A New Function of the Scorpion-Man in the Ancient Near East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Epic of Gilgamesh Humbaba from His Days Running Wild in the Forest

Gilgamesh's superiority. They hugged and became best friends. Name Always eager to build a name for himself, Gilgamesh wanted to have an adventure. He wanted to go to the Cedar Forest and slay its guardian demon, Humbaba. Enkidu did not like the idea. He knew The Epic of Gilgamesh Humbaba from his days running wild in the forest. He tried to talk his best friend out of it. But Gilgamesh refused to listen. Reluctantly, By Vickie Chao Enkidu agreed to go with him. A long, long time ago, there After several days of journeying, Gilgamesh and Enkidu at last was a kingdom called Uruk. reached the edge of the Cedar Forest. Their intrusion made Humbaba Its ruler was Gilgamesh. very angry. But thankfully, with the help of the sun god, Shamash, the duo prevailed. They killed Humbaba and cut down the forest. They Gilgamesh, by all accounts, fashioned a raft out of the cedar trees. Together, they set sail along the was not an ordinary person. Euphrates River and made their way back to Uruk. The only shadow He was actually a cast over this victory was Humbaba's curse. Before he was beheaded, superhuman, two-thirds god he shouted, "Of you two, may Enkidu not live the longer, may Enkidu and one-third human. As king, not find any peace in this world!" Gilgamesh was very harsh. His people were scared of him and grew wary over time. They pleaded with the sky god, Anu, for his help. In When Gilgamesh and Enkidu arrived at Uruk, they received a hero's response, Anu asked the goddess Aruru to create a beast-like man welcome. -

The Epic of Gilgamesh: Tablet XI

Electronic Reserves Coversheet Copyright Notice The work from which this copy was made may be protected by Copyright Law (Title 17 U.S. Code http://www4.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/) The copyright notice page may, or may not, be included with this request. If it is not included, please use the following guidelines and refer to the U.S. Code for questions: Use of this material may be allowed if one or more of these conditions have been met: • With permission from the rights holder. • If the use is “Fair Use.” • If the Copyright on the work has expired. • If it falls within another exemption. **The USER of this is responsible for determining lawful uses** Montana State University Billings Library 1500 University Drive Billings, MT 59101-0298 (406) 657-1687 The Epic of Gilgamesh: Tablet XI The Story of the Flood Tell me, how is it that you stand in the Assembly of the Gods, and have found life!" Utanapishtim spoke to Gilgamesh, saying: "I will reveal to you, Gilgamesh, a thing that is hidden, a secret of the gods I will tell you! Shuruppak, a city that you surely know, situated on the banks of the Euphrates, that city was very old, and there were gods inside it. The hearts of the Great Gods moved them to inflict the Flood. Ea, the Clever Prince(?), was under oath with them so he repeated their talk to the reed house: 'Reed house, reed house! Wall, wall! O man of Shuruppak, son of Ubartutu: Tear down the house and build a boat! Abandon wealth and seek living beings! Spurn possessions and keep alive living beings! Make all living beings go up into the boat. -

„…Of Uruk-The-Sheepfold”

Универзитет уметности у Београду Факултет музичке уметности Катедра за композицију ментор: Зоран Ерић, редовни професор Никола В. Ветнић „… o f U r u k - t h e - S h e e p f o l d ” за приповедача, сопран и камерни инструментални ансамбл ТЕОРИЈСКА СТУДИЈА О ДОКТОРСКОМ УМЕТНИЧКОМ ПРОЈЕКТУ Београд, 2016 Универзитет уметности у Београду Факултет музичке уметности Катедра за композицију ментор: Зоран Ерић, редовни професор Никола В. Ветнић „… o f U r u k - t h e - S h e e p f o l d ” за приповедача, сопран и камерни инструментални ансамбл ТЕОРИЈСКА СТУДИЈА О ДОКТОРСКОМ УМЕТНИЧКОМ ПРОЈЕКТУ Београд, 2016 САДРЖАЈ 1 ПОЛАЗИШТА.......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Ораторијум ХХ века ......................................................................................................7 1.2 (Ре)дефинисање ораторијума ........................................................................................9 1.3 Еп о Гилгамешу.............................................................................................................11 1.4 Утицаји..........................................................................................................................19 1.4.1 Socrate, Eric Satie ...................................................................................................19 1.4.2 Voices of Light, Richard Einhorn ............................................................................24 2 МУЗИКА У ДЕЛУ „...of Uruk-the-Sheepfold…” ..............................................................32 -

