Rethinking Aaja Nachle: Power, Learning, Tradition and Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeking Offense: Censorship and the Constitution of Democratic Politics in India

SEEKING OFFENSE: CENSORSHIP AND THE CONSTITUTION OF DEMOCRATIC POLITICS IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Ameya Shivdas Balsekar August 2009 © 2009 Ameya Shivdas Balsekar SEEKING OFFENSE: CENSORSHIP AND THE CONSTITUTION OF DEMOCRATIC POLITICS IN INDIA Ameya Shivdas Balsekar, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 Commentators have frequently suggested that India is going through an “age of intolerance” as writers, artists, filmmakers, scholars and journalists among others have been targeted by institutions of the state as well as political parties and interest groups for hurting the sentiments of some section of Indian society. However, this age of intolerance has coincided with a period that has also been characterized by the “deepening” of Indian democracy, as previously subordinated groups have begun to participate more actively and substantively in democratic politics. This project is an attempt to understand the reasons for the persistence of illiberalism in Indian politics, particularly as manifest in censorship practices. It argues that one of the reasons why censorship has persisted in India is that having the “right to censor” has come be established in the Indian constitutional order’s negotiation of multiculturalism as a symbol of a cultural group’s substantive political empowerment. This feature of the Indian constitutional order has made the strategy of “seeking offense” readily available to India’s politicians, who understand it to be an efficacious way to discredit their competitors’ claims of group representativeness within the context of democratic identity politics. -

Indian Police Journal for the Year 2016

The Indian Police Journal January-March, 2016 Vol. LXIII No. 1 EDITORIAL BOARD CONTENTS 1. Transforming Police into Smart Police 4 Shri N.R. Wasan, IPS Rajeev Tandon 2. “Ama Police”- The Community Policing 12 DG, BPR&D, MHA Scheme of Odisha Adviser Satyajit Mohanty 3. Human Rights, Police and Ethics: Towards 22 an Understanding of transforming the Shri Radhakrishnan Kini, IPS Police from a ‘Force’ to ‘Social Service’ SDG, BPR&D, MHA Dr. Harjeet S. Sohal 4. The Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 41 Editor-in-Chief 1958 – Urgency of Review Caesar Roy 5. A Requiem for Free Speech 68 Dr. Nirmal Kumar Azad, IPS Umesh Sharraf IG/Director (S&P) 6. Pragmatic Approach Towards Youths In 93 Editor 21st Century Amit Gopal Thakre 7. Right To Life Vis-À-Vis Death Penalty: 110 Shri B.S. Jaiswal, IPS Analyzing The Indian Position DIG/DD (S&P) Shakeel Ahmad and Tariq Ashfaq 8. The Women Victims of Alcohol Induced 124 Editor Domestic Violence and the Role of Community Police in Kerala: An Empirical Study Kannan. B, Dr. S. Ramdoss 9. Personality of Female Prisoners: An 145 Analytical Study Nouzia Noordeen, Dr. C. Jayan 10. A Correlational Study of PsyCap, EQ, 160 Hardiness and Job Stress in Rajasthan Police Officers Prof. (Dr). S.S Nathawat 11. Police Job’s Stressors: Does It Effect on the 170 Editor Job Performance, Quality of Life and Work of Police Personnel? Gopal K.N. Chowdhary Dr. Manoj Kumar Pandey 12. The People’s Friendly Police & 206 Community Policing K.N. Gupta 13. Police Response to Violence Against 229 Women in Punjab: Law, Policy & Practice Upneet Kaur Mangat 14. -

