Philippe Jordan WIENER SYMPHONIKER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES Composers

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KHAIRULLO ABDULAYEV (b. 1930, TAJIKISTAN) Born in Kulyab, Tajikistan. He studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory under Anatol Alexandrov. He has composed orchestral, choral, vocal and instrumental works. Sinfonietta in E minor (1964) Veronica Dudarova/Moscow State Symphony Orchestra ( + Poem to Lenin and Khamdamov: Day on a Collective Farm) MELODIYA S10-16331-2 (LP) (1981) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where he studied under Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. His other Symphonies are Nos. 1 (1962), 3 in B flat minor (1967) and 4 (1969). Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1964) Valentin Katayev/Byelorussian State Symphony Orchestra ( + Vagner: Suite for Symphony Orchestra) MELODIYA D 024909-10 (LP) (1969) VASIF ADIGEZALOV (1935-2006, AZERBAIJAN) Born in Baku, Azerbaijan. He studied under Kara Karayev at the Azerbaijan Conservatory and then joined the staff of that school. His compositional catalgue covers the entire range of genres from opera to film music and works for folk instruments. Among his orchestral works are 4 Symphonies of which the unrecorded ones are Nos. 1 (1958) and 4 "Segah" (1998). Symphony No. 2 (1968) Boris Khaikin/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1968) ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, Poem Exaltation for 2 Pianos and Orchestra, Africa Amidst MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Symphonies A-G Struggles, Garabagh Shikastasi Oratorio and Land of Fire Oratorio) AZERBAIJAN INTERNATIONAL (3 CDs) (2007) Symphony No. -

Koymen-Mastersreport-2016

DISCLAIMER: This document does not meet current format guidelines Graduate School at the The University of Texas at Austin. of the It has been published for informational use only. Copyright by Erol Gregory Mehmet Koymen 2016 The Report Committee for Erol Gregory Mehmet Koymen Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Conservative Progressivism: Hasan Ferid Alnar and Symbolic Power in the Turkish Music Revolution APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Sonia Seeman, Supervisor Elliot Antokoletz Conservative Progressivism: Hasan Ferid Alnar and Symbolic Power in the Turkish Music Revolution by Erol Gregory Mehmet Koymen, B.M. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music The University of Texas at Austin May 2016 Acknowledgements. Many people and organizations have made this master’s report possible. For their generous financial support, I would like to thank the following organizations: the Butler School of Music, which has provided both a Butler Excellence Scholarship and a teaching assistantship; The University of Texas at Austin Center for Middle Eastern Studies, for a Summer 2014 FLAS grant to study Turkish; The University of Texas at Austin Center for European Studies, for an Academic Year 2014-2015 FLAS grant to study Turkish; the Butler School of Music, the University of Texas at Austin Graduate School, and the University of Texas at Austin Center for Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies, for professional development grants; the Institute of Turkish Studies, for a Summer Language Grant; and the American Research Insitute in Turkey, for a Summer Fellowship for Intensive Advanced Turkish Language Study at Boğaziçi University. -

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club Since you’re reading this booklet, you’re obviously someone who likes to explore music more widely than the mainstream offerings of most other labels allow. Toccata Classics was set up explicitly to release recordings of music – from the Renaissance to the present day – that the microphones have been ignoring. How often have you heard a piece of music you didn’t know and wondered why it hadn’t been recorded before? Well, Toccata Classics aims to bring this kind of neglected treasure to the public waiting for the chance to hear it – from the major musical centres and from less-well-known cultures in northern and eastern Europe, from all the Americas, and from further afield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, Toccata Classics is exploring it. To link label and listener directly we run the Toccata Discovery Club, which brings its members substantial discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings, whether CDs or downloads, and also on the range of pioneering books on music published by its sister company, Toccata Press. A modest annual membership fee brings you, free on joining, two CDs, a Toccata Press book or a number of album downloads (so you are saving from the start) and opens up the entire Toccata Classics catalogue to you, both new recordings and existing releases as CDs or downloads, as you prefer. Frequent special offers bring further discounts. If you are interested in joining, please visit the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com and click on the ‘Discovery Club’ tab for more details. -

