Talking Alone Reality TV, Emotions and Authenticity Minna Aslama University of Helsinki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teen Stabbing Questions Still Unanswered What Motivated 14-Year-Old Boy to Attack Family?

Save $86.25 with coupons in today’s paper Penn State holds The Kirby at 30 off late Honoring the Center’s charge rich history and its to beat Temple impact on the region SPORTS • 1C SPECIAL SECTION Sunday, September 18, 2016 BREAKING NEWS AT TIMESLEADER.COM '365/=[+<</M /88=C6@+83+sǍL Teen stabbing questions still unanswered What motivated 14-year-old boy to attack family? By Bill O’Boyle Sinoracki in the chest, causing Sinoracki’s wife, Bobbi Jo, 36, ,9,9C6/Ľ>37/=6/+./<L-97 his death. and the couple’s 17-year-old Investigators say Hocken- daughter. KINGSTON TWP. — Specu- berry, 14, of 145 S. Lehigh A preliminary hearing lation has been rampant since St. — located adjacent to the for Hockenberry, originally last Sunday when a 14-year-old Sinoracki home — entered 7 scheduled for Sept. 22, has boy entered his neighbors’ Orchard St. and stabbed three been continued at the request house in the middle of the day members of the Sinoracki fam- of his attorney, Frank Nocito. and stabbed three people, kill- According to the office of ing one. ily. Hockenberry is charged Magisterial District Justice Everyone connected to the James Tupper and Kingston case and the general public with homicide, aggravated assault, simple assault, reck- Township Police Chief Michael have been wondering what Moravec, the hearing will be lessly endangering another Photo courtesy of GoFundMe could have motivated the held at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 7 at person and burglary in connec- In this photo taken from the GoFundMe account page set up for the Sinoracki accused, Zachary Hocken- Tupper’s office, 11 Carverton family, David Sinoracki is shown with his wife, Bobbi Jo, and their three children, berry, to walk into a home on tion with the death of David Megan 17; Madison, 14; and David Jr., 11. -

Islands in the Screen: the Robinsonnade As Television Genre Des Îles À L’Écran : La Robinsonnade Comme Genre Télévisuel Paul Heyer

Document generated on 09/24/2021 6:24 p.m. Cinémas Revue d'études cinématographiques Journal of Film Studies Islands in the Screen: The Robinsonnade as Television Genre Des îles à l’écran : la robinsonnade comme genre télévisuel Paul Heyer Fictions télévisuelles : approches esthétiques Article abstract Volume 23, Number 2-3, Spring 2013 The island survivor narrative, or robinsonnade, has emerged as a small but significant television genre over the past 50 years. The author considers its URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1015187ar origins as a literary genre and the screen adaptations that followed. Emphasis DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1015187ar is placed on how “island TV” employed a television aesthetic that ranged from an earlier conventional approach, using three cameras, studio locations, and See table of contents narrative resolution in each episode, to open-ended storylines employing a cinematic style that exploits the new generation of widescreen televisions, especially with the advent of HDTV. Two case studies centre the argument: Gilligan’s Island as an example of the former, more conventional aesthetic, and Publisher(s) Lost as an example of the new approach. Although both series became Cinémas exceedingly popular, other notable programs are considered, two of which involved Canadian production teams: Swiss Family Robinson and The Mysterious Island. Finally, connections are drawn between robinsonnades and ISSN the emerging post-apocalyptic genre as it has moved from cinema to television. 1181-6945 (print) 1705-6500 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Heyer, P. (2013). Islands in the Screen: The Robinsonnade as Television Genre. Cinémas, 23(2-3), 121–143. -

