A Professional Journal of National Defence College Volume 7 Number

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIRPUR PAPERS, Volume 22, Issue 23, November 2016

ISSN: 1023-6325 MIRPUR PAPERS, Volume 22, Issue 23, November 2016 MIRPUR PAPERS Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka-1216 Bangladesh MIRPUR PAPERS Chief Patron Major General Md Saiful Abedin, BSP, ndc, psc Editorial Board Editor : Group Captain Md Asadul Karim, psc, GD(P) Associate Editors : Wing Commander M Neyamul Kabir, psc, GD(N) (Now Group Captain) : Commander Mahmudul Haque Majumder, (L), psc, BN : Lieutenant Colonel Sohel Hasan, SGP, psc Assistant Editor : Major Gazi Shamsher Ali, AEC Correspondence: The Editor Mirpur Papers Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka – 1216, Bangladesh Telephone: 88-02-8031111 Fax: 88-02-9011450 E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2006 DSCSC ISSN 1023 – 6325 Published by: Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka – 1216, Bangladesh Printed by: Army Printing Press 168 Zia Colony Dhaka Cantonment, Dhaka-1206, Bangladesh i Message from the Chief Patron I feel extremely honoured to see the publication of ‘Mirpur Papers’ of Issue Number 23, Volume-I of Defence Services Command & Staff College, Mirpur. ‘Mirpur Papers’ bears the testimony of the intellectual outfit of the student officers of Armed Forces of different countries around the globe who all undergo the staff course in this prestigious institution. Besides the student officers, faculty members also share their knowledge and experience on national and international military activities through their writings in ‘Mirpur Papers’. DSCSC, Mirpur is the premium military institution which is designed to develop the professional knowledge and understanding of selected officers of the Armed Forces in order to prepare them for the assumption of increasing responsibility both on staff and command appointment. -

Bangladesh Gazette

Registered No. DA-1 Bangladesh Gazette Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Additional issue Published by the Authority Monday, September 24, 2012 Bangladesh National Parliament Dhaka, 24 September, 2012/09 Ashwin, 1419 Following Act is adopted by the Parliament and got consent of the President on 24 September, 2012/09 Ashwin, 1419 and the Act is hereby going to be published for information of the public:- Act No. 34 of the year 2012 The Act enacted to make the activities about disaster management coordinated, object oriented and strengthened and to formulate rules to build up infrastructure of effective disaster management to fight all types of disaster Whereas, it is expedient and necessary to mitigate overall disaster, conduct post disaster rescue and rehabilitation program with more skill, provide emergency humanitarian aid to vulnerable community by bringing the harmful effect of disaster to a tolerable level through adopting disaster risk reduction programs and to enact rules to create effective disaster management infrastructure to fight disaster to make the activities of concerned public and private organizations more coordinated, object oriented and strengthened to face the disasters; Therefore, the following Act is enacted hereby: -- ------------------------------------------------------------ (173441) Value : Tk. 30.00 173442 Bangladesh Gazette, additional issue, September 24, 2012 Chapter one Preamble 1. Short Title and Commencement.-- (1) This Act may be called as Disaster Management Act. (2) It would come in -

Company Profile

Nogor Solutions Limited Enabling ICT Solutions for you Company Profile Nogor Solutions Limited House No. 69 (4th floor), Road No. 08, Block-D, Niketon, Gulshan-1, Dhaka-1212. Web: www.nogorsolutions.com Nogor Solutions Limited Enabling ICT Solutions for you Profile of NOGOR Solutions Limited INTRODUCTION The revolution of the IT industry has a great influence on the development of modern civilization. Believing this development as an art the NOGOR Solutions Limited, one of the leading IT firms in Bangladesh is creating some success stories to contribute in the global IT industry. In this era of globalization, IT solutions like software solutions, web development and networking are some basic needs for organizational development and businesses are getting dependent on these everywhere. For this reason, organizations that do not have IT infrastructure are facing problem to compete with those who have a strong lead in the IT world. Considering all these facts, NOGOR Solutions Limited started its business in 2009 to provide the highest level of professional service to the organizations and individuals to create a strong IT infrastructure. Now it has become a recognized IT solution provider which has been providing anything on desktop, web, in networking & in developing any software without any complication to clients worldwide. Being in IT business for over 7 years now, it has a skilled expert team with good experience in Web and Software development. NOGOR Solutions Limited are providing various ICT Services for last 7 years in Bangladesh and also earn foreign remittance by offshore software Development for the various countries like, UK, USA, Canada and Australia. -

