The Thief of Michelangelo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

The Master of the Unruly Children and his Artistic and Creative Identities Hannah R. Higham A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines a group of terracotta sculptures attributed to an artist known as the Master of the Unruly Children. The name of this artist was coined by Wilhelm von Bode, on the occasion of his first grouping seven works featuring animated infants in Berlin and London in 1890. Due to the distinctive characteristics of his work, this personality has become a mainstay of scholarship in Renaissance sculpture which has focused on identifying the anonymous artist, despite the physical evidence which suggests the involvement of several hands. Chapter One will examine the historiography in connoisseurship from the late nineteenth century to the present and will explore the idea of the scholarly “construction” of artistic identity and issues of value and innovation that are bound up with the attribution of these works. -

Emmaus Doctrinal Papers

EMMAUS DOCTRINAL PAPERS Emmaus Doctrinal Papers are a comprehensive compilation of important Biblical subjects. They are invaluable to a counselor who wants to answer questions, clarify a subject, or furnish additional information to his student. You may ask the Home Office to send the student a copy of any of the papers by indicating the number and letter on the TAB. If you would like a copy of any paper for yourself, please request it on the Request for Supplies form. 1. ANGELS a. Angelology 2. BAPTISM a. Water Baptism b. Baptism of Infants 3. BIBLE a. How Do We Know the Bible Is Complete? b. Bible Translations c. Bibliology Revelation/ Illumination/ Inspiration 4. CAPITAL PUNISHMENT a. Capital Punishment - Scriptural? 5. DANCING a. Dancing - a Sin? 6. DEATH a. Death b. Accountability after Death of Babies, Children, Still Born c. Accountability after Death of Children and "Childlike" Retarded 7. DISCIPLES/APOSTLES a. What Is a Disciple? b. Apostles’ Authority 8. DRUGS a. Drug Usage 9. ELECTION/PREDESTINATION a. Explain Election/Explain Predestination 10. EMMAUS a. Denomination? 11. ETERNAL SECURITY a. Hebrews 10 Explained b. Eternal Security (Radio Bible Class) 12. EVOLUTION a. Evolution 13. FAITH a. Faith ABOUT vs. Faith IN Christ b. What Is Faith (O.J. Smith) 14. FASTING a. Teaching of N.T. Concerning Fasting b. Fasting (Scripture Ref. & Note) 15. GOD a. Theology Proper b. Where Is God? Is God Dead? c. Can God Be Seen by Man? d. Does Everyone Hear of God? 16. HEALING a. Healing (Through Faith? Working?) b. Some Notes on Sickness, Infirmities, and Healing 17. -

Tuccia and Her Sieve: the Nachleben of the Vestal in Art

KU LEUVEN FACULTY OF ARTS BLIJDE INKOMSTSTRAAT 21 BOX 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË Tuccia and her sieve: The Nachleben of the Vestal in art. Sarah Eycken Presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Supervisor: prof. dr. Barbara Baert Lector: Katlijne Van der Stighelen Academic year 2017-2018 371.201 characters (without spaces) KU LEUVEN FACULTY OF ARTS BLIJDE INKOMSTSTRAAT 21 BOX 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË I hereby declare that, in line with the Faculty of Arts’ code of conduct for research integrity, the work submitted here is my own original work and that any additional sources of information have been duly cited. I! Abstract This master dissertation on the Nachleben in art of the Vestal Tuccia and her sieve, tries to chart the motif’s course throughout the history of art, using a transhistorical approach excluding an exhaustive study which lies outside the confines of this paper. Nevertheless, different iconographical types of the representations of Tuccia, as well as of their relative importance, were established. The role of Tuccia in art history and, by ex- tension, literature, is not very substantial, but nonetheless significant. An interdisciplinary perspective is adopted with an emphasis on gender, literature, anthropology and religion. In the Warburgian spirit, the art forms discussed in this dissertation are various, from high art to low art: paintings, prints, emblemata, cas- soni, spalliere, etc. The research starts with a discussion on the role of the Vestal Virgins in the Roman Re- public. The tale of the Vestal Virgin Tuccia and her paradoxically impermeable sieve, which was a symbol of her chastity, has spoken to the imagination of artists throughout the ages. -