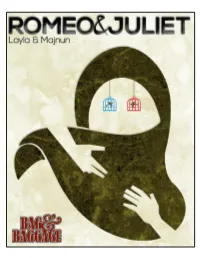

Layla and Majnun

Layla and Majnun also Leili o Majnun ,( ﻣﺠﻨﻮن ﻟﻴﻠﻰ :Layla and Majnun (Arabic is a narrative poem composed in 584/1188 ,( ﻟﻴﻠﻰ و ﻣﺠﻨﻮن :Persian) by the Persian poet Niẓāmi Ganjavi based on a semi-historical Arab story about the 7th century Nejdi Bedouin poet Qays ibn Al- Mulawwah and his ladylove Layla bint Mahdi (or Layla al- Aamiriya).[1][2][3][4] Nizami also wrote Khosrow and Shirin, a Persian tragic romance, in the 12th century. It is a popular poem praising their love story.[5][6][7] It is the third of his five long .(The Five Treasures) (ﭘﻨﺞ ﮔﻨﺞ :narrative poems, Panj Ganj (Persian Lord Byron called it “the Romeo and Juliet of the East.”[8] Qays and Layla fall in love with each other when they are young, but when they grow up Layla’s father doesn't allow them to be together. Qays becomes obsessed with her, and his tribe Banu Amir and the .crazy", lit" ﻣﺠﻨﻮن) community gives him the epithet of Majnūn "possessed by Jinn"). Long before Nizami, the legend circulated in anecdotal forms in Iranian akhbar. The early anecdotes and oral reports about Majnun are documented in Kitab al-Aghani and Ibn Qutaybah's al-Shi'r wal-Shu'ara'. The anecdotes are mostly very short, only loosely connected, and show little or no plot development. Nizami collected both secular and mystical sources about Majnun and portrayed a vivid picture of the famous lovers.[9] Subsequently, many other Persian poets imitated him and wrote their own versions of the romance.[9] Nizami drew influence from Udhrite love poetry, which is characterized by erotic abandon and attraction A miniature of Nizami's work. -

LIST of HINDI CINEMA AS on 17.10.2017 1 Title : 100 Days

LIST OF HINDI CINEMA AS ON 17.10.2017 1 Title : 100 Days/ Directed by- Partho Ghosh Class No : 100 HFC Accn No. : FC003137 Location : gsl 2 Title : 15 Park Avenue Class No : FIF HFC Accn No. : FC001288 Location : gsl 3 Title : 1947 Earth Class No : EAR HFC Accn No. : FC001859 Location : gsl 4 Title : 27 Down Class No : TWD HFC Accn No. : FC003381 Location : gsl 5 Title : 3 Bachelors Class No : THR(3) HFC Accn No. : FC003337 Location : gsl 6 Title : 3 Idiots Class No : THR HFC Accn No. : FC001999 Location : gsl 7 Title : 36 China Town Mn.Entr. : Mustan, Abbas Class No : THI HFC Accn No. : FC001100 Location : gsl 8 Title : 36 Chowringhee Lane Class No : THI HFC Accn No. : FC001264 Location : gsl 9 Title : 3G ( three G):a killer connection Class No : THR HFC Accn No. : FC003469 Location : gsl 10 Title : 7 khoon maaf/ Vishal Bharadwaj Film Class No : SAA HFC Accn No. : FC002198 Location : gsl 11 Title : 8 x 10 Tasveer / a film by Nagesh Kukunoor: Eight into ten tasveer Class No : EIG HFC Accn No. : FC002638 Location : gsl 12 Title : Aadmi aur Insaan / .R. Chopra film Class No : AAD HFC Accn No. : FC002409 Location : gsl 13 Title : Aadmi / Dir. A. Bhimsingh Class No : AAD HFC Accn No. : FC002640 Location : gsl 14 Title : Aag Class No : AAG HFC Accn No. : FC001678 Location : gsl 15 Title : Aag Mn.Entr. : Raj Kapoor Class No : AAG HFC Accn No. : FC000105 Location : MSR 16 Title : Aaj aur kal / Dir. by Vasant Jogalekar Class No : AAJ HFC Accn No. : FC002641 Location : gsl 17 Title : Aaja Nachle Class No : AAJ HFC Accn No. -

The Story of Laila and Majnun in Early Modern South Asia

Crazy in Love: The Story of Laila and Majnun in Early Modern South Asia The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hasson, Michal. 2018. Crazy in Love: The Story of Laila and Majnun in Early Modern South Asia. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41121211 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Crazy in Love: The Story of Laila and Majnun in Early Modern South Asia A dissertation presented by Michal Hasson To The Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the subject of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts June 2018 © 2018 Michal Hasson All rights reserved Dissertation Advisor: Prof. Ali Asani Michal Hasson Crazy in Love: The Story of Laila and Majnun in Early Modern South Asia Abstract This study explores the emergence and flourishing of several vernacular literary cultures in South Asia between the early seventeenth and late nineteenth centuries through one of the most popular love stories told across the Middle East, Persia, Anatolia, Central Asia, and South Asia: the story of Laila and Majnun. In South Asia, we find numerous versions of this love tale in all the major South Asian languages and in various genres and formats. -

