I. Genre and Meaning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Epic of Gilgamesh Humbaba from His Days Running Wild in the Forest

Gilgamesh's superiority. They hugged and became best friends. Name Always eager to build a name for himself, Gilgamesh wanted to have an adventure. He wanted to go to the Cedar Forest and slay its guardian demon, Humbaba. Enkidu did not like the idea. He knew The Epic of Gilgamesh Humbaba from his days running wild in the forest. He tried to talk his best friend out of it. But Gilgamesh refused to listen. Reluctantly, By Vickie Chao Enkidu agreed to go with him. A long, long time ago, there After several days of journeying, Gilgamesh and Enkidu at last was a kingdom called Uruk. reached the edge of the Cedar Forest. Their intrusion made Humbaba Its ruler was Gilgamesh. very angry. But thankfully, with the help of the sun god, Shamash, the duo prevailed. They killed Humbaba and cut down the forest. They Gilgamesh, by all accounts, fashioned a raft out of the cedar trees. Together, they set sail along the was not an ordinary person. Euphrates River and made their way back to Uruk. The only shadow He was actually a cast over this victory was Humbaba's curse. Before he was beheaded, superhuman, two-thirds god he shouted, "Of you two, may Enkidu not live the longer, may Enkidu and one-third human. As king, not find any peace in this world!" Gilgamesh was very harsh. His people were scared of him and grew wary over time. They pleaded with the sky god, Anu, for his help. In When Gilgamesh and Enkidu arrived at Uruk, they received a hero's response, Anu asked the goddess Aruru to create a beast-like man welcome. -

The Epic of Gilgamesh: Tablet XI

Electronic Reserves Coversheet Copyright Notice The work from which this copy was made may be protected by Copyright Law (Title 17 U.S. Code http://www4.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/) The copyright notice page may, or may not, be included with this request. If it is not included, please use the following guidelines and refer to the U.S. Code for questions: Use of this material may be allowed if one or more of these conditions have been met: • With permission from the rights holder. • If the use is “Fair Use.” • If the Copyright on the work has expired. • If it falls within another exemption. **The USER of this is responsible for determining lawful uses** Montana State University Billings Library 1500 University Drive Billings, MT 59101-0298 (406) 657-1687 The Epic of Gilgamesh: Tablet XI The Story of the Flood Tell me, how is it that you stand in the Assembly of the Gods, and have found life!" Utanapishtim spoke to Gilgamesh, saying: "I will reveal to you, Gilgamesh, a thing that is hidden, a secret of the gods I will tell you! Shuruppak, a city that you surely know, situated on the banks of the Euphrates, that city was very old, and there were gods inside it. The hearts of the Great Gods moved them to inflict the Flood. Ea, the Clever Prince(?), was under oath with them so he repeated their talk to the reed house: 'Reed house, reed house! Wall, wall! O man of Shuruppak, son of Ubartutu: Tear down the house and build a boat! Abandon wealth and seek living beings! Spurn possessions and keep alive living beings! Make all living beings go up into the boat. -

Happily Ever After and Other Lies My Childhood Told Me Rachel Anna Neff University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2016-01-01 Happily Ever After And Other Lies My Childhood Told Me Rachel Anna Neff University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Neff, Rachel Anna, "Happily Ever After And Other Lies My Childhood Told Me" (2016). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 708. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/708 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HAPPILY EVER AFTER AND OTHER LIES MY CHILDHOOD TOLD ME RACHEL ANNA NEFF Master’s Program in Creative Writing APPROVED: Andrea Cote-Botero, Ph.D., Chair Sasha Pimentel Cheryl Torsney, Ph.D. Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Rachel Anna Neff 2016 Dedication To all the domesticated, feral, and wild hearts in my life who have shaped, challenged, and inspired me to become who I am today: these poems are for you. HAPPILY EVER AFTER AND OTHER LIES MY CHILDHOOD TOLD ME by RACHEL ANNA NEFF, BA English (2007), BA Spanish (2007), MA Spanish (2009), Ph.D. Spanish (2013) THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the -

Narrative Epic and New Media: the Totalizing Spaces of Postmodernity in the Wire, Batman, and the Legend of Zelda