The Parousia

The Parousia A Careful Look at the New Testament Doctrine of our Lord’s Second Coming, By James Stuart Russell By James Stuart Russell Originally digitized by Todd Dennis beginning in 1996 TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGH PRAISE FOR "THE PAROUSIA" PREFACE TO THE BOOK INTRODUCTORY. THE LAST WORDS OF OLD TESTAMENT PROPHECY. THE BOOK OF MALACHI The Interval between Malachi and John the Baptist PART I. THE PAROUSIA IN THE GOSPELS. THE PAROUSIA PREDICTED BY JOHN THE BAPTIST The Teaching of our Lord Concerning the Parousia in the Synoptical Gospels:- Prediction of Coming Wrath upon that Generation Further allusions to the Coming Wrath Impending fate of the Jewish nation (Parable of the Barren Fig-tree) The End of the Age, or close of the Jewish dispensation (Parables of Tares and Drag-net) The Coming of the Son of Man (the Parousia) in the Lifetime of the Apostles The Parousia to take place within the Lifetime of some of the Disciples The Coming of the Son of man certain and speedy (Parable of the Importunate Widow) The Reward of the Disciples in the Coming AEon, i.e. at the Parousia Prophetic Intimations of the approaching Consummation of the Kingdom of God:- i. Parable of the Pounds ii. Lamentation of Jesus over Jerusalem iii. Parable of the Wicked Husbandman iv. Parable of the Marriage of the King's Son v. Woes denounced on the Scribes and Pharisees vi. Lamentation (second) of Jesus over Jerusalem vii. The Prophecy on the Mount of Olives The Prophecy on the Mount examined:- I. Interrogatory of the Disciples II. -

Donatello's Terracotta Louvre Madonna

Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Sandra E. Russell May 2015 © 2015 Sandra E. Russell. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning by SANDRA E. RUSSELL has been approved for the School of Art + Design and the College of Fine Arts by Marilyn Bradshaw Professor of Art History Margaret Kennedy-Dygas Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract RUSSELL, SANDRA E., M.A., May 2015, Art History Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning Director of Thesis: Marilyn Bradshaw A large relief at the Musée du Louvre, Paris (R.F. 353), is one of several examples of the Madonna and Child in terracotta now widely accepted as by Donatello (c. 1386-1466). A medium commonly used in antiquity, terracotta fell out of favor until the Quattrocento, when central Italian artists became reacquainted with it. Terracotta was cheap and versatile, and sculptors discovered that it was useful for a range of purposes, including modeling larger works, making life casts, and molding. Reliefs of the half- length image of the Madonna and Child became a particularly popular theme in terracotta, suitable for domestic use or installation in small chapels. Donatello’s Louvre Madonna presents this theme in a variation unusual in both its form and its approach. In order to better understand the structure and the meaning of this work, I undertook to make some clay works similar to or suggestive of it. -

I Just Can't Bring Myself to Join

just can’t bring myself to join the crowd crying out, “Crucify Ihim!” I want to hang on to the opening gospel and continue to shout, “Hosanna, Hosanna!” We begin Mass today glorifying Jesus and end it killing him. So which person are we: Christ’s disciples or his executioners? Sometimes we act with the humility of the beatitudes, Forgiveness abounds other times with the egocentricity Volunteers offer strength for the journey of the unchurched. This is the very reason we walk our Lenten Dismas House Ministry volunteers enjoyed a Mass said by Archbishop journey: to be enlightened of this Wilton Gregory at the transition facility. dichotomy and ach Thursday, a carload of yearly, said Jo Simon, the ministry freed from our ESt. Ann parishioners makes leader at St. Ann. The volunteers, personal failings. its way around Interstate 285 for she said, are a consistent reminder Today we an appointment. These Dismas that there are people in the enter Holy Week, Ministry volunteers seek to community who will be there for the most sacred encourage, inspire and motivate them. of times for people transitioning from “I particularly enjoy the direct Christians and Reflection incarceration back into normal life. interaction with Dismas residents,” an intense and Deacon Keith Kolodziej “Everyone makes mistakes,” said Melise Etheridge. “I know we final preparation said Christine Holt, “some more make an impact on their lives with for Easter. Take the time to join severe than others. However, Christ our classes [because] many relay your community on Holy Thursday demands that we all seek and give their success stories to us. -