Chandigarh, Quarters from August 16

' # >1 % ? " % ? " ? 23"/#24'5*16 *) . *.1 $*.!/0 %)*+,- # 34B#1B, 4,<1,543, 14<5<=)B; 5B<5=4-;3 #40-3C 353=3 51,35 #,5--5=,4 041-#40B30- 0B04=04<CE 0B3, 14531= 5C1431D9C;1 < $./01 22' ''@ A- 4 "" 7 & -8 Q %" % O P 4;14<5 4;14<5 India as well. oing back on their word mid reports claiming that The Delta variant is cur- Gnot to target embassies, the ATaliban’s supreme leader rently driving the pandemic Taliban in the last few days Haibatullah Akhundzada may be across several countries with entered consulates of India in the custody of the Pakistan China and Korea seeing new and ransacked these looking for Army and has not been seen highs. Korea has reported that documents. They later even during the last six months, the the new surge is due to Delta took away the parked cars security establishment here said 4;14<5 plus K417N mutation. from the premises. he could be very much in The Delta variant resulted These incidents were Afghanistan itself and could f the 30,230 samples of in a deadly second wave in the reported from the Kandahar arrive on the scene once the US Ovariants of concern and country between March and and Herat consulates from forces completely withdraw from variants of interest sequenced May that wreaked havoc on the where New Delhi has pulled the war-ravaged country on # $%& so far in India, a significant health infrastructure, over- out all its India-based diplo- embassies of some other coun- vehicles. -

Aaja Nachle 5 Full Movie Mp4 Free Downloadl

Aaja Nachle 5 Full Movie Mp4 Free Downloadl 1 / 4 Aaja Nachle 5 Full Movie Mp4 Free Downloadl 2 / 4 3 / 4 Madhuri Dixit's comeback film after Devdas which released 5 years ago. Aaja Nachle (2007) Watch Online Full Movie Free DVDRip, Watch And Download Aaja Nachle Movie Free, Latest HD 720P MP4 Movies Aaja Nachle .... FWatch Aaja Nachle HD Full . 5:35. Tholi Prema (2018) Hindi Dubbed Movie .. Music Videos ... Watch Aaja Nachle (2007) Full Movie Online HD Free Download in DVDRip and ... Download Ajaa video in hd 720p 1080p mp3 torrent mp4 free.. Home » Bollywood Music » Aaja Nachle (2007) Movie Mp3 Songs » O Re Piya. ... Track # Song Singer(s) Duration Picturised on 1 'Aaja Nachle' 5:04 2 'Ishq ... movie mp4 1080p 1.0GB extra kickass torrent free download hd .... The Rafta Rafta The Speed 2 Full Movie Mp4 Free Download ... Aaja Nachle 4 torrent download locations bt-scene.cc Aaja Nachle Movies 5 days ... Aaja Nachle Movies 5 days torrentdownloads.me Aaja Nachle Movies 4 .... Download Hungama Play app to get access to new unlimited free mp4 movies download, Sinhala movies 2019/2018/2017, latest music videos, kids movies, .... Year 3GP Mp4 HDRip Movies Free Download, Tamil 720p 1080p HDRip. ... Colok Memek ABG Amoy Pake Timun - Bokep Indonesia · 5 min. ... Aaja Nachle Mp3 Song Download by Sunidhi Chauhan from Bollywood Movie Aaja Nachle (2007) .... Brand New Movies - MP3 , MP4 , 3GP Free ... Reality Shows . ... Aaja Nachle Torrent Download Free . ... Download Film Scary Movie 1-5 Sub Indo. Mirza the .... Tag: Download Film silat ' WIRO SABLENG '.mp4 Mp3,,, film2 slat indonesia, .. -