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-17-2015 12:00 AM Narrative Epic and New Media: The Totalizing Spaces of Postmodernity in The Wire, Batman, and The Legend of Zelda Luke Arnott The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nick Dyer-Witheford The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Luke Arnott 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Arnott, Luke, "Narrative Epic and New Media: The Totalizing Spaces of Postmodernity in The Wire, Batman, and The Legend of Zelda" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3000. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3000 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NARRATIVE EPIC AND NEW MEDIA: THE TOTALIZING SPACES OF POSTMODERNITY IN THE WIRE, BATMAN, AND THE LEGEND OF ZELDA (Thesis format: Monograph) by Luke Arnott Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Luke Arnott 2015 Abstract Narrative Epic and New Media investigates why epic narratives have a renewed significance in contemporary culture, showing that new media epics model the postmodern world in the same way that ancient epics once modelled theirs. -

The Human Adventure Is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: the Next Generation

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY HONORS CAPSTONE The Human Adventure is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: The Next Generation Christopher M. DiPrima Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus Jackson General University Honors, Spring 2010 Table of Contents Basic Information ........................................................................................................................2 Series.......................................................................................................................................2 Films .......................................................................................................................................2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 How to Interpret Star Trek ........................................................................................................ 10 What is Star Trek? ................................................................................................................. 10 The Electro-Treknetic Spectrum ............................................................................................ 11 Utopia Planitia ....................................................................................................................... 12 Future History ....................................................................................................................... 20 Political Theory .................................................................................................................... -

![2020 Sergi Kataloğu [Indir]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8322/2020-sergi-katalo%C4%9Fu-indir-838322.webp)

2020 Sergi Kataloğu [Indir]

HACETTEPE ÜNİVERSİTESİ GÜZEL SANATLAR FAKÜLTESİ Yürütme Kurulu Düzenleme Kurulu Prof. Mümtaz Demirkalp (Dekan) Prof. M. Hakan Ertek Prof. Ayşe Sibel Kedik (Dekan Yrd.) Doç. Funda Susamoğlu Doç. Zuhal Boerescu (Dekan Yrd.) Doç. Ozan Bilginer Dr.Öğr. Üyesi M. Mesut Çelik Seçici Kurulu Dr.Öğr. Üyesi Tanzer Arığ Prof. Cebrail Ötgün Dr.Öğr. Üyesi Seza Soyluçiçek Prof. Hakan Ertek Arş.Gör. Pelin Koçkan Özyıldız Prof. Kaan Canduran Arş.Gör. İsmail Bezci Doç. Zülfükar Sayın Arş.Gör. Nagihan Gümüş Akman Doç. Funda Susamoğlu Doç. Ozan Bilginer Kapak, Afiş, Davetiye ve Banner Tasarımı Dr.Öğr. Üyesi M. Mesut Çelik Doç. Banu Bulduk Türkmen Dr.Öğr. Üyesi Şinasi Tek Dr.Öğr. Üyesi Tanzer Arığ Katalog Tasarımı Dr.Öğr. Üyesi Seza Soyluçiçek Dr.Öğr. Üyesi Seza Soyluçiçek Arş.Gör. Pelin Koçkan Özyıldız Tasarım Uygulama Dr.Öğr. Üyesi Seza Soyluçiçek Arş.Gör. Tuğba Dilek Kayabaş Arş.Gör. Cansu Başdemir Bu katalog 13 Temmuz - 28 Ağustos 2020 tarihleri arasında düzenlenen Fakültemizin lisans son sınıf öğrencilerinin yapıtlarından oluşan 2020 Sanat ve Tasarım Sanal Sergisi için hazırlanmıştır. İletişim Hacettepe Üniversitesi Güzel Sanatlar Fakültesi Dekanlığı Beytepe 06800 Ankara 0312 297 68 40-41 / www.gsf.hacettepe.edu.tr / [email protected] 2020 Sevgili Öğrenciler, Yetiştirdiği yaratıcı bireylerle ülke sanatına yön veren, ülkemizin sanat ortamının varlığını ve sürekliliğini sağlama yolunda önemli dinamikler oluşturan ve gerek ulusal gerekse uluslararası düzeyde önemli sanatsal katkılar sağlayan Hacettepe Üniversitesi Güzel Sanatlar Fakültesi, “2020 Sanat ve Tasarım Sergisi” ile önceki yıllarda olduğu gibi bu yıl da mezun öğrencilerimizin çalışmalarını bir araya getirmekte ve sergilemektedir. Güzel sanatlar eğitim-öğretim programımızın başarısını ortaya koyan en önemli gösterge, kuşkusuz ilerde ülkemiz sanatında söz sahibi olacak öğrencilerimizin sergileyecekleri başarıdır. -