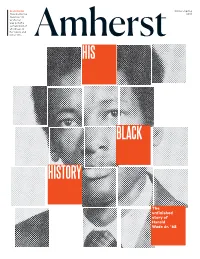

WEB Amherst Sp18.Pdf

ALSO INSIDE Winter–Spring How Catherine 2018 Newman ’90 wrote her way out of a certain kind of stuckness in her novel, and Amherst in her life. HIS BLACK HISTORY The unfinished story of Harold Wade Jr. ’68 XXIN THIS ISSUE: WINTER–SPRING 2018XX 20 30 36 His Black History Start Them Up In Them, We See Our Heartbeat THE STORY OF HAROLD YOUNG, AMHERST- WADE JR. ’68, AUTHOR OF EDUCATED FOR JULI BERWALD ’89, BLACK MEN OF AMHERST ENTREPRENEURS ARE JELLYFISH ARE A SOURCE OF AND NAMESAKE OF FINDING AND CREATING WONDER—AND A REMINDER AN ENDURING OPPORTUNITIES IN THE OF OUR ECOLOGICAL FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM RAPIDLY CHANGING RESPONSIBILITIES. BY KATHARINE CHINESE ECONOMY. INTERVIEW BY WHITTEMORE BY ANJIE ZHENG ’10 MARGARET STOHL ’89 42 Art For Everyone HOW 10 STUDENTS AND DOZENS OF VOTERS CHOSE THREE NEW WORKS FOR THE MEAD ART MUSEUM’S PERMANENT COLLECTION BY MARY ELIZABETH STRUNK Attorney, activist and author Junius Williams ’65 was the second Amherst alum to hold the fellowship named for Harold Wade Jr. ’68. Photograph by BETH PERKINS 2 “We aim to change the First Words reigning paradigm from Catherine Newman ’90 writes what she knows—and what she doesn’t. one of exploiting the 4 Amazon for its resources Voices to taking care of it.” Winning Olympic bronze, leaving Amherst to serve in Vietnam, using an X-ray generator and other Foster “Butch” Brown ’73, about his collaborative reminiscences from readers environmental work in the rainforest. PAGE 18 6 College Row XX ONLINE: AMHERST.EDU/MAGAZINE XX Support for fi rst-generation students, the physics of a Slinky, migration to News Video & Audio Montana and more Poet and activist Sonia Sanchez, In its interdisciplinary exploration 14 the fi rst African-American of the Trump Administration, an The Big Picture woman to serve on the Amherst Amherst course taught by Ilan A contest-winning photo faculty, returned to campus to Stavans held a Trump Point/ from snow-covered Kyoto give the keynote address at the Counterpoint Series featuring Dr. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Harsh Reality: When Producers and Networks Should Be Liable for Negligence and Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress

HSIOU_HARSH REALITY 1/31/2013 5:28 PM Harsh Reality: When Producers and Networks Should Be Liable for Negligence and Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress Melody Hsiou INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 188 I. BACKGROUND ........................................................................ 190 A. Review of Cases Addressing Tort Liability Claims against the Media .................................................... 193 II. NEGLIGENCE LAW AND REALITY TELEVISION ...................... 195 A. Employer-Employee Relationship ............................ 195 B. Special Relationships Based on Control .................. 204 III. INTENTIONAL INFLICTION OF EMOTIONAL DISTRESS .......... 210 A. Competition Format Reality Shows ......................... 212 B. Ambush Television: Talk Shows and Hidden Camera Shows ......................................................... 215 C. Documentary Style Reality Shows ........................... 217 IV. OBSTACLES ......................................................................... 218 V. CONCLUSION ....................................................................... 220 187 HSIOU_HARSH REALITY) 1/31/2013 5:28 PM 188 Seton Hall Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law [Vol. 23.1 INTRODUCTION Since its inception in the early 1990s, reality television has been linked to negative effects on participants’ safety, emotional health, and welfare. In August 2011, Russell Armstrong, a cast member of Bravo network’s popular television show The Real Housewives -

Copyright Protection of Formats in the European Single Market - the Definition of the Copyright Protected Work with Respect to Utilitarian Copyright Theories

Copyright Protection of Formats in the European Single Market - The definition of the copyright protected work with respect to utilitarian copyright theories Master thesis in the framework of the European Legal Informatics Study Program 2012/13 Institut für Rechtsinformatik Leibniz Universiät Hannover Supervisor: Dr. Malek Barudi Author: Maximilian von Grafenstein Table of Contents Abbreviations V Literature VI A. Introduction 1 I. Copyright between Culture Industry and Participatory aka. Remix Culture 1 II. Relevance of formats for the discussion about copyright 4 III. Definition of “formats” and other terms 7 IV. Utilitarian copyright theories as theoretical scale 8 V. Structure of the following discussion 10 B. Economics of format markets 12 I. Television formats between cost-benefit-ratio and risk minimization 12 II. Franchise and user participation within transmedia formats 14 III. Conclusion – From television to transmedia formats 18 C. European format markets under lacking legal certainty 19 I. European harmonization of 28 copyright regimes 19 1. Principle of territoriality 19 2. Horizontal harmonization of exploitation rights 21 3. No harmonization of the copyright protected work (and the adaptation right) 22 II. Opponent copyright protection of formats in the Netherlands and Germany 23 1. Copyright protection of formats in the Netherlands 23 a) Facts: “Survive!” vs. “Big Brother” 24 b) Reasoning: “Combination of elements” 24 2. No copyright protection of formats in Germany 26 a) Facts: “L’école des fans ” vs. “Kinderquatsch mit Michael” 26 b) Reasoning: “Fiction-model-dichotomy” 27 3. Comparing “combination of elements” and “fiction-model-dichotomy” 28 III. Conclusion – Effects on European format markets 29 D. Theoretical scale for balance of interests on format markets 33 I. -

