Sudan and South Sudans Merging Conflicts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Draft of the Co-Chairman's Statement

FINAL DRAFT OF THE CO-CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT Your Excellencies, Honorable Delegates, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen, On behalf of my Co-Chairman, Moulana Abel Alier, my colleagues in the Steering Committee, and on my own behalf, I would like to extend a warm welcome to all of you to this Conference, which marks the final phase of the National Dialogue. This is a historic occasion for us in the National Dialogue and we believe for our country. When His Excellency, President Salva Kiir Mayardit, initiated the National Dialogue more than three years ago, we cannot say with confidence that we, or anyone else for that matter, had a clear idea how long it would take, where it would lead, and what the end result would be. It was initially thought that the Dialogue process would take several months. Many saw it as a ploy by the President to polish his political image. The National Dialogue has now lasted for over three years. And far from being a ploy by the President, it has proved to be a sincere national soul searching about the crises facing our country. 1 What we soon learned as we undertook our assignment, was that our President wanted the process to be absolutely free, inclusive, transparent and credible. He repeatedly reaffirmed that National Dialogue was not a trap or a net for catching his political opponents, and that people should speak freely without fear, harassment or any form of intimidation. And, indeed, through the nationwide grassroots consultations and regional conferences, our people spoke their minds without fear or constraint. -

Strategic Peacebuilding- the Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan

SPECIAL REPORT Strategic Peacebuilding The Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan The Cases of the SPLM Leadership Crisis (2013), the Military Standoff at General Malong’s House (2017), and the Wau Crisis (2016–17) NYATHON H. MAI JULY 2020 WEEKLY REVIEW June 7, 2020 The Boiling Frustrations in South Sudan Abraham A. Awolich outh Sudan’s 2018 peace agreement that ended the deadly 6-year civil war is in jeopardy, both because the parties to it are back to brinkmanship over a number S of mildly contentious issues in the agreement and because the implementation process has skipped over fundamental st eps in a rush to form a unity government. It seems that the parties, the mediators and guarantors of the agreement wereof the mind that a quick formation of the Revitalized Government of National Unity (RTGoNU) would start to build trust between the leaders and to procure a public buy-in. Unfortunately, a unity government that is devoid of capacity and political will is unable to address the fundamentals of peace, namely, security, basic services, and justice and accountability. The result is that the citizens at all levels of society are disappointed in RTGoNU, with many taking the law, order, security, and survival into their own hands due to the ubiquitous absence of government in their everyday lives. The country is now at more risk of becoming undone at its seams than any other time since the liberation war ended in 2005. The current st ate of affairs in the country has been long in the making. -

South Sudan's

Untapped and Unprepared Dirty Deals Threaten South Sudan’s Mining Sector April 2020 Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Invitation to Exploitation 4 Beneath the Battlefield: Mineral Development During Conflict 12 Indications of Possible Money Laundering 19 Recommendations 20 We are grateful for the support we receive from our donors who have helped make our work possible. To learn more about The Sentry’s funders, please visit The Sentry website at www.thesentry.org/about/. UNTAPPED AND UNPREPARED: DIRTY DEALS THREATEN SOUTH SUDAN’S MINING SECTOR TheSentry.org Executive Summary South Sudan’s mining sector has seen rapid development in recent years, and preliminary reports suggest that the industry could become an engine for major economic growth. However, ineffective accountability mechanisms, an opaque corporate landscape, and inadequate due diligence have exposed the sector to abuse by bad actors within South Sudan’s ruling clique. The Sentry has found that existing laws have proven insufficient bulwarks against abuse, raising concerns that the country’s mineral wealth could do little more than spur the kind of violent competition that has ravaged the oil sector. Although South Sudan took welcome steps to reform the mining sector in 2012, some government officials, their relatives, and their close associates have fostered a weak regulatory environment susceptible to exploitation. In one example of how the privileged few have apparently exploited kleptocratic arrangements, President Salva Kiir’s daughter partly owns a company with three active licenses, while another company with three licenses lists former Vice President James Wani Igga’s son as a shareholder. Ashraf Seed Ahmed Hussein Ali, a businessman commonly known as Al-Cardinal who was placed under Global Magnitsky sanctions in October 2019, reportedly owns the company currently holding the greatest number of licenses.1 In the gold-rich region of Kapoeta, state government officials have begun issuing licenses independently of the central government. -

