the Study of Youth Crime – a Theoretical Discourse Chijioke J

Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Criminology Rethinking Subculture & Subcultural Theory January 2015, Vol. 7: 1-16 Nwalozie Journal of Theoretical & Philosophical Criminology ISSN: 2166-8094 JTPCRIM, July 2015, 7: 1-16 _______________________________________ Rethinking Subculture and Subcultural Theory in the Study of Youth Crime – A Theoretical Discourse Chijioke J. Nwalozie, New College, Stamford, U.K. _______________________________________ Abstract Subcultural theory is an invention of the Anglo-American sociologists and criminologists of the 1960s and 1970s. They chiefly refer to male urban working class youths whose behaviours are contrary to the dominant society. These youths are usually culturally identified with music, dress code, tattoo, and language. Whereas, it is assumed that subculture refers to lower subordinate or dominant status of social group labelled as such, yet, in societies where the Anglo/American cultural identities are wanting, it becomes difficult to recognise such deviant group of youths as subculture. This paper argues there should be a rethink about “subculture” and “subcultural theory”. The rethink must ensure that youth subcultures are not benchmarked by those Anglo/American cultural identities, but should in the main refer to youths whose behaviours are oppositional to the mainstream culture, irrespective of the societies they come from. 1 Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Criminology Rethinking Subculture & Subcultural Theory January 2015, Vol. 7: 1-16 Nwalozie Meaning of subculture(s) One of the assumptions about “subculture” is the lower, subordinate, or deviant status of social groups labelled as such. These labelled groupings are distinguished by their class, ethnicity, language, poor and working class situations (Cutler, 2006); age or generation (Maira, 1999). -

Theories and Causes of Crime

Theories and causes of crime Introduction There is no one ‘cause’ of crime. Crime is a highly complex phenomenon that changes across cultures and across time. Activities that are legal in one country (e.g. alcohol consumption in the UK) are sometimes illegal in others (e.g. strict Muslim countries). As cultures change over time, behaviours that once were not criminalised may become criminalised (and then decriminalised again – e.g. alcohol prohibition in the USA). As a result, there is no simple answer to the question ‘what is crime?’ and therefore no single answer to ‘what causes crime?’ Different types of crime often have their own distinct causes. (For more about definitions of crime see SCCJR What is Crime? You can also find out about specific types of crime at: SCCJR Violence Against Women and Girls; SCCJR Drug Crime; SCCJR Knife Crime) This briefing provides an overview of some of the key criminological theories that seek to explain the causes of crime; it is by no means an exhaustive list. Each of the theories covered has its own strengths and weaknesses, has gaps and may only be applicable to certain types of crime, and not others. There is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ theory. The theories covered can be categorised into two main approaches: 1) Biological theories 2) Sociological theories 1 1) Biological theories Biological explanations of crime assume that some people are ‘born criminals’, who are physiologically distinct from non-criminals. The most famous proponent of this approach is Cesare Lombroso. Lombroso and Biological Positivism In the 19th Century, Italian prison psychiatrist Cesare Lombroso drew on the ideas of Charles Darwin and suggested that criminals were atavistic: essentially ‘evolutionary throwbacks’. -

Cultural Criminology: Some Notes on the Script

CULTURAL CRIMINOLOGY: SOME NOTES ON THE SCRIPT By Keith Hayward and Jock Young [Source: Special edition of the international journal Theoretical Criminology, Volume 8 No 3 pp. 259-285] Introduction Let us start with a question: what is this phenomenon called ‘cultural criminology’? Above all else, it is the placing of crime and its control in the context of culture; that is, viewing both crime and the agencies of control as cultural products - as creative constructs. As such they must be read in terms of the meanings they carry. Furthermore, cultural criminology seeks to highlight the interaction between these two elements: the relationship and the interaction between constructions upwards and constructions downwards. Its focus is always upon the continuous generation of meaning around interaction; rules created, rules broken, a constant interplay of moral entrepreneurship, moral innovation and transgression. Going further still, it strives to place this interplay deep within the vast proliferation of media images of crime and deviance, where every facet of offending is reflected in a vast hall of mirrors (see Ferrell, 1999). It attempts to make sense of a world in which the street scripts the screen and the screen scripts the street. Here there is no linear sequence, rather the line between the real and the virtual is profoundly and irrevocably blurred. All of these attributes: the cultural nature of crime and control, their interaction in an interplay of constructions, and the mediation through fact and fiction, news and literature, have occurred throughout history and are thus a necessary basis for any criminology which claims to be ‘naturalistic’. -

