Fighting Back

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

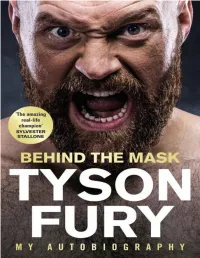

Behind the Mask: My Autobiography

Contents 1. List of Illustrations 2. Prologue 3. Introduction 4. 1 King for a Day 5. 2 Destiny’s Child 6. 3 Paris 7. 4 Vested Interests 8. 5 School of Hard Knocks 9. 6 Rolling with the Punches 10. 7 Finding Klitschko 11. 8 The Dark 12. 9 Into the Light 13. 10 Fat Chance 14. 11 Wild Ambition 15. 12 Drawing Power 16. 13 Family Values 17. 14 A New Dawn 18. 15 Bigger than Boxing 19. Illustrations 20. Useful Mental Health Contacts 21. Professional Boxing Record 22. Index About the Author Tyson Fury is the undefeated lineal heavyweight champion of the world. Born and raised in Manchester, Fury weighed just 1lb at birth after being born three months premature. His father John named him after Mike Tyson. From Irish traveller heritage, the“Gypsy King” is undefeated in 28 professional fights, winning 27 with 19 knockouts, and drawing once. His most famous victory came in 2015, when he stunned longtime champion Wladimir Klitschko to win the WBA, IBF and WBO world heavyweight titles. He was forced to vacate the belts because of issues with drugs, alcohol and mental health, and did not fight again for more than two years. Most thought he was done with boxing forever. Until an amazing comeback fight with Deontay Wilder in December 2018. It was an instant classic, ending in a split decision tie. Outside of the ring, Tyson Fury is a mental health ambassador. He donated his million dollar purse from the Deontay Wilder fight to the homeless. This book is dedicated to the cause of mental health awareness. -

Fury's Comeback Falls Just Short in Los Angeles

PRESENTS FURY’S COMEBACK FALLS JUST SHORT IN LOS ANGELES GOBSMACKED! By William Dettloff yson Fury made but two mistakes Saturday night against Deontay Wilder, and those mistakes – along with an indefensible scorecard turned in by Alejandro TRochin – resulted in a mostly derided draw ver- dict in front of a purported 17,698 at The Sta- ples Center in Los Angeles. Fury – he of the nearly three-year layoff, manic depression, confessed drug and alcohol binges and morbid obesity – boxed Wilder ragged for the majority of the fight, displaying a quickness, dexterity and nimbleness of foot that belied his 6’9”, 256-pound frame. He consistently ducked, rolled with or slipped under Wilder’s attacks, which admittedly were crude at best, and feinted Wilder into knots before stepping forward with short, crisp combinations. “I’m what you call a pro athlete that loves to box,” Fury said afterward. “I don’t know anyone on the planet that can move like that. That man is a fearsome puncher and I was able to avoid that. The world knows I won the fight,” he said. Such was Fury’s early dominance that there was perhaps one round out of the first six that the clear-eyed and uncor- rupted could reasonably give to Wilder. Rochin gifted him the first four, which at the end contributed to an inexplica- ble 115-111 card. Judges Robert Tapper and Phil Edwards scored it a more reasonable 114-112 for Fury and 113-113, respectively. RINGSIDE SEAT saw Fury the winner by a 115-111 margin. -

World Boxing Association Gilberto Mendoza President Official Ratings As of February 2000

