Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER XXX. of Fallacies. Section 827. After Examining the Conditions on Which Correct Thoughts Depend, It Is Expedient to Clas

CHAPTER XXX. Of Fallacies. Section 827. After examining the conditions on which correct thoughts depend, it is expedient to classify some of the most familiar forms of error. It is by the treatment of the Fallacies that logic chiefly vindicates its claim to be considered a practical rather than a speculative science. To explain and give a name to fallacies is like setting up so many sign-posts on the various turns which it is possible to take off the road of truth. Section 828. By a fallacy is meant a piece of reasoning which appears to establish a conclusion without really doing so. The term applies both to the legitimate deduction of a conclusion from false premisses and to the illegitimate deduction of a conclusion from any premisses. There are errors incidental to conception and judgement, which might well be brought under the name; but the fallacies with which we shall concern ourselves are confined to errors connected with inference. Section 829. When any inference leads to a false conclusion, the error may have arisen either in the thought itself or in the signs by which the thought is conveyed. The main sources of fallacy then are confined to two-- (1) thought, (2) language. Section 830. This is the basis of Aristotle's division of fallacies, which has not yet been superseded. Fallacies, according to him, are either in the language or outside of it. Outside of language there is no source of error but thought. For things themselves do not deceive us, but error arises owing to a misinterpretation of things by the mind. -

Empedocles: Neurophilosophy and Neurosciences- Prophecy and Reality

Journal of Neurology & Stroke Empedocles: Neurophilosophy and Neurosciences- Prophecy and Reality Keywords Editorial Volume 1 Issue 6 - 2014 Empedocles; Neurosciences; Neurophilosophy; Mitochondria; Limbic system; Amygdala Stavros J. Baloyannis* Editorial Aristotelian University, Greece *Corresponding author: Neurosciences are extended into a broad field, where the Stavros J. Baloyannis, Department scientific observation and research join harmoniously the of Emeritus, Aristotelian University, Thessaloniki, Angelaki 5, Greece,Received: Tel: +302310270434; Email:| Published: imagination, the intuition, the philosophy, the critic analysis, 2014 the enthusiasm and the skepticism, opening new horizons in the October 01, 2014 October 06, Fromtheoretic the perspectivesEra of Pre-Socratic and offering philosophers, new motivations soul and for mind research, have on the bases of an advanced multi-dimensional intellectuality. meditation [1]. Questions that the human being posed to himself, emotions, the feelings and the social behavior of the human being. been the subject of continuous speculation, study, research and soul in order to discover the interior power which motivates the concerning the existence, the soul, the psychosomatic entity, the regulatesHe tried to and identify controls the mainall the pivots spectrum of the of emotional the human interactions. emotions. cognition, the knowledge of the world, and the perception of time He insisted that Love and Strife are the ends of an axis, which and space used to exercise always an existential anxiety. According to Empedocles there is not birth or coming into Very frequently, human emotions have been the foci of existence and death. There is only a connection or mixture and insisting endeavors for right interpretation and detailed analysis. separation of four pure fundamental elements or “roots”, which Reasonably, the importance of the mental activities and interior are “the earth”, “the air”, “the fire” and “the water”. -

The Unity of Heidegger's Project

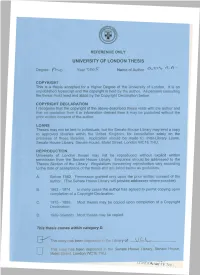

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree fV\o Year Too£ Name of Author A-A COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962- 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D. -

Predeterminism and Moral Agency in the Hodayot

Predeterminism and Moral Agency in the Hodayot Carol A. Newsom 1 Introduction For reasons that are not yet entirely clear, sharp disagreements about pre- determinism and free will became a significant feature of Jewish theological stances in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Josephus provides the most ex- plicit consideration of these issues in ancient Jewish sources, as he attempts to distinguish the positions of the three major Jewish sects with respect to the philosophical category of “fate” (εἱμαρμένη). Josephus identifies the position of the Essenes as believing strongly in fate, to the apparent exclusion of free will (Ant. 13.172). Similarly, modern scholarly treatments of the Qumran yaḥad have acknowledged the very strong predeterminist element in their thinking, attested in a variety of sectarian or closely related texts.1 At the same time, there has been a degree of perplexity as to what to do with the obviously volun- tarist statements and assumptions that are present in these same documents. A variety of suggestions have been made, mostly to the effect that the sectar- ians were inconsistent or not fully systematic in their beliefs.2 This may in- deed be the case, though Jonathan Klawans argues that, properly understood, all deterministic systems are consistent with voluntarism in a rather minimal 1 I take the Qumran yaḥad movement to be Essene, though I consider it possible that the term “Essene” may also have referred to groups not formally part of the yaḥad. For examinations of the phenomenon of predestination in Qumran sectarian literature and closely related texts, see J. Licht, “The Concept of Free Will in the Writings of the Sect of the Judean Desert,” in Studies in the Dead Sea Scrolls: Lectures Delivered at the Third Annual Conference (1957) in Memory of E. -