Michael Volle Baritone

Michael Volle Baritone Michael Volle has established himself as Michael Volle dedicates also a great part of one of the leading baritones, receiving the his career to lied recitals and to concert important German Theatre Award "Faust" commitments with the world's finest and awarded "Singer of the Year" by the orchestras and with important conductors opera magazine "Opernwelt". He studied such as Daniel Barenboim, Zubin Mehta, with Josef Metternich and Rudolf Piernay. Maurizio Pollini, Seiji Ozawa, Charles Dutoit, Riccardo Muti, Franz Welser-Möst, Antonio His first permanent engagements were at Pappano, Philippe Jordan, Valerij Gergiev, Mannheim, Bonn, Düsseldorf and Cologne. Kent Nagano, Wolfgang Sawallisch, Mariss From 1999 until 2007 Michael Volle was a Jansons, Thomas Hengelbrock, Philippe member of the ensemble of the Zurich Opera Herreweghe, James Conlon, James Levine. House where he sang various roles in new productions, including Beckmesser Die Alongside TV appearances on ARTE, Michael Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Eugene Volle has recorded CD and DVD releases for Onegin , Golaud Pelléas et Mélisande, the EMI, Harmonia Mundi, Arthaus, Naxos Marcello La Bohème, Count Le Nozze di and Philipps labels, including a film Figaro and Barak Die Frau ohne Schatten production of Der Freischütz in 2009. (2009), Wolfram Tannhäuser (2011) and Michael Volle is recipient of the important Hans Sachs Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg German Theatre Award "Faust" and "Singer (2012). of the Year" by the opera magazine "Opernwelt" (in 2008 and 2014). Since -

Die Münchner Philharmoniker

Die Münchner Philharmoniker Die Münchner Philharmoniker wurden 1893 auf Privatinitiative von Franz Kaim, Sohn eines Klavierfabrikanten, gegründet und prägen seither das musikalische Leben Münchens. Bereits in den Anfangsjahren des Orchesters – zunächst unter dem Namen »Kaim-Orchester« – garantierten Dirigenten wie Hans Winderstein, Hermann Zumpe und der Bruckner-Schüler Ferdinand Löwe hohes spieltechnisches Niveau und setzten sich intensiv auch für das zeitgenössische Schaffen ein. Von Anbeginn an gehörte zum künstlerischen Konzept auch das Bestreben, durch Programm- und Preisgestaltung allen Bevölkerungs-schichten Zugang zu den Konzerten zu ermöglichen. Mit Felix Weingartner, der das Orchester von 1898 bis 1905 leitete, mehrte sich durch zahlreiche Auslandsreisen auch das internationale Ansehen. Gustav Mahler dirigierte das Orchester in den Jahren 1901 und 1910 bei den Uraufführungen seiner 4. und 8. Symphonie. Im November 1911 gelangte mit dem inzwischen in »Konzertvereins-Orchester« umbenannten Ensemble unter Bruno Walters Leitung Mahlers »Das Lied von der Erde« zur Uraufführung. Von 1908 bis 1914 übernahm Ferdinand Löwe das Orchester erneut. In Anknüpfung an das triumphale Wiener Gastspiel am 1. März 1898 mit Anton Bruckners 5. Symphonie leitete er die ersten großen Bruckner- Konzerte und begründete so die bis heute andauernde Bruckner-Tradition des Orchesters. In die Amtszeit von Siegmund von Hausegger, der dem Orchester von 1920 bis 1938 als Generalmusikdirektor vorstand, fielen u.a. die Uraufführungen zweier Symphonien Bruckners in ihren Originalfassungen sowie die Umbenennung in »Münchner Philharmoniker«. Von 1938 bis zum Sommer 1944 stand der österreichische Dirigent Oswald Kabasta an der Spitze des Orchesters. Eugen Jochum dirigierte das erste Konzert nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. Mit Hans Rosbaud gewannen die Philharmoniker im Herbst 1945 einen herausragenden Orchesterleiter, der sich zudem leidenschaftlich für neue Musik einsetzte. -