The Crime of Genocide and International Law: a Perspective on the 1915 Events Erdoğan İşcan *

GİFGRF 23 April 2021 The Crime of Genocide and International Law: A Perspective on the 1915 Events Erdoğan İşcan * * Ambassador (R) Erdoğan İşcan is Member of the United Nations Committee Against Torture. He also teaches international human rights law at Istanbul Kültür University. He served as Ambassador to Ukraine, South Korea (also accredited to North Korea) and the Council of Europe in Strasbourg. He is currently a member of the Global Relations Forum. The Genocide Convention There is unquestionable consensus on the fact that genocide is the gravest crime against humanity. The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (hereinafter the Genocide Convention or the Convention), adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9 December 1948 and entered into force on12 January 1951, sets specific legal standards with a view to defining and identifying the acts which may amount to the crime of genocide. Currently, 152 Member States of the United Nations are parties to the Convention. There are also 41 signatures not followed by ratifications. It would thus be safe to assert that the Convention enjoys universal recognition and it is a legally binding component of international law. Turkey acceded to the Convention on 31 July 1950 without any reservation. Many States have ratified the Convention with a number of reservations. One example is the United States that ratified the Convention on 25 November 1988 with two “reservations”, five “understandings”, and one “declaration”. Article I of the Convention establishes genocide as an international crime “whether committed in time of peace or in time of war”, inviting the States to prevent and punish this crime. -

Measuring Up

Annual review 2016 The value we bring to media Measuring MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR There are many positive testimonials to the work of the foundation over the years from the thousands of alumni who have benefited from our training. The most heartening compliment, repeated often, is that a Thomson Foundation course has been “a life-changing experience.” In an age, however, when funders want a more quantifiable impact, it is gratifying to have detailed external evidence of our achievements. Such is the case in Sudan (pages 10-13) where, over a four-year period, we helped to improve the quality of reporting of 700 journalists from print, radio and TV. An independent evaluation, led by a respected media development expert during 2016, showed that 98 per cent of participants felt the training had given them tangible benefits, including helping their career development. The evaluation also proved that a long-running training programme had helped to address systemic problems in a difficult regime, such as giving journalists the skills to minimise self-censorship and achieve international Measuring standards of reporting. Measuring the effectiveness of media development and journalism training courses has long been a contentious our impact issue. Sudan shows it is easier to do over the long term. As our digital training platform develops (pages 38-40), it will also be possible to measure the impact of a training in 2016 course in the short term. Our interactive programmes have been designed, and technology platform chosen, specifically so that real-time performance data for each user can be made easily available and progress measured. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

Southern Sudan News Bulletin ______

Southern Sudan News Bulletin ___________________________________________________________________________ An Overview of UN Activities in Southern Sudan Published by the UN Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) _____________________________________________________________________ Vol. 4 Issue No.1 January 2009 Highlights: ¾ Thousands flee LRA attacks ¾ Sudan marks fourth CPA anniversary ¾ Former SPLA combatants turned into Prison Services Wardens ¾ Misseriya still in Southern Kordofan ¾ Planning underway for Tri-State Peace Conference ¾ Data compilation for essential services in Lakes State completed . Sector I – Juba Sudan Marks fourth CPA anniversary Thousands flee LRA attacks On January 9, Sudan marked the fourth Thousands of internally displaced persons anniversary of the Comprehensive Peace (IDPs) and refugees fleeing attacks by Agreement (CPA) that ended 21 years of Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) rebels have conflict between northern and southern poured into Western Equatoria State, Sudan in the Upper Nile State capital of prompting Governor Jemma Nunu Kumba to Malakal. The ceremony, which was attended launch a humanitarian appeal for by both the President of the Government of assistance. The displacement follows a joint National Unity (GONU), Omar Al Bashir, and military offensive by Ugandan and the First Vice-President of the GONU, Salva Congolese forces against the LRA that was Kiir, drew thousands of Sudanese to the launched on 14 December. The IDPs and city’s stadium. refugees, most of whom come from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), During the celebrations, President Bashir moved into Sudan after LRA attacks on and Vice-President Kiir, who is also their villages killed hundreds and led to the president of the Government of Southern abduction of women, children and even Sudan (GoSS), inaugurated the Malakal men. -

