Conflict, Consensus, and Circulation the Public Debates on Education in Sweden, C.1800–1830 Hammar, Isak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the History of Naming the North Sea

On the History of Naming the North Sea Bela Pokoly (Commission on Geographical Names, Ministry of AgricuUUfe and Regional Development, Department of Lands and Mapping, Hungary) The North Sea - where it is - how it grew in importance The sea is situated in the northern part of Western Europe roughly between the eastern coast of Britain, the 61st parallel in the North, the southern coasts of Norway, a small part of the SE coast of Sweden, the western shores of Denmark, the north- western coasts of Gennany. as well as those of [he Netherlands and Belgium, with a tiny French coastal part (around Dunquerque). Its area is about 225 thousand sq. miles, a little more than the land area of France. Being a shallow sea (overwhelmingly covering the continental shelves except in the Norwegian Trench where at one point it is almost 400 fathoms deep) it also holds a relatively small amount of water. Fig. L {slide} The North Sea belongs to the better-known seas not only in Europe, but throughout the world. Its familiarity has especially grown at great scales smce the 1970's as output of petroleum and natural gas from its continental shelf achieved global importance. As the Hungarian scholar of geography M. Haltenberger wrote in his book Marine Geography (1965) the rough waters of the sea had been avoided by both the Romans and traders of the Hanseatic League. The importance of the sea started to grow only after the great discoveries as the Atlantic Ocean became the "Mediterranean Sea of the new times". - 4 - % , '." Earliest occurrences of the name of the sea Prehistoric people moved little from the area they inhabited, therefore, if it was a seacoast, they called the sea without any specific name, just "the sea", [n later times, when people realized that their sea was not the only one, did they begin to give specific names to seas, The ancient Greek scholar Strabon, who lived between 60 B,C. -

Wittenberger Einflüsse Auf Die Reformation in Skandinavien Von Simo Heininen, Otfried Czaika

Wittenberger Einflüsse auf die Reformation in Skandinavien von Simo Heininen, Otfried Czaika Wittenberg war der wichtigste Impulsgeber für die Reformation in den beiden skandinavischen Reichen, dem dänischen und dem schwedischen Reich. In beiden Reichen war die Reformation stark vom Einfluss der Obrigkeiten geprägt, al- lerdings verlief sie in den beiden frühneuzeitlichen Staaten sehr unterschiedlich. Am raschesten wurde das Reformati- onswerk politisch wie kirchenrechtlich im dänischen Kernland gesichert; Schweden dagegen war zwar de facto bereits vor 1550 ein lutherisches Land, de jure jedoch erst im letzten Jahrzehnt des 16. Jahrhunderts. Besonders in den eher peripheren Teilen Skandinaviens, insbesondere Norwegen und Island, ging die Reformation Hand in Hand mit einer poli- tischen Gleichschaltung von Skandinavien und wurde deshalb entsprechend zaghaft von der Bevölkerung angenommen. INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. Politische Hintergründe 2. Dänemark 3. Norwegen und Island 4. Schweden 5. Finnland 6. Zusammenfassung 7. Anhang 1. Quellen 2. Literatur 3. Anmerkungen Indices Zitierempfehlung Politische Hintergründe Seit dem Jahre 1397 waren die Königreiche Dänemark, Norwegen und Schweden in Personalunion (der sogenannten Kalmarer Union) unter dänischer Führung vereint (ᇄ Medien Link #ab). Anfang des 16. Jahrhunderts war die Union dem Ende nahe – es gab zunehmende Spannungen zwischen Dänemark und Schweden, das von Reichsverwesern aus dem Hause Sture regiert wurde. Im November 1520 wurde Christian II. von Dänemark (1481–1559) (ᇄ Medien Link #ac), der letzte Unionskönig, ein zweites Mal in Stockholm gekrönt. Nach den Krönungsfeierlichkeiten inszenierte man mit der Hilfe des Erzbischofs von Uppsala einen Ketzerprozess gegen die Anhänger der Sture-Partei. Infolgedessen wurden zwei Bischöfe, mehrere Unionsgegner aus dem Adel sowie zahlreiche Stockholmer Bürger hingerichtet. Der junge Edel- mann Gustav Vasa (1496–1560) (ᇄ Medien Link #ad) erhob die Fahne des Aufruhrs. -

