Woman of Valor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Introduction: “Meager Gifts” from “Desert Islands”

Introduction: “Meager Gifts” from “Desert Islands” American-Born Women and Hebrew Poetry SHACHAR PINSKER I Th is volume seeks to fi ll a signifi cant gap in Jewish American literature and Hebrew literature. In 2003 Alan Mintz wrote that “the existence of a substantial body of Hebrew literature written on American shores is one of the best-kept secrets of Jewish American cultural history.”1 A de cade later it seems that the secret of Hebrew literature in America has been revealed. In the last few years, many articles and three new scholarly books on American Hebrew literature have been published.2 With this renewed interest and abundance of new ma- terials, the story of American Hebrew literature is fi nally getting some of the attention it truly deserves. Nevertheless, there is a substantial lacuna in this fi eld, which has to do with the presence of women writers in this literary and cultural endeavor. Hebrew literature in America was written and read by a small minority of Jews, and yet Daniel Persky, a prominent Hebrew writer and journalist, counted in 1927 (the height of the movement) no fewer than 110 active writers of Hebrew in America.3 So where were the women writers in this number? After all, it was pre- cisely in the 1920s and 1930s that women began to be active in Hebrew literature, 1 INTRODUCTION mostly in poetry, in Europe and Palestine, as well as in Yiddish literature in America and Eu rope (and even Palestine). Indeed, until very recently scholars assumed that American Hebrew literature, which fl ourished between the 1900s and 1960s, had been the exclusive domain of East Euro pean immigrant men, as well as very few American- born writers (also men). -

Chana Kronfeld's CV

1 Kronfeld/CV CURRICULUM VITAE CHANA KRONFELD Professor of Modern Hebrew, Yiddish and Comparative Literature Department of Near Eastern Studies, Department of Comparative Literature and the Designated Emphasis in Jewish Studies 250 Barrows Hall University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 #1940 Home phone & fax (510) 845-8022; cell (510) 388-5714 [email protected] EDUCATION: Ph.D. 1983 University of California, Berkeley, Comparative Literature, Dissertation: “Aspects of Poetic Metaphor” MA 1977 University of California, Berkeley, Comparative Literature (with distinction) BA 1971 Tel Aviv University, Poetics and Comparative Literature; English (Summa cum laude) PRINCIPAL ACADEMIC INTERESTS: Modernism in Hebrew, Yiddish and English poetry, intertextuality, translation studies, theory of metaphor, literary historiography, stylistics and ideology, gender studies, political poetry, marginality and minor literatures, literature & linguistics, negotiating theory and close reading. HONORS AND FELLOWSHIPS: § 2016 – Finalist, Northern California Book Award (for The Full Severity of Compassion: The Poetry of Yehuda Amichai) § 2015 - Diller Grant for Summer Research, Center for Jewish Studies, University of California, Berkeley § 2014-15 Mellon Project Grant, University of California, Berkeley § 2014 - “The Berkeley School of Jewish Literature: Conference in Honor of Chana Kronfeld,” Graduate Theological Union and UC Berkeley, March 9, 2014 and Festschrift: The Journal of Jewish Identities, special issue: The Berkeley School of Jewish -

Ÿþm I C R O S O F T W O R

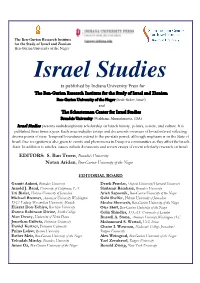

The Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Israel Studies is published by Indiana University Press for The Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (Sede-Boker, Israel) and The Schusterman Center for Israel Studies Brandeis University (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) Israel Studies presents multidisciplinary scholarship on Israeli history, politics, society, and culture. It is published three times a year. Each issue includes essays and documents on issues of broad interest reflecting diverse points of view. Temporal boundaries extend to the pre-state period, although emphasis is on the State of Israel. Due recognition is also given to events and phenomena in Diaspora communities as they affect the Israeli State. In addition to articles, issues include documents and review essays of recent scholarly research on Israel. EDITORS: S. Ilan Troen, Brandeis University Natan Aridan, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev EDITORIAL BOARD Gannit Ankori, Brandeis University Derek Penslar, Oxford University/Harvard University Arnold J. Band, University of California, LA Shulamit Reinharz, Brandeis University Uri Bialer, Hebrew University of Jerusalem Arieh Saposnik, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Michael Brenner, American University Washington Gabi Sheffer, Hebrew University of Jerusalem D.C/ Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich Moshe Shemesh, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Eliezer Don-Yehiya, Bar-Ilan University Ofer Shiff, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Donna Robinson Divine, Smith College Colin Shindler, S.O.A.S, University of London Alan Dowty, University of Notre Dame Russell A. Stone, American University, Washington, D.C. -

