This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reimagining Chinese Indonesians in Democratic Indonesia

Asia Pacific Bulletin Number 109 | May 10, 2011 Reimagining Chinese Indonesians in Democratic Indonesia BY RAY HERVANDI Indonesia’s initiation of democratic reforms in May 1998 did not portend well for Chinese Indonesians. Constituting less than 5 percent of Indonesia’s 240 million people and concentrated in urban areas, Chinese Indonesians were, at that point, still reeling from the anti-Chinese riots that had occurred just before Suharto’s fall. Scarred by years of discrimination and forced assimilation under Suharto, many Chinese Indonesians were uncertain—once again—about what the “new” Indonesia had in store for them. Yet, the transition to an open Indonesia has also resulted in greater space to be Chinese Indonesian. Laws and regulations discriminating against Chinese Indonesians have been Ray Hervandi, Project Assistant at repealed. Chinese culture has grown visible in Indonesia. Mandarin Chinese, rarely the the East-West Center in language of this minority in the past, evolved into a novel emblem of Chinese Washington, argues that Indonesians’ public identity. Indonesians need to “restart a civil Notwithstanding the considerably expanded tolerance post-Suharto Indonesia has conversation that examines how shown Chinese Indonesians, their delicate integration into Indonesian society is a work [Chinese Indonesians fit] in in progress. Failure to foster full integration would condemn Chinese Indonesians to a continued precarious existence in Indonesia and leave them vulnerable to violence at the Indonesia’s ongoing state- and next treacherous turning point in Indonesian politics. This undermines Indonesia’s nation-building project. In the ideals that celebrate the ethnic, religious, and cultural pluralism of all its citizens. -

Only Believe Song Book from the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, Write To

SONGS OF WORSHIP Sung by William Marrion Branham Only Believe SONGS SUNG BY WILLIAM MARRION BRANHAM Songs of Worship Most of the songs contained in this book were sung by Brother Branham as he taught us to worship the Lord Jesus in Spirit and Truth. This book is distributed free of charge by the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, with the prayer that it will help us to worship and praise the Lord Jesus Christ. To order the Only Believe song book from the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, write to: Spoken Word Publications P.O. Box 888 Jeffersonville, Indiana, U..S.A. 47130 Special Notice This electronic duplication of the Song Book has been put together by the Grand Rapids Tabernacle for the benefit of brothers and sisters around the world who want to replace a worn song book or simply desire to have extra copies. FOREWARD The first place, if you want Scripture, the people are supposed to come to the house of God for one purpose, that is, to worship, to sing songs, and to worship God. That’s the way God expects it. QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS, January 3, 1954, paragraph 111. There’s something about those old-fashioned songs, the old-time hymns. I’d rather have them than all these new worldly songs put in, that is in Christian churches. HEBREWS, CHAPTER SIX, September 8, 1957, paragraph 449. I tell you, I really like singing. DOOR TO THE HEART, November 25, 1959. Oh, my! Don’t you feel good? Think, friends, this is Pentecost, worship. This is Pentecost. Let’s clap our hands and sing it. -

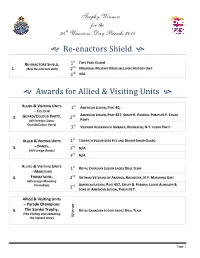

Re-Enactors Shield Awards for Allied & Visiting Units

Trophy Winners for the 94th Warriors’ Day Parade 2015 Re-enactors Shield st Fort York Guard RE-ENACTORS SHIELD, 1 nd 1. (Best Re-enactors Unit) 2 MEMORIAL MILITARY MUSEUM LIVING HISTORY UNIT 3rd N/A Awards for Allied & Visiting Units ALLIED & VISITING UNITS st 1 AMERICAN LEGION, POST 40, – COLOUR AMERICAN LEGION, POST 457, SEELEY B. PARRISH, PHELPS N.Y. COLOR 2. GUARD/COLOUR PARTY, 2nd (All Foreign Colour PARTY Guards/Colour Party) rd VIETNAM VETERANS OF AMERICA, ROCHESTER, N.Y. COLOR PARTY 3 st ALLIED & VISITING UNITS 1 TOWPATH VOLUNTEERS FIFE AND DRUM HONOR GUARD – BANDS, nd 3. 2 N/A (All Foreign Bands) 3rd N/A ALLIED & VISITING UNITS st 1 ROYAL CANADIAN LEGION LADIES DRILL TEAM – MARCHING nd 4. FORMATIONS, 2 VIETNAM VETERANS OF AMERICA, ROCHESTER, N.Y. MARCHING UNIT (All Foreign Marching AMERICAN LEGION, POST 457, SEELEY B. PARRISH, LADIES AUXILIARY & Formation) 3rd SONS OF AMERICAN LEGION, PHELPS N.Y. Allied & Visiting Units – Parade Champions 5. The Samko Trophy, ROYAL CANADIAN LEGION LADIES DRILL TEAM (The Visiting Unit obtaining the highest score) Winner Page 1 Trophy Winners for the 94th Warriors’ Day Parade 2015 Awards for Non-Veteran Units in Canada st The Molson Trophy, 1 DERRY FLUTE BAND (Flute, Fife, Accordion & Drum nd ULSTER ACCORDION BAND 6. Band) 2 rd 3 N/A The LCol, The st 1 32 CANADIAN BRIGADE GROUP Honourable J. Keiller MacKay Memorial nd 7. Trophy and Plaque 2 N/A (CAF Regular & Reserve Marching Formations) 3rd N/A Awards for Canadian Veteran Units st The Canon Scott 1 ROYAL REGIMENT OF CANADA ASSOCIATION Trophy, ROYAL CANADIAN LEGION, DISTRICT E, ONTARIO COMMAND, MARCHING 8. -