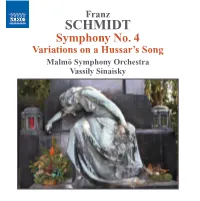

Franz Schmidt

Franz Schmidt (1874 – 1939) was born in Pressburg, now Bratislava, a citizen of the Austro- Hungarian Empire and died in Vienna, a citizen of the Nazi Reich by virtue of Hitler's Anschluss which had then recently annexed Austria into the gathering darkness closing over Europe. Schmidt's father was of mixed Austrian-Hungarian background; his mother entirely Hungarian; his upbringing and schooling thoroughly in the prevailing German-Austrian culture of the day. In 1888 the Schmidt family moved to Vienna, where Franz enrolled in the Conservatory to study composition with Robert Fuchs, cello with Ferdinand Hellmesberger and music theory with Anton Bruckner. He graduated "with excellence" in 1896, the year of Bruckner's death. His career blossomed as a teacher of cello, piano and composition at the Conservatory, later renamed the Imperial Academy. As a composer, Schmidt may be seen as one of the last of the major musical figures in the long line of Austro-German composers, from Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler. His four symphonies and his final, great masterwork, the oratorio Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln (The Book with Seven Seals) are rightly seen as the summation of his creative work and a "crown jewel" of the Viennese symphonic tradition. Das Buch occupied Schmidt during the last years of his life, from 1935 to 1937, a time during which he also suffered from cancer – the disease that would eventually take his life. In it he sets selected passages from the last book of the New Testament, the Book of Revelation, tied together with an original narrative text. -

570034Bk Hasse 23/8/10 5:34 PM Page 4

572118bk Schmidt4:570034bk Hasse 23/8/10 5:34 PM Page 4 Vassily Sinaisky Vassily Sinaisky’s international career was launched in 1973 when he won the Gold Franz Medal at the prestigious Karajan Competition in Berlin. His early work as Assistant to the legendary Kondrashin at the Moscow Philharmonic, and his study with Ilya Musin at the Leningrad Conservatory provided him with an incomparable grounding. SCHMIDT He has been professor in conducting at the Music Conservatory in St Petersburg for the past thirty years. Sinaisky was Music Director and Principal Conductor of the Photo: Jesper Lindgren Moscow Philharmonic from 1991 to 1996. He has also held the posts of Chief Symphony No. 4 Conductor of the Latvian Symphony and Principal Guest Conductor of the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra. He was appointed Music Director and Principal Variations on a Hussar’s Song Conductor of the Russian State Orchestra (formerly Svetlanov’s USSR State Symphony Orchestra), a position which he held until 2002. He is Chief Guest Conductor of the BBC Philharmonic and is a regular and popular visitor to the BBC Malmö Symphony Orchestra Proms each summer. In January 2007 Sinaisky took over as Principal Conductor of the Malmö Symphony Orchestra in Sweden. His appointment forms part of an ambitious new development plan for Vassily Sinaisky the orchestra which has already resulted in hugely successful projects both in Sweden and further afield. In September 2009 he was appointed a ‘permanent conductor’ at the Bolshoi in Moscow (a position shared with four other conductors). Malmö Symphony Orchestra The Malmö Symphony Orchestra (MSO) consists of a hundred highly talented musicians who demonstrate their skills in a wide range of concerts. -