Choosing Yiddish New Frontiers of Language and Culture

Choosing Yiddish new frontiers of language and culture Edited by Lara Rabinovitch, Shiri Goren, and Hannah S. Pressman Wayne State University PressDetroit © 2013 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of America. 17 16 15 14 135 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Choosing Yiddish : new frontiers of language and culture / edited by Lara Rabinovitch, Shiri Goren, and Hannah S. Pressman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8143-3444-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) — isbn 978-0-8143-3799-8 (ebook) 1. Yiddish language—Social aspects.2. Yiddish literature—History and criticism.I. Rabinovitch, Lara, 1979–II. Goren, Shiri, 1976– III. Pressman, Hannah S., 1979– PJ5113.C46 2012 439′.1—dc23 2012015788 Hebrew Remembers Yiddish Avot Yeshurun’s Poetics of Translation adriana x. jacobs A few days aft er his death, the New York Times published a short obituary in honor of the Israeli poet Avot Yeshurun (1904–1992).1 The laconic headline “Poet in Unusual Idiom” accurately summed up a career that spanned most of twentieth century modern Hebrew and Israeli writing, one that encom- passed and articulated the various subjects, themes, questions, and polemics that preoccupied modern Hebrew poetry throughout the twentieth century, particularly with regard to language politics.2 Like many writers of his gen- eration, Yeshurun was not a native Hebrew speaker, and his poetry, like theirs, maps not only the linguistic shift s and transformations that occurred within modern Hebrew itself but also the long-standing tension between a “revived” Hebrew vernacular and native, diasporic languages, Yiddish in particular. -

The Desire for Nativeness in Hebrew Israeli Poetry

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 22 (2020) Issue 1 Article 2 "A Generation of Wonderful Jews Will Grow from the Land": The Desire for Nativeness in Hebrew Israeli Poetry Hamutal Tsamir Ben Gurion University of the Negev Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Tsamir, Hamutal. ""A Generation of Wonderful Jews Will Grow from the Land": The Desire for Nativeness in Hebrew Israeli Poetry." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 22.1 (): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.3716> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

Jewish Resistance in World War II & Zionism: Making Aliyah in the Death

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2017 Jewish Resistance in World War II & Zionism: Making Aliyah in the Death Camps Cierra Tomaso Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Tomaso, Cierra, "Jewish Resistance in World War II & Zionism: Making Aliyah in the Death Camps" (2017). University Honors Program Theses. 245. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/245 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jewish Resistance in World War II & Zionism: Making Aliyah in the Death Camps An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in History. By Cierra Tomaso Under the mentorship of Dr. Brian K. Feltman ABSTRACT My thesis examines the contributions of Jewish resistance fighters in Europe during World War II. The sources used are primarily memoirs of resistance fighters, primary documents from resistance groups, and secondary articles related to Zionism during that time period. The resistance movement began because there was a need for dismantling the Third Reich from within the bounds of the ghettos, the death camps, and the killing fields. This thesis will show that Zionism played a key role in the motivations of the Jewish resistance fighters in World War II. Additionally, it will examine how as Jews found that their home countries sought to cut ties with them, they found refuge in their new identity as Zionists. -

Introduction: Poetry in Israel: Forging Identity

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 22 (2020) Issue 1 Article 1 Introduction: Poetry in Israel: Forging Identity Chanita Goodblatt Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Goodblatt, Chanita. "Introduction: Poetry in Israel: Forging Identity." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 22.1 (): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.3700> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 0 times as of 04/28/ 20. -

2008 Program in Judaic Studies

FALL 2008 Program in Judaic Studies PERELMAN INSITITUE PRINCETON UNIVERSITY In this Issue 2 Courses DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE usual because of faculty leaves. In the fall of 2007 we sponsored, co-sponsored, or cross- 3 Students I was privileged to spend the entire academic listed nine courses in European Cultural 3 Class of 2008 year of 2007-2008 on leave at the Wissen- Studies, Comparative Literature, History, 3 Alumni 2008 schaftskolleg/Institute for Near Eastern Studies and Religion, plus four Advanced Study at Berlin, 4 Senior Theses 2008 Hebrew language courses. In the spring 7 Graduate Fellowships Germany. Leora Batnitzky of 2008 we offered ten courses (including 8 Graduate Students was kind enough to serve one graduate course), plus four courses in as acting director. She did a Hebrew language. They were cross-listed 11 Summer Funding great job, and most of what with American Studies, Center for Human 16 Special Highlights I am able to report is due Values, History, Near Eastern Studies, Music, 17 Committee Peter Schäfer to her efficient and tireless Religion, and Women and Gender Studies. 17 Advisory Council dedication to the success of the Program. We To make up for the faculty leaves, Jonathan 18 Faculty Research and News are all deeply indebted to her. Elukin from Trinity College, Hartford CT, filled in with a Jewish history course; Azzan 22 Events TIKvah FUND Yadin from Rutgers filled in for me with a One of the major achievements last year was course in Rabbinics; and Suzanne Last Stone a $4.5 million grant from the Tikvah Fund from the Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva incoming graduate students in Near Eastern for the Tikvah Project on Jewish Thought at University taught an American Jewish Stud- Studies, Religion, and Sociology, and we Princeton. -

