Adam Ahlgrim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{FREE} the Confidential Agent: an Entertainment

THE CONFIDENTIAL AGENT: AN ENTERTAINMENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Graham Greene | 272 pages | 22 Jan 2002 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099286196 | English | London, United Kingdom The Confidential Agent: An Entertainment PDF Book Graham Greene. View all 3 comments. I am going to follow this up with The Heart of the Matter. Neil Forbes Holmes Herbert This edition published in by Viking Press in New York. This wistful romance is one of Greene's other masterstrokes of plotting; he is refreshingly unabashed about any pig-headed question of decency and he lets this romance flow in seamlessly and incidentally into the narrative to lend it a real heart of throbbing passion. Shipping to: Worldwide. Buy this book Better World Books. Seller information worldofbooksusa Not in Library. Clear your history. The confidential agent: an entertainment , The Viking Press. In a small continental country civil war is raging. It has a fast-moving plot, reversals of fortune, and plenty of action. It is not exactly foiling a diabolical conspiracy perpetuated by a grand, preening super-villain or sneaking behind enemy lines. Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? The Power And The Glory was a deliberate exercise in exploring religion and morality, and Greene did not expect it to sell very well. Edit Did You Know? Well, it is. So, despite a promising start and interesting plot, the story itself loses grip on a number of occasions because there is little chemistry, or tension, between the characters - not between D. So he writes this book in the mornings, then writes the "serious" novel in the afternoons; whilst helping dig trenches on London's commons with the war looming. -

Moral Values in Espionage Novels by Graham Greene

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Viktoria Fedorova Moral Values In Espionage Novels by Graham Greene Bachelor's Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. 2017 / declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. Viktória Fedorová 2 Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, Stephen Paul Hardy, PhD. for all his valuable advice. I would also like to thank my family, my partner and my friends for their support. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 5 2. Graham Greene: Life and Vision 10 2.1. Espionage 15 2.2. Greene and Catholicism 17 2.3. The Entertainments and "Serious Novels" 21 3. The Ministry of Fear 23 4. The Quiet American 32 5. The Comedians 46 6. Conclusion °1 7. Works Cited 65 8. Resume (English) 67 9. Resume (Czech) 68 4 1. Introduction The aim of this thesis is to analyse and compare the treatment of moral values in three espionage novels by Graham Greene- The Ministry of Fear, The Quiet American and The Comedians- to show that the debate of moral values in Greene's novels is closely connected with the notion that the gravity of sins committed is connected to the amount of pain one's decision causes to other human beings. The evil committed by his characters is to be judged individually and one of his characters' greatest fears is the fear to cause the pain to other human beings. Espionage novels were used because Greene's experience with espionage is often projected into his novels and it is often central to the plot. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

The Destructors Graham Greene

The Destructors Graham Greene Online Information For the online version of BookRags' The Destructors Premium Study Guide, including complete copyright information, please visit: http://www.bookrags.com/studyguide-destructors/ Copyright Information ©2000-2007 BookRags, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. The following sections of this BookRags Premium Study Guide is offprint from Gale's For Students Series: Presenting Analysis, Context, and Criticism on Commonly Studied Works: Introduction, Author Biography, Plot Summary, Characters, Themes, Style, Historical Context, Critical Overview, Criticism and Critical Essays, Media Adaptations, Topics for Further Study, Compare & Contrast, What Do I Read Next?, For Further Study, and Sources. ©1998-2002; ©2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design® and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Encyclopedia of Popular Fiction: "Social Concerns", "Thematic Overview", "Techniques", "Literary Precedents", "Key Questions", "Related Titles", "Adaptations", "Related Web Sites". © 1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Guide to Literature for Young Adults: "About the Author", "Overview", "Setting", "Literary Qualities", "Social Sensitivity", "Topics for Discussion", "Ideas for Reports and Papers". © 1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. All other sections in this Literature Study Guide are owned and copywritten by BookRags, Inc. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. -

