Historic Structures Management Plan and Environmental Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

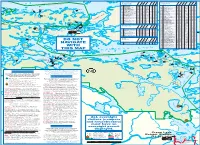

Do Not Navigate with This

Sand Point/ Namakan Crane Lake Lake TYPE TABLE TYPE TENT PAD FIRE RING ACCESS FOOD LOCKER TABLE PRIVY TENT PAD FIRE RING ACCESS FOOD LOCKER PRIVY S1 Brown’s Bay SC 2 1 Soft 0 1 1 N1 Birch Cove Island SC 0 1 Sand 1 1 1 S2 Brown’s Bay HB 0 1 Soft 0 0 0 N3 Leach Bay SC 2 1 Sand 1 1 1 R58 S3 Brown’s Bay View LC 4 1 Dock 2 2 1 N4 Cove Bay SC 0 1 Sand 1 1 1 N6 Deep Slough HB 0 1 Sand 0 0 0 R56 R3 S4 Burnt Island SC 2 1 Dock 1 1 1 eary S5 Feldt Channel SC 2 1 Soft 1 1 1 N7 Depthfinder Island SC 2 1 Dock 1 1 1 R27 R19 R13 S6 Granite Cliff North SC 2 1 Sand 1 1 1 N8 Depthfinder View HB 0 1 Sand 0 0 0 Lake R14 R25 S7 Granite Cliff South SC 2 1 Dock 1 1 1 N9 Ebel’s HB 0 1 Sand 0 0 0 S8 Grassy Bay HB 0 1 Soft 0 0 0 N10 Fox Island SC 0 1 Sand 0 1 1 R32 R33 S9 Houseboat Island West SC 2 1 Sand 1 1 1 N11 Hamilton Island East SC 0 1 Sand 1 1 1 Anderson Bay S10 King Pin LC 4 1 Dock 2 2 1 N12 Hoist Bay SC 2 1 Dock 1 1 1 S11 King Williams Narrows SCG 10 5 Dock 5 5 1 N13 Johnson Bay SC 2 1 Rock 1 1 1 N14 Junction Bay SC 0 1 Rock 1 1 1 d S12 Mukooda Lake SCG 0 5 Dock 5 5 1 n N15 Catamaran SC 0 1 Dock 0 1 1 a S13 North Island West SC 0 1 Soft 1 1 1 l S14 Norway Island LC 4 1 Sand 2 2 1 N16 Kettle Portage SC 2 1 Dock 1 1 1 Is Ryan B18 t l S15 Reef Island SC 2 1 Sand 1 1 1 N17 McManus Island HB 0 1 Sand 0 0 0 n e N18 McManus Island West SC 2 1 Dock 1 1 1 Lake i n S16 Sand Point Island East HB 0 1 Sand 0 0 0 o n S17 South Island SC 2 1 Rock 1 1 1 N19 Mica Bay Beach HB 0 1 Sand 0 0 0 P a S18 Stoneburner Island SC 2 1 Soft 1 1 1 N20 Mica Island SC 2 1 Dock 1 1 1 B2 k h N21 Mitchell Bay HB 0 1 Sand 0 0 0 a C S19 Wolf Island SC 2 1 Dock 1 1 1 N22 Mitchell Island West HB 0 1 Sand 0 0 0 O S20 N.W. -