The Marriage of True Minds

THE MARRIAGE OF TRUE MINDS Of the Rise and Fall of the Idealized Conception of Friendship in the Renaissance Von der Gemeinsamen Fakultät für Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Hannover zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) genehmigte Dissertation von ROBIN HODGSON, M. A., geboren am 21.06.1969 in Neustadt in Holstein 2003 Referent: Prof. Dr. Gerd Birkner Korreferenten: Prof. Dr. Dirk Hoeges Prof. Dr. Beate Wagner-Hasel Tag der Promotion: 30.10.2003 ABSTRACT (DEUTSCH) Gegenstand der vorliegenden Untersuchung ist der Freundschaftsbegriff der Renaissance, der seinen Ursprung wesentlich in der antiken Philosophie hat, seine Darstellungsweisen in der europäischen (insbesondere der englischen und italienischen) Literatur des fünfzehnten und sechzehnten Jahrhunderts, und der Wandel, dem dieser beim Epochenwechsel zur Aufklärung im siebzehnten Jahrhundert unterworfen war. Meine Arbeit vertritt die Hypothese, dass sich die Konzeptionen der verschiedenen Formen zwischenmenschlicher Beziehung die sich spätestens seit dem achtzehnten Jahrhundert etablieren konnten, auf die konzeptionellen Veränderungen des Freund- schaftsbegriffs und insbesondere auf den Wandel des Begriffsverständnisses von Freundschaft und Liebe während der Renaissance und des sich anschließenden Epochenwechsels zurückführen lassen. Um diese Hypothese zu verifizieren, habe ich daher nach einer kurzen Übersicht über die konzeptionellen Ursprünge des frühneuzeitlichen Freundschaftsbegriffs zunächst das Wesen der primär auf den philosophischen -

![2020 Sergi Kataloğu [Indir]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8322/2020-sergi-katalo%C4%9Fu-indir-838322.webp)