Introduction

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Graham Greene (ed.), The Old School (London: Jonathan Cape, 1934) 7-8. (Hereafter OS.) 2. Ibid., 105, 17. 3. Graham Greene, A Sort of Life (London: Bodley Head, 1971) 72. (Hereafter SL.) 4. OS, 256. 5. George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (London: Gollancz, 1937) 171. 6. OS, 8. 7. Barbara Greene, Too Late to Turn Back (London: Settle and Bendall, 1981) ix. 8. Graham Greene, Collected Essays (London: Bodley Head, 1969) 14. (Hereafter CE.) 9. Graham Greene, The Lawless Roads (London: Longmans, Green, 1939) 10. (Hereafter LR.) 10. Marie-Franc;oise Allain, The Other Man (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 25. (Hereafter OM). 11. SL, 46. 12. Ibid., 19, 18. 13. Michael Tracey, A Variety of Lives (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 4-7. 14. Peter Quennell, The Marble Foot (London: Collins, 1976) 15. 15. Claud Cockburn, Claud Cockburn Sums Up (London: Quartet, 1981) 19-21. 16. Ibid. 17. LR, 12. 18. Graham Greene, Ways of Escape (Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys, 1980) 62. (Hereafter WE.) 19. Graham Greene, Journey Without Maps (London: Heinemann, 1962) 11. (Hereafter JWM). 20. Christopher Isherwood, Foreword, in Edward Upward, The Railway Accident and Other Stories (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) 34. 21. Virginia Woolf, 'The Leaning Tower', in The Moment and Other Essays (NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974) 128-54. 22. JWM, 4-10. 23. Cockburn, 21. 24. Ibid. 25. WE, 32. 26. Graham Greene, 'Analysis of a Journey', Spectator (September 27, 1935) 460. 27. Samuel Hynes, The Auden Generation (New York: Viking, 1977) 228. 28. ]WM, 87, 92. 29. Ibid., 272, 288, 278. -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

THE HEART of the MATTER by Graham Greene

THE HEART OF THE MATTER by Graham Greene THE AUTHOR Graham Greene (1904-1991) was born in Berkhamsted, England. He had a very troubled childhood, was bullied in school, on several occasions attempted suicide by playing Russian roulette, and eventually was referred for psychiatric help. Writing became an important outlet for his painful inner life. He took a degree in History at Oxford, then began work as a journalist. His conversion to Catholicism at the age of 22 was due largely to the influence of his wife-to-be, though he later became a devout follower of his chosen faith. His writing career included novels, short stories, and plays. Some of his novels dealt openly with Catholic themes, including The Power and the Glory (1940), The Heart of the Matter (1948), and The End of the Affair (1951), though the Vatican strongly disapproved of his portrayal of the dark side of man and the corruption in the Church and in the world. Others were based on his travel experiences, often to troubled parts of the world, including Mexico during a time of religious persecution, which produced The Lawless Roads (1939) as well as The Power and the Glory, The Quiet American (1955) about Vietnam, Our Man in Havana (1958) about Cuba, The Comedians (1966) about Haiti, The Honorary Consul (1973) about Paraguay, and The Human Factor (1978) about South Africa. Many of his novels were later made into films. Greene was also considered one of the finest film critics of his day, though one particularly sharp review attracted a libel suit from the studio producing Shirley Temple films when he suggested that the sexualization of children was likely to appeal to pedophiles. -

The Modern World Through the Luminous Path of Prose Fiction: Reading Graham Greene’S a Burnt-Out Case and the Confidential Agent As Dystopian Novels

Nebula 6.2 , June 2009 The Modern World through the Luminous Path of Prose Fiction: Reading Graham Greene’s A Burnt-out Case and The Confidential Agent as Dystopian Novels. By Ayobami Kehinde What an absurd thing it was to expect happiness in a world so full of misery…. Point me out the happy man and I will point you out either egotisms, evil - or else an absolute ignorance (Graham Greene, The Heart of the Matter, 1948: 117) Graham Greene was undoubtedly one of the most gifted and acclaimed novelists of the War/Post-war era in Britain. His novels reflect a constant search for new novelistic modes of expression capable of visualizing the disillusionment and malaise of the modern world. According to Waldo Clarke (1976), an enduring trait of Greene’s fiction is the willingness to look at the repulsive face of the twentieth century. Since literature mostly reflects the mood of its age and enabling contexts, Greene’s fiction dwells on the conflicts and pains of the modern world. The central burden of this discourse is to prove that Greene’s novels steadily progressed in his bold use of the convention of dystopian fiction. It has been proved elsewhere that Greene’s The Power and the Glory and The Heart of the Matter are quintessential existential dystopian novels (See: Ayo Kehinde, 2004). However, in this present paper, an attempt is made to study more closely the dystopian features and political and ideological implications of the deployment of this convention in Greene’s The Confidential Agent and A Burnt-out Case . -