Sources of the First Printed Scandinavian Runes

Runrön Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet 24 Fischnaller, Andreas, 2021: Sources of the First Printed Scandinavian Runes. In: Reading Runes. Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium on Runes and Runic Inscriptions, Nyköping, Sweden, 2–6 September 2014. Ed. by MacLeod, Mindy, Marco Bianchi and Henrik Williams. Uppsala. (Runrön 24.) Pp. 81–93. DOI: 10.33063/diva-438869 © 2021 Andreas Fischnaller (CC BY) ANDREAS FISCHNALLER Sources of the First Printed Scandinavian Runes Abstract The aim of this paper is to shed some light on the sources that were used for the first printed Scandinavian runes. These runes appear in works published in Italy between 1539 and 1555 either by or in connection with Johannes and Olaus Magnus. The books and the information about runes and runic inscriptions they contain are presented first. A closer look is then taken at the shapes of the runes used and at the roman letters they represent according to the books. It will be shown that these runes and their sound values can in part be traced back to a mediaeval runic tradition, while others were created to provide at least one rune for every roman letter. The forms of the newly “invented” runes can be explained to some extent by the influence of the shape of the roman letters they represent, whereas others were taken from a source that contained runes but did not provide any information about their sound values, namely the runic calendars. Keywords: Olaus Magnus, Theseus Ambrosius, Bent Bille, Renaissance, printed runes, q-rune, x-rune, belgþór-rune Introduction Work with post-reformation runic inscriptions has long been a neglected area of runology.1 A glance through the most common introductions to the study of runes reveals our lack of certainty as regards when runes stopped being used and how knowledge of runes was preserved (cf. -

Ocean Eddies in the 1539 Carta Marina by Olaus Magnus

Ocean Eddies in the 1539 Carta Marina by Olaus Magnus H. Thomas Rossby 5912 LeMay Road, Rockville, MD 20851-2326, USA. Road, 5912 LeMay The Oceanography machine, reposting, or other means without prior authorization of portion photocopy of this articleof any by Copyrigh Society. The Oceanography journal 16, Number 4, a quarterly of Volume This article in Oceanography, has been published University of Rhode Island • Narragansett, Rhode Island USA Peter Miller Plymouth Marine Laboratory • Plymouth UK In 1539 Olaus Magnus, an exiled Swedish priest of maps to aid navigators grew enormously. From the living in Italy, published a remarkably detailed map of Atlantic in the west to the Black and Red Seas in the east, the Nordic countries, from Iceland in the west to these maps of the Mediterranean depict the shape and Finland in the east. The map, called ‘Carta Marina’, proportions of the Mediterranean Sea quite well. Any introduced a scope of information about these coun- one familiar with reading maps will recognize Gibraltar, tries that broke completely new ground in terms of Italy, the Balkans, Egypt and Palestine. Many include the comprehensiveness and general accuracy. The geo- British Isles and Germany, but not Scandinavia. In the graphical outline of the Nordic countries is quite accu- early editions of the Ptolemy atlas Scandinavia does not rate and the map includes all the major island groups appear. But in 1482 Nicolaus Germanus (the Ulm atlas) such as the Faroes, Orkneys and Shetland Islands. In drew a map in which Denmark, southern Sweden and addition to the geography and numerous ethnograph- Norway clearly appear with names of numerous regions ic sketches, the map also provides, as it name indicates, and towns. -