Nationalism, Zionism, and the Forrnation of a National Narrative

CHAPTER ONE Nationalism, Zionism, and the Forrnation of a National Narrative Both the impulse which led to the creation of modern spoken Hebreu, and the circumstances which led to its successful establishment, are too unusual to set a general example. -E. J. Hobsbawm, Natlon s and Nationalism since 17 80 Hebrew in the Zionist lmaginary Modern theories of nationalism recognize that the origins and course of Zionism, the national movement of the Jewish people, are unusual if not unique among late-nineteenth-century national movements. Major thinkers have expressed their awareness of this singularity in terms that imply varying degrees of mystification. Ernest Gellner considers the State of Israel, the out- come of Zionism, "the most famous and dramatic case of a successful dias- pora nationalism," noting that "the human transformation involved in the Jewish case went counter to the global trend" (1983, 106-7). Gellner's choice of words such as dramatic and transformation to characterize the de- velopments that culminated in the founding of Israel intimates the scholarly consensus, which notes the peculiarity of the phenomenon without elaborat- ing on what makes it so. Benedict Anderson expresses his perplexity con- cerning Zionism in more striking language: "The significance of the emergence of Zionism and the birth of Israel is that the former marks the reimagining of an ancient religious community as a nation, down there among the other nations-while the latter charts an alchemic change from wandering devotee to local patriot" (1,991,149n. 16) Although it is curious that this enigmatic passage does not address-or 2 What Must Be Forgotten Formation of a National Narratiwe 3 even acknowledge-the causal connection between the two elements, Zion- ties sometimes totally isolated from each other. -

MYSTICISM in 20Th Century Hebrew Literature Israel: Society, Culture and History

MYSTICISM in 20th Century Hebrew Literature Israel: Society, Culture and History Yaacov Yadgar (Political Studies, Bar-Ilan University), Series Editor EDITORIAL BOARD Alan Dowty, Allan Silver, Political Science and Middle Eastern Sociology, Studies, University of Notre Dame Columbia University Tamar Katriel, Anthony D. Smith, Communication Ethnography, Nationalism and Ethnicity, University of Haifa London School of Economics Avi Sagi, Yael Zerubavel, Hermeneutics, Cultural studies, Jewish Studies and History, and Philosophy, Bar-Ilan University Rutgers University MYSTICISM in 20th Century Hebrew Literature Hamutal Bar-Yosef Boston 2010 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Copyright © 2010 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN: 978-1-936235-01-8 Book design by Olga Grabovsky Published by Academic Studies Press in 2010 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS PREFACE . 11 CHAPTER ONE Is Mysticism in Modern Hebrew Literature Possible? . .15 Secular Jewish Mysticism? • Mysticism and Literature • Literature in Traditional Jewish Mysticism • Modern Hebrew Literature • The Traces of Western Literature • Three Basic Elements • Identifying Mysticism in Modern Poetry CHAPTER TWO How did Mysticism Penetrate into Modern Hebrew Literature? . .53 Jewish Mysticism and the Haskalah Movement • Mysticism in 19th Century Russian Jewish Studies and Literature • The Romantic Stage • The Neo-Romantic Stage • Neo- Hassidic Hebrew Literature • The Russian Context, -

Grammar, Poetry, and Performance in the Work of Esther Raab Shoshana Olidort Stanford University

Subverting Hebrew’s Gender Binary: Grammar, Poetry, and Performance in the Work of Esther Raab Shoshana Olidort Stanford University abstract: This article examines antigrammaticality in the work of the so-called first “native” modern Hebrew poet, Esther Raab, focusing in particular on how Raab deploys the constraints of Hebrew’s highly gendered grammar in her poems. I begin by considering the broad implications of grammatical gender for how we think and act in the world, while also taking into account specific, concrete examples of gender policing that Raab recalled from her own early childhood. I then offer a close reading of a single, untitled poem to demonstrate how, from her position at the intersection of multiple margins, as a native-born female poet in a literary milieu dominated by immi- grants, most of them male, Raab effectively subverts both gender and grammar norms in the construction of a nonconforming gender identity. i like lines that are straight and strong,” the Hebrew poet Esther Raab (1894–1981) once said, while declaring her affinity for biblical Hebrew and the language of Bialik over that of her contemporaries.1 As she went on to explain: “I do not like things that are too “ complicated and that do not grow from a natural foundation: Earth, Water, Air, etc.”2 Scholarly readings of Raab’s work have tended to focus on the poet’s connection with the physical landscape of Eretz Yisrael, and images of the native (or, as it happens, imported) fauna and flora, the latter in particular, abound in Raab’s early work.