Bickers, Thesis 1992

Bickers, R. (1992). Changing British Attitudes to China and the Chinese, 1928-1931: Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document Copyright Robert Bickers, 1992 University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Changing British Attitudes to China and the Chinese, 1928-1931 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosphy Robert A. Bickers School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 1992 Copyright 1992 Robert Bickers Abstract This study examines the context and nature of British attitudes to China and the Chinese in the period 1928 to 1931, between the initial consolidation of the Nationalist Revolution in China and the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. The relationship between official and popular levels of this discourse provides the dominant theme of this work. It is argued that these years saw the start of a major long-term shift in British attitudes prompted by the Nationalist Revolution and by changes in Britain's official policy towards China. A wide range of official, institutional, and private primary and secondary material relating to Sino-British relations and to British treaty port life in China is examined in order to identify the sources, nature, and influence of British attitudes. -

© 2013 Yi-Ling Lin

© 2013 Yi-ling Lin CULTURAL ENGAGEMENT IN MISSIONARY CHINA: AMERICAN MISSIONARY NOVELS 1880-1930 BY YI-LING LIN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral committee: Professor Waïl S. Hassan, Chair Professor Emeritus Leon Chai, Director of Research Professor Emeritus Michael Palencia-Roth Associate Professor Robert Tierney Associate Professor Gar y G. Xu Associate Professor Rania Huntington, University of Wisconsin at Madison Abstract From a comparative standpoint, the American Protestant missionary enterprise in China was built on a paradox in cross-cultural encounters. In order to convert the Chinese—whose religion they rejected—American missionaries adopted strategies of assimilation (e.g. learning Chinese and associating with the Chinese) to facilitate their work. My dissertation explores how American Protestant missionaries negotiated the rejection-assimilation paradox involved in their missionary work and forged a cultural identification with China in their English novels set in China between the late Qing and 1930. I argue that the missionaries’ novelistic expression of that identification was influenced by many factors: their targeted audience, their motives, their work, and their perceptions of the missionary enterprise, cultural difference, and their own missionary identity. Hence, missionary novels may not necessarily be about conversion, the missionaries’ primary objective but one that suggests their resistance to Chinese culture, or at least its religion. Instead, the missionary novels I study culminate in a non-conversion theme that problematizes the possibility of cultural assimilation and identification over ineradicable racial and cultural differences. -

Mutual Integration Versus Forced Assimilation

Mutual Integration Versus Forced Assimilation: The Conflict between Sandinistas and Miskitu Indians, 1979-1987 by Jordan Taylor Towne An honors thesis submitted to the Honors Committee of The University of Colorado at Boulder Spring 2013 Abstract: This study aims to i) disentangle the white man’s overt tendency of denigrating indigenous agency to ethnic identity and, through the narrative of the Miskitu people of Nicaragua’s Atlantic Coast, display that this frequent ethnic categorization oversimplifies a complex cultural identity; ii) bring to the fore the heterogeneity inherent to even the most seemingly unanimous ethnic groups; iii) illustrate the influence of contingent events in shaping the course of history; and iv) demonstrate that without individuals, history would be nonexistent—in other words, individuals matter. Through relaying the story of the Miskitu Indians in their violent resistance against the Revolutionary Sandinistas, I respond contrarily to some of the relevant literature’s widely held assumptions regarding Miskitu homogeneity, aspirations, and identity. This is achieved through chronicling the period leading to war, the conflict itself, and the long return to peace and respectively analyzing the Miskitu reasons for collective resistance, their motives in supporting either side of the fragmented leadership, and their ultimate decision to lay down arms. It argues that ethnic identity played a minimal role in escalating the Miskitu resistance, that the broader movement did not always align ideologically with its representative bodies throughout, and that the Miskitu proved more heterogeneous as a group than typically accredited. Accordingly, specific, and often contingent events provided all the necessary ideological premises for the Miskitu call to arms by threatening their culture and autonomy—the indispensible facets of their willingness to comply with the central government—thus prompting a non-revolutionary grassroots movement which aimed at assuring the ability to join the revolution on their own terms. -