Kettle Falls Hotel

FE: Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE 1 NTERIOR STA " (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Minnesota cou NTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORI C PLACES St. Louis : ORM INVENTORY - NOMINATION F FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTF*Y DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) JA^f 1 1 1975 ::::SO:::£8P^ COMMON: S'i'f -' 'g ' \ 'V-*-'-~"* \ ?. —-^ 1 ~t~~Ji * v^^ ^ ,' • Kettle Falls Hotel AND/OR HISTORIC: — /y^EiiiVED x|; Kettle Falls Hotel 111 ig^iidpyy)^^ STREET AND NUMBER: •£- tf~4 fe(&JL> o*"^ " 'H-®--*- '-."A NATIONAL i Sectiori? 33, T70N, R48W \^x REGISTER x^J CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICTv/>,, j <^V Ray /\s-*~£* , Eig]tith ^^^TpyTV ^ STATE CODE COUNTY: ~x— *— — ; — -— CODE Minnesota 22 . St. Louis 137 ||||l|i||||ilPllill;: -' I •&:;% ;;: •?£$ CATEGORY STATUS ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Q District [^ Building O Public Public Acquisition: g1 Occupied Yes: i M .j D Restricted D Site Q Structure 0 Private Q In Process r- j Unoccupied -, _. , [23 Unrestricted D Object | | Both JJ2JJ Being Considered pJ Preservation work in progress ' — ' PRESENT USE •' Jheck One or More as Appropriate; 1 1 Agricultural 1 1 Government 1 1 Park n T ransportation 1 1 Comments (X) Commercial [~~1 Industrial | | Privc ite Residence | | Ol her rSoecift,! Hotel O Educational L~H Military Q Relic)ious f~) Entertainment CD Museum | | Scieritific OWNER'S NAME: STATE- Charles Williams Minnesota STREET AND NUMBER: 622 - 12th Avenue CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODF International Falls Minnesota 22 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: COUNTY: St. Louis County Courthouse - Registry of Deeds St.Louis STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: STATE CODE Ely Minnesota 22 ^ TITLE OF SURVEY: Statewide Historic Sites Survey NUMBER^,ENTRY -n O DATE OF SURVEY: 9/6/74 O Federal ££] State Q County Q Local 73 DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: fe Z Y* 1J CO \S C Minnesota Historical Societv </> STREET AND NUMBER: m O Building 25, Fort Snelling r-z CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODE -< St. -

The Logging Era at LY Oyageurs National Park Historic Contexts and Property Types

The Logging Era at LY oyageurs National Park Historic Contexts and Property Types Barbara Wyatt, ASLA Institute for Environmental Studies Department of Landscape Architecture University of Wisconsin-Madison Midwest Support Office National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska This report was prepared as part of a Cooperative Park Service Unit (CPSU) between the Midwest Support Office of the National Park Service and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The grant was supervised by Professor Arnold R. Alanen of the Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and administered by the Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Wisconsin Madison. Cover Photo: Logging railroad through a northern Minnesota pine forest. The Virginia & Rainy Lake Company, Virginia, Minnesota, c. 1928 (Minnesota Historical Society). - -~------- ------ - --- ---------------------- -- The Logging Era at Voyageurs National Park Historic Contexts and Property Types Barbara Wyatt, ASLA Institute for Environmental Studies Department of Landscape Architecture University of Wisconsin-Madison Midwest Support Office National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 1999 This report was prepared as part of a Cooperative Park Service Unit (CPSU) between the Midwest Support Office of the National Park Service and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The grant was supervised by Professor Arnold R. Alanen of the Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and administered by the Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison. -

Rainy River-Headwaters Watershed Is Undeveloped and Utilized for Timber Production, Hunting, Fishing, Hiking, and Other Recreational Opportunities (MPCA 2017)