Yash Raj Films (Yrf) - Filmography

YASH RAJ FILMS (YRF) - FILMOGRAPHY SR. NO. YEAR FILM DIRECTOR PRODUCER 1 1973 Daag Yash Chopra Yash Chopra 2 1976 Kabhi KabhiE Yash Chopra Yash Chopra 3 1977 Doosara Aadmi RamEsh Talwar Yash Chopra 4 1979 NooriE Manmohan Krishna Yash Chopra 5 1979 Kaala Patthar Yash Chopra Yash Chopra 6 1981 Nakhuda Dilip Naik Yash Chopra 7 1981 Silsila Yash Chopra Yash Chopra 8 1982 Sawaal RamEsh Talwar Yash Chopra 9 1984 Mashaal Yash Chopra Yash Chopra 10 1985 FaaslE Yash Chopra Yash Chopra 11 1988 Vijay Yash Chopra Yash Chopra 12 1989 Chandni Yash Chopra Yash Chopra 13 1991 Lamhe Yash Chopra Yash Chopra 14 1993 Aaina DeEpak SarEEn Yash Chopra 15 1993 Darr Yash Chopra Yash Chopra 16 1994 Yeh Dillagi NarEsh Malhotra Yash Chopra 17 1995 DilwalE Dulhania LE JayEngE Aditya Chopra Yash Chopra 18 1997 Dil To Pagal Hai Yash Chopra Yash Chopra 19 2000 MohabbatEin Aditya Chopra Yash Chopra 20 2002 MerE Yaar Ki Shaadi Hai Sanjay Gadhvi Yash Chopra 21 2002 MujhsE Dosti KarogE Kunal Kohli Yash Chopra 22 2002 Saathiya Shaad Ali Bobby Bedi 23 2004 Hum Tum Kunal Kohli Aditya Chopra 24 2004 Dhoom Sanjay Gadhvi Aditya Chopra 25 2004 VeEr-Zaara Yash Chopra Yash Chopra & Aditya Chopra 26 2005 Bunty aur Babli Shaad Ali Sahgal Aditya Chopra 27 2005 Salaam NamastE Siddharth Raj Anand Aditya Chopra 28 2005 Neal 'n' Nikki Arjun Sablok Aditya Chopra 29 2006 Fanaa Kunal Kohli Aditya Chopra 30 2006 Dhoom:2 Sanjay Gadhvi Aditya Chopra 31 2006 Kabul ExprEss Kabir Khan Aditya Chopra 32 2007 Ta Ra Rum Pum Siddharth Anand Aditya Chopra 33 2007 Jhoom Barabar Jhoom Shaad Ali Sahgal -

Haryana Floats Tender for Amphotericin-B Injection

WWW.YUGMARG.COM FOLLOW US ON REGD NO. CHD/0061/2006-08 | RNI NO. 61323/95 Join us at telegram https://t.me/yugmarg Thursday May 27, 2021 CHANDIGARH, VOL. XXVI, NO. 117 PAGES 12, RS. 2 YOUR REGION, YOUR PAPER HSAMB to follow Amarinder asks HC asks HP govt to Need to improve norms of HSIIDC Patiala DC to conduct covid my conversation testing on war- to auction speed up rate, says Anirudh footing shops, plots ongoing canal Thapa based water supply project PAGE 3 PAGE 4 PAGE 5 PAGE 11 Cyclone Yaas weakens Protest flags and marches as after pounding Odisha-Bengal coasts Gold rallies Rs farmers observe 'black day' AGENCY 527; silver BALASORE/DIGHA/RANCHI, MAY 26 zooms Rs 1,043 Tikait says will adhere to NEW DELHI: Gold rallied Yaas weakened into a severe cy- Rs 527 to Rs 48,589 per Covid-19 protocols clonic storm on Wednesday after- 10 grams in the national noon after pounding the beach NEW DELHI: As farmers in Ghaziabad on began capital on Wednesday re- towns in north Odisha and neigh- 'Black Day' protests on Wednesday to mark com- flecting gains in global bouring West Bengal with a wind pletion of six months of their agitation against precious metal prices, ac- speed of 130-145 kmph, inundat- Centre's agricultural laws, the Bharatiya Kisan cording to HDFC Securi- ing the low-lying areas amid a blocks in the Balasore district, and Union spokesperson Rakesh Tikait assured that ties. In the previous storm surge even as the two east- Dhamra and Basudevpur in the the protests will be carried out peacefully in ad- trade, the precious metal herence to Covid-19 protocols. -