“Knowledge Is Power”

“KNOWLEDGE IS POWER” PROSPECTUS DSCSC 2021-2022 DEFENCE SERVICES COMMAND AND STAFF COLLEGE MIRPUR, DHAKA, BANGLADESH CONTENTS Page Contents i Foreword by Commandant ii Part I: Overview of DSCSC Introduction, Vision and Course Mission 1 Course Contents 2 Course Duration, Working Hours and MSc Programme 3 Graduation, Faculty and Staff 4 Organogram of DSCSC 5 Overseas Course Participants‟ Participation 6 Course Activities 7 College Facilities 11 Outline Programme of DSCSC Course 2021-2022 13 Part II: Administration Location 14 Arrival, Accommodation and Dress 15 Electronic, Baggage, Stationery, Transport, Leave Medical, Pay and Allowance 16 Financial Aspects, Service Charges, Utilities and Maintenance Charge, Personal Expenditures, Registration Fee for the 17 Masters Programme at Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP) and Banking Addresses, Discipline, Detailed Administrative Instructions, Course Participant In-Processing Data and Medical Fitness Certificate 18 Course Participant In-Processing Data Form 19 Medical Fitness Certificate Form 25 Part III: Basic Information on Bangladesh General Information 27 Airlines Operating – Bangladesh and Airline Representatives 28 Map of Bangladesh 29 i FOREWORD BY COMMANDANT I am very delighted to welcome the Course Participants and their families at Defence Services Command and Staff College (DSCSC) Mirpur, your home for an exciting journey ahead. This is a life time opportunity for the Course Participants to pursue academic excellence from different cultures of the world. The College offers a conducive environment to enhance the professional knowledge and skills imbued with military norms and ethos. I believe that you shall be able to build a lifelong bond of friendship with people coming from all over the globe. Life in DSCSC is a small chronicle that will be treasured by all alumni forever. -

Download File

Cover and section photo credits Cover Photo: “Untitled” by Nurus Salam is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 (Shangu River, Bangladesh). https://www.flickr.com/photos/nurus_salam_aupi/5636388590 Country Overview Section Photo: “village boy rowing a boat” by Nasir Khan is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nasir-khan/7905217802 Disaster Overview Section Photo: Bangladesh firefighters train on collaborative search and rescue operations with the Bangladesh Armed Forces Division at the 2013 Pacific Resilience Disaster Response Exercise & Exchange (DREE) in Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonmildep/11856561605 Organizational Structure for Disaster Management Section Photo: “IMG_1313” Oregon National Guard. State Partnership Program. Photo by CW3 Devin Wickenhagen is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonmildep/14573679193 Infrastructure Section Photo: “River scene in Bangladesh, 2008 Photo: AusAID” Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/dfataustralianaid/10717349593/ Health Section Photo: “Arsenic safe village-woman at handpump” by REACH: Improving water security for the poor is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/reachwater/18269723728 Women, Peace, and Security Section Photo: “Taroni’s wife, Baby Shikari” USAID Bangladesh photo by Morgana Wingard. https://www.flickr.com/photos/usaid_bangladesh/27833327015/ Conclusion Section Photo: “A fisherman and the crow” by Adnan Islam is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adnanbangladesh/543688968 Appendices Section Photo: “Water Works Road” in Dhaka, Bangladesh by David Stanley is licensed under CC BY 2.0. -

Armed Forces War Course-2013 the Ministers the Hon’Ble Ministers Presented Their Vision