18 Free Ways to Download Any Video Off the Internet Posted on October 2, 2007 by Aseem Kishore Ads by Google

http://www.makeuseof.com/tag/18-free-ways-to-download-any-video-off-the-internet/ 18 Free Ways To Download Any Video off the Internet posted on October 2, 2007 by Aseem Kishore Ads by Google Download Videos Now download.cnet.com Get RealPlayer® & Download Videos from the web. 100% Secure Download. Full Movies For Free www.YouTube.com/BoxOffice Watch Full Length Movies on YouTube Box Office. Absolutely Free! HD Video Players from US www.20north.com/ Coby, TV, WD live, TiVo and more. Shipped from US to India Video Downloading www.VideoScavenger.com 100s of Video Clips with 1 Toolbar. Download Video Scavenger Today! It seems like everyone these days is downloading, watching, and sharing videos from video-sharing sites like YouTube, Google Video, MetaCafe, DailyMotion, Veoh, Break, and a ton of other similar sites. Whether you want to watch the video on your iPod while working out, insert it into a PowerPoint presentation to add some spice, or simply download a video before it’s removed, it’s quite essential to know how to download, convert, and play these videos. There are basically two ways to download videos off the Internet and that’s how I’ll split up this post: either via a web app or via a desktop application. Personally, I like the web applications better simply because you don’t have to clutter up and slow down your computer with all kinds of software! UPDATE: MakeUseOf put together an excellent list of the best websites for watching movies, TV shows, documentaries and standups online. -

From Hades to the Stars: Empedocles on the Cosmic Habitats of Soul', Classical Antiquity, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer From Hades to the stars Citation for published version: Trepanier, S 2017, 'From Hades to the stars: Empedocles on the cosmic habitats of soul', Classical Antiquity, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 130-182. https://doi.org/10.1525/ca.2017.36.1.130 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1525/ca.2017.36.1.130 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Classical Antiquity Publisher Rights Statement: Published as Trépanier, S. 2017. From Hades to the Stars: Empedocles on the Cosmic Habitats of Soul, Classical Antiquity, Vol. 36 No. 1, April 2017; (pp. 130-182) DOI: 10.1525/ca.2017.36.1.130. © 2017 by the Regents of the University of California. Authorization to copy this content beyond fair use (as specified in Sections 107 and 108 of the U. S. Copyright Law) for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by the Regents of the University of California for libraries and other users, provided that they are registered with and pay the specified fee via Rightslink® or directly with the Copyright Clearance Center. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. -

Release 3.5.3

Ex Falso / Quod Libet Release 3.5.3 February 02, 2016 Contents 1 Table of Contents 3 i ii Ex Falso / Quod Libet, Release 3.5.3 Note: There exists a newer version of this page and the content below may be outdated. See https://quodlibet.readthedocs.org/en/latest for the latest documentation. Quod Libet is a GTK+-based audio player written in Python, using the Mutagen tagging library. It’s designed around the idea that you know how to organize your music better than we do. It lets you make playlists based on regular expressions (don’t worry, regular searches work too). It lets you display and edit any tags you want in the file, for all the file formats it supports. Unlike some, Quod Libet will scale to libraries with tens of thousands of songs. It also supports most of the features you’d expect from a modern media player: Unicode support, advanced tag editing, Replay Gain, podcasts & Internet radio, album art support and all major audio formats - see the screenshots. Ex Falso is a program that uses the same tag editing back-end as Quod Libet, but isn’t connected to an audio player. If you’re perfectly happy with your favorite player and just want something that can handle tagging, Ex Falso is for you. Contents 1 Ex Falso / Quod Libet, Release 3.5.3 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 Table of Contents Note: There exists a newer version of this page and the content below may be outdated. See https://quodlibet.readthedocs.org/en/latest for the latest documentation. -

Spectacular Pregnancies / Monstrous Pregnancies As Represented in Three Pliegos Sueltos Poéticos Stacey L

