ARSC Journal, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Koymen-Mastersreport-2016

DISCLAIMER: This document does not meet current format guidelines Graduate School at the The University of Texas at Austin. of the It has been published for informational use only. Copyright by Erol Gregory Mehmet Koymen 2016 The Report Committee for Erol Gregory Mehmet Koymen Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Conservative Progressivism: Hasan Ferid Alnar and Symbolic Power in the Turkish Music Revolution APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Sonia Seeman, Supervisor Elliot Antokoletz Conservative Progressivism: Hasan Ferid Alnar and Symbolic Power in the Turkish Music Revolution by Erol Gregory Mehmet Koymen, B.M. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music The University of Texas at Austin May 2016 Acknowledgements. Many people and organizations have made this master’s report possible. For their generous financial support, I would like to thank the following organizations: the Butler School of Music, which has provided both a Butler Excellence Scholarship and a teaching assistantship; The University of Texas at Austin Center for Middle Eastern Studies, for a Summer 2014 FLAS grant to study Turkish; The University of Texas at Austin Center for European Studies, for an Academic Year 2014-2015 FLAS grant to study Turkish; the Butler School of Music, the University of Texas at Austin Graduate School, and the University of Texas at Austin Center for Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies, for professional development grants; the Institute of Turkish Studies, for a Summer Language Grant; and the American Research Insitute in Turkey, for a Summer Fellowship for Intensive Advanced Turkish Language Study at Boğaziçi University. -

Die Münchner Philharmoniker

Die Münchner Philharmoniker Die Münchner Philharmoniker wurden 1893 auf Privatinitiative von Franz Kaim, Sohn eines Klavierfabrikanten, gegründet und prägen seither das musikalische Leben Münchens. Bereits in den Anfangsjahren des Orchesters – zunächst unter dem Namen »Kaim-Orchester« – garantierten Dirigenten wie Hans Winderstein, Hermann Zumpe und der Bruckner-Schüler Ferdinand Löwe hohes spieltechnisches Niveau und setzten sich intensiv auch für das zeitgenössische Schaffen ein. Von Anbeginn an gehörte zum künstlerischen Konzept auch das Bestreben, durch Programm- und Preisgestaltung allen Bevölkerungs-schichten Zugang zu den Konzerten zu ermöglichen. Mit Felix Weingartner, der das Orchester von 1898 bis 1905 leitete, mehrte sich durch zahlreiche Auslandsreisen auch das internationale Ansehen. Gustav Mahler dirigierte das Orchester in den Jahren 1901 und 1910 bei den Uraufführungen seiner 4. und 8. Symphonie. Im November 1911 gelangte mit dem inzwischen in »Konzertvereins-Orchester« umbenannten Ensemble unter Bruno Walters Leitung Mahlers »Das Lied von der Erde« zur Uraufführung. Von 1908 bis 1914 übernahm Ferdinand Löwe das Orchester erneut. In Anknüpfung an das triumphale Wiener Gastspiel am 1. März 1898 mit Anton Bruckners 5. Symphonie leitete er die ersten großen Bruckner- Konzerte und begründete so die bis heute andauernde Bruckner-Tradition des Orchesters. In die Amtszeit von Siegmund von Hausegger, der dem Orchester von 1920 bis 1938 als Generalmusikdirektor vorstand, fielen u.a. die Uraufführungen zweier Symphonien Bruckners in ihren Originalfassungen sowie die Umbenennung in »Münchner Philharmoniker«. Von 1938 bis zum Sommer 1944 stand der österreichische Dirigent Oswald Kabasta an der Spitze des Orchesters. Eugen Jochum dirigierte das erste Konzert nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. Mit Hans Rosbaud gewannen die Philharmoniker im Herbst 1945 einen herausragenden Orchesterleiter, der sich zudem leidenschaftlich für neue Musik einsetzte. -