The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh 47 The Epic of Gilgamesh Perhaps arranged in the fifteenth century B.C., The Epic of Gilgamesh draws on even more ancient traditions of a Sumerian king who ruled a great city in what is now southern Iraq around 2800 B.C. This poem (more lyric than epic, in fact) is the earliest extant monument of great literature, presenting archetypal themes of friendship, renown, and facing up to mortality, and it may well have exercised influence on both Genesis and the Homeric epics. 49 Prologue He had seen everything, had experienced all emotions, from ex- altation to despair, had been granted a vision into the great mystery, the secret places, the primeval days before the Flood. He had jour- neyed to the edge of the world and made his way back, exhausted but whole. He had carved his trials on stone tablets, had restored the holy Eanna Temple and the massive wall of Uruk, which no city on earth can equal. See how its ramparts gleam like copper in the sun. Climb the stone staircase, more ancient than the mind can imagine, approach the Eanna Temple, sacred to Ishtar, a temple that no king has equaled in size or beauty, walk on the wall of Uruk, follow its course around the city, inspect its mighty foundations, examine its brickwork, how masterfully it is built, observe the land it encloses: the palm trees, the gardens, the orchards, the glorious palaces and temples, the shops and marketplaces, the houses, the public squares. Find the cornerstone and under it the copper box that is marked with his name. -

Human Condition, the Prime Directive, and the Bardâ•Žs

Smith 1 Leah Smith Dr. Gideon Burton ENG 395 20 November 2016 Human Condition, the Prime Directive, and the Bard’s Connection with Star Trek The writings of William Shakespeare have been considered some of the best writing in human history and are often associated with high culture. Star Trek in contrast has been derided as a cult following group within pop culture portrayed on mass media television. However, throughout the period of time Star Trek has aired, there have been many episodes with both blatant and covert references to Shakespeare’s writings. Although Shakespeare may seem like a high culture phenomenon that has no place in a pop culture venue such as Star Trek, the connection between the two lies in the portrayal of the human condition and the hope for humanity that comes in recognizing ourselves in others. The year 2016 marks the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death and this has created an even more overwhelming celebration of his work through performance and dramatization. 2016 also marks the 50th anniversary of the creation of the Star Trek series. The alignment of these anniversaries is a coincidence but points to the significant connection that exists between the two. Shakespeare has always been a part of Star Trek and there are many episodes that contain references to plays, sonnets, characters, and Shakespeare in general. Many of these stem from the fact that many of the actors in Star Trek such as William Shatner, Patrick Stewart, Brent Spiner, and Christopher Plummer, were all Shakespearean actors in the theatre before they played these roles on the screen. -

CHARACTER DESCRIPTION Gilgamesh- King of Uruk, the Strongest of Men, and the Perfect Example of All Human Virtues. a Brave

CHARACTER DESCRIPTION Gilgamesh - King of Uruk, the strongest of men, and the perfect example of all human virtues. A brave warrior, fair judge, and ambitious builder, Gilgamesh surrounds the city of Uruk with magnificent walls and erects its glorious ziggurats, or temple towers. Two-thirds god and one-third mortal, Gilgamesh is undone by grief when his beloved companion Enkidu dies, and by despair at the fear of his own extinction. He travels to the ends of the Earth in search of answers to the mysteries of life and death. Enkidu - Companion and friend of Gilgamesh. Hairy-bodied and muscular, Enkidu was raised by animals. Even after he joins the civilized world, he retains many of his undomesticated characteristics. Enkidu looks much like Gilgamesh and is almost his physical equal. He aspires to be Gilgamesh’s rival but instead becomes his soul mate. The gods punish Gilgamesh and Enkidu by giving Enkidu a slow, painful, inglorious death for killing the demon Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven. Aruru - A goddess of creation who fashioned Enkidu from clay and her saliva. Humbaba - The fearsome demon who guards the Cedar Forest forbidden to mortals. Humbaba’s seven garments produce a feeling that paralyzes fear in anyone who would defy or confront him. He is the prime example of awesome natural power and danger. His mouth is fire, he roars like a flood, and he breathes death, much like an erupting volcano. In his very last moments he acquires personality and pathos, when he pleads cunningly for his life. Siduri - The goddess of wine-making and brewing. -

