Shakespeare's French: Reading Hamlet at the Edge of English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View in Order to Answer Fortinbras’S Questions

SHAKESPEAREAN VARIATIONS: A CASE STUDY OF HAMLET, PRINCE OF DENMARK Steven Barrie A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2009 Committee: Dr. Stephannie S. Gearhart, Advisor Dr. Kimberly Coates ii ABSTRACT Dr. Stephannie S. Gearhart, Advisor In this thesis, I examine six adaptations of the narrative known primarily through William Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark to answer how so many versions of the same story can successfully exist at the same time. I use a homology proposed by Gary Bortolotti and Linda Hutcheon that explains there is a similar process behind cultural and biological adaptation. Drawing from the connection between literary adaptations and evolution developed by Bortolotti and Hutcheon, I argue there is also a connection between variation among literary adaptations of the same story and variation among species of the same organism. I determine that multiple adaptations of the same story can productively coexist during the same cultural moment if they vary enough to lessen the competition between them for an audience. iii For Pam. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Stephannie Gearhart, for being a patient listener when I came to her with hints of ideas for my thesis and, especially, for staying with me when I didn’t use half of them. Her guidance and advice have been absolutely essential to this project. I would also like to thank Kim Coates for her helpful feedback. She has made me much more aware of the clarity of my sentences than I ever thought possible. -

The New Cambridge Shakespeare

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82544-3 - The Merchant of Venice Edited by M. M. Mahood Frontmatter More information THE NEW CAMBRIDGE SHAKESPEARE GENERAL EDITOR Brian Gibbons ASSOCIATE GENERAL EDITOR A. R. Braunmuller, University of California, Los Angeles From the publication of the first volumes in 1984 the General Editor of the New Cambridge Shakespeare was Philip Brockbank and the Associate General Editors were Brian Gibbons and Robin Hood. From 1990 to 1994 the General Editor was Brian Gibbons and the Associate General Editors were A. R. Braunmuller and Robin Hood. THE MERCHAnt OF VENICE The Merchant of Venice has been performed more often than any other comedy by Shakespeare. Molly Mahood pays special attention to the expectations of the play’s first audience, and to our modern experience of seeing and hearing the play. In a substantial new addition to the Introduction, Charles Edelman focuses on the play’s sex- ual politics and recent scholarship devoted to the position of Jews in Shakespeare’s time. He surveys the international scope and diversity of theatrical interpretations of The Merchant in the 1980s and 1990s and their different ways of tackling the troubling figure of Shylock. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82544-3 - The Merchant of Venice Edited by M. M. Mahood Frontmatter More information THE NEW CAMBRIDGE SHAKESPEARE All’s Well That Ends Well, edited by Russell Fraser Antony and Cleopatra, edited by David Bevington As You Like It, edited by Michael Hattaway The Comedy of Errors, edited by T. -

The Tragedy of Hamlet

THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET EDITED BY EDWARD DOWDEN n METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON 1899 9 5 7 7 95 —— CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ix The Tragedy of Hamlet i Appendix I. The "Travelling" of the Players. 229 Appendix II.— Some Passages from the Quarto of 1603 231 Appendix III. Addenda 235 INTRODUCTION This edition of Hamlet aims in the first place at giving a trustworthy text. Secondly, it attempts to exhibit the variations from that text which are found in the primary sources—the Quarto of 1604 and the Folio of 1623 — in so far as those variations are of importance towards the ascertainment of the text. Every variation is not recorded, but I have chosen to err on the side of excess rather than on that of defect. Readings from the Quarto of 1603 are occa- sionally given, and also from the later Quartos and Folios, but to record such readings is not a part of the design of this edition. 1 The letter Q means Quarto 604 ; F means Folio 1623. The dates of the later Quartos are as follows: —Q 3, 1605 161 1 undated 6, For ; Q 4, ; Q 5, ; Q 1637. my few references to these later Quartos I have trusted the Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness's edition of Hamlet. Thirdly, it gives explanatory notes. Here it is inevitable that my task should in the main be that of selection and condensation. But, gleaning after the gleaners, I have perhaps brought together a slender sheaf. -