The Evolution of Criminological Theories

THE EVOLUTION OF CRIMINOLOGICAL THEORIES by Jonathon M. Heidt B.A., University of Montana, 2000 M.A., Simon Fraser University, 2004 DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the School of Criminology Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Jonathon Heidt 2011 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2011 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for "Fair Dealing." Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Jonathon Heidt Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis: The Evolution of Criminological Theories Examining Committee: Chair: William Glackman, PhD Associate Professor _______________________________________________ Robert M. Gordon, PhD Senior Supervisor Director, School of Criminology _______________________________________________ Brian Burtch, PhD Supervisor Professor _______________________________________________ Eric Beauregard, PhD Supervisor Associate Professor _______________________________________________ Stephen D. Hart, PhD Internal Examiner Professor Department of Psychology, Simon Fraser University _______________________________________________ David G. Wagner, PhD External Examiner Professor Department of Sociology, State University of New York Date Defended/Approved: _______________________________________________ -

CRIMINOLOGY: DISCIPLINE OR INTERDISCIPLINE? Arnold Binder

CRIMINOLOGY: DISCIPLINE OR INTERDISCIPLINE? Arnold Binder Program in Social Ecology University of California, Irvine ABSTRACT In its modern form Criminology has had over one hundred years to assume a truly interdisciplinary nature, yet the dominant approach remains discipline-based. However, as the field of Criminology has evolved, the dominant discipline has shifted from medicine and psychology to sociology. The general rejection by sociologists of contributions from other fields seems based not only on normal disciplinary chauvinism, but also on a strongly held normative view that social conditions are more responsible for crime than innate individual differences. Introduction The Disciplinary Contributions A cursory overview of the field of criminology would almost certainly lead to the conclusion that it is solidly interdisciplinary. First, the journal of its leading professional association, the American Society of Criminology, is entitled, Criminology. An Interdisciplinary Journal. Second, the contributors to the field do indeed include people with backgrounds in sociology, psychology, law, political science, economics, medicine, genetics, nutrition, anthropology and history, and they publish hundreds of criminologically oriented articles each year in various "interdisciplinary" journals (others include the Journal of Criminal Justice and Justice Quarterly) as well as in journals of their own disciplines. And third, there is a substantial number of books whose titles demonstrate the diverse array of disciplines that contribute to the field. These books include: Criminal Behavior: A Psychosocial Approach (Bartol 1980), The Economics of Crime (Andreano and Siegfried, 1980), The Sociology of Crime and Delinquency (Wolfgang, Savitz and Johnston, 1970), The Political Science of Criminal Justice (Nagel, Fairchild and Champagne, 1983), Psychology and Criminal Justice (Ellison and Buckhout, 42/ISSUES 1981), Psychiatry and the Dilemmas of Crime (Halleck, 1967), The Frustration of Policy. -

Crime & Delinquency

Crime & Delinquency http://cad.sagepub.com/ Trust in the Police: The Influence of Procedural Justice and Perceived Collective Efficacy Justin Nix, Scott E. Wolfe, Jeff Rojek and Robert J. Kaminski Crime & Delinquency published online 17 April 2014 DOI: 10.1177/0011128714530548 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cad.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/04/16/0011128714530548 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Crime & Delinquency can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cad.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cad.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://cad.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/04/16/0011128714530548.refs.html >> OnlineFirst Version of Record - Apr 17, 2014 What is This? Downloaded from cad.sagepub.com by guest on April 18, 2014 CADXXX10.1177/0011128714530548Crime & DelinquencyNix et al. 530548research-article2014 Article Crime & Delinquency 1 –31 Trust in the Police: The © The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: Influence of Procedural sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0011128714530548 Justice and Perceived cad.sagepub.com Collective Efficacy Justin Nix,1 Scott E. Wolfe,1 Jeff Rojek,1 and Robert J. Kaminski1 Abstract Tyler’s process-based model of policing suggests that the police can enhance their perceived legitimacy and trustworthiness in the eyes of the public when they exercise their authority in a procedurally fair manner. To date, most process-based research has focused on the sources of legitimacy while largely overlooking trust in the police. The present study extends this line of literature by examining the sources of trust in the police. -

Informal Social Control of Crime in High Drug Use Neighborhood: Final Project Report

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Informal Social Control of Crime in High Drug Use Neighborhood: Final Project Report Author(s): Barbara D. Warner Ph.D. ; Carl G. Leukefeld D.S.W ; Pilar Kraman B.A. Document No.: 200609 Date Received: 06/24/2003 Award Number: 99-IJ-CX-0052 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Informal social control of crime in high drug use neighborhoods: Final project report Barbara D. Warner, Ph.D. Carl G. Leukefeld, D.S.W. Pilar Kraman, B.A. Stippofltd unkr Award X 1q?% 3 * cx- 0 0 52 from the National Irstittite of Judcc, Otfice of Justice Programs. U.S Department of Justice. Points ot'view in Illis document are those of thz authors and do not necessarily reprcseiit the otficial position ofthe U.S. Depariment otJustice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.