N: a Sea Monster of a Research Project

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects Honors Program 5-2019 N: A Sea Monster of a Research Project Adrian Jay Thomson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Thomson, Adrian Jay, "N: A Sea Monster of a Research Project" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. 424. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/424 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. N: A SEA MONSTER OF A RESEARCH PROJECT by Adrian Jay Thomson Capstone submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with UNIVERSITY HONORS with a major in English- Creative Writing in the Department of English Approved: UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT SPRING2019 Abstract Ever since time and the world began, dwarves have always fought cranes. Ever since ships set out on the northern sea, great sea monsters have risen to prey upon them. Such are the basics of life in medieval and Renaissance Scandinavia , Iceland, Scotland and Greenland, as detailed by Olaus Magnus' Description of the Northern Peoples (1555) , its sea monster -heavy map , the Carta Marina (1539), and Abraham Ortelius' later map of Iceland, Islandia (1590). I first learned of Olaus and Ortelius in the summer of 2013 , and while drawing my own version of their sea monster maps a thought hit me: write a book series , with teenage characters similar to those in How to Train Your Dragon , but set it amongst the lands described by Olaus , in a frozen world badgered by the sea monsters of Ortelius. -

Wittenberg Influences on the Reformation in Scandinavia by Simo Heininen, Otfried Czaika

Wittenberg Influences on the Reformation in Scandinavia by Simo Heininen, Otfried Czaika Wittenberg was the most important source of inspiration for the Reformation in both of the Scandinavian kingdoms, the Danish kingdom and the Swedish kingdom. In both kingdoms, the authorities played a defining role in the Reformation, though it proceeded very differently in these two Early Modern states. The Reformation became securely established most quickly – both politically and in terms of church law – in the Danish core territory. Sweden, on the other hand, was de facto already a Lutheran country before 1550, though it did not become Lutheran de jure also until the last decade of the 16th century. Particularly in the peripheral parts of Scandinavia (especially Norway and Iceland), the Reformation went hand in hand with closer political integration in Scandinavia and it was therefore adopted rather reluctantly by the population. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Political Background 2. Denmark 3. Norway and Iceland 4. Sweden 5. Finland 6. Conclusion 7. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Bibliography 3. Notes Indices Citation Political Background From 1397, the kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden were united in a personal union (the so-called Kalmar Union) under Danish control (ᇄ Media Link #ab). In the early-16th century, the union was approaching its end. There were increasing tensions between Denmark and Sweden, the latter being governed by regents from the House of Sture. In November 1520, Christian II of Denmark (1481–1559) (ᇄ Media Link #ac), the last union king, was crowned for a second time in Stockholm. After the coronation festivities had been concluded, a heresy trial was staged with the help of the Archbishop of Uppsala and the accused were the supporters of the Sture party. -

Maps and the Early Modern State: Official Cartography Richard L

26 • Maps and the Early Modern State: Official Cartography Richard L. Kagan and Benjamin Schmidt Introduction: Kings ing and enhancing political authority, and it quickly be- and Cartographers comes apparent from later correspondence that Charles wanted from his cosmógrafo mayor not simply knowl- In 1539, the emperor Charles V, waylaid by gout, was edge but also “power” in the form of cartographic prod- obliged to spend much of the winter in the city of Toledo ucts useful to his regime. In 1551, Santa Cruz happily re- in the heart of Castile. To help pass the time, Europe’s ported to the king the completion of a new map of Spain, most powerful monarch asked Alonso de Santa Cruz, a “which is about the size of a large banner (repostero) and royal cosmographer and one of the leading mapmakers of which indicates all of the cities, towns, and villages, sixteenth-century Spain, to teach him something of his mountains and rivers it has, together with the boundaries craft and of those subjects that supported his work. A of the [various Spanish] kingdoms and other details”— number of years later, Santa Cruz would recall how the just the thing for an ambitious ruler like Charles V.2 Fi- emperor “spent most days with me, Alonso de Santa nally, the emperor’s cartographic tutorials point to an- Cruz, royal cosmographer, learning about matters of as- other, equally vital, role of maps in the early modern trology, the earth, and the theory of planets, as well as sea European court, namely their ability to bring “pleasure charts and cosmographical globes, all of which gave him and joy” to their royal patron. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] [Russia, Sweden, Finland, Estonia Latvia and Lithuania]. Stock#: 36638 Map Maker: Gastaldi Date: 1562 Place: Venice Color: Uncolored Condition: VG Size: 21.5 x 15 inches Price: $ 11,000.00 Description: A fine wide margined example of the northern sheet of the first edition of Gastaldi's 2-sheet map covering Russia, Sweden, Finland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, published in Venice in 1562. The present offering is the northern sheet only (of 2) of Gastaldi's Desegno de Geographia Moderna Del Regno di Polonia, e parte Del Ducado di Moscovia. It embraces all of eastern Sweden (north of Gotland), the entire Gulf of Bothnia, the vast majority of Finland, and much of Northwestern Russia, as well as Estonia, Latvia, and the northern parts of Lithuania. The map's southern sheet extended to include Poland and much of the Ukraine down to and including Crimea, please see: {{ inventory_detail_link('32237') }} The present northern sheet is nevertheless an extremely important map for Russia, Finland, Sweden and the Baltic Countries. It is the earliest Lafreri School map to focus on the region and among the earliest obtainable maps to depict modern cartographic details, rather than simply relying upon Ptolemy either entirely or as the major basis for the geographical content. The geography of this map was largely derived from Gerhard Mercator's 1554 map of Europe, but also takes account of some other advanced sources. The detail with respect to the shorelines of Scandinavia and the lake and river systems of Russia is impressive. -