National Defence College, Bangladesh PRODEEP 2013 A PICTORIAL YEAR BOOK NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE MIRPUR CANTONMENT, DHAKA, BANGLADESH Editorial Board of Prodeep Governing Body Meeting Lt Gen Akbar Chief Patron 2 3 Col Shahnoor Lt Col Munir Editor in Chief Associate Editor Maj Mukim Lt Cdr Mahbuba CSO-3 Nazrul Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Family Photo: Faculty Members-NDC Family Photo: Faculty Members-AFWC Lt Gen Mollah Fazle Akbar Brig Gen Muhammad Shams-ul Huda Commandant CI, AFWC Wg Maj Gen A K M Abdur Rahman R Adm Muhammad Anwarul Islam Col (Now Brig Gen) F M Zahid Hussain Col (Now Brig Gen) Abu Sayed Mohammad Ali 4 SDS (Army) - 1 SDS (Navy) DS (Army) - 1 DS (Army) - 2 5 AVM M Sanaul Huq Brig Gen Mesbah Ul Alam Chowdhury Capt Syed Misbah Uddin Ahmed Gp Capt Javed Tanveer Khan SDS (Air) SDS (Army) -2 (Now CI, AFWC Wg) DS (Navy) DS (Air) Jt Secy (Now Addl Secy) A F M Nurus Safa Chowdhury DG Saquib Ali Lt Col (Now Col) Md Faizur Rahman SDS (Civil) SDS (FA) DS (Army) - 3 Family Photo: Course Members - NDC 2013 Brig Gen Md Zafar Ullah Khan Brig Gen Md Ahsanul Huq Miah Brig Gen Md Shahidul Islam Brig Gen Md Shamsur Rahman Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Brig Gen Md Abdur Razzaque Brig Gen S M Farhad Brig Gen Md Tanveer Iqbal Brig Gen Md Nurul Momen Khan 6 Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army 7 Brig Gen Ataul Hakim Sarwar Hasan Brig Gen Md Faruque-Ul-Haque Brig Gen Shah Sagirul Islam Brig Gen Shameem Ahmed Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh -

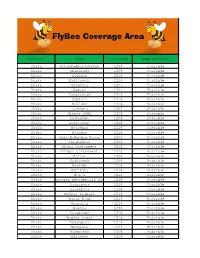

Flybee Coverage Area

FlyBee Coverage Area District Area Post Code Home Delivery Dhaka Mohammadpur(Dhaka) 1207 Possible Dhaka Dhanmondi 1209 Possible Dhaka Gulshan 1212 Possible Dhaka Kallyanpur 1216 Possible Dhaka Shyamoli 1207 Possible Dhaka Adabor 1207 Possible Dhaka Darussalam 1216 Possible Dhaka Gabtoli 1216 Possible Dhaka Pallabi 1216 Possible Dhaka Lalmatia 1207 Possible Dhaka Mirpur DOHS 1216 Possible Dhaka Kochukhet 1206 Possible Dhaka Gudaraghat 1212 Possible Dhaka Agargaon 1216 Possible Dhaka Monipur 1216 Possible Dhaka Sher-E-Bangla Nagar 1205 Possible Dhaka Ibrahimpur 1206 Possible Dhaka Dhaka Cantonment 1212 Possible Dhaka Mirpur Cantonment 1216 Possible Dhaka Kafrul 1206 Possible Dhaka Vashantek 1206 Possible Dhaka Manikdi 1216 Possible Dhaka Matikata 1216 Possible Dhaka M.E. -

