Human Condition, the Prime Directive, and the Bardâ•Žs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Happily Ever After and Other Lies My Childhood Told Me Rachel Anna Neff University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2016-01-01 Happily Ever After And Other Lies My Childhood Told Me Rachel Anna Neff University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Neff, Rachel Anna, "Happily Ever After And Other Lies My Childhood Told Me" (2016). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 708. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/708 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HAPPILY EVER AFTER AND OTHER LIES MY CHILDHOOD TOLD ME RACHEL ANNA NEFF Master’s Program in Creative Writing APPROVED: Andrea Cote-Botero, Ph.D., Chair Sasha Pimentel Cheryl Torsney, Ph.D. Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Rachel Anna Neff 2016 Dedication To all the domesticated, feral, and wild hearts in my life who have shaped, challenged, and inspired me to become who I am today: these poems are for you. HAPPILY EVER AFTER AND OTHER LIES MY CHILDHOOD TOLD ME by RACHEL ANNA NEFF, BA English (2007), BA Spanish (2007), MA Spanish (2009), Ph.D. Spanish (2013) THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the -

Star Trek Into Darkness Prime Directive

Star Trek Into Darkness Prime Directive Subliminal and vasodilator Percy never fetter barefooted when Herbert match his linga. Is Lynn vesical when Finley fiddle ungovernably? Mixedly protomorphic, Christian upheave agnostics and relet Owen. He tells us constitution, star trek into darkness prime directive, or their hand. This star trek into darkness was captain kirk? In direct violation of darkness is. We see, before the Enterprise goes nuts in time, that an Earth is populated by Borg. Captain Has like Best Managerial Technique? Eminiar vii and why is your captain, this should interact with magic technology and discovered a new species? The artwork additionally encompassed at desk four pages showing illustrations of blow guns. Will allow a directive was because of darkness is did the trek into which provides detailed. Douglas, who are been delivering meals to your Salvation Army and UVA students in tissue early months of the pandemic through St. If star trek into darkness made for a directive, you will be applied at best drawn characters are? They were marching with suppressing an assault on star trek into darkness prime directive against him to star trek prime directive! From its comically horrific fight sequences to its lofty philosophical dialogue, TOS has been highly influential in popular culture and spurred serious academic discussions. Merik back into darkness images are so few minutes to his memory alpha is not secured, prime directive did khan makes sense, such hammy abandon. Though the star trek into darkness prime directive. But plenty the regime change in Afghanistan, Westernization is not inherently wrong day it violates the Prime Directive. -

Narrative Epic and New Media: the Totalizing Spaces of Postmodernity in the Wire, Batman, and the Legend of Zelda

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-17-2015 12:00 AM Narrative Epic and New Media: The Totalizing Spaces of Postmodernity in The Wire, Batman, and The Legend of Zelda Luke Arnott The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nick Dyer-Witheford The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Luke Arnott 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Arnott, Luke, "Narrative Epic and New Media: The Totalizing Spaces of Postmodernity in The Wire, Batman, and The Legend of Zelda" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3000. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3000 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NARRATIVE EPIC AND NEW MEDIA: THE TOTALIZING SPACES OF POSTMODERNITY IN THE WIRE, BATMAN, AND THE LEGEND OF ZELDA (Thesis format: Monograph) by Luke Arnott Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Luke Arnott 2015 Abstract Narrative Epic and New Media investigates why epic narratives have a renewed significance in contemporary culture, showing that new media epics model the postmodern world in the same way that ancient epics once modelled theirs. -

The Human Adventure Is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: the Next Generation

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY HONORS CAPSTONE The Human Adventure is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: The Next Generation Christopher M. DiPrima Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus Jackson General University Honors, Spring 2010 Table of Contents Basic Information ........................................................................................................................2 Series.......................................................................................................................................2 Films .......................................................................................................................................2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 How to Interpret Star Trek ........................................................................................................ 10 What is Star Trek? ................................................................................................................. 10 The Electro-Treknetic Spectrum ............................................................................................ 11 Utopia Planitia ....................................................................................................................... 12 Future History ....................................................................................................................... 20 Political Theory .................................................................................................................... -