2020 Sergi Kataloğu [Indir]

HACETTEPE ÜNİVERSİTESİ GÜZEL SANATLAR FAKÜLTESİ Yürütme Kurulu Düzenleme Kurulu Prof. Mümtaz Demirkalp (Dekan) Prof. M. Hakan Ertek Prof. Ayşe Sibel Kedik (Dekan Yrd.) Doç. Funda Susamoğlu Doç. Zuhal Boerescu (Dekan Yrd.) Doç. Ozan Bilginer Dr.Öğr. Üyesi M. Mesut Çelik Seçici Kurulu Dr.Öğr. Üyesi Tanzer Arığ Prof. Cebrail Ötgün Dr.Öğr. Üyesi Seza Soyluçiçek Prof. Hakan Ertek Arş.Gör. Pelin Koçkan Özyıldız Prof. Kaan Canduran Arş.Gör. İsmail Bezci Doç. Zülfükar Sayın Arş.Gör. Nagihan Gümüş Akman Doç. Funda Susamoğlu Doç. Ozan Bilginer Kapak, Afiş, Davetiye ve Banner Tasarımı Dr.Öğr. Üyesi M. Mesut Çelik Doç. Banu Bulduk Türkmen Dr.Öğr. Üyesi Şinasi Tek Dr.Öğr. Üyesi Tanzer Arığ Katalog Tasarımı Dr.Öğr. Üyesi Seza Soyluçiçek Dr.Öğr. Üyesi Seza Soyluçiçek Arş.Gör. Pelin Koçkan Özyıldız Tasarım Uygulama Dr.Öğr. Üyesi Seza Soyluçiçek Arş.Gör. Tuğba Dilek Kayabaş Arş.Gör. Cansu Başdemir Bu katalog 13 Temmuz - 28 Ağustos 2020 tarihleri arasında düzenlenen Fakültemizin lisans son sınıf öğrencilerinin yapıtlarından oluşan 2020 Sanat ve Tasarım Sanal Sergisi için hazırlanmıştır. İletişim Hacettepe Üniversitesi Güzel Sanatlar Fakültesi Dekanlığı Beytepe 06800 Ankara 0312 297 68 40-41 / www.gsf.hacettepe.edu.tr / [email protected] 2020 Sevgili Öğrenciler, Yetiştirdiği yaratıcı bireylerle ülke sanatına yön veren, ülkemizin sanat ortamının varlığını ve sürekliliğini sağlama yolunda önemli dinamikler oluşturan ve gerek ulusal gerekse uluslararası düzeyde önemli sanatsal katkılar sağlayan Hacettepe Üniversitesi Güzel Sanatlar Fakültesi, “2020 Sanat ve Tasarım Sergisi” ile önceki yıllarda olduğu gibi bu yıl da mezun öğrencilerimizin çalışmalarını bir araya getirmekte ve sergilemektedir. Güzel sanatlar eğitim-öğretim programımızın başarısını ortaya koyan en önemli gösterge, kuşkusuz ilerde ülkemiz sanatında söz sahibi olacak öğrencilerimizin sergileyecekleri başarıdır. -

The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh 47 The Epic of Gilgamesh Perhaps arranged in the fifteenth century B.C., The Epic of Gilgamesh draws on even more ancient traditions of a Sumerian king who ruled a great city in what is now southern Iraq around 2800 B.C. This poem (more lyric than epic, in fact) is the earliest extant monument of great literature, presenting archetypal themes of friendship, renown, and facing up to mortality, and it may well have exercised influence on both Genesis and the Homeric epics. 49 Prologue He had seen everything, had experienced all emotions, from ex- altation to despair, had been granted a vision into the great mystery, the secret places, the primeval days before the Flood. He had jour- neyed to the edge of the world and made his way back, exhausted but whole. He had carved his trials on stone tablets, had restored the holy Eanna Temple and the massive wall of Uruk, which no city on earth can equal. See how its ramparts gleam like copper in the sun. Climb the stone staircase, more ancient than the mind can imagine, approach the Eanna Temple, sacred to Ishtar, a temple that no king has equaled in size or beauty, walk on the wall of Uruk, follow its course around the city, inspect its mighty foundations, examine its brickwork, how masterfully it is built, observe the land it encloses: the palm trees, the gardens, the orchards, the glorious palaces and temples, the shops and marketplaces, the houses, the public squares. Find the cornerstone and under it the copper box that is marked with his name. -

Gilgamesh's Request and Siduri's Denial. Part 11: an Analysis and Interpretation of an Old Babylonian Fragment About Mourning and Celebration *

Gilgamesh's Request and Siduri's Denial. Part 11: An Analysis and Interpretation of an Old Babylonian Fragment about Mourning and Celebration * TZVI ABUSCH Brandeis University 1. Introduction The purpose of this essay is to provide an analysis of two of t.he most power fully evocative stanzas in Akkadian poetic literature. Such a study is surely fitting in a volume honoring Professor Yochanan Muffs. Yochanan's understanding of ancient texts is almost preternatural; one can only marvel at his ability to grasp and bring to life the emotions and metaphors that govern these texts. It seems ap propriate, then, to celebrate a great scholar and dear friend with a study of the form and, emotional force of passages from the Epic of Gilgamesh, passages that center upon themes which have also interested Yochanan. The two stanzas are part of the justly famous exchange between Gilgamesh and the divine tavernkeeper Siduri in an Old Babylonian (OB) version of the Epic of Gilgamesh. The preserved part of their encounter begins with a request that Gilgamesh addresses to Siduri followed by her response (= OB Gilg., Meissner, ii-iii).1 Each speech contains three stanzas. In translation, the two speeches read: col. ii * My friend, whom 1 love dearly. l' Who with me underwent all hardships, - d its companion study ("Gilgamesh's Request and Siduri's DeniaJ. Part 1: The Mean מ This essay a * ing of the Dialogue and ,its Implications for the History of the Epic." to appear in Sludies Hallo. ed . M, Cohen et al. [Bethesda, Maryland. 1993]) have benefitted greatly from the comments of several scholars, Stephen A. -