Template EUROVISION 2021

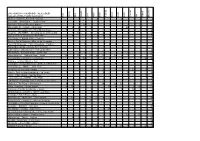

Write the names of the players in the boxes 1 to 4 (if there are more, print several times) - Cross out the countries that have not reached the final - Vote with values from 1 to 12, or any others that you agree - Make the sum of votes in the "TOTAL" column - The player who has given the highest score to the winning country will win, and in case of a tie, to the following - Check if summing your votes you’ve given the highest score to the winning country. GOOD LUCK! 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Anxhela Peristeri “Karma” Albania Montaigne “ Technicolour” Australia Vincent Bueno “Amen” Austria Efendi “Mata Hari” Azerbaijan Hooverphonic “ The Wrong Place” Belgium Victoria “Growing Up is Getting Old” Bulgaria Albina “Tick Tock” Croatia Elena Tsagkrinou “El diablo” Cyprus Benny Christo “ Omaga “ Czech Fyr & Flamme “Øve os på hinanden” Denmark Uku Suviste “The lucky one” Estonia Blind Channel “Dark Side” Finland Barbara Pravi “Voilà” France Tornike Kipiani “You” Georgia Jendrick “I Don’t Feel Hate” Germany Stefania “Last Dance” Greece Daði og Gagnamagnið “10 Years” Island Leslie Roy “ Maps ” Irland Eden Alene “Set Me Free” Israel 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Maneskin “Zitti e buoni” Italy Samantha Tina “The Moon Is Rising” Latvia The Roop “Discoteque” Lithuania Destiny “Je me casse” Malta Natalia Gordienko “ Sugar ” Moldova Vasil “Here I Stand” Macedonia Tix “Fallen Angel” Norwey RAFAL “The Ride” Poland The Black Mamba “Love is on my side” Portugal Roxen “ Amnesia “ Romania Manizha “Russian Woman” Russia Senhit “ Adrenalina “ San Marino Hurricane “LOCO LOCO” Serbia Ana Soklic “Amen” Slovenia Blas Cantó “Voy a quedarme” Spain Tusse “ Voices “ Sweden Gjon’s Tears “Tout L’Univers” Switzerland Jeangu Macrooy “ Birth of a new age” The Netherlands Go_A ‘Shum’ Ukraine James Newman “ Embers “ United Kingdom. -

EDITING for PERFORMANCE: DR JOHNSON and the STAGE I Want

Editing for performance... 75 EDITING FOR PERFORMANCE: DR JOHNSON AND THE STAGE Peter Holland Notre Dame University I want to begin by quoting one of Dr Johnson’s notes on Hamlet, a passage that, though entirely characteristic, may be less than familiar to many. Johnson is commenting on the punctuation of a passage and is concerned about a sequence of dashes towards the end of the play: To a literary friend of mine I am indebted for the following very acute observation: “Throughout this play,” says he, “there is nothing more beautiful than these dashes; by their gradual elongation, they distinctly mark the balbuciation and the increasing difficulty of utterance observable in a dying man.” To which let me add, that, although dashes are in frequent use with our tragic poets, yet they are seldom introduced with so good an effect as in the present instance. (qtd. in Wells 1: 69) Johnson’s reliance on others—and their cloaked identity—is something we are used to. So too Johnson’s yearning here both to generalize about tragic practice and to praise the particular local effect in Shakespeare can be paralleled frequently elsewhere. There is that precision that is Ilha do Desterro Florianópolis nº 49 p.075-098 jul./dez. 2005 76 Peter Holland also apparent in Johnson’s note on Ophelia’s reference to “a rope of onions”, a phrase that Pope had suggested emending to “a robe of onions”: Rope is, undoubtedly, the true reading. A rope of onions is a certain number of onions, which, for the convenience of portability, are, by the market-women, suspended from a rope: not, as the Oxford editor ingeniously, but improperly, supposes, in a bunch at the end, but by a perpendicular arrangement. -