Nepali Times

#380 28 December 2007 - 3 January 2008 18 pages Rs 30 Weekly Internet Poll # 380 Q. If elections aren’t held in Chait, whose fault will it be? Will 2008 be any different? Total votes: 6,279 Weekly Internet Poll # 381. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com Q.Will elections happen this time? JANUARY 2007 FEBRUARY MARCH APRIL The tarai ignites. UNMIN begins Kathmandu dithers on the madhes. Gaur massacre. The June date for First anniversary of the April work in cantonments. People wait for the peace dividend elections looks doubtful. Uprising marked by continued that never arrives. political deadlock. MAY JUNE JULY AUGUST Gas, water, electricity shortages Support for monarchy at all time YCL excesses intensify, Maoists Maoist plenum puts pressure on highlight state incompetence. low. The Maoists aren’t much get unions to close down leaders to delay elections. popular either. newspapers. SEPTEMBER OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER Maoists walk out of government, EC gears up for polls again, but NC and Maoists still can’t find Maoists back in government, peace process in disarray. politicians get cold feet. a compromise. elections in April. Public skeptical. 2 EDITORIAL 28 DECEMBER 2007 - 3 JANUARY 2008 #380 Published by Himalmedia Pvt Ltd, Editor: Kunda Dixit Design: Kiran Maharjan Director Sales and Marketing: Sunaina Shah marketing(at)himalmedia.com Circulation Manager: Samir Maharjan sales(at)himalmedia.com Subscription: subscription(at)himalmedia.com,5542525/535 The year of the madhes Hatiban, Godavari Road, Lalitpur editors(at)nepalitimes.com GPO Box 7251, Kathmandu 5543333-6, Fax: 5521013 www.nepalitimes.com Printed at Jagadamba Press, Hatiban: 5547018 2007 transformed the tarai, Nepal will never be the same again PEACE TRAIN he last week of 2007 granted, commits political even as a bargaining chip as Nepali lefties have always had a flair for pompous rhetoric. -

RJ-LM-Guide-Min.Pdf

STUDY GUIDE CONTENTS Introduction ROMEO&JULIET Romeo & Juliet (LAYLA&MAJNUN) Layla & Majnun Based on The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare Our Production With adapted text from Layla and Majnun by Nizami Ganjavi Who’s Who? Adapted by Scott Palmer Themes With translation assistance from Melory Mirashrafi Discussion Questions & Directed by Scott Palmer Writing Activities Sources & July 20 - August 5, 2017 Further Reading The Hillsboro Civic Center Plaza CAST Romeo/Majnun (a Bedouin youth) ...................................... Nicholas Granato BAG&BAGGAGE STAFF The Sayyid (Romeo’s father, a descendant of Muhammad) ......... Lawrence Siulagi Scott Palmer Benvolia (cousin to Romeo, a Bedouin) ....................................... Cassie Greer* Artistic Director Nawfal/Mercutio (a Bedouin warrior) ............................................ Colin Wood Beth Lewis Abram (a Bedouin youth, also a singer) ................................... Avesta Mirashrafi Managing Director Ibn Salam/Paris (a Bedouin trader) ............................................ Eric St. Cyr** Cassie Greer Juliet/Layla (a Roman lady) ................................................ Arianne Jacques* Associate Artistic Director Lady Capulet (Juliet’s mother, emissary of Constantine) .. Mandana Khoshnevisan Arianne Jacques Tybalt (cousin to Juliet, a Warrior of the Cross) ............................... Signe Larsen Patron Services Manager A Storyteller ............................................................................. -

Yash Raj Films: from Print to Digital Platform

Yash Raj Films: From Print to Digital Platform Neha Agarwal1 and Pooja Agarwal2 1,2Kirloskar Institute of Advanced Management Studies, Pune “In our business today, the most valuable currency the audience has is their TIME. And they are very sure about how they want to trade it. Also, it’s no longer enough just to create buzz about the product, it’s now more important to compete for their attention by providing compelling reasons to experience our product.” 1 —Yash Raj Film’s Statement on its Website As the rainy season finally hits the skies of Mumbai, popularly known as The City of Dreams, it is the place in India where a lot of people come every day wishing to convert their dreams into reality. Yash Chopra, one of the leading film producers of pdf, India was carefully watching the rain drops on the window pane of his office. He has this been instrumental in shaping the symbolism of mainstreamof Hindi cinema across the globe. His company had a great name in the Bollywood filmcopyright-holder industry, from making content high-budget blockbusters to youth-oriented films,system, fromthe working with the biggest of actors of the industry to launching young talentany in films, Yash Raj films had by far applied a lot of marketing strategies to drawsave its retrieval customer’s attention. or But today the scenario was different, He wasany actually thinking about the crises that his film making company “Yash Raj printFilms” on PERMISSION was facing at that point of time in early full, 2007. That year, expensive filmscopy, likein JhoomBarabarJhoom with Amitabh Bachchan, to or Abhishek Bachchan, Preity Zinta andWRITTEN Lara Dutta, Aaja Nachle with Madhuri Dixit and Laaga Chunari Mein Daag partwith Rani Mukherjee had bombed in the market.