CHARACTER DESCRIPTION Gilgamesh- King of Uruk, the Strongest of Men, and the Perfect Example of All Human Virtues. a Brave

CHARACTER DESCRIPTION Gilgamesh - King of Uruk, the strongest of men, and the perfect example of all human virtues. A brave warrior, fair judge, and ambitious builder, Gilgamesh surrounds the city of Uruk with magnificent walls and erects its glorious ziggurats, or temple towers. Two-thirds god and one-third mortal, Gilgamesh is undone by grief when his beloved companion Enkidu dies, and by despair at the fear of his own extinction. He travels to the ends of the Earth in search of answers to the mysteries of life and death. Enkidu - Companion and friend of Gilgamesh. Hairy-bodied and muscular, Enkidu was raised by animals. Even after he joins the civilized world, he retains many of his undomesticated characteristics. Enkidu looks much like Gilgamesh and is almost his physical equal. He aspires to be Gilgamesh’s rival but instead becomes his soul mate. The gods punish Gilgamesh and Enkidu by giving Enkidu a slow, painful, inglorious death for killing the demon Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven. Aruru - A goddess of creation who fashioned Enkidu from clay and her saliva. Humbaba - The fearsome demon who guards the Cedar Forest forbidden to mortals. Humbaba’s seven garments produce a feeling that paralyzes fear in anyone who would defy or confront him. He is the prime example of awesome natural power and danger. His mouth is fire, he roars like a flood, and he breathes death, much like an erupting volcano. In his very last moments he acquires personality and pathos, when he pleads cunningly for his life. Siduri - The goddess of wine-making and brewing. -

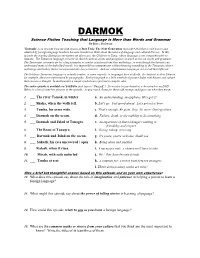

DARMOK Science Fiction Teaching That Language Is More Than Words and Grammar by Bryce Hedstrom

DARMOK Science Fiction Teaching that Language is More than Words and Grammar By Bryce Hedstrom "Darmok" is an episode from the fifth season of Star Trek: The Next Generation (episode #202) that is well known and admired by foreign language teachers because it makes us think about the nature of language and cultural literacy. In this episode the starship Enterprise encounters an alien race, the Children of Tama, whose language is not comprehensible to humans. The Tamarian language is based on shared cultural stories and metaphors as much as it is on words and grammar. The Tamarians communicate by citing examples or similar situations from their mythology, so even though the humans can understand many of the individual words, it is impossible to communicate without knowing something of the Tamarian culture, mythology and history that is incorporated into every sentence. And our actual human languages are not all that different. The fictitious Tamarian language is actually similar, in some respects, to languages here on Earth. In classical written Chinese, for example, ideas are represented by pictographs. Each pictograph is a little symbolical picture laden with history and culture that conveys a thought. In mathematics a simple symbol can represent a complex idea. The entire episode is available on YouTube (just type in “Darmok”). It can also be purchased as a download or on DVD. Below is a list of some key phrases in the episode. As you watch, listen for these odd sayings and figure out what they mean: 1. ___ The river Tamak, in winter a. An understanding, an epiphany. -