A Call for Rethinking Cultural Studies

BEYOND CELEBRATION: A CALL FOR RETHINKING CULTURAL STUDIES Carolyn Lea A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2007 Committee: Dr. Ellen Berry, Advisor Dr. Nancy C. Patterson Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Donald McQuarie Dr. Ewart Skinner © 2007 Carolyn Lea All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Ellen Berry, Advisor This is a polemical dissertation which seeks to serve as an intervention into the theoretical debates and tensions within cultural studies. These debates, which have taken place over the last few decades, have centered on the populist bent within cultural studies, the turn away from the concerns of political economy, and the influence of French theories that emphasize signification, play, and relativism. At stake in these debates is our way of understanding the world and imagining it differently. I argue that the celebratory direction found in much of the work by cultural studies scholars in which resistance, subversion and transgression are located in all things popular has led to an expressivist politics which lacks explanatory power and is symptomatic of a loss of political will. This dissertation critiques three particular directions that exemplify the celebratory turn: claims regarding transgression; claims regarding audience activity; and celebratory accounts of consumption. Chapter one provides an exposition of the debates that have plagued cultural studies, laying the ground for later arguments. Chapter two provides an introduction to reality television which is enlisted as a cultural symptom through which to interrogate weaknesses in theoretical positions (in chapters three through five) adopted by cultural studies scholars and strengths in alternative theoretical legacies. -

*!3I8B0B-Aaefad! Som DN Gjort

FREDAG 19 APRIL 2019 ○ SVERIGES STÖRSTA MORGONTIDNING ○ GRUNDAD 1864 ○ PRIS 45 KRONOR Snart slutblossat på uteserveringar Funck Fredrik Foto: Ekonomi 19 Den 1 juli blir det förbjudet att röka på flera allmänna platser. Filippa Kronholm och Emma Meltzer tycker inte om den nya lagen. Robert Redfords sista roll. ”Den siste gentlemannen” är en charmerande gammaldags skälmhistoria | Kultur 44 Ödesmättat om droghandel. Maktspelets dödliga effekter i colombianska ”Birds of passage”. | Kultur 42–43 films Eric Zachanowich/Fox Foto: Carl Johan von Seth: Tio exempel på Det riktigt svåra möjligt brott Miljonregnet över dilemmat gäller av Trump i rapport inte skillnaden mel- Världen. I Rysslandsrapporten före detta politiker lan fattig och rik, som överlämnades till USA:s kon- utan gapet mellan gress på torsdagen tar den sär- skilde åklagaren Robert Mueller Stockholm och upp tio exempel på vad som skulle kunna vara övergrepp i rättssak. Inkomstgaranti. Så mycket har ledamöterna resten av landet. Därför kan han inte frikänna Do- nald Trump från att ha begått en kriminell handling, skriver han i fått efter att de lämnat riksdagen Ekonomi 20 rapporten. Sidorna 10–11 Nyheter. Över 100 före detta po- De förmånliga fallskärmarna litiker som lämnat riksdagen får har åter blivit aktuella efter att före SAS-piloter fortfarande helt eller delvis sin för- detta liberalen Emma Carlsson Löf- sörjning av riksdagen. Det visar en dahl meddelat att hon tänker sitta hotar strejka genomgång*!3I8B0B-aaefad! som DN gjort. kvar i riksdagen som politisk vilde efter påsk Systemet med inkomstgaranti tills hon fyller 50 år nästa höst. Då för riksdagsledamöter har mötts av Emma Carlsson Pär Axel får hon rätt till full inkomstgaranti Löfdahl Sahlberg hård kritik och 2013 ändrades sys- ända fram till pensions dagen. -

Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human

RECOMMENDED PRINCIPLES AND GUIDELINES ON HUMAN RIGHTS TRAFFICKING – COMMENTARY COMMENTARY RECOMMENDED PRINCIPLES AND GUIDELINES ON HUMAN RIGHTS AND HUMAN TRAFFICKING RECOMMENDED PRINCIPLES AND GUIDELINES ON HUMAN RIGHTS AND HUMAN TRAFFICKING COMMENTARY Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Palais des Nations CH 1211 Geneva 10 – Switzerland Telephone: +41.22.917 90 00 Fax: +41.22.917 90 08 www.ohchr.org RECOMMENDED PRINCIPLES AND GUIDELINES ON HUMAN RIGHTS AND HUMAN TRAFFICKING COMMENTARY New York and Geneva, 2010 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a figure indicates a reference to a United Nations document. HR/PUB/10/2 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.10.XIV.1 ISBN 978-92-1-154190-8 © 2010 United Nations All worldwide rights reserved CREDITS Artwork: “Leptir” by Jana Kohut, a survivor of human trafficking. FOREWORD Over the past decade, human trafficking has acknowledgement that trafficking is, first and moved from the margins to the mainstream of foremost, a violation of human rights. Trafficking international concern. During this period we and the practices with which it is associated, have witnessed the rapid development of a including slavery, sexual exploitation, child comprehensive legal framework that comprises labour, forced labour, debt bondage and international and regional treaties, as well as forced marriage, are themselves violations of a broad range of soft-law instruments relating the basic human rights to which all persons to trafficking. -