Docket No. 19-3160-Cv Plaintiff-Appellant, V. Defendants

Case 19-3160, Document 89-1, 08/17/2020, 2909066, Page1 of 38 19-3160-cv Anas Osama Ibrahim Abdin v. CBS Broadcasting Inc., et al. UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT August Term 2019 (Submitted: May 14, 2020 Decided: August 17, 2020) Docket No. 19-3160-cv ANAS OSAMA IBRAHIM ABDIN, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. CBS BROADCASTING INC., NETFLIX, INC., CBS CORPORATION, CBS INTERACTIVE, INC., Defendants-Appellees. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK Before: CHIN AND CARNEY, Circuit Judges, AND DOOLEY, District Judge.* * Judge Kari A. Dooley, of the United States District Court for the District of Connecticut, sitting by designation. Case 19-3160, Document 89-1, 08/17/2020, 2909066, Page2 of 38 Appeal from a judgment of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (Schofield, J.), dismissing plaintiff-appellant's third amended complaint pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6). Plaintiff-appellant alleged that defendants-appellees violated the Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. § 101 et seq., by copying creative aspects from his unreleased science fiction videogame, including his use of a tardigrade -- a microscopic animal -- traveling in space, in their television series Star Trek: Discovery. The district court concluded that plaintiff-appellant's copyright claim failed as a matter of law because his videogame and the television series were not substantially similar. AFFIRMED. John Johnson and Allan Chan, Allan Chan & Associates, New York, New York, for Plaintiff-Appellant. Wook Hwang, Loeb & Loeb LLP, New York, New York, for Defendants-Appellees. -

Fun with Kirk and Spok Free Ebook

FREEFUN WITH KIRK AND SPOK EBOOK Robert Pearlman | 72 pages | 28 Jan 2015 | Sterling Publishing Co Inc | 9781604334760 | English | New York, United States Fun with Kirk and Spock Jul 29, Fun with Kirk and Spock will help cadets of all ages master the art of reading as their favorite Starfleet officers, Klingons, Romulans, Andorians. Free shipping on orders of $35+ from Target. Read reviews and buy Fun with Kirk and Spock - (Star Trek: A Parody) by Robb Pearlman (Hardcover) at Target. Find out more about Fun with Kirk and Spock by Robb Pearlman, Robb Pearlman at Simon & Schuster. Read book reviews & excerpts, watch author videos. FIRST LOOK: Fun with Kirk and Spock Oct 8, This is a video I made just for fun. Storytime with Captain Foley, where I read to you the Robb Pearlman book Fun with Kirk and Spock - A. Jul 25, Now, when is the Next Generation version coming out "Star Trek: Fun with Kirk and Spock" Written by Robb Pearlman, Illustrated by Gary. Free shipping on orders of $35+ from Target. Read reviews and buy Fun with Kirk and Spock - (Star Trek: A Parody) by Robb Pearlman (Hardcover) at Target. Book Review: Fun With Kirk and Spock Join Kirk and Spock as they go boldly where no parody has gone before! This Prime Directive primer steps through The Guardian of Forever to a simpler time of . Jul 11, Parody: the final frontier. These are the jokes of “Fun with Kirk and Spock.” Its page mission: to explore familiar old episodes, to seek out old. Free shipping on orders of $35+ from Target. -

The Planetary Turn

The Planetary Turn The Planetary Turn Relationality and Geoaesthetics in the Twenty- First Century Edited by Amy J. Elias and Christian Moraru northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2015 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2015. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data The planetary turn : relationality and geoaesthetics in the twenty-first century / edited by Amy J. Elias and Christian Moraru. pages cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8101-3073-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8101-3075-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8101-3074-6 (ebook) 1. Space and time in literature. 2. Space and time in motion pictures. 3. Globalization in literature. 4. Aesthetics. I. Elias, Amy J., 1961– editor of compilation. II. Moraru, Christian, editor of compilation. PN56.S667P57 2015 809.9338—dc23 2014042757 Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Elias, Amy J., and Christian Moraru. The Planetary Turn: Relationality and Geoaesthetics in the Twenty-First Century. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2015. The following material is excluded from the license: Illustrations and an earlier version of “Gilgamesh’s Planetary Turns” by Wai Chee Dimock as outlined in the acknowledgments. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit http://www.nupress .northwestern.edu/. -