The Planetary Turn

The Planetary Turn The Planetary Turn Relationality and Geoaesthetics in the Twenty- First Century Edited by Amy J. Elias and Christian Moraru northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2015 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2015. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data The planetary turn : relationality and geoaesthetics in the twenty-first century / edited by Amy J. Elias and Christian Moraru. pages cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8101-3073-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8101-3075-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8101-3074-6 (ebook) 1. Space and time in literature. 2. Space and time in motion pictures. 3. Globalization in literature. 4. Aesthetics. I. Elias, Amy J., 1961– editor of compilation. II. Moraru, Christian, editor of compilation. PN56.S667P57 2015 809.9338—dc23 2014042757 Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Elias, Amy J., and Christian Moraru. The Planetary Turn: Relationality and Geoaesthetics in the Twenty-First Century. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2015. The following material is excluded from the license: Illustrations and an earlier version of “Gilgamesh’s Planetary Turns” by Wai Chee Dimock as outlined in the acknowledgments. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit http://www.nupress .northwestern.edu/. -

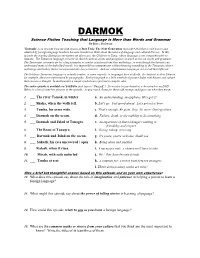

DARMOK Science Fiction Teaching That Language Is More Than Words and Grammar by Bryce Hedstrom

DARMOK Science Fiction Teaching that Language is More than Words and Grammar By Bryce Hedstrom "Darmok" is an episode from the fifth season of Star Trek: The Next Generation (episode #202) that is well known and admired by foreign language teachers because it makes us think about the nature of language and cultural literacy. In this episode the starship Enterprise encounters an alien race, the Children of Tama, whose language is not comprehensible to humans. The Tamarian language is based on shared cultural stories and metaphors as much as it is on words and grammar. The Tamarians communicate by citing examples or similar situations from their mythology, so even though the humans can understand many of the individual words, it is impossible to communicate without knowing something of the Tamarian culture, mythology and history that is incorporated into every sentence. And our actual human languages are not all that different. The fictitious Tamarian language is actually similar, in some respects, to languages here on Earth. In classical written Chinese, for example, ideas are represented by pictographs. Each pictograph is a little symbolical picture laden with history and culture that conveys a thought. In mathematics a simple symbol can represent a complex idea. The entire episode is available on YouTube (just type in “Darmok”). It can also be purchased as a download or on DVD. Below is a list of some key phrases in the episode. As you watch, listen for these odd sayings and figure out what they mean: 1. ___ The river Tamak, in winter a. An understanding, an epiphany. -

A New Function of the Scorpion-Man in the Ancient Near East

Bible Lands e-Review 2016/S1 Girtablullû and Co: A New Function of the Scorpion-Man in the Ancient Near East Nadine Nys, University of Ghent and University of Leuven Abstract Although there are great differences concerning the appearance of the scorpion-man, many researchers don't really differentiate between them when it comes to meaning and function, and even seem to forget there is also a third type that always appears in basically the same, outspoken function. The most familiar and benevolent type is the so-called Girtablullû: the human-headed and human-bodied creature with scorpion tail. This creature will be referred to in this article as Type 3. The scorpion-bird- and scorpion-scorpion-man belong to Type 2: creatures with human-head and bird- or scorpion-body respectively. The oldest type (therefore referred to as Type 1) can resemble both the human-bodied (Type 3), and the scorpion/bird-bodied types (Type 2). Thus, while both Type 3 and Type 2 can be identified by their iconography (human body or animal body, i.e. bird and scorpion respectively), Type 1 however, must be identified through its pose which is always "supportive", i.e., standing with its arms upraised to literally or virtually give support to either symbolic motifs (as the Sun-disc), or real-life objects (e.g. a throne). Type 1 is thus always shown in the same position. The different poses and/or differences in appearance do have an impact on the meaning and function of the composite creature, and are therefore worth keeping in mind when trying to analyse the meaning of images in which the creatures appear.