University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well Spanish Publications Faculty and Staff choS larship Fall 2016 Spectacular Pregnancies / Monstrous Pregnancies As Represented In Three Pliegos Sueltos Poéticos Stacey L. Parker Aronson University of Minnesota - Morris Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/span_facpubs Part of the Spanish Literature Commons Recommended Citation Parker Aronson, Stacey L. "Spectacular Pregnancies / Monstrous Pregnancies As Represented In Three Pliegos Sueltos Poéticos." Hispanic Journal, v.37, no. 2, 2016, pp. 2-11. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Staff choS larship at University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spanish Publications by an authorized administrator of University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spectacular Pregnancies / Monstrous Pregnancies As Represented In Three Pliegos Sueltos Poéticos Stacey L. Parker Aronson University of Minnesota, Morris “For as St Paul says, every sin that is committed is outside the body except this one alone. All the other sins are only sins; but this is a sin, and also disfigures you and dishonours your body, … [you] do harm to yourself, mistreating yourself quite voluntarily in such a shameful way.” (31) —“Hali Meiðhad / A Letter on Virginity for the Encouragement of Virgins” (1190-1230?) “The grotesque body, … is a body in the act of becoming. It is never finished, never completed; it is continually built, created, and builds and creates another body.” (317) —Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World (1965) In this age of advancements in procreative technologies that have increased the incidence of multiple births, we are at times fascinated and at others repulsed by these reproductive results. -

Colker, Marvin L./ Analecta Dublinensia: Three Mediaeval Latin

THE MEDIAEVAL ACADEMY OF AMERICA PUBLICATION NO. 82 ANALECTA DVBLINENSIA ANALECTA DVBLINENSIA THREE MEDIEVAL LATIN TEXTS IN THE LIBRARY OF TRINITY COLLEGE DUBLIN edited by MARVIN L. COLKER The University of Virginia THE MEDIAEVAL ACADEMY OF AMERICA CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 1975 The publication of this book was made possible by grants of funds to the Mediaeval Academy from the Carnegie Corporation of New York Copyright ©1975 By The Mediaeval Academy of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-1954 ISBN 910956-56-1 Printed in the United States of America To Philip Ian Colker This Book Is Dedicated Contents Preface 1 1. CONTRA RELIGIONIS SIMVLATORES Introduction 5 Summary 9 Text 17 Notes 52 Index Nominum 59 Index Rerum Memorabilium 60 Index Auctorum et Operum Romanorum ac Medii Aeui Citatorum 62 2. EPISTOLAE AD AMICVM AND THREE POEMS Introduction 65 Summary 75 Text 91 Appendices 161 & 162 Notes 164 Index Nominum 173 Index Rerum Memorabilium 174 Index Verborum uel Significationum Inusitatiorum 177 Index Auctorum et Operum Romanorum ac Medii Aeui Citatorum 178 CONTENTS 3. A COLLECTION OF STORIES AND SKETCHES: PETRONIVS REDIVIVVS Introduction 181 Summary 189 Text 195 Notes 236 Index Nominum 253 Index Rerum Memorabilium 254 Index Verborum uel Significationum Inusitatiorum 256 Index Auctorum et Operum Romanorum ac Medii Aeui Citatorum 257 Preface OVER the past decade I have been privileged to work on the re-cataloging of the medieval Latin manuscripts at Trinity College Dublin. In the course of this effort, I came upon three unpublished -