Informing the Blue Helmets: the United States, Un Peacekeeping Operations, and the Role of Intelligence

INFORMING THE BLUE HELMETS INFORMING THE BLUE HELMETS: THE UNITED STATES, UN PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS, AND THE ROLE OF INTELLIGENCE Robert E. Rehbein Centre for International Relations, Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada 1996 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Rehbein, Robert E., 1959– Informing the blue helmets : the United States, UN peace operations, and the role of intelligence (Martello papers, ISSN 1183-3661 ; 16) ISBN 0-88911-705-5 1. United Nations – United States. 2. Intelligence service – United States. 3. United Nations – Armed Forces. I. Queen’s University (Kingston, Ont.). Centre for International Relations. II. Title. III. Series. JX1977.2.U5RA 1996 341.2’373 C96-930235-5 © Copyright 1996 The Martello Papers The Queen’s University Centre for International Relations (QCIR) is pleased to present the sixteenth in its series of security studies, the Martello Papers. Taking their name from the distinctive towers built during the nineteenth century to defend Kingston, Ontario, these papers cover a wide range of topics and issues relevant to international strategic relations of today. Over the past several years, as peacekeeping activity has become more substan- tial in Europe and the Americas, the Centre has devoted increasing attention to it. The experience of peacekeepers in complex post-Cold War conflicts has under- lined the importance of intelligence capabilities in peacekeeping. Given the dearth of in-house intelligence resources in the United Nations system, it is frequently assumed that peacekeepers must rely to a considerable extent on national intelli- gence gathering capabilities, and notably those of the United States. This Martello Paper, by Robert Rehbein of the United States Air Force, addresses the question of US intelligence support for UN peace operations. -

1 AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O

AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: +251 11 551 7700 / +251 11 518 25 58/ Ext 2558 Website: http://www.au.int/en/auciss Original: English FINAL REPORT OF THE AFRICAN UNION COMMISSION OF INQUIRY ON SOUTH SUDAN ADDIS ABABA 15 OCTOBER 2014 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 3 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I ..................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER II .................................................................................................................. 34 INSTITUTIONS IN SOUTH SUDAN .............................................................................. 34 CHAPTER III ............................................................................................................... 110 EXAMINATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AND OTHER ABUSES DURING THE CONFLICT: ACCOUNTABILITY ......................................................................... 111 CHAPTER IV ............................................................................................................... 233 ISSUES ON HEALING AND RECONCILIATION ....................................................... -

Gatluak Gai's Rebellion, Unity State

Gatluak Gai’s Rebellion, Unity State Gatluak Gai’s rebellion is linked to the complex and high-stakes politics of Unity state. The site of horrific violence and significant casualties during the civil war, Unity is home to political dynamics that mirror tensions at the highest levels of the Southern government. Given the ongoing armed banditry and insecurity in the state, these rifts, driven by wartime ties and longstanding tribal alliances, are unlikely to be resolved in the run-up to the South’s independence on 9 July 2011. Although Gatluak was not a major player in state politics prior to the April 2010 elections, the Government of South Sudan (GoSS) was convinced that he was linked to Angelina Teny—wife of Vice-President Riek Machar—who ran as an ‘independent’ candidate for the Unity governorship, and thus perceived him as a threat. Consequently, the GoSS deployed additional Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) troops to the state, particularly in Mayom and Pariang counties (seasonal destinations of the migrating Missiriya) and along the border with South Kordofan. The increased SPLA presence was motivated by suspicions about Angelina’s political aspirations, as well as the army’s intention to neutralize any potential security threats, such as the Missiriya. Oil-rich Unity, which shares a tense and militarized border with North Sudan, is of particular strategic importance to the GoSS. Gatluak and his forces did not launch any attacks in Unity between June and December 2010. Nevertheless, the areas of the state where he initially operated—in and around Koch county, south of Bentiu, and in the centre of the state—continued to be insecure, with frequent incidents of banditry and armed violence. -