BUZZ Newsletter January

January 2015 ANAF Unit #68 “The Friendly Club” Volume 206 THE BUZZ and liberated our country. My father was then sent to Indonesia, a Dutch colony at YOUR the time, who were fighting for PRESIDENT’S their Independence, and he did not return REPORT for 4 years. I was 5 years old when we were finally re-united. "HAPPY 2015" Comrades! After the war ended my dad said "Canada is where we are going" so in 1951 we arrived in Quebec City and moved to It is no coincidence that when you get this Niagara Falls, Ontario, where my 93 year month’s Buzz I will have celebrated my old mother still resides. 70th birthday. It has also been 70 years since World War II. Therefore I thought I Today in Holland, school children age 6, would share a true personal story. I was are assigned a gravestone at a Canadian born, January 7, 1945 in Holland. I was Cemetery. They must learn all they can born 6 weeks pre-mature, weighing only 2 about the soldiers name on the grave and lbs 8 ozs. Since it was only 6 months after clean and look after their soldier's grave D-Day, a lot of people think that the war until they leave elementary school ended in 1945 but believe me it did not. and then another 6 year old is given the task. This remembrance and respect will As the Germans knew they were losing the go on forever. war in Europe they were extremely cruel; there was no food, water or any utilities The Dutch people will never forget the and my father, who was a Lieutenant in the contribution and sacrifices made by our Dutch army, had to go underground. -

Somaliland: a Model for Greater Liat Krawczyk Somalia?

JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL SERVICE VOLUME 21 | NUMBER 1 | SPRING 2012 i Letter from the Editor Maanasa K. Reddy 1 Women’s Political Participation in Sub- Anna-Kristina Fox Saharan Africa: Producing Policy That Is Important to Women and Gender Parity? 21 Russia and Cultural Production Under Alina Shlyapochnik Consumer Capitalism 35 Somaliland: A Model for Greater Liat Krawczyk Somalia? 51 Regulatory Convergence and North Inu Barbee American Integration: Lessons from the European Single Market 75 Elite Capture or Capturing the Elite? The Ana De Paiva Political Dynamics Behind Community- Driven Development 85 America’s Silent Warfare in Pakistan: An Annie Lynn Janus Analysis of Obama’s Drone Policy 103 Asia as a Law and Development Exception: Does Indonesia Fit the Mold? Jesse Roberts 119 Islamic Roots of Feminism in Egypt and Shreen A. Khan Morocco Knut Fournier Letter from the Editor Maanasa K. Reddy Dear Reader, Many of my predecessors have lamented the Journal’s lack of thematic coherence; I believe that this, the 20th Anniversary, issue has taken a step forward. The first and last articles of the issue discuss gender and feminism, which you may point out isn’t really thematic coherence. This is true; however, I am proud to present a Journal comprised of eight articles, written by eight incredibly talented female authors and one equally talented male co-author on a variety of international service issues. The Journal receives many submissions for every issue with about a 45/55 split from males and females respectively, according to data from the past three years of submissions. The selection process is blind, with respect to identity and gender, and all selections are based on the merits of the writing and relevance of the content. -

WALLACE, (Richard Horatio) Edgar Geboren: Greenwich, Londen, 1 April 1875

WALLACE, (Richard Horatio) Edgar Geboren: Greenwich, Londen, 1 april 1875. Overleden: Hollywood, USA, 10 februari 1932 Opleiding: St. Peter's School, Londen; kostschool, Camberwell, Londen, tot 12 jarige leeftijd. Carrière: Wallace was de onwettige zoon van een acteur, werd geadopteerd door een viskruier en ging op 12-jarige leeftijd van huis weg; werkte bij een drukkerij, in een schoen- winkel, rubberfabriek, als zeeman, stukadoor, melkbezorger, in Londen, 1886-1891; corres- pondent, Reuter's, Zuid Afrika, 1899-1902; correspondent, Zuid Afrika, London Daily Mail, 1900-1902 redacteur, Rand Daily News, Johannesburg, 1902-1903; keerde naar Londen terug: journalist, Daily Mail, 1903-1907 en Standard, 1910; redacteur paardenraces en later redacteur The Week-End, The Week-End Racing Supplement, 1910-1912; redacteur paardenraces en speciaal journalist, Evening News, 1910-1912; oprichter van de bladen voor paardenraces Bibury's Weekly en R.E. Walton's Weekly, redacteur, Ideas en The Story Journal, 1913; schrijver en later redacteur, Town Topics, 1913-1916; schreef regelmatig bijdragen voor de Birmingham Post, Thomson's Weekly News, Dundee; paardenraces columnist, The Star, 1927-1932, Daily Mail, 1930-1932; toneelcriticus, Morning Post, 1928; oprichter, The Bucks Mail, 1930; redacteur, Sunday News, 1931; voorzitter van de raad van directeuren en filmschrijver/regisseur, British Lion Film Corporation. Militaire dienst: Royal West Regiment, Engeland, 1893-1896; Medical Staff Corps, Zuid Afrika, 1896-1899; kocht zijn ontslag af in 1899; diende bij de Lincoln's Inn afdeling van de Special Constabulary en als speciaal ondervrager voor het War Office, gedurende de Eerste Wereldoorlog. Lid van: Press Club, Londen (voorzitter, 1923-1924). Familie: getrouwd met 1. -