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF FEBRUARY 2000 CHAIRMAN GILBERTO MENDOZA FAX: (58-44) 633177 P.O. BOX 377 MARACAY 2101-A VICE CHAIRMAN MEMBERS EDO. ARAGUA - VENEZUELA JORGE H. KLEE FAX: (57-3) 58-0621 PHONE:(44) 63-1584 STANLEY CHRISTODOLOU CBA (SOUTH AFRICA) 63-3347 JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA FEDELATIN (ARGENTINA) FAX: (44) 63-3177 ANIBAL MIRAMONTES NABA (USA) 63-8576 ALAN KIM PABA (KOREA) E-mail: [email protected] SHIGERU KOJIMA JBC (JAPAN) http://www.wbaonline.com/ HEAVYWEIGHT (Over 190 Lbs / Over 86.18 Kgs) CRUISERWEIGHT (190 Lbs / 86.18 Kgs) LIGHT HEAVYWEIGHT (175 Lbs / 79.38 Kgs) World Champion: LENNOX LEWIS G.B World Champion: FABRICE TIOZZO FRA World Champion: ROY JONES USA Won Title: 11-13-99 Won Title: 11-08-97 Won Title: 07-18- 98 Last Mandatory: Last Mandatory: 11-14-98 Last Mandatory: Last Defense: Last Defense: 11-13-99 Last Defense: 01-15-2000 WBC: LENNOX LEWIS - IBF: LENNOX LEWIS WBC: JUAN C. GOMEZ - IBF: VASILI JIROV WBC ROY JONES - IBF: ROY JONES WBO: VITALI KLITSCHKO WBO: JOHNNY NELSON WBO: DARIUSZ MICHALCZEWSKY 1. JOHN RUIZ (WBANA) USA 1. VIRGIL HILL USA 1. RICHARD HALL INTERIM CHAMP USA 2. EVANDER HOLYFIELD USA 2. VALERY VIKHOR (PABA) LAT 2. LOUIS DEL VALLE USA 3. WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO (WBAI-EBU) UKR 3. ALEXANDER GUROV (WBAI) UKR 3. FRANK LILES USA 4. MIKE TYSON USA 4. JAMES TONEY USA 4. DERRICK HARMON (USBA) USA 5. MICHAEL GRANT (NABF) USA 5. IMAMU MAYFIELD USA 5. ERIC HARDIN USA 6. DAVID TUA (USBA) N.Z 6. -

Hennessy Sports Worldwide Ltd, 150 High Street, Sevenoaks, Kent, TN13 1XE England Tel: + 44 (0) 203 146 6000 Office Email: Mick@

150 High Street Sevenoaks Kent TN13 1XE Francisco Valcarcel, President World Boxing Organization 1056 Munoz Rivera Avenue San Juan 00927 Puerto Rico BY EMAIL 6 October 2017 Dear President Valcarcel Notice of Complaint WBO Heavyweight Championship – Joseph Parker v Hughie Fury – 23 September 2017 Please accept this letter as a Complaint submitted to you as President of the WBO pursuant to Article 3 of the WBO Appeal Regulations. The Complainants and interested parties are: Boxer Hughie Lewis Fury Address Hollybank Park, Warburton Bridge Road, Rixton, Warrington WA3 6HC Domicile England Nationality British Telephone Number 07788 874 788 Email Address [email protected] Mailing Address As above Hennessy Sports Worldwide Ltd, 150 High Street, Sevenoaks, Kent, TN13 1XE England Tel: + 44 (0) 203 146 6000 Office Email: [email protected] www.hennessysports.com Promoter Mick Hennessy of Hennessy Sports Worldwide Limited Address 150 High Street, Sevenoaks, Kent TN13 1XE Domicile England Nationality British Telephone Number 0203 146 6050 Email Address [email protected] Mailing Address As above The Complainants and interested parties as referred to above are the challenger and promoter of the WBO World Heavyweight Championship bout that took place at the Manchester Arena on Saturday 23 September 2017. You may consider that Joseph Parker and Duco Promotions Limited are also interested parties. The Complainants consider that the scoring of two of the judges of the bout, John Madfis and Terry O’Connor, do not properly or correctly reflect the contest that took place during the above mentioned bout. Both judges scored the contest in favour of Joseph Parker by 118 to 110 points as compared to the other judge, Rocky Young, who scored the bout as a draw at 114 each (which we still consider to be extremely generous towards Joseph Parker). -

Tyson Fury BBC SPOTY Furore Could Have Been Avoided – They Should Have Chosen Anthony Crolla