Garrick's Alterations of Shakespeare

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88977-3 - Shakespeare and Garrick Vanessa Cunningham Excerpt More information prologue Garrick’s alterations of Shakespeare – a note on texts The great majority of the versions of Shakespeare’s plays made by David Garrick and published during his management of Drury Lane (1747– 1776) are described on their title pages as ‘alterations’, or as having been 1 ‘alter’d for performance’. The two operas (The Fairies, 1755, and The Tempest, 1756) are said to be ‘taken from Shakespear’, while Antony and Cleopatra,publishedin1758 and generally credited jointly to Edward Capell and Garrick (though not attributed to either on the title page), is dis- tinguished from the others by its description as ‘an historical Play, written by William Shakespeare: fitted for the Stage by abridging only’. Despite the fact that Harry William Pedicord and Fredrick Louis Bergmann, modern editors of Garrick’s plays, entitle their two volumes of Shakespeare- 2 derived texts ‘adaptations’, ‘alteration’ is certainly the preferable term for discussion of Garrick’s performance versions of Shakespeare’s plays, since throughout the eighteenth century ‘alter’ was used far more commonly than ‘adapt’. Garrick, according to Pedicord and Bergmann, is believed to have been involved in the altering of some twenty-two plays by Shakespeare over the course of his professional career. In their collected edition they reproduce 3 the dozen that they consider can be authenticated. The present work discusses a selection of alterations that span Garrick’s professional career. Two are from the early years (Macbeth, Romeo and Juliet) and two from the middle period (Florizel and Perdita, Antony and Cleopatra). -

![Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -In Memoriam]Ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7141/montaignes-unknown-god-and-melvilles-confidence-man-in-memoriam-ohn-spencer-hill-1943-1998-977141.webp)

Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -In Memoriam]Ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998)

CAMILLE R. LA Bossr:ERE The World Revolves Upon an I: Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -in memoriam]ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998) Les mestis qui ont ... le cul entre deux selles, desquels je suis ... I The mongrel! sorte, of which I am one ... sit betweene two stooles -Michel de Montaigne, "Des vaines subtilitez" I "Of Vaine Subtilties" Deus est anima brutorum. -Oliver Goldsmith, "The Logicians Refuted" YEA AND NAY EACH HATH HIS SAY: BUT GOD HE KEEPS THF MTDDT.F WAY -Herman Melville, "The Conflict of Convictions" T ATE-MODERN SCHOLARLY accounts of Montaigne and his L oeuvre attest to the still elusive, beguilingly ironic character of his humanism. On the one hand, the author of the Essais has in vited recognition as "a critic of humanism, as part of a 'Counter Renaissance'."' The wry upending of such vanity as Protagoras served to model for Montaigne-"Truely Protagoras told us prettie tales, when he makes man the measure of all things, who never knew so much as his owne," according to the famous sentence 1 Peter Burke, Montaigne (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1981) 11. 340 • THE DALHOUSIE REvlEW from the "Apologie of Raimond Sebond"2-naturally comes to mind when he is thought of in this way (Burke 12). On the other hand, Montaigne has been no less justifiably recognized by a long line of twentieth-century commentators3 as a major contributor to the progress of an enduring philosophy "qui fait de l'homme, selon la tradition antique, la valeur premiere et vise a son plein epa nouissement. -