Rainy River - Headwaters August 2021 Draft Rainy River - Headwaters Watershed Restoration and Protection Strategy Report Authors Moriya Rufer, HEI Scott Kronholm, HEI Nathaniel Baeumler, HEI Jeremiah Jazdzewski, HEI Section 2.5.4, Drinking Water Protection, provided by MDH Edits by Amy Mustonen, MPCA Contributors/acknowledgements MPCA BWSR 1854 Treaty Authority Amy Mustonen Erin Loeffler Tyler Kaspar Jenny Jasperson Jeff Hrubes Angus Vaughn Lake County SWCD Jesse Anderson MDH Tara Solem Nate Mielke Chris Parthun Emily Nelson Ben Lundeen Tracy Lund Derrick Passe Mel Markert Sonja Smerud USFS Theresa Sagan DNR Marty Rye Ben Nicklay Darren Lilja North St. Louis SWCD Edie Evarts Emily Creighton Phil Norvitch Kevin Peterson Jason Butcher Becca Reiss Brent Flatten Anita Provinzino Dean Paron Voyageurs National Park Karl Koller Ryan Maki Cook County SWCD Sam Martin Ilena Hansel Cliff Bentley Taylor Nelson Vermilion Community College Anna Hess Wade Klingsporn Richard Biemiller Tom Burri Steve Persons Kim Boland Editing and graphic design PIO staff Graphic design staff Administrative Staff Cover photo: Kawishiwi Falls, Ely, MN Scott Kronholm, HEI Document number: wq-ws4-87a Contents List of Figures ........................................................................................................................................ i Executive summary ............................................................................................................................ vii 1. Watershed background and description ...................................................................................... -

Jun Fujita Cabin

NFS Form 10-900 ———'——————————— f _____ 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Inter National Park Service National Register of Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for not applicable." F9r functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategpries from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Fujita, Jun Cabin other names/site number Sackett Cabin, Wendt Cabin 2. Location street & number Wendt Island, Voyageurs National Park (VOYA) CD not for publication city or town Ranier X vicinity state Minnesota code MN county St. Louis code 137 zip code 56668 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this Gu nomination LJ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property D meets D does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant LJ nationally LJ statewide Q locally. -

Kettle Falls Site Development Plan Updated February, 2020

fishermen, trappers, and traders. As commercial The National Park Service is fishing declined over the years, tourists became preparing a plan for the Kettle Falls the hotel’s primary patrons. area of Voyageurs National Park Today, the Kettle Falls Historic District is on the National Register of Historic Places and remains a popular destination for tourists in Voyageurs Voyageurs NP Background National Park with its several docks, scenic trails, and lodging options. The historic Kettle Falls Hotel Voyageurs National Park encompasses 218,054 and adjacent villas operate from late May through acres of land and water along the Canadian border mid-September, and are the only lodging available in northern Minnesota. The park was established in in Voyageurs National Park. Some features of the 1975 with a mission to preserve, protect, and Kettle Falls area do not meet universal accessibility enhance resources in the Rainy, Kabetogama, standards and some structures in the area are in Namakan, and Sand Point Lakes areas. need of improvements. Voyageurs is a water-based park. The main body of land within the park’s boundary, the Kabetogama Peninsula, is only accessible by boat, seaplane, or snowmobile. Kettle Falls Background Kettle Falls is located at the end of the Kabetogama Peninsula. The area has been used by various peoples throughout history. Native Americans once gathered and hunted at the falls, voyageurs paddled and portaged through the area with their goods and furs, and prospectors stopped at the falls on their way to gold mines at Rainy Lake. Map of Kettle Falls area. Credit: NPS Plan Purpose The purpose of the Kettle Falls Site Development Plan is to enhance the visitor and employee experience in the Kettle Falls area. -

National Park System Properties in the National Register of Historic Places

National Park System Properties in the National Register of Historic Places Prepared by Leslie H. Blythe, Historian FTS (202) 343-8150 January, 1994 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Cultural Resources Park Historic Architecture Division United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE P.O. Box 37127 Washington, D.C. 20013-7127 H30(422) MAR 3 11994 Memorandum To: Regional Directors and Superintendents r From: Associate Director, Cultural Resources Subject: MPS Properties in the National Register of Historic Places Attached for your information is an updated list of properties within the National Park System listed in the National Register of Historic Places. National Historic Landmark status, documentation status, dates, and the National Register database reference number are included. This list reflects changes within 1993. Information for the sections Properties Determined Eligible by Keeper and Properties Determined Eligible by NPS and SHPO is not totally available in the Washington office. Any additional information for these sections or additions, corrections, and questions concerning this listing should be referred to Leslie Blythe, Park Historic Architecture Division, 202-343-8150. Attachment SYMBOLS KEY: Documentation needed. Documentation may need to be revised or updated. (•) Signifies property not owned by NPS. Signifies property only partially owned by NPS (including easements). ( + ) Signifies National Historic Landmark designation. The date immediately following the symbol is the date that the property was designated an NHL (Potomac Canal Historic District (+ 12/17/82) (79003038). Some properties designated NHLs after being listed will have two records in the NR database: one for the property as an historical unit of the NPS, the other for the property as an NHL. -