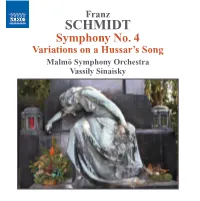

Franz Schmidt

Franz Schmidt (1874 – 1939) was born in Pressburg, now Bratislava, a citizen of the Austro- Hungarian Empire and died in Vienna, a citizen of the Nazi Reich by virtue of Hitler's Anschluss which had then recently annexed Austria into the gathering darkness closing over Europe. Schmidt's father was of mixed Austrian-Hungarian background; his mother entirely Hungarian; his upbringing and schooling thoroughly in the prevailing German-Austrian culture of the day. In 1888 the Schmidt family moved to Vienna, where Franz enrolled in the Conservatory to study composition with Robert Fuchs, cello with Ferdinand Hellmesberger and music theory with Anton Bruckner. He graduated "with excellence" in 1896, the year of Bruckner's death. His career blossomed as a teacher of cello, piano and composition at the Conservatory, later renamed the Imperial Academy. As a composer, Schmidt may be seen as one of the last of the major musical figures in the long line of Austro-German composers, from Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler. His four symphonies and his final, great masterwork, the oratorio Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln (The Book with Seven Seals) are rightly seen as the summation of his creative work and a "crown jewel" of the Viennese symphonic tradition. Das Buch occupied Schmidt during the last years of his life, from 1935 to 1937, a time during which he also suffered from cancer – the disease that would eventually take his life. In it he sets selected passages from the last book of the New Testament, the Book of Revelation, tied together with an original narrative text. -

570034Bk Hasse 23/8/10 5:34 PM Page 4

572118bk Schmidt4:570034bk Hasse 23/8/10 5:34 PM Page 4 Vassily Sinaisky Vassily Sinaisky’s international career was launched in 1973 when he won the Gold Franz Medal at the prestigious Karajan Competition in Berlin. His early work as Assistant to the legendary Kondrashin at the Moscow Philharmonic, and his study with Ilya Musin at the Leningrad Conservatory provided him with an incomparable grounding. SCHMIDT He has been professor in conducting at the Music Conservatory in St Petersburg for the past thirty years. Sinaisky was Music Director and Principal Conductor of the Photo: Jesper Lindgren Moscow Philharmonic from 1991 to 1996. He has also held the posts of Chief Symphony No. 4 Conductor of the Latvian Symphony and Principal Guest Conductor of the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra. He was appointed Music Director and Principal Variations on a Hussar’s Song Conductor of the Russian State Orchestra (formerly Svetlanov’s USSR State Symphony Orchestra), a position which he held until 2002. He is Chief Guest Conductor of the BBC Philharmonic and is a regular and popular visitor to the BBC Malmö Symphony Orchestra Proms each summer. In January 2007 Sinaisky took over as Principal Conductor of the Malmö Symphony Orchestra in Sweden. His appointment forms part of an ambitious new development plan for Vassily Sinaisky the orchestra which has already resulted in hugely successful projects both in Sweden and further afield. In September 2009 he was appointed a ‘permanent conductor’ at the Bolshoi in Moscow (a position shared with four other conductors). Malmö Symphony Orchestra The Malmö Symphony Orchestra (MSO) consists of a hundred highly talented musicians who demonstrate their skills in a wide range of concerts. -