Digital Concert Hall

Digital Concert Hall Streaming Partner of the Digital Concert Hall 21/22 season Where we play just for you Welcome to the Digital Concert Hall The Berliner Philharmoniker and chief The coming season also promises reward- conductor Kirill Petrenko welcome you to ing discoveries, including music by unjustly the 2021/22 season! Full of anticipation at forgotten composers from the first third the prospect of intensive musical encoun- of the 20th century. Rued Langgaard and ters with esteemed guests and fascinat- Leone Sinigaglia belong to the “Lost ing discoveries – but especially with you. Generation” that forms a connecting link Austro-German music from the Classi- between late Romanticism and the music cal period to late Romanticism is one facet that followed the Second World War. of Kirill Petrenko’s artistic collaboration In addition to rediscoveries, the with the orchestra. He continues this pro- season offers encounters with the latest grammatic course with works by Mozart, contemporary music. World premieres by Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Olga Neuwirth and Erkki-Sven Tüür reflect Brahms and Strauss. Long-time compan- our diverse musical environment. Artist ions like Herbert Blomstedt, Sir John Eliot in Residence Patricia Kopatchinskaja is Gardiner, Janine Jansen and Sir András also one of the most exciting artists of our Schiff also devote themselves to this core time. The violinist has the ability to capti- repertoire. Semyon Bychkov, Zubin Mehta vate her audiences, even in challenging and Gustavo Dudamel will each conduct works, with enthusiastic playing, technical a Mahler symphony, and Philippe Jordan brilliance and insatiable curiosity. returns to the Berliner Philharmoniker Numerous debuts will arouse your after a long absence. -

04-30-2019 Walkure Eve.Indd

RICHARD WAGNER der ring des nibelungen conductor Die Walküre Philippe Jordan Opera in three acts production Robert Lepage Libretto by the composer associate director Tuesday, April 30, 2019 Neilson Vignola 6:00–11:00 PM set designer Carl Fillion costume designer François St-Aubin lighting designer Etienne Boucher The production of Die Walküre was made video image artist possible by a generous gift from Ann Ziff and Boris Firquet the Ziff Family, in memory of William Ziff revival stage directors The revival of this production is made possible Gina Lapinski J. Knighten Smit by a gift from Ann Ziff general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin In collaboration with Ex Machina 2018–19 SEASON The 541st Metropolitan Opera performance of RICHARD WAGNER’S die walküre conductor Philippe Jordan in order of vocal appearance siegmund waltr aute Stuart Skelton Renée Tatum* sieglinde schwertleite Eva-Maria Westbroek Daryl Freedman hunding ortlinde Günther Groissböck Wendy Bryn Harmer* wotan siegrune Michael Volle Eve Gigliotti brünnhilde grimgerde Christine Goerke* Maya Lahyani frick a rossweisse Jamie Barton Mary Phillips gerhilde Kelly Cae Hogan helmwige Jessica Faselt** Tuesday, April 30, 2019, 6:00–11:00PM Musical Preparation Carol Isaac, Jonathan C. Kelly, Dimitri Dover*, and Marius Stieghorst Assistant Stage Directors Stephen Pickover and Paula Suozzi Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter German Coach Marianne Barrett Prompter Carol Isaac Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted -

Bruckner Symphony Cycles (Not Commercially Available As Recordings) Compiled by John F

Bruckner Symphony Cycles (not commercially available as recordings) Compiled by John F. Berky – June 3, 2020 (Updated May 20, 2021) 1910 /11 – Ferdinand Löwe – Wiener Konzertverein Orchester 1] 25.10.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 1] 24.01.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (Graz) 2] 02.11.10 - Martin Spoerr 2] 20.11.10 - Martin Spoerr 2] 29.04.11 - Martin Spoerr (Bamberg) 3] 25.11.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 3] 26.11.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 3] 08.01.11 - Gustav Gutheil 3] 26.01.11- Ferdinand Loewe (Zagreb) 3] 17.04.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (Budapest) 4] 07.01.11 - Hans Maria Wallner 4] 12.02.11 - Martin Spoerr 4] 18.02.11 - Hans Maria Wellner 4] 26.02.11 - Hans Maria Wallner 4] 02.03.11 - Hans Maria Wallner 4] 23.04.11 - Franz Schalk 5] 05.02.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 6] 21.02.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 7] 03.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 7] 17.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 7] 02.04.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 8] 23.02.11 - Oskar Nedbal 8] 12.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 9] 24.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 1910/11 – Ferdinand Löwe – Munich Philharmonic 1] 17.10.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 2] 14.11.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 3] 21.11.10 - Ferdinand Loewe (Fassung 1890) 4] 09.01.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (Fassung 1889) 5] 30.01.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 6] 13.02.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 7] 27.02.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 8] 06.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (with Psalm 150 -Charles Cahier) 9] 10.04.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (with Te Deum) 1919/20 – Arthur Nikisch – Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra 1] 09.10.19 - Artur Nikisch (1. -