Some Landmarks in Icelandic Cartography Down to the End of The

ARCTIC VOL. 37, NO. 4 (DECEMBER 198-4) P. 389-401 Some Landmarks in.keland-ic. Cartography down to the End of the Sixteenth Century HARALDUR. SIGURDSSON* Sometime between 350.and 310 B.C., it is thought, a Greek Adam of Bremen,and Sax0 ,Grammaticus both considered navigator, F‘ytheas of Massilia .(Marseilles), after a sail of six Iceland and Thule to be the same country. Adam is quite ex- daysfrom the British Isles, came to anunknown country plicit on the point:“This Thule is now named Iceland from the which hemmed Thule. The sources relating.to this voyageare ice which bind the sea” (von .Bremen, 1917:IV:36; Olrik and fragmentary and less explicit than one might wish. ‘The infor- Raeder, 1931:7). When the ,Icelanders themselves.began to mationis taken from its original contextand distorted in write about their country (Benediktsson, 1968:31) they were various ways. No one knows what country it wasthat F‘ytheas quite certain that Iceland was the same country as that which came upon farthest from his native shore, and most of the the Venerable Bede called by the name of Thule. .North Atlantic countries have been designated as .candidates. Oldest among .the maps on which Iceland is shown is the But in the.form in which it has come downto us, Pytheas’sac- Anglo-Saxon map, believed to have been made somewhere count does not, in reality, fit ,any of them. His voyage ‘will around the year 1OOO. If that dating is approximatelyright, this always remain one of the insoluble riddles of geographical is the first knownOccurrence in writing of the name history. -

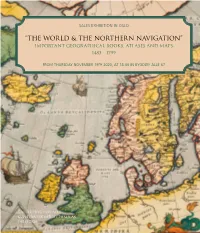

“The World & the Northern Navigation”