Recording Master List.Xls

UPDATED 11/20/2019 ENSEMBLE CONDUCTOR YEAR Bartok - Concerto for Orchestra Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop 2009 Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra Rafael Kubelik 1978L BBC National Orchestra of Wales Tadaaki Otaka 2005L Berlin Philharmonic Herbert von Karajan 1965 Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra Ferenc Fricsay 1957 Boston Symphony Orchestra Erich Leinsdorf 1962 Boston Symphony Orchestra Rafael Kubelik 1973 Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa 1995 Boston Symphony Orchestra Serge Koussevitzky 1944 Brussels Belgian Radio & TV Philharmonic OrchestraAlexander Rahbari 1990 Budapest Festival Orchestra Iván Fischer 1996 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Fritz Reiner 1955 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Georg Solti 1981 Chicago Symphony Orchestra James Levine 1991 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Pierre Boulez 1993 Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra Paavo Jarvi 2005 City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Simon Rattle 1994L Cleveland Orchestra Christoph von Dohnányi 1988 Cleveland Orchestra George Szell 1965 Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam Antal Dorati 1983 Detroit Symphony Orchestra Antal Dorati 1983 Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra Tibor Ferenc 1992 Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra Zoltan Kocsis 2004 London Symphony Orchestra Antal Dorati 1962 London Symphony Orchestra Georg Solti 1965 London Symphony Orchestra Gustavo Dudamel 2007 Los Angeles Philharmonic Andre Previn 1988 Los Angeles Philharmonic Esa-Pekka Salonen 1996 Montreal Symphony Orchestra Charles Dutoit 1987 New York Philharmonic Leonard Bernstein 1959 New York Philharmonic Pierre -

Cultural Death Music Under Tyranny Kabasta • Hoehn • Fried

Cultural Death Music under Tyranny Kabasta • Hoehn • Fried Cultural Death: Music under Tyranny Oswald Kabasta • Alfred Hoehn • Oskar Fried Lost artifacts by three musicians have resurfaced out of Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union, each of whom arrived at a horrid end. The Nazis had implemented a program 1. Beethoven: Leonore Overture, no. 2 13'10" of bringing forcible-coordination to all their ideas and goals, known as gleichschaltung, an Oswald Kabasta conducting the Munich Philharmonic electrical term that involves the “switching” of elements to be compatible within a circuit, or rec. c. 1942-44. unissued 2RA 5690/3 previously unpublished power system: this concept is an apt description of Nazification. It fueled Kabasta's success whereas Hoehn and Fried were unadaptable outsiders whose artistic and personal integrity 2. Brahms: Piano Concerto no. 2, Op. 86: I. Allegro non troppo 15"39" remain with us, living on in the deep spirituality evident in their recorded performances. Alfred Hoehn, piano; Reinhold Merten conducting the Leipzig Radio Orchestra The Nazis’ broad rise on the cultural front began in 1920 when they relaunched the rec. 1940.4.5. licensed from RBB Media previously unpublished failed Völkischer Beobachter newspaper. A respectable pseudo-intellectual facade lured the German public into accepting an ideology that viewed the past through a pathologically Berlioz: Symphony fantastique 50'10" distorted lens, while imposing their National Socialist revisionism onto a millennial chain 3. I. Rêveries – Passions. 14'26" of disparate historic events and personages. Their articles progressively manipulated every 4. II. Un bal. Valse. 6'55' well-known protagonist, past or present, German or otherwise. -

C K’NAY C (To Her) C (Poem by A

K ney C k’NAY C (To Her) C (poem by A. Belïy [(A.) BAY-lee] set to music by Sergei Rachmaninoff [sehr-GAYEE rahk-MAH-nyih-nuff]) Kaan C JindÍich z Albestç Kàan C YINND-rshihk z’AHL-bess-too KAHAHN C (known also as Heinrich Kàan-Albest [H¦N-rihh KAHAHN-AHL-besst]) Kabaivanska C Raina Kabaivanska C rah-EE-nah kah-bahih-WAHN-skuh C (known also as Raina Yakimova [yah-KEE-muh-vuh] Kabaivanska) Kabalevsky C Dmitri Kabalevsky C d’MEE-tree kah-bah-LYEFF-skee C (known also as Dmitri Borisovich Kabalevsky [d’MEE-tree bah-REE-suh-vihch kah-bah-LYEFF-skee]) C (the first name is also transliterated as Dmitry) Kabasta C Oswald Kabasta C AWSS-vahlt kah-BAHSS-tah Kabelac C Miloslav Kabelá C MIH-law-slahf KAH-beh-lahahsh Kabos C Ilona Kabós C IH-law-nuh KAH-bohohsh Kacinskas C Jerome Ka inskas C juh-ROHM kah-CHINN-skuss C (known also as Jeronimas Ka inskas [yeh-raw-NEE-mahss kah-CHEEN-skahss]) Kaddish for terezin C Kaddish for Terezin C kahd-DIHSH (for) TEH-reh-zinn C (a Holocaust Requiem [{REH-kôôee-umm} REH-kôôih-emm] by Ronald Senator [RAH-nulld SEH-nuh-tur]) C (Kaddish is a Jewish mourner’s prayer, and Terezin is a Czechoslovakian town converted to a concentration camp by the Nazis during World War II, where more than 15,000 Jewish children perished) Kade C Otto Kade C AWT-toh KAH-duh Kadesh urchatz C Kadesh Ur'chatz C kah-DEHSH o-HAHTSS C (Bless and Wash — a prayer song) Kadosa C Pál Kadosa C PAHAHL KAH-daw-shah Kadosh sanctus C Kadosh, Sanctus C kah-DAWSH, SAHNGK-tawss C (section of the Holocaust Reqiem — Kaddish for Terezin [kahd-DIHSH (for) TEH-reh-zinn] -