TOCC0327DIGIBKLT.Pdf

VISSARION SHEBALIN: COMPLETE MUSIC FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO by Paul Conway Vissarion Shebalin was one of the foremost composers and teachers in the Soviet Union. Dmitri Shostakovich held him in the highest esteem; he kept a portrait of his slightly older friend and colleague hanging on his wall and wrote this heartfelt obituary: Shebalin was an outstanding man. His kindness, honesty and absolute adherence to principle always amazed me. His enormous talent and great mastery immediately earned him burning love and authority with friends and musical community.1 Recent recordings have rekindled interest from listeners and critics alike in the works of this key fgure in mid-twentieth-century Soviet music. Vissarion Yakovlevich Shebalin was born in Omsk, the capital of Siberia, on 11 June 1902. His parents, both teachers, were utterly devoted to music. When he was eight years old, he began to learn the piano. By the age of ten he was a student in the piano class of the Omsk Division of the Russian Musical Society. Here he developed a love of composition. In 1919 he completed his studies at middle school and entered the Institute of Agriculture – the only local university at that time. When a music college opened in Omsk in 1921, Shebalin joined immediately, studying theory and composition with Mikhail Nevitov, a former pupil of Reinhold Glière. In 1923 he was accepted into Nikolai Myaskovsky’s composition class at the Moscow Conservatoire. His frst pieces, consisting of some romances and a string quartet, received favourable reviews in the press. Weekly evening concerts organised by the Association of 1 ‘To the Memory of a Friend’, in Valeria Razheava (ed.), Shebalin: Life and Creativity, Molodaya Gvardiya, Moscow, 2003, pp. -

Íride MARTÍNEZ, Soprano

BALMER & DIXON MANAGEMENT AG Kreuzstrasse 82, CH 8032 Zürich, Tel: 0041 43 244 86 44, Fax: 0041 43 244 86 49, [email protected] Íride MARTÍNEZ, Soprano Performances at La Scala, the Paris Bastille, Berlin State Opera or London’s Covent Garden: The native Costa Rican soprano Íride Martínez has travelled the world with international success. With her exceptional technique, versatility and acting talent Íride Martínez presents different roles of different styles and eras. Íride Martínez began her musical education in her native country Costa Rica. Then she had the unique opportunity to go to Europe. There celebrities such as Mirella Freni, Elio Battaglia and Wilma Lipp have taught her in acting and singing. For a Costa Rican, this is then as now inconceivable. Therefore Íride Martínez is for many of her fellow countrymen a great symbol. In 2014 she celebrated her 20th stage anniversary. Recent appearances include her long awaited Japan debut with the Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra touring through the country's most important concert halls with Beethoven's SYMPHONY NO. IX, further, again an invitation to Semperoper Dresden as Fiakermilli in ARABELLA under Christian Thielemann. Until 2016, Íride was a member of the Vienna State Opera where she excelled as Queen of the night, Gilda and especially as Marie in LA FILLE DU RÉGIMENT side by side with star tenor Juan Diego Flórez. After her debut with Norina in DON PASQUALE in 1994 at the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma, from 1995 to 2002 Íride was a permanent member of the ensemble at the Cologne Opera. For her Viola/Cesario at the World Premiere of WAS IHR WOLLT by M.