Publication Plan, Voyageurs National Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Voyageurs Voyageurs National Park Publication Plan 2009 PUBLICATION PLAN Voyageurs National Park 2009 Prepared by: The Interpretive Staff at Voyageurs National Park This Publication Plan (PL) provides a vision for the future of publication materials at Voyageurs National Park. The intended life span of the PL is five to ten years. The plan defines why we provide the publication materials that we do, describes the current publication materials, and identifies what the park staff is working to achieve for publications in the future. Table of Contents Page # Part 1: Introduction Foundation for Planning 3 Park Setting 3- 4 Legislative Background 5 Park Mission 5 Park Purpose 6 Park Significance 7 Interpretive Stories 8- 11 Interpretive Themes 12 Basis for Publications 13 Part 2: Partnerships Park Partners 14- 15 Resource Partners 16 Part 3: Audiences Identified 17 Part 4: Produced Publications Free Publications Produced by Voyageurs National Park 18- 20 Free Publications Produced by Partners, Associations and Concessionaires 21 Free Publications Produced by Other Organizations 22- 25 Publications for Sale in the Sales Outlets within Voyageurs National Park 26- 27 Part 5: Publications Categorized by Audience 28- 34 Part 6: Proposed Publications 35- 36 Part 1: Introduction Foundation for Planning This Publication Plan (PP) defines why Voyageurs National Park provides publication materials, describes the current publication, and identifies what the park is working to achieve in the future. This plan is connected to the General Management Plan (2001), and the Long Range Interpretive Plan (2005). Park Setting Voyageurs National Park is a land and water environment of great beauty, exceptional natural and cultural resources, and abundant recreation opportunities. -

PILLOWS/BLANKETS There Are No Pillows Or Blankets Provided on ANY Houseboat Due to Covid-19 and Minnesota DNR Restrictions

Hello from Ebel's! Our 2021 season is ahead of us and we have a few new policies and reminders that we would like to make our guests aware of. Please read and share this with your party prior to arrival to make any plans that may affect your vacation. Please read the Covid-19 policy as it may affect some items that are no longer provided on the houseboat. This policy will stay in effect for the 2021 season. Reminders: OVERNIGHT PERMITS Please be sure to have your overnight permits purchased and ready for the check in process. We will need to place them on the houseboat for you. If you have not purchased them visit http://recreation.gov. PET POLICY Ebel's is 100% pet friendly! We do have a $50.00 per pet charge for the stay and do have a 2 pet maximum per houseboat. You will need to pay this at check-in. EXTRA RENTALS A small boat is included with your houseboat, you may bring your own boat or your own motor for our small boat. You can also rent from us. YOU MUST HAVE A BOAT AND MOTOR IN TOW. PILLOWS/BLANKETS There are no pillows or blankets provided on ANY houseboat due to Covid-19 and Minnesota DNR restrictions.. Please bring your own. POLICIES: CPAP BATTERY RENTALS DISCOUNTIUED We are already experiencing difficulties with CPAP battery setups. Machines have changed and our setups are not able to handle new technology, therefore we are going to have to discontinue rental of battery packs and ask that you make arrangements with your health provider for battery use. -