Romantic Piano Concerto

Joseph MARX Romantic Piano Concerto Castelli Romani David Lively, Piano Bochum Symphony Orchestra • Steven Sloane Joseph Marx (1882–1964) Piano Concertos Lying beneath the piano while one’s mother practises spectacular choral works with orchestral accompaniment, Marx and his ‘house pianist’ Angelo Kessissoglu, a The first movement, Lebhaft (Allegro moderato) , concert pieces and gazing at sheets of music without inlcluding Herbstchor an Pan (‘Autumn Chorus to Pan’), native of Trieste, gave the first performance of the follows sonata form. It opens with a measured drum roll understanding them might not always seem the ideal Morgengesang (‘Morning Song’), Abendweise (‘Evening Romantisches Klavierkonzert in the summer of 1919 in introducing the passionate initial theme. Next comes a prerequisite for subsequently becoming a composer, Melody’) and Ein Neujahrshymnus (‘A New Year’s Hymn’ the version for two pianos (remarkably, Kessissoglu was songlike theme played on the winds, that proceeds music teacher and critic of some renown. In the case of – this latter work was orchestrated later on, but since the still playing and accompanying works by Marx in the early through several episodes of increasing intensity. The Joseph Marx (1882–1964), however, this did indeed orchestral score has been lost, a new arrangement was 1980s!). Once Marx had orchestrated the work, the development, in 6/8 rhythm, recalls the main theme, albeit prove to be the case. Marx’s mother noticed her son’s made in 2004). After going on to write a considerable premiere of -