Writing the Shakespeare Mask: the Novelist's Choices

Writing The Shakespeare Mask: The Novelist’s Choices Newton Frohlich *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Copyright©2016 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract The authorship of the works of Shakespeare by de Vere is depicted from when he was five to the time of his the glover from Stratford -on-Avon has been considered a tragic death, including his "favored," sexual relationship myth almost from its inception. No less than Charles Dickins, with the queen and his intimate relationship with Emilia Mark Twain, Henry and William James, Ralph Waldo Bassano, who is widely accepted as the "Dark Lady" of Emerson, Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, Royal Shake-speare's Sonnets. (There is no evidence of any Shakespeare Company actors John Gielgud, Derek Jacobi, relationship between the Stratford man and Emilia Bassano.) Jeremy Irons, and Michael York, British Prime Minister In short, while the documentary evidence of de Vere's -- or Benjamin Disraeli, five United States Supreme Court the Stratford man's -- authorship of the works of Shakespeare Justices, and thousands who signed a Declaration of Doubt is missing, the circumstantial evidence of de Vere's About Will circulating the World-Wide Web have attested to authorship is overwhelming. And as United States Supreme their doubts. In response to the request by his publisher, Court Justice John Paul Stevens puts it, "circumstantial author Newton Frohlich, commencing research connected evidence can be as persuasive as documentary evidence with a sequel to his novel about Columbus, came across especially where, as here, there's so much of it. -

University of California Santa Cruz Romance

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ ROMANCE: THE EMULATION OF EMPIRE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LITERATURE by Martha E. Bonilla December 2016 The Dissertation of Martha E. Bonilla is approved: __________________________________ Professor Susan Gillman, chair __________________________________ Professor Kirsten Silva Gruesz __________________________________ Professor Catherine A. John _____________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Martha E. Bonilla 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents………………………………………………………………..iii Abstract………………………………………………………..…………..……..iv Acknowledgement………………………………………………………………..vi Chapter 1 Romance as the Desire for Empire: An Introduction…………………….………..1 Chapter 2 The Tempest, a Romance for a New World of Empire…………………….…..…58 Chapter 3 Remembering to Forget: Desire, Emulation, and Romance in J.F. Cooper’s The Pioneers……………………..…………………….………….113 Chapter 4 Benito Cereno’s Black Letter Text: The Unread Story of Empire……..…..……159 . Chapter 5 The Happy Resolution and the Solace of Amnesia……………..……………..….204 Epilogue The Don of a Pervious Age…….……..………………………………..…………227 Bibliography………………………………………………………….………..….251 iii ABSTRACT Martha E. Bonilla Romance: The Emulation of Empire This dissertation offers a symptomatic reading of romance and explores the ideological force of the genre’s chiastic structure. The trajectory of this project follows the temporal and spatial migration of romance from the colonial context of early seventeenth England, beginning with William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, then enters the American post-revolutionary context of the early and late nineteenth century with James Fennimore Cooper’s The Pioneers, Herman Melville’s “Benito Cereno,” and ends with Maria Amparo Ruiz de Burton’s The Squatter and the Don. This study examines the contradictory narrative desires within romance. -

Amleth, Prince of Denmark

Amleth, Prince of Denmark Saxo Grammaticus Amleth, Prince of Denmark Table of Contents Amleth, Prince of Denmark From the Gesta Danorum of Saxo Grammaticus..................................................1 translated by Oliver Elton..............................................................................................................................1 i Amleth, Prince of Denmark From the Gesta Danorum of Saxo Grammaticus translated by Oliver Elton Horwendil, King of Denmark, married Gurutha, the daughter of Rorik, and she bore him a son, whom they named Amleth. Horwendil's good fortune stung his brother Feng with jealousy, so that the latter resolved treacherously to waylay his brother, thus showing that goodness is not safe even from those of a man's own house. And behold when a chance came to murder him, his bloody hand sated the deadly passion of his soul. Then he took the wife of the brother he had butchered, capping unnatural murder with incest. For whoso yields to one iniquity, speedily falls an easier victim to the next, the first being an incentive to the second. Also the man veiled the monstrosity of his deed with such hardihood of cunning, that he made up a mock pretense of goodwill to excuse his crime, and glossed over fratricide with a show of righteousness. Gerutha, said he, though so gentle that she would do no man the slightest hurt, had been visited with her husband's extremest hate; and it was all to save her that he had slain his brother; for he thought it shameful that a lady so meek and unrancorous should suffer the heavy disdain of he husband. Nor did his smooth words fail in their intent; for at courts, where fools are sometimes favored and backbiters preferred, a lie lacks not credit. -