Honour Guard Free

FREE HONOUR GUARD PDF Dan Abnett | 416 pages | 20 Oct 2015 | GAMES WORKSHOP | 9781784960049 | English | United States Honor Guard | Definition of Honor Guard by Merriam-Webster A guard of honour GBalso honor Honour Guard USalso ceremonial guardis a guard, usually military in nature, appointed to receive or guard a head of state or other dignitaries, the fallen in war, or to attend at state ceremonials, especially funerals. In military weddings, especially those of commissioned officers, a guard, composed usually of service members of the same branch, form the Saber arch. In principle any military unit could act as a guard of honour. However, in some countries certain units are specially designated to serve as a guard of honour, as well as other public duties. Guards of Honour also serve in the civilian world for fallen police officers and other civil servants. Certain religious bodies, especially Churches of Honour Guard Anglican Communion and the Methodist movement, have the tradition of an Honour Guard Honour Guard the funeral of an ordained elder, in which all other ordained elders present "guard the line" between the door of the church and the grave, or hearse if the deceased is to be buried elsewhere or cremated. Guards of honour have been mounted by a number of military forces, uniformed paramilitary organizations, and civilian emergency services. Composed of Honour Guard, troops, it is very similar in its formation style to equivalent units in the French Army. The Republican Guard includes a military band and a cavalry unit, the uniform and traditions of which Honour Guard based on those of the famous Berber cavalry, the Numidian cavalrythe French cavalry, and the Arab cavalry, as well as infantry. -

Media Industry Approaches to Comic-To-Live-Action Adaptations and Race

From Serials to Blockbusters: Media Industry Approaches to Comic-to-Live-Action Adaptations and Race by Kathryn M. Frank A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Lisa A. Nakamura Associate Professor Aswin Punathambekar © Kathryn M. Frank 2015 “I don't remember when exactly I read my first comic book, but I do remember exactly how liberated and subversive I felt as a result.” ― Edward W. Said, Palestine For Mom and Dad, who taught me to be my own hero ii Acknowledgements There are so many people without whom this project would never have been possible. First and foremost, my parents, Paul and MaryAnn Frank, who never blinked when I told them I wanted to move half way across the country to read comic books for a living. Their unending support has taken many forms, from late-night pep talks and airport pick-ups to rides to Comic-Con at 3 am and listening to a comics nerd blather on for hours about why Man of Steel was so terrible. I could never hope to repay the patience, love, and trust they have given me throughout the years, but hopefully fewer midnight conversations about my dissertation will be a good start. Amanda Lotz has shown unwavering interest and support for me and for my work since before we were formally advisor and advisee, and her insight, feedback, and attention to detail kept me invested in my own work, even in times when my resolve to continue writing was flagging. -

Legal Mediators: British Consuls in Tengyue (Western Yunnan) and the Burma-China Frontier Region, –

Modern Asian Studies , () pp. –. © The Author . This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/./), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the same Creative Commons licence is included and the original work is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use. doi:./SXX First published online August Legal Mediators: British consuls in Tengyue (western Yunnan) and the Burma-China frontier region, – EMILY WHEWELL Max Planck Institute for European Legal History Email: [email protected] Abstract British consuls were key agents for the British imperial presence in China from to . Their role, which was to perform administrative duties that protected the rights of British subjects, is most prominently remembered in connection with the east coast. Here larger foreign communities and international maritime trade necessitated their presence. However, British consuls were also posted to the far southwest province of Yunnan and the Burma-China frontier region. This article sheds light on the role of consuls working in the little-known British consular station of Tengyue, situated close to the Burma-China frontier. Using the reports of locally stationed consuls and Burmese frontier officials, it argues that consuls were important mediators of legal power operating at the fringes of empire for British imperial and colonial interests in this region. They represented British and European subjects, and were mediators in legal disputes between British Burma and China, helping to smooth over Sino- British relations and promoting British Burmese sovereign interests.