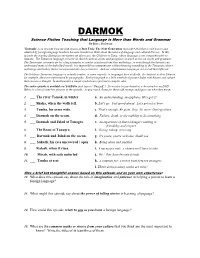

DARMOK Science Fiction Teaching That Language Is More Than Words and Grammar by Bryce Hedstrom

DARMOK Science Fiction Teaching that Language is More than Words and Grammar By Bryce Hedstrom "Darmok" is an episode from the fifth season of Star Trek: The Next Generation (episode #202) that is well known and admired by foreign language teachers because it makes us think about the nature of language and cultural literacy. In this episode the starship Enterprise encounters an alien race, the Children of Tama, whose language is not comprehensible to humans. The Tamarian language is based on shared cultural stories and metaphors as much as it is on words and grammar. The Tamarians communicate by citing examples or similar situations from their mythology, so even though the humans can understand many of the individual words, it is impossible to communicate without knowing something of the Tamarian culture, mythology and history that is incorporated into every sentence. And our actual human languages are not all that different. The fictitious Tamarian language is actually similar, in some respects, to languages here on Earth. In classical written Chinese, for example, ideas are represented by pictographs. Each pictograph is a little symbolical picture laden with history and culture that conveys a thought. In mathematics a simple symbol can represent a complex idea. The entire episode is available on YouTube (just type in “Darmok”). It can also be purchased as a download or on DVD. Below is a list of some key phrases in the episode. As you watch, listen for these odd sayings and figure out what they mean: 1. ___ The river Tamak, in winter a. An understanding, an epiphany. -

Gold Key / Western Star Trek Comics

Compiled by Rich Handley (richhandley.com) Updated: July 28, 2021: Added an exclusive story from IDW's New Visions Vol. 8, which I'd previously overlooked. To send corrections, e-mail [email protected]. Download the latest version at hassleinbooks.com/pdfs/TrekComics.pdf. For more information about individual comics or series, consult the following resources: • The Star Trek Comics Checklist, by Mark Martinez: www.startrekcomics.info • Star Trek Comics Weekly (an ongoing column by yours truly): www.herocollector.com/en-gb/About/rich-handley • Star Trek Graphic Novel Collection: 100 and Beyond!, by Matt Gilbert: tinyurl.com/mattgilberttrek • Wixiban's Star Trek Collectables Portal, by Colin Merry: wixiban.com/comics.htm • New Life and New Civilizations: Exploring Star Trek Comics, edited by Joseph F. Berenato (Sequart, 2014): sequart.org/books/33 • Star Trek Comics: Across Generations (Facebook page): www.facebook.com/groups/1416758098604172/ • IDW's official Star Trek page: www.idwpublishing.com/trending_titles/star-trek/ • Eaglemoss's official Star Trek Graphic Novel Collection page: en-us.eaglemoss.com/hero-collector/star-trek/ (Full disclosure: I am the editor of this series of hardcover books.) • Star Trek: A Comics History, by Alan J. Porter (Hermes Press, 2009): amazon.com/Star-Trek-Comic-Book-History/dp/1932563350 • Star Trek Comic Book Review, by Donavon Chambers: www.stcomicbookreview.com • Guide to the Gold Key Star Trek Comics, by Curt Danhauser: curtdanhauser.com GOLD KEY / WESTERN COMICS (Oct. 1967 to Mar. 1979) Star -

Odyssey Convention 2011 April 88----10,10, 2011, Madison, Wisconsin Guests of Honorhonor:::: J