Junior Ranger Activity Book Greetings Junior Ranger Voyageur Bingo

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Voyageurs National Park Junior Ranger Activity Book Greetings Junior Ranger Voyageur Bingo Welcome to Voyageurs National Park. This amazing place, covered There are many natural and man-made objects found in the park that help tell the park’s with forests and lakes, has been a National Park since 1975. story. These objects may be found indoors or outdoors. Park rangers work hard to protect the park and keep visitors safe. Bingo! Search for the items below as you travel through the park. Cross off (X) You can help by learning more about Voyageurs and taking a few each item as you find it. Try to get four in a row, diagonal, or the four corners. simple steps to keep the park healthy and beautiful. The compass rose is a tool that helps travelers find the direction they need to travel. Look for the compass rose on each page to find the directions for each activity. Bonjour! My name is Claude. Red Squirrel A HUGE Rock Park Ranger Spider Web To become a Junior Ranger, you will I am a French-Canadian need to: voyageur who paddled these lakes in the 1700s. I will be guiding Explore (check 2 or more) your journey through the park. Hike, ski, or snowshoe on a park trail Camp, fish, canoe, or enjoy another outdoor activity in the park Park Map Birch Bark Snowshoes Woodpecker Tree Attend a ranger-led program Watch the park film Learn (check 1 club and complete activities) Beaver Club: 5-6 activites (ages 6-8) Wolf Club: 7-8 activities (ages 8-10) Bald Eagle Arrowhead symbol North Canoe Island Bear Club: 9 or more activities (ages 10 and up) Protect Take the Junior Ranger pledge to protect Voyageurs Nationl Park White Pine Tree Wildlife Tracks Trail Sign Beaver Fur 2 3 A Voyageur Adventure Little American Island The word voyageur is French and means ‘traveller’. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Fujita Cabin Section Number 7 Page St

NFS Form 10-900 ———'——————————— f _____ 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Inter National Park Service National Register of Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for not applicable." F9r functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategpries from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Fujita, Jun Cabin other names/site number Sackett Cabin, Wendt Cabin 2. Location street & number Wendt Island, Voyageurs National Park (VOYA) CD not for publication city or town Ranier X vicinity state Minnesota code MN county St. Louis code 137 zip code 56668 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this Gu nomination LJ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property D meets D does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant LJ nationally LJ statewide Q locally. -

2021 Spring Newsletter

SPRING 2021 NORTHERN WAKE VOYAGEURS CONSERVANCY’S NEWSLETTER EXPLORE IT. SHARE IT. KEEP IT WILD. LEARN MORE AT VOYAGEURS.ORG Mandy Fuller The Voyageurs Conservancy is the official nonprofit partner of Minnesota’s Voyageurs National Park. In partnership with the National Park Service, the Conservancy works to preserve the wild character and unique experience of Voyageurs by funding projects and programs that will sustain it for generations to come. LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR The changing world around us has given us time to reflect on the work we do in partnership with the National Park Service and our member community. To reflect our expanding vision and commitment to the park, we underwent a major rebranding effort in 2020 to become the Voyageurs Conservancy. This change helps us grow our collective of park advocates. Now, more than ever, we must engage new voices, new Larry Sang Jr. visitors, and the next generation in the Debra Bernard SUMMER 2021 stewardship of our lands and waters to ensure a vibrant and sustainable National Park. LETTER FROM VOYAGEURS PARK PROGRAMS & FACILITIES 2021 PHOTO CONTEST CHECK OUT VOYAGEURS.ORG/EVENTS FOR THE This year brought unique challenges as NATIONAL PARK SUPERINTENDENT Voyageurs experienced monumental LATEST CONSERVANCY EVENTS & PROGRAMS The annual Voyageurs Photo Contest we navigated a global pandemic and, as We’ve heard it often over the last year, but assistance and cooperation, we achieved visitation numbers in 2020 and that trend opens in June! Submit your photos a result, unmatched visitation numbers. I will state it again... What an unprecedented Dark Sky Park certification in December 2020.