Kaim-Chor) 30.12.96 Te Deum Meta Hieber (S), Elisabeth Exter (A), U

Munich Philharmonic Bruckner Concerts (1896 – 1954) Between 1896 and 1902 Te Deum (Kaim-Chor) 30.12.96 Te Deum Meta Hieber (s), Elisabeth Exter (a), U. Schreiber (t), Eduard Schuegraf (bs), Kaim- Chor, Herman Zumpe (Kaim-Saal, 19:00 Uhr, Bruckner Gedaechtnis-Konzert) 13.01.97 B4 Herman Zumpe (4. Symphoniekonzert, Kaim-Saal, 19:00 Uhr, Bruckner Gedaechtnis- Konzert) 20.01.97 B4 Herman Zumpe (5. Symphoniekonzert, Kaim-Saal, 19:30 Uhr, Bruckner Gedaechtnis- Konzert) 04.02.98 B5 Ferdinand Loewe (3. Symphoniekonzert, Kaim-Saal, Deutsche Erstauffuehrung) 01.03.98 B5 Ferdinand Loewe (Wiener Erstauffuehrung, Musikverein, Grosses Saal, 20 Uhr) 10.02.99 B7 Siegmund von Hausegger 17.12.00 B8 Siegmund von Hausegger (Muncher Erstauffuehrung) 13.11.03 B9 Bernhard Stavenhagen (Munchener Erstauffuehrung, Erster moderner Abend) 20.02.05 ? B4, B9 Ferdinand Loewe (Erstes Munchner Anton-Bruckner-Fest, Erstes Abend) 21.02.05 B6, 150. Psalm Ferdinand Loewe (Muenchner Erstauffuehrung, Erstes Muenchner Anton- Bruckner-Fest, Zweites Abend) 19.02.06 B9 Wilhelm Furtwaengler 03.10.07 B5 Alfred Westarp (alias of Egon Victor Frensdorff) Tonhalle (previously called Kaim-Saal) 08.-09.09 Beethoven-Brahms-Bruckner-Zyklus 17.10.10 B1 Ferdinand Loewe 14.11.10 B2 Ferdinand Loewe 21.11.10 B3 Ferdinand Loewe (Fassung 1890) 09.01.11 B4 Ferdinand Loewe (Fassung 1889) 30.01.11 B5 Ferdinand Loewe 13.02.11 B6 Ferdinand Loewe 27.02.11 B7 Ferdinand Loewe 06.03.11 B8, 150. Psalm Ferdinand Loewe (Charles Cahier) 10.04.11 B9, Te Deum Ferdinand Loewe 22.01.19 B4 Wilhelm Furtwaengler (6. Ab.-Kz.) 21.01.20 B5 Hans Pfitzner 20.10.20 B7 Siegmund von Hausegger 03.01.21 B9 Werner von Buelow 10.11.21 B00 Andante Frederick Charles Adler (Muenchner Erstauffuehrung. -

Orchesterbiografie Wiener Symphoniker Chefdirigent: Philippe

Orchesterbiografie Wiener Symphoniker Chefdirigent: Philippe Jordan Ehrendirigenten: Georges Prêtre, Wolfgang Sawallisch † Die Wiener Symphoniker sind Wiens Konzertorchester und Kulturbotschafter und damit verantwortlich für den weitaus größten Teil des symphonischen Musiklebens dieser Stadt. Innovative Projekte in Verbindung mit einer bewussten Pflege der traditionellen Wiener Klangkultur nehmen einen zentralen Stellenwert in den Aktivitäten des Orchesters ein. Im Oktober 1900 präsentierte sich der neue Klangkörper (damals unter dem Namen „Wiener Concertverein“) mit Ferdinand Löwe am Pult im Großen Musikvereinssaal erstmals der Öffentlichkeit. Heute so selbstverständlich im Repertoire verankerte Werke wie Anton Bruckners Neunte Symphonie, Arnold Schönbergs Gurre-Lieder, Maurice Ravels Konzert für die linke Hand und Franz Schmidts Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln wurden von den Wiener Symphonikern uraufgeführt. Im Laufe seiner Geschichte prägten herausragende Dirigentenpersönlichkeiten wie Bruno Walter, Richard Strauss, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Oswald Kabasta, George Szell oder Hans Knappertsbusch entscheidend den Klangkörper. In den letzten Jahrzehnten waren es die Chefdirigenten Herbert von Karajan (1950–1960) und Wolfgang Sawallisch (1960 –1970), die das Klangbild des Orchesters formten. In dieser Position folgten – nach kurzzeitiger Rückkehr von Josef Krips – Carlo Maria Giulini und Gennadij Roshdestvenskij. Georges Prêtre war zwischen 1986 und 1991 Chefdirigent, danach übernahmen Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos, Vladimir Fedosejev und zuletzt Fabio -