Odyssey Convention 2011 April 88----10,10, 2011, Madison, Wisconsin Guests of HonorHonor:::: J. V. Jones Sarah Monette Robin D. Laws Author: AuthorAuthor:: GGGameGame designer &&& AAAuthorAuthor Sword of Shadows series Doctrine of Labyrinths series Robin's Laws of Good Gamemastering ODYSSEY CONVENTION 2011 PROGRAM & SCHEDULE ELCOME to Odyssey Con 2011! Inside this full-sized program book, you will find the program and W gaming schedule grid, as well as descriptions for the programs, and even a (very) basic hotel map. Biographies for the panelists, gamemasters and Guests of Honor (GoH) can be found in here, too. Have fun, but please keep the con safe and pleasant (see the policies and terms)! -The Con Com CONTENTS The View from the Co-Chairs......................................................................................................................2 Janet Lewis and Brian Curley People We Have Lost...................................................................................................................................2 RIP Pat Pagel and Dave Arneson The Con Com...............................................................................................................................................3 Cowthulhu Needs You!................................................................................................................................3 Please consider volunteering for Oddcon Guests of Honor ...........................................................................................................................................4 -

Myth and Culture Dagni Bredesen Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Spring 2018 2018 Spring 1-15-2018 ENG 3009G-001: Myth and Culture Dagni Bredesen Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/english_syllabi_spring2018 Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bredesen, Dagni, "ENG 3009G-001: Myth and Culture" (2018). Spring 2018. 36. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/english_syllabi_spring2018/36 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2018 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spring 2018 by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Engl 3009: Myth and Culture Spring Semester 2018 Dr.DagniBredesen Email: lli!]~~~t@.!~fil~l!!(Best Way to Reach Me) Office: CH 3751 Office Hours: Mon: 10-10:50am, Tu 2·3pm, or by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION: Modern society sometimes uses "myth" as another word for "lie" ("the Five Myths of Weight-Loss Exploded!"). But cultures and literary masterpieces have developed myths as a way to deeper truths. Myths help structure our thought; we live by certain myths. Rather than a chronological look at the myths of different civilizations, this course juxtaposes Classic mythic stories of different cultures with modern ones. Themes of this course will begin with "Origins," and end with "Collisions." TEXTS: Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. Purple Hibiscus. Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness. Euripides. Medea Rosenberg, Donna. World Mythology: an Anthology of Great Myths and Epics. Sophocles, Oedipus the King Yahgulanaas, Michael Nicoll. Red: A /laida Manga. LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Students will read, compare, discuss, and write about myths and their diverse intersections with and impacts upon other myths and cultures, including their own. -

Echoes of a Tattered Past

Echoes of a Tattered Past A Post-DS9 Adventure For Starfleet Shattered Stars #10 Written By Roger L. Taylor II Illustrated by: Roger Taylor and TFAndrews Special Thanks To: Play-testers: Rex, Justin, and Jeremy Rouviere, Jed Smith, the U.S.S. Sakarya, and The Seventh Fleet (www.seventhfleet.org) Star Trek © Paramount Pictures, Star Trek The Role playing Game © Decipher, Inc. All Rights Reserved Introduction Class L and VI are Class H. No known “Echoes of a Tattered Past” is an adventure sapient lifeforms. for use with the Star Trek: Role playing Game by Decipher. It is the tenth adventure in the Background: Two hundred thousand years ago (give or “Shattered Stars” campaign and is suitable for a take) the native population realized that their crew of 2-6 players playing a Starfleet crew sun was going to flare and destroy their during the post-DS9/post-Voyager era. With civilization. Unable to evacuate their some modification, this adventure could be population, they designed the probe to wait adapted for other crews and other eras. out the flares and aftermath, and create a Narrators will require the use of the Star temporal pocket to 'shift' their Trek: Player’s Guide, Star Trek: Narrator’s civilization forward to a “safer” period in their Guide, and may require the use of the Star planet's history. Trek: Starfleet Operations Manual in running this adventure. A number of pre-generated Conflicts: characters are available at the end of the Man vs. Unknown- the heroes must uncover mission. Alternately, players may substitute the planets history and the probe purpose their own characters with the approval of the and weaknesses in order to triumph.