Dagkirurgisk Forum 2,2010

kirurgi er en uslåelig vei fram i mer faglige og helsepolitiske forhold til å kombinere mindre forhold. ressursbruk for de finansi- erende myndigheter med bedre kvalitet for pasienten. Nye DRG- satser på dag- Omvendt er det fortsatt med kirurgi: De styrende politiske en vis undring vi ser at fre- og helseadministrative myn- kvensen av en rekke dag- digheter har, som det framgikk kirurgiske prosedyrer er så for- av siste års vintermøte – fått skjellige i forhold til geografi seg en ordentlig utfordring: å også i Norge. NORDAF ser at balansere en overordnet - og i der er behov for inspirasjon og våre øyne naturligvis riktig deling av kompetanse for å satsning - på dagkirurgi, glim- fremme dagkirurgien – også i rende formulert av den davær- de kommende år. ende statssekretær: ’Fra døgn til dag’ med fullt gjennomslag Fokus på kvalitet, pasientsik- for sterkt reduserte DRG- taks- kerhet og dokumentasjon av ter på dagkirurgi. Ved uendret Leder dette i vår behandling vil case-mix og operasjonsakti- garantert økes i de kommende vitet var det forventet at de På tross av motgang med år. dagkirurgiske enheter landet reduserte DRG- satser og over måtte se i øynene at de omstrukturering i de dag- Det kan synes rart, men der er dagkirurgiske inntekter ville kirurgiske, historisk sett ikke stor etterspørsel etter dale markant. Så er også til- velfungerende miljøer, viser kompetansen og erfaringen - fellet for undertegnedes dere i dagkirurgien initiativ og faglig og ledelsesmessig - i det avdeling på Martina Hansens virkelyst. Utvikling i dag- dagkirurgiske miljø i Hospital, hvor første halvår kirurgiske teknikker, anestesi forbindelse med de omfattende viste en nedgang på ca. -

Character Agency and Impression Management Within the Narrative of Survivor: Samoa

Syracuse University SURFACE S.I. Newhouse School of Public Mass Communications - Dissertations Communications 2011 Performing the Self: Character Agency and Impression Management within the Narrative of Survivor: Samoa Carolyn Davis Hedges Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/com_etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Hedges, Carolyn Davis, "Performing the Self: Character Agency and Impression Management within the Narrative of Survivor: Samoa" (2011). Mass Communications - Dissertations. 85. https://surface.syr.edu/com_etd/85 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mass Communications - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This study used an in-depth textual analysis of the television show Survivor: Samoa to demonstrate that the unscripted characters of the program and shows like it have agency within the narrative. In addition to the 19th season of the Survivor series, the sample also included Jeff Probst’s (host and executive producer of the series) weekly blog for EntertainmentWeekly.com. Unlike most popular television narratives, the unscripted characters of Survivor: Samoa have the opportunity to tell their own story. This doctoral project was an in-depth analysis at how that authorial power was shared between the Producers of the show and the individual characters. The results of indicate there are three types of narrative agents that contributed to the storytelling process: the producers, the characters, and then a unique mix of the two. -

Contemporary Feminist Theories Author: Jackson, Stevi

cover next page > title: Contemporary Feminist Theories author: Jackson, Stevi. publisher: Edinburgh University Press isbn10 | asin: 0748606890 print isbn13: 9780748606894 ebook isbn13: 9780585123622 language: English subject Feminist theory. publication date: 1998 lcc: HQ1190.C667 1998eb ddc: 305.4 subject: Feminist theory. cover next page > < previous page page_iii next page > Page iii Contemporary Feminist Theories Edited by Stevi Jackson and Jackie Jones Edinburgh University Press < previous page page_iii next page > < previous page page_iv next page > Page iv © The contributors, 1998 Edinburgh University Press 22 George Square, Edinburgh Typeset in Baskerville and Futura by Norman Tilley Graphics, Northampton, and printed and bound in Finland by WSOY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 7486 0689 0 (paperback) ISBN 0 7486 1141 X (hardback) The right of the contributors to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. < previous page page_iv next page > < previous page page_v next page > Page v Contents 1 Thinking for Ourselves: An Introduction to Feminist Theorising Stevi Jackson And Jackie Jones 1 2 Feminist Social Theory Stevi Jackson 12 3 Feminist Theory and Economic Change Lisa Adkins 34 4 Feminist Political Theory Elizabeth Frazer 50 5 Feminist Jurisprudence Jane Scoular 62 6 Feminism and Anthropology Penelope Harvey 73 7 Black Feminisms Kadiatu Kanneh 86 8 Post-colonial Feminist Theory Sara Mills 98 9 Lesbian Theory