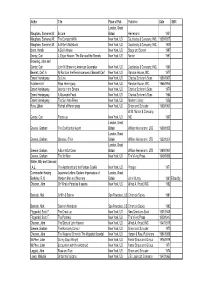

Eng Book2002

Author Title Place of Pub. Publisher Date ISBN London, Great Maugham, Somerset W. Encore Britain Heinemann 1951 Maugham, Somerset W. The Constant Wife New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1926/1927 Maugham, Somerset W. A Writer's Notebook New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1949 Ibsen, Henrik A Doll's House New York, US Stage and Screen 1997 Gentry, Curt J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets New York, US Norton 1991 Browning, John and Gentry, Curt John M. Browning American Gunmaker New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1964 Bennett, Cerf. A At Random the Reminiscences of Bennett Cerf New York, US Random House, INC. 1977 Ernest Hemingway By Line New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1956/1967 Hotchner A.E. Papa Hemingway New York, US Random House, INC. 1955/1966 Ernest Hemingway Islands in the Stream New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1970 Ernest Hemingway A Moveable Feast New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1964 Ernest Hemingway The Sun Also Rises New York, US Modern Library 1926 Ross, Lillian Portrait of Hemingway New York, US Simon and Schuster 1950/1961 W.W. Norton & Company, Gentry, Curt Frame-up New York, US INC 1967 London, Great Greene, Graham The Confidential Agent Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1939/1952 London, Great Greene, Graham Stamboul Train Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1932/1951 London, Great Greene, Graham A Burnt-Out Case Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1960/1961 Greene, Graham The 3rd Man New York, US The Viking Press 1949/1950 Wilder, Billy and Diamond, I.A.L. The Apartment and the Fortune Cookie New York, US Praeger 1971 Commander Hasting Japanese Letters: Eastern Impressions of London, Great Berkeley, R.N. -

The Mystery of Evil in Five Works by Graham Greene

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 The Mystery of Evil in Five Works by Graham Greene Stephen D. Arata College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Arata, Stephen D., "The Mystery of Evil in Five Works by Graham Greene" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625259. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-6j1s-0j28 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Mystery of Evil // in Five Works by Graham Greene A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Stephen D. Arata 1984 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts /;. WiaCe- Author Approved, September 1984 ABSTRACT Graham Greene's works in the 1930s reveal his obsession with the nature and source of evil in the world. The world for Greene is a sad and frightening place, where betrayal, injustice, and cruelty are the norm. His books of the 1930s, culminating in Brighton Rock (1938), are all, on some level, attempts to explain why this is so. -

1 Ministry of Fear 1-153 6/11/13, 10:29 Am Introduction

THE MINISTRY OF FEAR AN ENTERTAINMENT Grahame Greene Introduction by richard greene Coeor’s LıBrarY 3 1 Ministry of Fear 1-153 6/11/13, 10:29 am Introduction Spies, fugitives, double-agents, traitors, informers: Graham Greene seemed to carry these stock characters of fiction inside his skin. His imagination endowed them with moral urgency. He found in the plots of the common thriller, its concealments and duplicities, the elements of a more universal tale. His characters become the agents of the divided heart and their yearning for safety, escape, refuge, becomes a fable of the modern world. Graham Greene’s childhood would have divided any heart. Born in 1904, he was the son of a master (later headmaster) of Berkhamsted School in Hert- fordshire. After a quiet childhood, he was sent at the age of thirteen to live as a boarder in the school. This placed him on the other side of a symbolic green baize door which separated the family quarters from the school. The other boys assumed he was a Judas, reporting to his father all that happened in the dormitory. Two of his friends subjected him to elaborate mental cruelties, which he recalled as torture. Greene fell apart, made attempts at suicide, and eventually ran away to Berkhamsted Common, intending to become, as he wrote in his autobio- graphy, A Sort of Life (1971), ‘an invisible watcher, a spy on all that went on’. His parents brought him back into the family quarters, but he was never the same. In a family with a devastating history of mental illness, he showed signs of depression and instability. -

Proquest Dissertations

A THESIS ON GRAHAM GREENS MASTER IN THE FICTIONAL STUDY OF EVIL By Sister Sadie Hedwig Neumann, S.G.M. Thesis presented to the Faculty of Arts of the TJniversity of Ottawa in view to obtaining the degree of Master of Arts. mmjw Saint Norbert, Manitoba, 1951 UMI Number: EC55492 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform EC55492 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ACKNOWLEDGMENT This thesis has been prepared under the direction of Reverend Father Rene Lavigne, O.M.I., Dean of the Faculty of Arts. The technique has been submitted to Mr. George Buxton, M.A., D.Lit., Director of the Department of English Literature, of the Faculty of Arts, University of Ottawa. To all who have offered their kind co-operation, we wish to express our thanks. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter page INTRODUCTION iv I.- BIOGRAPHY 1 Principal Works 8 II.- CATHOLIC PHILOSOPHY IN FICTION 9 III.- WRITING TECHNIQUE 16 IY.- INTERPRETATION OF OUR TIMES 26 V.- THE MAN WITHIN 41 71.- LESSER WORKS 52 1.