Shakespeare Apocrypha” Peter Kirwan

The First Collected “Shakespeare Apocrypha” Peter Kirwan he disparate group of early modern plays still referred to by many Tcritics as the “Shakespeare Apocrypha” take their dubious attributions to Shakespeare from a variety of sources. Many of these attributions are external, such as the explicit references on the title pages of The London Prodigal (1605), A Yorkshire Tragedy (1608), 1 Sir John Oldcastle (1619), The Troublesome Raigne of King John (1622), The Birth of Merlin (1662), and (more ambiguously) the initials on the title pages of Locrine (1595), Thomas Lord Cromwell (1602), and The Puritan (1607). Others, including Edward III, Arden of Faversham, Sir Thomas More, and many more, have been attributed much later on the basis of internal evidence. The first collection of disputed plays under Shakespeare’s name is usually understood to be the second impression of the Third Folio in 1664, which “added seven Playes, never before Printed in Folio.”1 Yet there is some evidence of an interest in dubitanda before the Restoration. The case of the Pavier quar- tos, which included Oldcastle and Yorkshire Tragedy among authentic plays and variant quartos in 1619, has been amply discussed elsewhere as an early attempt to create a canon of texts that readers would have understood as “Shakespeare’s,” despite later critical division of these plays into categories of “authentic” and “spu- rious,” which was then supplanted by the canon presented in the 1623 Folio.2 I would like to attend, however, to a much more rarely examined early collection of plays—Mucedorus, Fair Em, and The Merry Devil of Edmonton, all included in C. -

P E Ti Is Tv Á N O Rs I L Á S Z Ló L E V I a Ttila B E Tti P . R O B I

n e i s l b ó l e m n l i i o i i z u a f o z i i á i t s l b s t i t R ESC HUNGARY RAJONGÓI TALÁLKOZÓ c b s v ó s i v z t t t r s o e t e . r i s a á e s m 2021-08-28 HELYSZÍNI SZAVAZÁS P I O L L A B P E Z R T I P Ö Albánia – Anxhela Peristeri – Karma 3 2 1 3 9 Ausztrália – Montaigne – Technicolour 5 5 Ausztria – Vincent Bueno – Amen 10 2 2 14 Azerbajdzsán – Efendi – Mata Hari 1 1 5 8 7 10 6 38 Belgium – Hooverphonic – The Wrong Place 6 4 3 6 19 Bulgária – VICTORIA – Growing Up Is Getting Old 7 10 7 7 6 4 41 Ciprus – Elena Tsagrinou – El Diablo 3 4 3 3 4 3 2 22 Csehország – Benny Cristo – omaga 0 Dánia – Fyr & Flamme – Øve os på hinanden 1 1 Egyesült Királyság – James Newman – Embers 5 6 1 12 Észak-Macedónia – Vasil – Here I Stand 0 Észtország – Uku Suviste – The Lucky One 7 4 11 Finnország – Blind Channel – Dark Side 2 2 8 12 Franciaország – Barbara Pravi – Voilà 10 12 12 12 12 12 4 3 2 79 Görögország – Stefania – Last Dance 12 4 5 2 6 10 39 Grúzia – Tornike Kipiani – You 0 Hollandia – Jeangu Macrooy – Birth of a New Age 8 7 4 19 Horvátország – Albina – Tick-Tock 7 2 8 17 Írország – Lesley Roy – Maps 2 5 12 8 27 Izland – Daði og Gagnamagnið – 10 Years 7 6 3 5 1 22 Izrael – Eden Alene – Set Me Free 1 3 2 6 Lengyelország – RAFAŁ – The Ride 8 7 15 Lettország – Samanta Tīna – The Moon Is Rising 1 1 Litvánia – The Roop – Discoteque 4 5 8 10 10 10 4 51 Málta – Destiny – Je me casse 8 10 12 4 6 10 50 Moldova – Natalia Gordienko – Sugar 5 10 8 23 Németország – Jendrik – I Don’t Feel Hate 0 Norvégia – TIX – Fallen Angel 0 Olaszország – Måneskin