Franz Schmidt (Geb

Franz Schmidt (geb. Bratislava (Preßburg), 22. Dezember 1874 — gest. Perchtoldsdorf, 11. Februar 1939) IV. Symphonie C-Dur (1932-33) Allegro molto moderato (p. 1) – Adagio (p. 39) – Più lento (p. 44) – Poco a poco Tempo di Adagio, p. 56) Molto vivace (p. 63) – Tempo I (Allegro molto moderato), un poco sostenuto (p. 118) Vorwort Franz Schmidt wird von seinen Anhängern als bedeutendster Fortführer der aus der Romantik geborenen großen österreichischen symphonischen Tradition nach Anton Bruckner und Gustav Mahler verstanden. Die unmittelbare Wirkung dieser beiden Meister auf das Publikum ist ihm versagt geblieben, und heute wird man seinen Namen eher neben denjenigen etwa seiner Zeitgenossen Hans Pfitzner, Hermann Hans Wetzler, Max Reger, Siegmund von Hausegger oder Karl Weigl nennen. Schmidts üppiger, zum Überladenen neigender Stil ist unverkennbar persönlich, und in der kontrapunktischen Kunst und harmonischen Komplexität steht er ganz auf der Höhe seiner Zeit. Unter Franz Schmidts vier Symphonien ist die hier vorliegende Zweite die komplizierteste und auch die größte Herausforderung für die Orchestermusiker. Franz Schmidt war zunächst Klavierstudent bei Theodor Leschetizky (1830-1915), dem einstigen Schüler von Carl Czerny und Simon Sechter und Lehrmeister unzähliger Meisterpianisten wie Ignaz Paderewski, Artur Schnabel, Ignace Tiegerman, Ignaz Friedman, Mieczyslaw Horszowski, Benno Moiseiwitsch, Ossip Gabrilowitsch, Mark Hambourg, Severin Eisenberger oder Paul Wittgenstein. Doch verließ er seinen Lehrmeister im Dissens, und studierte von 1888 bis 1896 am Konservatorium der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien Komposition bei Robert Fuchs (1847-1927) und Violoncello bei Ferdinand Hellmesberger (1863-1940). 1896-1911 war Schmidt Cellist der Wiener Philharmoniker und anschließend bis 1914 Solocellist des Hofopernorchesters (heute Orchester der Wiener Staatsoper). -

Mahler Strauss

Mahler KINDERTOTENLIEDER BRIGITTE FASSBAENDER Strauss TOD UND VERKLÄRUNG SERGIU CELIBIDACHE Throughout his life Sergiu Celibidache refused to allow recordings of his concerts to be released on CD. In spite of this his family has now decided to release a number of selected and particularly valuable archival recordings as a precious memento of a great conductor and of his unique work with the Munich Philharmonic. --------------- Sergiu Celibidache lehnte es zeitlebens ab, Mitschnitte seiner Konzerte auf CD zu veröffentlichen. Seine Familie hat sich nun trotzdem entschieden, einige ausgewählte und besonders wertvolle Archiv-Aufnahmen als kostbare Erinnerungen an einen großen Dirigenten und die einzigartige Zusammenarbeit mit den Münchner Philharmonikern zur Veröffentlichung freizugeben. Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) Kindertotenlieder Songs on the Death of Children Text: Friedrich Rückert 1 1. Nun will die Sonn’ so hell aufgehn 7:42 2 2. Nun seh ich wohl, warum so dunkle Flammen 5:39 3 3. Wenn dein Mütterlein 5:45 4 4. Oft denk ich, sie sind nur ausgegangen 2:56 5 5. In diesem Wetter, in diesem Braus 7:13 6 Applause · Applaus 0:43 Richard Strauss (1864–1949) 7 Tod und Verklärung op. 24 30:11 Death and Transfiguration 8 Applause · Applaus 0:38 BRIGITTE FASSBAENDER mezzo-soprano MÜNCHNER PHILHARMONIKER SERGIU CELIBIDACHE Endangered idyll Recalling the genesis of the Kindertotenlieder press the poet’s grief following the death of his that her husband wrote in Maiernigg on the two youngest children from scarlet fever. Wörther See during the summer months of 1901 Writers on Mahler continue to puzzle over and 1904, Alma Mahler expressed her incredu- Mahler’s reasons for setting these poems.