Holy Monday St. John 12:1-23 March 29Th, 2021 Sts. Peter and Paul Evangelical Lutheran Church, UAC Simpsonville, SC Pastor Jerald Dulas

Holy Monday St. John 12:1-23 March 29th, 2021 Sts. Peter and Paul Evangelical Lutheran Church, UAC Simpsonville, SC Pastor Jerald Dulas Mary Anointed the Feet of Jesus In Nomine Iesu! In the Name of the Father and of the + Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen. Prayer in Pulpit before Sermon: O Lord, send out Thy Light and Thy Truth, let them lead us. O Lord, open Thou my lips, that my mouth may show forth Thy praise. O Lord, graciously preserve me, lest that by any means, when I have preached to others, I myself should be rejected. Amen. Grace, mercy, and peace be to you from God our Father and from our Lord and Savior + Jesus Christ. Amen. From the crowds rejoicing and cheering our Lord + Jesus into Jerusalem in yesterday’s Gospel, we are taken to our Lord’s suffering and burial. Indeed, we will be presented with our Lord’s Passion every day this week as we approach Good Friday and the crucifixion of our Lord on the tree of the holy cross for the atonement of the whole world and the justification of all those who cling to this work of Him in faith. We are taken to the death of our Lord + Jesus by Mary, the sister of Martha, and even more significant, the sister of Lazarus, who was risen from the dead by the Lord + Jesus. Mary takes us to our Lord’s death and burial, because she anoints the feet of our Lord with very costly—three hundred denarii worth—spikenard. -

St. Elijah Orthodox Christian Church

ST. ELIJAH ORTHODOX CHRISTIAN CHURCH 15000 N. May, Oklahoma City, OK 73134 Church Office: 755-7804 Church Website: www.stelijahokc.com Church Email: [email protected] APRIL 5, 2020 Issue 32 Number 14 Fifth Sunday of Great Lent (Commemoration of our Righteous Mother Mary of Egypt); Saints of the Day: Martyrs Claudius, Diodore and their companions; New-Martyr George of New Ephesus; Venerable Theodora and Didymus of Alexandria DIRECTORY WELCOME V. Rev. Fr. John Salem Parish Priest 410-9399 We welcome all our visitors. It is an honor to have you worshipping with us. You may find the worship of the Rev. Fr. Elias Khouri Ancient Church very different. We welcome your questions. Assistant Priest 640-3016 Please join us for our Reception held in the Church Hall V. Rev. Fr. Constantine Nasr immediately following the Divine Liturgy. Emeritus We understand Holy Communion to be an act of our unity in Rev. Dn. Ezra Ham faith. While we work toward the unity of all Christians, it Administrator 602-9914 regrettably does not now exist. Therefore, only baptized Rev. Fr. Ambrose Perry Orthodox Christians (who have properly prepared) are Attached permitted to participate in Holy Communion. However, everyone is welcome to partake of the blessed bread that is Anthony Ruggerio 847-721-5192 distributed at the end of the service. We look forward to Youth Director meeting you during the Reception that follows the service. Mom’s Day Out & Pre-K NEW ORTHROS & LITURGY BOOK Sara Cortez – Director 639-2679 Orthros: p. 4 Email: [email protected] Facebook: “St Elijah Mom’s Day Out” The Divine Liturgy p. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