BBC SPOTY Tyson Fury Furore could have been avoided Item Type Article Authors Randles, David Citation Randles, D. (2015). BBC SPOTY Tyson Fury Furore could have been avoided. Vice Sports. Retrieved from https:// sports.vice.com/en_uk/article/bbc-spoty-tyson-fury-furore- could-have-been-avoided-they-should-have-chosen-anthony- crolla Publisher Vice Sports Download date 30/09/2021 05:17:40 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/618221 Tyson Fury BBC SPOTY furore could have been avoided – they should have chosen Anthony Crolla By David Randles - @davidrandles It will be interesting to see the table plan for the BBC Sports Personality of the Year awards. While steps will be taken to keep Tyson Fury away from Jessica Ennis-Hill, it may also be wise to put Greg Rutherford at the opposite end of the room to the recently crowned heavyweight champion of the world. It was Fury’s sexist comments about Ennis-Hill, combined with his forthright views aligning homosexuality and pedophilia, that riled Rutherford enough for the Olympic long jump champion to withdraw from the SPOTY 2015 running before changing his mind. Joining the chorus of condemnation for Fury are Northern Ireland’s largest gay rights group the Rainbow Project, who this week labeled his comments as ‘extremely callous’ and ‘erroneous’. In response to Fury’s insistence that a woman’s place is ‘in the kitchen or on her back’, feminist group Fight4Equality has blasted the self-titled Gypsy King’s ‘neanderthal worldview’ insisting Fury ‘should not be feted as a role model for young people.’ Both groups will be joined by other LGBT campaigners outside Belfast’s SSE Arena on Sunday evening to picket the BBC, angry that the show will go on despite vocal public opposition to Fury’s involvement. -

Tyson Fury Back at a Work on One Plan That Emerged After He Was

Media Workout: Tyson Fury & Otto Wallin Kick off Mexican Independence Day Weekend Card in Style LAS VEGAS (Sept. 10, 2019) —Tyson Fury sure knows how to dress for the occasion. Fury, the lineal heavyweight champion, entered Tuesday’s media workout in a traditional lucha libre wrestling mask. Fury will defend his title against fellow unbeaten Otto Wallin Saturday at T-Mobile Arena as part of the Las Vegas’ Mexican Independence Day Weekend festivities. WBO junior featherweight world champion Emanuel Navarrete will defend his title against Juan Miguel Elorde in the co-feature (ESPN+, 11 p.m. ET), while former two-division world champion Jose Pedraza will take on Mexican veteran Jose Zepeda in a 10-round super lightweight showdown. The entire undercard, including Pedraza-Zepeda and appearances by Gabriel Flores Jr. and heavyweight sensation Guido Vianello, will stream live on ESPN+ starting at 7:30 p.m. ET/4:30 p.m. PT. This is what the fighters had to say at the media workout. Tyson Fury “I’m just enjoying life, taking one day at a time and inspiring people to do well in their life, too.” “I wore a traditional Mexican mask because it’s Mexican Independence Day Weekend and the ‘Gypsy King’ is here in Las Vegas to put on a show for all the Mexican fans. Viva Mexico!” “I can defeat all the heavyweights with one hand. As you saw today, lightning speed, lightning reflexes for a giant. I’m a giant of a heavyweight. There has never been a heavyweight like me. There has never been a man of my size who can move like that. -

Mccall – OQUENDO IBF INTER CONTINENTAL HEAVYWEIGHT TITLE CLASH TOMORROW NIGHT LIVE on GFL

McCALL – OQUENDO IBF INTER CONTINENTAL HEAVYWEIGHT TITLE CLASH TOMORROW NIGHT LIVE ON GFL CLICK TO ORDER THE FIGHT HOLLYWOOD, FLA/ NEW YORK (December 6, 2010)—TOMORROW night, a crossroads heavyweight fight between former Heavyweight champion Oliver McCall and former world title challenger Fres Oquendo will take place with huge implications for the winner. The bout will headline a card from the beautiful Seminole Hard Rock Hotel and Casino in Hollywood, Florida and will be seen around the world, LIVE on www.gofightlive.tv The bout will be for the IBF Intercontinental Heavyweight championship. The bout plus a full undercard can be seen LIVE at 7pm est. for just $9.99 by clicking: http://www.gofightlive.tv/Events/Fight/Boxing/Tuesday_Night_Fi ghts__McCall_Vs_Oquendo/894 With the consistent uncertainty in the Heavyweight division, the winner of this bout will get a big leg up in being able to once again compete for the Heavyweight championship of the world. McCall has a career that has spanned twenty-five years, has a record of 54-10 with thirty-seven knockouts. McCall has been in the ring with just about every big-time Heavyweight that has competed in the last quarter century as he has shared the ring with former undisputed champion James “Buster” Douglas (L 10); Former Cruiserweight champion Orlin Norris (L 10) ; Former WBA Heavyweight champion Bruce Seldon (TKO 9); former world title challenger Tony Tucker ( L 12) before shocking the world by stopping WBC Heavyweight champion Lennox Lewis with the right hand heard round the world on September 24, 1994. McCall made one defense against the legendary Larry Holmes before dropping the belt to Frank Bruno in Bruno’s homeland of England. -