SALES EXHIBITION IN OSLO “THE WORLD & THE NORTHERN NAVIGATION” IMPORTANT GEOGRAPHICAL BOOKS, ATLASES AND MAPS 1483 – 1799 FROM THURSDAY NOVEMBER 19TH 2020, AT 18.00 IN BYGDØY ALLÉ 67 GALLERI BYGDØY ALLÉ KUNSTANTIKVARIAT PAMA AS OSLO 2020 SALES EXHIBITION IN OSLO “THE WORLD & THE NORTHERN NAVIGATION” IMPORTANT GEOGRAPHICAL BOOKS, ATLASES AND MAPS 1483 – 1799 IN OUR EXHIBITION ROOMS, BYGØY ALLÉ 67 FROM THURSDAY NOVEMBER 19th, 2020 AT 6PM UNTIL DECEMBER 23 Tuesday – Friday 12 – 18, Saturday & Sunday 12 – 16 By appointment only, see below Tel: (+47) 928 18 465 • [email protected] NB! Due to the current covid-19 situation please contact us prior to your visit. This will help us to keep the necessary restrictions and the number of people. NB! Grunnet covid-19 og fortsatt stor aktsomhet rundt sosial omgang, ber vi om at våre kunder melder seg til oss på forhånd. Dette for å sikre et forsvarlig antall personer hos oss til enhver tid. Catalogue entry no. 23 Front cover: Abraham Ortelius «Septentrionalium Regionum Descrip» Antwerp 1575 A superb copy in fresh original colours 3 INDEX IMPORTANT GEOGRAPHICAL BOOKS AND ATLASES 1483 - 1799 ................................ page 6 RARE ANTIQUE MAPS OF THE WORLD AND THE NORTH 1493 – 1709 ..................... page 36 L.J. WAGHENAER: FROM VESTFOLD AND OSLO FJORD DOWN TO THE SOUND Amsterdam or Leiden c. 1601 Rare and important chart TERMS AND EXPLANATIONS All items have been carefully described and are guaranteed to be genuine and authentic. The prices are in NOK (Norwegian kroner), all taxes included. As an indication only, the items are also priced in EURO after an approximate exchange rate of 1€ = NOK 10.75 Contemporary hand-coloured: In our opinion, the colouring is approximately contemporary with the date of issue. -

Ocean Eddies in the 1539 Carta Marina by Olaus Magnus

82716_Ocean 12/18/03 6:26 PM Page 77 Ocean Eddies in the 1539 Carta Marina by Olaus Magnus H. Thomas Rossby University of Rhode Island • Narragansett, Rhode Island USA Peter Miller Plymouth Marine Laboratory • Plymouth UK In 1539 Olaus Magnus, an exiled Swedish priest of maps to aid navigators grew enormously. From the living in Italy, published a remarkably detailed map of Atlantic in the west to the Black and Red Seas in the east, the Nordic countries, from Iceland in the west to these maps of the Mediterranean depict the shape and Finland in the east. The map, called ‘Carta Marina’, proportions of the Mediterranean Sea quite well. Any introduced a scope of information about these coun- one familiar with reading maps will recognize Gibraltar, tries that broke completely new ground in terms of Italy, the Balkans, Egypt and Palestine. Many include the comprehensiveness and general accuracy. The geo- British Isles and Germany, but not Scandinavia. In the graphical outline of the Nordic countries is quite accu- early editions of the Ptolemy atlas Scandinavia does not rate and the map includes all the major island groups appear. But in 1482 Nicolaus Germanus (the Ulm atlas) such as the Faroes, Orkneys and Shetland Islands. In drew a map in which Denmark, southern Sweden and addition to the geography and numerous ethnograph- Norway clearly appear with names of numerous regions ic sketches, the map also provides, as it name indicates, and towns. An updated version of this map was com- an extraordinary wealth of information about the piled by Martin Waldseemüller in 1513. -

Visions of North in Premodern Europe CURSOR MUNDI

Visions of North in Premodern Europe CURSOR MUNDI Cursor Mundi is produced under the auspices of the Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, University of California, Los Angeles. Executive Editor Blair Sullivan, University of California, Los Angeles Editorial Board Michael D. Bailey, Iowa State University Christopher Baswell, Columbia University and Barnard College Florin Curta, University of Florida Elizabeth Freeman, University of Tasmania Yitzhak Hen, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Lauren Kassell, Pembroke College, Cambridge David Lines, University of Warwick Cary Nederman, Texas A&M University Teofilo Ruiz,University of California, Los Angeles Previously published volumes in this series are listed at the back of the book. Volume 31 © BREPOLS PUBLISHERS THIS DOCUMENT MAY BE PRINTED FOR PRIVATE USE ONLY. IT MAY NOT BE DISTRIBUTED WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. Visions of North in Premodern Europe Edited by Dolly Jørgensen and Virginia Langum British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. © 2018, Brepols Publishers n.v., Turnhout, Belgium All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. D/2018/0095/128 ISBN: 978-2-503-57475-2 e-ISBN: 978-2-503-57476-9 DOI:10.1484/M.CURSOR-EB.5.112872 Printed on acid-free paper © BREPOLS PUBLISHERS THIS DOCUMENT MAY