Nöroetik Prensipler 5

Türk Dünyası Uygulama ve Araştırma Merkezi Sinir Bilim Dergisi No. 2018/1-2 B ö l ü m Nöroetik Prensipler 5 Etik ilkeler konusunda öneriler Etiksel kavramları daha somut boyuta getirerek prensiplerin ilkeleştirilmesi hedeflenmiştir. öroetik konusunda etiksel anlamda ilkeleşme, tüm insanı ve insanlığı kapsadığı için, tüm etik ilkeleri bünyesinde toplamaktadır. N Nöroetik olarak konunun yeniden gözden geçirilmesi ve ilkeleştirilmesi yukarıdaki kapsam altında gerekli olmadığı anlaşılacaktır. Ancak, olayın özetlenmesi açısından ilkelerde toparlamanın mümkün olabileceği varsayılmaktadır. Her bir yaklaşımda belirli esasların oluşturulması önceliklidir. Bir konu ele alınırken, o konuda bilgi sorgulaması öncesinde, belirli bir planın yapılması gerekir. Planlama olmadan rastgele alınan bilgiler, belirli bir bilgi kirliliğine neden olabilecektir. Birbiri ile çelişen durumlar ve bilgileri çözmek imkansızlaştığı gibi, belirli sorunlara da neden olabilecektir. Bu açıdan nöroetik kavramı üzerinde değinilmeden önce, bu konuda temel yaklaşımlar, belirli bir felsefe içinde ele alınmasını gerekli kılmaktadır. Öncelikle konuyu ele alma biçimi, olayı yrumlama ve algılama düzeyi ortaya konulmalıdır. Bu amaçla nöroetik konusunda bir genel yaklaşım esasları oluşturulmaya çalışılmıştır. Aşağıda bir ilkeleme çalışması görülecektir. Nöroetik Prensipler/İlkeler TANIMLAMALAR Etik Tıp Bilimi temelde insanı birey olarak ele almakta ve onun haklarının öncelikli olduğu ve otonomisinin her türlü durumda korunmasının hukuksal açıdan da ilke olarak ele alınması gerektiğinin bilincindedir. Sayfa. 252 Türk Dünyası Uygulama ve Araştırma Merkezi Sinir Bilim Dergisi No. 2018/1-2 Birey, insan olmanın gerektiği modelinde, ruhsal, sosyal ve kültürel anlamda da toplumsal bir kişiliği olduğunun kavramı olarak da algılanmalıdır. Hekimlik mesleği, bireyin özerkliği ve kendi haklarını belirleme çerçevesinde, tıp biliminin uygulanması yanında sanatsal ve felsefe bilimler anlamında da bir bütünlüğü gerekli kılmaktadır. Tüm diğer özellikler hukuksal esaslar yanında etik ilkeler boyutunda da olmalıdır. -

Thomas Aquinas' Metaphysics of Creatio Ex Nihilo

Studia Gilsoniana 5:1 (January–March 2016): 217–268 | ISSN 2300–0066 Andrzej Maryniarczyk, S.D.B. John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin Poland PHILOSOPHICAL CREATIONISM: THOMAS AQUINAS’ METAPHYSICS OF CREATIO EX NIHILO In keeping with the prevalent philosophical tradition, all philoso- phers, beginning with the pre-Socratics, through Plato and Aristotle, and up to Thomas Aquinas, accepted as a certain that the world as a whole existed eternally. They supposed that only the shapes of particu- lar things underwent transformation. The foundation for the eternity of the world was the indestructible and eternal primal building material of the world, a material that existed in the form of primordial material elements (the Ionians), in the form of ideas (Plato), or in the form of matter, eternal motion, and the first heavens (Aristotle). It is not strange then that calling this view into question by Tho- mas Aquinas was a revolutionary move which became a turning point in the interpretation of reality as a whole. The revolutionary character of Thomas’ approach was expressed in his perception of the fact that the world was contingent. The truth that the world as a whole and eve- rything that exists in the world does not possess in itself the reason for its existence slowly began to sink into the consciousness of philoso- phers. Everything that is exists, as it were, on credit. Hence the world and particular things require for the explanation of their reason for be- ing the discovery of a more universal cause than is the cause of motion. This article is a revised and improved version of its first edition: Andrzej Maryniarczyk SDB, The Realistic Interpretation of Reality. -

Being Qua Being

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/06/12, NEWGEN part iv BEING AND BEINGS 114_Shields_Ch14.indd4_Shields_Ch14.indd 334141 11/6/2012/6/2012 66:02:56:02:56 PPMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/06/12, NEWGEN 114_Shields_Ch14.indd4_Shields_Ch14.indd 334242 11/6/2012/6/2012 66:02:59:02:59 PPMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/06/12, NEWGEN Chapter 14 BEING QUA BEING Christopher Shields I. Three Problems about the Science of Being qua Being ‘There is a science (epistêmê),’ says Aristotle, ‘which studies being qua being (to on hê(i) on), and the attributes belonging to it in its own right’ (Met. 1003a21–22). This claim, which opens Metaphysics IV 1, is both surprising and unsettling—sur- prising because Aristotle seems elsewhere to deny the existence of any such science and unsettling because his denial seems very plausibly grounded. He claims that each science (epistêmê) studies a unified genus (APo 87a39-b1), but he denies that there is a single genus for all beings (APo 92b14; Top. 121a16, b7–9; cf. Met. 998b22). Evidently, his two claims conspire against the science he announces: if there is no genus of being and every science requires its own genus, then there is no science of being. This seems, moreover, to be precisely the conclusion drawn by Aristotle in his Eudemian Ethics, where he maintains that we should no more look for a gen- eral science of being than we should look for a general science of goodness: ‘Just as being is not something single for the things mentioned [viz.