Ancient Games: Tyson Fury Jabs at Wilder with Rhetorical Feints

Ancient Games: Tyson Fury jabs at Wilder with rhetorical feints By Norm Frauenheim- Tyson Fury calls himself a boxing historian, which means more than a basic understanding of what it is to be the lineal heavyweight champion. Mostly, it means he understands deception. He practices the art and even drops occasional references to Sun Tzu, an ancient philosopher quoted by Generals, cornermen, West Point professors and lineal heavyweight champs. Deontay Wilder calls Fury a con man and maybe he is. But a fighter without a good con enters the ring without a fundamental weapon. No feint, no chance. “All warfare is based on deception,’’ Tzu said in his classic, The Art of War. “Appear weak when you are strong, and strong when you are weak,’’ he also wrote. Those are quotes to remember as Fury’s rematch with Wilder approaches on Feb. 22 at Las Vegas’ MGM Grand in a Fox/ESPN pay-per-view bout. Between sticking out his tongue and mocking Wilder with dancing eyes, Fury talks. And talks. It’s hard to know what’s real and what’s fake, what’s true and what’s feint. But that’s the idea in the buildup, a series of news conferences that set the stage for the head games that precede any opening bell. Fury is trying to confuse Wilder, who knocked him down twice with the most feared right hand in at least a generation. Wilder says there’s no eluding his power. Few have. His record includes an astonishing 41 stoppages in 43 fights. But the record also includes the draw with Fury Dec. -

The Ethics of Knowing the Score: Recommendations for Improving Boxing’S 10-Point Must System

Journal of Ethical Urban Living The Ethics of Knowing the Score: Recommendations for Improving Boxing’s 10-Point Must System John Scott Gray Ferris State University Brian R. Russ Indiana University - Purdue University of Columbus Biographies John Scott Gray is a Professor of Philosophy and Distinguished Teacher at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, MI. His research interests focus on areas of applied philosophy, including the Philosophy of Sports, Sex and Love, and Popular Culture. Dr. Gray co-authored Introduction to Popular Culture: Theories, Applications, and Global Perspectives (2013). He lives in Canadian Lakes, MI with his wife Jo and son Oscar. Brian R. Russ is an Assistant Professor of Mental Health Counseling at Indiana University – Purdue University of Columbus in Columbus, IN. His research interests include sports counseling and adolescent mental health. Dr. Russ lives in Columbus with his wife and three children, and he is a lifelong boxing fan. Publication Details Journal of Ethical Urban Living (ISSN: 2470-2641). March, 2019. Volume 2, Issue 1. Citation Gray, John Scott, and Brian R. Russ. 2019. “The Ethics of Knowing the Score: Recommendations for Improving Boxing’s 10-Point Must System.” Journal of Ethical Urban Living 2 (1): 51–62. The Ethics of Knowing the Score: Recommendations for Improving Boxing’s 10-Point Must System John Scott Gray and Brian R. Russ Abstract The sport of boxing has been a mainstay in urban settings since the late 19th century. Although there have been changes in the sport to enhance safety and justice, the 10-Point Must scoring system continues to be problematic. -