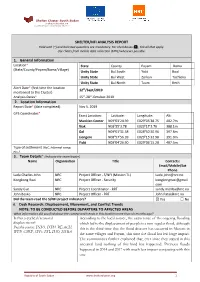

Shelter/Nfi Analysis Report 1

Shelter Cluster South Sudan sheltersouthsudan.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SHELTER/NFI ANALYSIS REPORT Field with (*) and italicized questions are mandatory. For checkboxes (☐), tick all that apply. Use charts from mobile data collection (MDC) wherever possible. 1. General Information Location* State County Payam Boma (State/County/Payam/Boma/Village) Unity State Bul South Yidit Bool Unity State Bul West Zorkan Tochloka Unity State Bul North Taam Kech Alert Date* (first time the location 12th/Sept/2019 mentioned to the Cluster) Analysis Dates* 15th-28th-October-2019 2. Location Information Report Date* (date completed) Nov 5, 2019 GPS Coordinates* Exact Location: Latitude: Longitude: Alt: Mankien Center N09003’24.99 E029005’38.75 402.7m Riak N08055’3.78 E029017’3.70 388.1m Gol N09001’31.38 E028050’40.96 397.8m Liengere N08057’56.39 E029015’32.98 391.0m Yidit N09004’26.90 E029006’15.20 407.5m Type of settlement (PoC, informal camp, etc.) 3. Team Details* (Indicate the team leader) Name Organisation Title Contacts: Email/Mobile/Sat Phone Ladu Charles John NRC Project Officer - S/NFI (Mission TL) [email protected] Kongkong Ruei NRC Project Officer - Security kongkongruei@gmail. com Sandy Gur NRC Project Coordinator - RRT [email protected] John Bosko NRC Project Officer - RRT [email protected] Did the team read the S/NFI project indicators? ☒ Yes ☐ No 4. Desk Research: Displacement, Movement, and Conflict Trends NOTE: TO BE CONDUCTED BEFORE DEPARTURE TO AFFECTED AREAS What information did you find about the context and trends in this location more than six months ago? Is this a cyclical/seasonal According to the local source, the occurrence of the ongoing flooding displacement? which led to the displacement of people is a non-regular flood, although Possible sources: INSO, DTM, REACH, this is the third time that the flood disaster has occurred in Mayom in WFP, CSRF, SFPs, FSL IMO, HSBA the same villages and Payam, this time the flood has left huge impact. -

Militia Politics

INTRODUCTION Humboldt – Universität zu Berlin Dissertation MILITIA POLITICS THE FORMATION AND ORGANISATION OF IRREGULAR ARMED FORCES IN SUDAN (1985-2001) AND LEBANON (1975-1991) Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil) Philosophische Fakultät III der Humbold – Universität zu Berlin (M.A. B.A.) Jago Salmon; 9 Juli 1978; Canberra, Australia Dekan: Prof. Dr. Gert-Joachim Glaeßner Gutachter: 1. Dr. Klaus Schlichte 2. Prof. Joel Migdal Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 18.07.2006 INTRODUCTION You have to know that there are two kinds of captain praised. One is those who have done great things with an army ordered by its own natural discipline, as were the greater part of Roman citizens and others who have guided armies. These have had no other trouble than to keep them good and see to guiding them securely. The other is those who not only have had to overcome the enemy, but, before they arrive at that, have been necessitated to make their army good and well ordered. These without doubt merit much more praise… Niccolò Machiavelli, The Art of War (2003, 161) INTRODUCTION Abstract This thesis provides an analysis of the organizational politics of state supporting armed groups, and demonstrates how group cohesion and institutionalization impact on the patterns of violence witnessed within civil wars. Using an historical comparative method, strategies of leadership control are examined in the processes of organizational evolution of the Popular Defence Forces, an Islamist Nationalist militia, and the allied Lebanese Forces, a Christian Nationalist militia. The first group was a centrally coordinated network of irregular forces which fielded ill-disciplined and semi-autonomous military units, and was responsible for severe war crimes.