A Professional Journal of National Defence College Volume 6 Number

A Professional Journal of National Defence College Volume 6 Number 1 June 2007 National Defence College Bangladesh EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Patron Lieutenant General Abu Tayeb Muhammad Zahirul Alam, rcds,psc Editor-in-Chief Air Commodore Mahmud Hussain, ndc, psc Associate Editors Captain M Anwarul Islam, (ND), afwc, psc, BN Lieutenant Colonel Md Abdur Rouf, afwc, psc Assistant Editor CSO-3 Md Nazrul Islam Editorial Advisors Dr. Fakrul Islam Ms. Shuchi Karim DISCLAMER The analysis, opinions and conclusions expressed or implied in this Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NDC, Bangladesh Armed Forces or any other agencies of Bangladesh Government. Statements of fact or opinion appearing in NDC Journal are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by the editors or publisher. ISSN: 1683-8475 INITIAL SUBMISSION Initial Submission of manuscripts and editorial correspondence should be sent to the National Defence College, Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka-1216, Bangladesh. Tel: 88 02 8059488, Fax: 88 02 8013080, Email : [email protected]. Authors should consult the Notes for Contributions at the back of the Journal before submitting their final draft. The editors cannot accept responsibility for any damage to or loss of manuscripts. Subscription Rate (Single Copy) Individuals : Tk 300 / USD 10 (including postage) Institutions : Tk 375 / USD 15 (including postage) Published by the National Defence College, Bangladesh All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electrical, photocopying, re- cording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Tuition Fees Collection of Through Trust Bank Payment Gateway

Payment No Physical From At Presence Anywhere Anytime Tuition Fees Collection of HALISHAHAR CANTONMENT PUBLIC SCHOOL & COLLEGE (HCPSC) through Trust Bank Payment Gateway Presented By Digital Financial Services Division About Trust Bank Limited Trust Bank Limited is one of the leading private commercial bank With a wide range of modern corporate and consumer financial products Have spread network of 110 Branches, 15000+ Agents, 210 own ATM and 1,500+ Shared ATM Booths and 10 T- Lobby across Bangladesh The bank, sponsored by the Army Welfare Trust, is first of its kind in the country. Trust Bank has been operating in Bangladesh since 1999 and has achieved public confidence as a sound and stable bank. Since 2007, Trust Bank successfully operating Online Banking Services which facilitate Any Branch Banking, ATM Banking, Phone Banking, SMS Banking, & Internet Banking Trust Bank has successfully introduced Visa Debit, Credit Cards to serve its existing and potential valued customers. In August 2010, the bank launched Trust Bank Mobile Financial Service Trust Bank has re-launched and rebranded Trust Bank Mobile Money as ‘t-cash’ effective from April 01, 2018. Clients: Educational Institutions Proyash RAJUK College Shaheed Anowar Adamjee Cantt. Bangladesh University Cadet College College Of Professionals Shaheed Dawood Public Dhaka Residential Rajshahi Bangladesh Navy Bandarban Cantonment Model College Ramiz Uddin Cantt.Public School and Public School & College School High School School & College College, Mongla & College Jessore Nirjhor -

The Internationalisation of Bangladeshi Military Intervention in 2007

The Internationalisation Of Bangladeshi Military Intervention In 2007 By M Mukhlesur Rahman Chowdhury 17 November, 2014 Countercurrents.org International relations have major role in governing different countries, particularly, in this era of globalisation. It is more evident in developing countries’ politics. Moreover, extra-constitutional government needs special support and attention from foreign powers for its legitimacy. Bangladesh witnessed military-backed government’s parley to gain international support during its tenure of 2007-08 period. The military rule contacted relevant international powerful quarters in order to receive their supports. Appointment of Dr. Fakhruddin Ahmed as the head of the government was nothing but first signal of military administration to show that they have international connections. On the one hand the military’s priority was Dr. Muhammad Yunus, and on the other hand, Yunus’s choice was different. He was more interested to be the head of the state or the President of the country. Instead of joining as head of the government or Chief Adviser during the army-backed regime Yunus made his all out efforts to start with a journey for his new political front ‘Nagarik Shakti’. However, that move has failed as people went against the military’s anti-political behaviour. Role of PR in UN Initially, Permanent Representative of Bangladesh in United Nations Dr. Iftekhar Ahmed Chowdhury was aspirant for the position of the Chief Adviser. After completion of his regular appointment in the United Nations as Permanent Representative, Iftekhar was discharging his contractual assignment in the same position in New York. In fact, he was the unofficial adviser of Army Chief Moeen Uddin Ahmed prior to 11 January 2007 military coup. -