Light, Life, and Love

Light, Life, and Love Author(s): Inge, William Ralph (1860-1954) Eckhart, Johannes (c. 1260-1327) (Author of section) Tauler, John (c. 1300-1361) (Author of section) Suso, Henry (c. 1296-1366) (Author of section) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: This book has everything a reader needs to explore the world of German mysticism. William Inge begins with an introduc- tion of histories, biographies, and summaries of the move- ment, and his scholarly articles will prove useful for the stu- dent of mysticism. Then he includes in the book many ex- amples of the writings of the 14th century Dominicans, the Friends of God. These friends were an informal group of Catholics who strove to deepen both their communal relation- ships as well as their inner spirituality. Eckhardt, Tauler, and Suso were the major proponents of this theology, and each is represented in Inge©s collection.This book is a unique and convenient volume that will assist readers interested in the fascinating movement of German mysticism. Abby Zwart CCEL Staff Writer Subjects: Practical theology Practical religion. The Christian life Mysticism i Contents Title Page 1 Table of Contents 2 Introduction 3 1. The Precursors of the German Mystics 4 2. Meister Eckhardt 7 3. Eckhardt's Religious Philosophy 10 4. The German Mystics as Guides to Holiness 19 5. Writers of the School of Eckhard–Tauler 21 6. Suso 22 7. Ruysbroek 24 8. Theologia Germanica 25 9. Modern Mysticism 26 10. Specimens of Modern Mysticism 28 Light, Life and Love 31 Eckhardt -

Michelangelo's David-Apollo

Michelangelo’s David-Apollo , – , 106284_Brochure.indd 2 11/30/12 12:51 PM Giorgio Vasari, Michelangelo Michelangelo, David, – Buonarroti, woodcut, from Le vite , marble, h. cm (including de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e base). Galleria dell’Accademia, architettori (Florence, ). Florence National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, Gift of E. J. Rousuck The loan of Michelangelo’s David-Apollo () from a sling over his shoulder. The National Gallery of Art the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, to the owns a fteenth-century marble David, with the head of National Gallery of Art opens the Year of Italian Culture, Goliath at his feet, made for the Martelli family of Flor- . This rare marble statue visited the Gallery once ence (. ). before, more than sixty years ago, to reafrm the friend- In the David-Apollo, the undened form below the ship and cultural ties that link the peoples of Italy and right foot plays a key role in the composition. It raises the United States. Its installation here in coincided the foot, so that the knee bends and the hips and shoul- with Harry Truman’s inaugural reception. ders shift into a twisting movement, with the left arm The ideal of the multitalented Renaissance man reaching across the chest and the face turning in the came to life in Michelangelo Buonarroti ( – ), opposite direction. This graceful spiraling pose, called whose achievements in sculpture, painting, architecture, serpentinata (serpentine), invites viewers to move and poetry are legendary (. ). The subject of this around the gure and admire it from every angle. Such statue, like its form, is unresolved. -

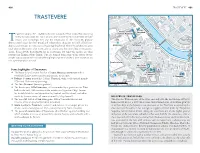

Trastevere (Map P. 702, A3–B4) Is the Area Across the Tiber

400 TRASTEVERE 401 TRASTEVERE rastevere (map p. 702, A3–B4) is the area across the Tiber (trans Tiberim), lying below the Janiculum hill. Since ancient times there have been numerous artisans’ Thouses and workshops here and the inhabitants of this essentially popular district were known for their proud and independent character. It is still a distinctive district and remains in some ways a local neighbourhood, where the inhabitants greet each other in the streets, chat in the cafés or simply pass the time of day in the grocery shops. It has always been known for its restaurants but today the menus are often provided in English before Italian. Cars are banned from some of the streets by the simple (but unobtrusive) method of laying large travertine blocks at their entrances, so it is a pleasant place to stroll. Some highlights of Trastevere ª The beautiful and ancient basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere with a wonderful 12th-century interior and mosaics in the apse; ª Palazzo Corsini, part of the Gallerie Nazionali, with a collection of mainly 17th- and 18th-century paintings; ª The Orto Botanico (botanic gardens); ª The Renaissance Villa Farnesina, still surrounded by a garden on the Tiber, built in the early 16th century as the residence of Agostino Chigi, famous for its delightful frescoed decoration by Raphael and his school, and other works by Sienese artists, all commissioned by Chigi himself; HISTORY OF TRASTEVERE ª The peaceful church of San Crisogono, with a venerable interior and This was the ‘Etruscan side’ of the river, and only after the destruction of Veii by remains of the original early church beneath it; Rome in 396 bc (see p.