152370921.Pdf

Introduction This book is intended to give the reader an inside look at what it is like to train at Greyskull. The program presented follows a hypothetical male trainee through twelve grueling weeks designed to elicit a greater level of strength, conditioning, and all-around toughness. This is by no means a default representation of the training conducted here, but rather a snapshot of some of the methods that we employ.y. Undertaking this program for twelve weeks will certainly produce for you a very favorable set of results. I’m frequently asked what to do once one is done with the Greyskull LP (the basic program presented in my book “The Greyskull LP: Second Edition). While the GSLP is almost infinitely flexible and adaptable, programs like the one presented in this book are still commonplace for trainees who have been at it a bit longer. This program takes a holistic approach to strength and conditioning. My “layering” method is used full bore here, combining strength training with weights, high intensity conditioning, track sprinting, running, and “homework”; smaller sessions designed to be completed daily at the end of the day. The elements compliment each other, and strike a perfect balance in terms of maximizing the amount of work that can be asked of you over the course of a week, and not overtraining you. The demands here are high. The result is aa strong, capable, aesthetically pleasing body that will help you equally attract smoking hot females, and demolish their boyfriends that are unhappy with you for stealing their girl. -

Heavyweight Cruiserweight

WBA RATINGS COMMITTEE JUNE 2014 MOVEMENTS REPORT nd th Based on results held from 02 June to July 06 , 2014 Miguel Prado Sanchez Chairman Gustavo Padilla Vice Chairman HEAVYWEIGHT DATE PLACE BOXER A RESULT BOXER B TITLE REMARKS S. Atwood 120-106 E. Standridge 120-106 06-28-2014 Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Shannon Briggs UD12 Raphael Zumbano Vacant NABA C. Ritter 118-109 07-06-2014 Grozny ,Russia Ruslan Chagaev MD12 Fres Oquendo Vacant WBA WORLD MOVEMENT N° 3 Ruslan Chagaev removed from the rating after winning the vacant WBA title vs Fres Oquendo by majority decision OUT N° 15 Jovo Pudar removed from the rating due to inactivity (265 days) Lateef Kayode enters at N° 5 due to his record (20-0-0,16 KO’s) and caliber IN Shannon Briggs enters at N° 14 after winning regional championships (WBA- NABA) N° 5 Alexander Povetkin goes up to position N° 3, N° 7 Bryant Jennings goes up to position N° 4 due to Chagaev’s promotion to WBA champion and Oquendo’s demotion PROMOTIONS N° 8 Deontay Wilder goes up to position N° 6 due to Chagaev’s promotion to WBA champion and Kaufman’s demotion N° 12 Dereck Chisora goes up to position N° 8 at the discretion of the ratings committee N° 14 Tyson Fury goes up to position N° 12 at the discretion of the ratings committee N° 4 Fres Oquendo goes down to position N° 7 after losing the vacant WBA regular tittle vs Ruslan Chagaev by UD DEMOTIONS N° 7 Bryant Kauffman goes down to position N° 15 after refusing to fight for the WBA Title. -

General Household Sale Tuesday 08 February 2011 10:00

General Household Sale Tuesday 08 February 2011 10:00 Frank Marshall & Co Marshall House Church Hill Knutsford WA16 6DH Frank Marshall & Co (General Household Sale) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 Lot: 12 A single piece John Bennett & Co snooker cue with case H Shore; oil on canvas entitled 'High Torr Matlock' and a further Estimate: £10.00 - £20.00 oil highland cattle at water indistinctly signed, (2) Estimate: £30.00 - £50.00 Lot: 2 A Lee & Pershore of Redditch Black Demon three section split Lot: 13 cane fishing rod with canvas bag A 20th century Dutch oil on panel depicting canal street scene, Estimate: £15.00 - £30.00 possible indistinct signature in carved ebonised frame and two prints, (3) Estimate: £40.00 - £60.00 Lot: 3 A 20th century ornamental wall piece sabre Estimate: £15.00 - £20.00 Lot: 14 A 19th century mahogany and boxwood strung wheel barometer by A Colomba of 57 Charles Street, Hatton Gardens, Lot: 4 the arched pediment with brass finial above silvered A pair of late 19th/early 20th century fencing foils, the square temperature scale and dial, with adjuster knob, length 100cm tapering blades stamped Solingen, length of blades 87cm's, Estimate: £150.00 - £250.00 with pierced steel guard with leather backing, string bound grip terminating in a turned brass pummel (2) Estimate: £40.00 - £60.00 Lot: 15 A mixed lot of assorted sundries to include chromed Art Deco lamp, map measure camera, boxed octopus microscope etc Lot: 5 Estimate: £20.00 - £30.00 A 19th century brass bound oak log barrel with swing