Overseas Study Tour - ND Course 2019 the Three Weeks Overseas Study Tour Include Visit to Neighbouring, Developing and Developed Countries

National Defence College, Bangladesh NDC Newsletter Overseas Study Tour - ND Course 2019 The three weeks overseas study tour include visit to neighbouring, developing and developed countries. The aim of these tours is to examine the social, political, economic and military systems of those countries. The course members September-2019 meet high-ranking civil and military officials and visit government, military Volume-7, Issue-3 and industrial establishments to exchange views and opinions. The visits also promotes good relation between those countries and Bangladesh. This year Course Members of National Defence Course 2019 along with Faculty and Staff Officers visited 15 countries in five groups. Group - 1 visited India, Oman and Russia; Group - 2 visited Nepal, Kuwait and United Kingdom; Group - 3 visited The Editorial Board Thailand, Philippines and Australia; Group - 4 visited Vietnam, Turkey and Italy Chief Patron and Group - 5 visited Bhutan, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Switzerland. Lt Gen Sheikh Mamun Khaled SUP, rcds, psc, PhD Commandant, NDC Editor Lt Col Nizam Uddin Ahmed afwc, psc, Engr Acting Director (Research and Academic) Associate Editor Lt Col Muhammad Alamgir Iqbal Khan, psc, Arty Senior Research Fellow Assistant Editor Md Nazrul Islam Assistant Director ND Course-2019 visiting delegation (Group-4) at Vietnam during Overseas Study Tour. HIGHLIGHTS OF NDC ND Course-2019 04 July 2019: Lieutenant General Mohammad Overseas Study Tour (OST) Mahfuzur Rahman, OSP, rcds, ndc, afwc, psc, PhD, Principal Staff Officer, Armed Forces Division 19 July 2019-24 July 2019: Overseas Study Tour (OST)-1 04 August 2019: Lieutenant General Sheikh Mamun Khaled, SUP, rcds, psc, PhD, Commandant, NDC 08 September 2019-21 September 2019: Overseas Study Tour (OST)-2 LoCaL Visit-aFWC 2019 GUEst SPEAKERS 03 July 2019: Visit to Police Headquarters 11 July 2019: Dr. -

Search & Rescue Plan

Search and Rescue Plan Civil Aviation Authority of Bangladesh GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH SEARCH AND RESCUE PLAN ISSUE-1, 2018 PUBLISHED BY CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY OF BANGLADESH KURMITOLA, DHAKA Search and Rescue Plan Civil Aviation Authority of Bangladesh PREAMBLE The Search and Rescue Plan is issued by the Chairman, Civil Aviation Authority of Bangladesh in pursuance of the powers vested on him vide Civil Aviation Rule (CAR) 84, Art. 232 (1) & (2) and ANO (SAR) A-1 Chapter 4, Para 4.2.1. The Search and Rescue function is a State obligation imposed by the Convention on International Civil Aviation (Chicago Convention-1944).This document will serve as a reference for use by the Rescue Coordination Centre in the planning and execution of an Aeronautical Search and Rescue operation within the Search and Rescue Region (SRR) of Bangladesh. Search and Rescue in Bangladesh is provided under the joint collaboration of Civil Aviation Authority of Bangladesh, Bangladesh Army, Bangladesh Navy, Bangladesh Air Force, Bangladesh Marine Authorities, Bangladesh Coast Guard, Bangladesh Police, Border Guard Bangladesh and Other Civil Organisations when so requested. The purpose of this plan is to establish responsibility, authority, operational and administrative procedures for Aeronautical Search and Rescue activities within the boundaries of the Search and Rescue Region (SRR). The objective of this Plan is to give appropriate priority to the protection of human life, provide necessary care, including emergency medical care, and evacuate persons in distress using the most effective methods with least possible delay. PURPOSE To establish responsibility, authority, and operational and administrative procedures for Search and Rescue activities within the boundaries of Bangladesh.