Scenes from the Epic of Gilgamesh Adapted From: Mccaughrean, Geraldine

Scenes from the Epic of Gilgamesh Adapted from: McCaughrean, Geraldine. Gilgamesh the Hero. Adapted by Abe Karplus. Cast (in order of appearance) Character Actor Archaeologist 1 Karen Archaeologist 2 Emily Archaeologist 3 Jake Enlil (chief god) Sean Shamash (sun god) Grant Ishtar (goddess of love and war) Jamie Ea (god of rivers) Madison Gilgamesh (king of Uruk) Abe Scorpion Man Eli Scorpion Woman Madison Siduri (woman with inn) Meggie Urshanabi (ferryman) Graham Utnapishtim (the immortal) Jack Saba (Utnapishtim’s wife) Aneesa The snake Cheyenne Scene 1: Archaeological dig in Iraq Archaeologists 1– 3 in front of stage, stage right, where they remain throughout play. Archaeologist 1: Look, what is that? Archaeologist 2: Oh, it’s cuneiform tablets! Archaeologist 3: What do they say? Archaeologist 1: Here, I think I can read them. Can you get me the dictionary and the magnifying glass? Archaeologist 2: OK, Professor, here you are. Archaeologist 3: What do they say? What do they say? Archaeologist 1: Will you be quiet so I can look at this! Archaeologist 2: They’re probably just warehouse records. Archaeologist 3: Maybe, maybe, but what do they say? Archaeologist 1: Let me see—it seems to be a story. The beginning seems to be missing. This bit says, “Gilgamesh, King of Uruk, sees the Scorpion People, they guard the entrance to a tunnel …” Archaeologist 2: This cuneiform tablet seems to have a title on it. Archaeologist 3: “The Epic of Gilgamesh” Archaeologist 1: Well, well, well, I’ll continue … Gods enter and remain in front of stage, stage left. Scene 2: In the Mashu Mountains Enlil (before stage): I am Enlil, God of the Wind. -

Ahmed Adnan Saygun'un Gilgameş Epik Dramı'na Metin Ve Müzik

The Journal of Musicology 2015 Cilt 1 Sayı 7/ 2015 Vol.1 Issue 7 ISSN: 2147-2807 Ahmed Adnan Saygun’un Gilgameş Epik Dramı’na Metin ve Müzik Perspektiflerinden Bir Bakış An Overview of Gilgamesh Epic Drama by Ahmed Adnan Saygun from the Perspectives of Text and Music Bülent YÜKSEL Partisyon ve Sayısal İşaret İşlemesinin Karşılıklı Etkileşimi: Jean-Claude Risset Variants Interdependencies Between Musical Score and Digital Signal Processing: Jean-Claude Risset Variants Onur DÜLGER On Music and Its Connection to the Will Müzik ve Müziğin İstenç ile İlişkisi Üzerine Ekin ÇORAKLI Poème Eléctronique: The Enormous Project of the Philips Pavilion Poème Eléctronique: Büyük Philips Pavyonu Projesi Lisa HELBIG ISSN 2147-2807 9 7 7 2 1 4 7 2 8 0 0 0 3 Müzik-Bilim Dergisi 2015 Cilt 1 Sayı 7 Hakem Kurulu/ Arbitration Committee of 2015 Vol. 1 Issue 7 of The Journal of Musicology Prof. Dr. M. Türker ARMANER, Galatasaray Üniversitesi, Felsefe Bölümü Prof. Dr. Nilgün DOĞRUSÖZ DİŞİAÇIK, İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi Türk Müziği Devlet Konservatuvarı, Müzik Teorisi Bölümü Prof. Özkan MANAV, Mimar Sinan Güzel Sanatlar Üniversitesi Devlet Konservatuvarı, Müzik Bölümü Prof. Dr. Kıvılcım YILDIZ ŞENÜRKMEZ, Mimar Sinan Güzel Sanatlar Üniversitesi Devlet Konservatuvarı, Müzikoloji Bölümü Doç. Dr. Tolga TÜZÜN, İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi, Sosyal ve Beşeri Bilimler Fakültesi, Müzik Bölümü Doç. Ahmet Altınel, Mimar Sinan Güzel Sanatlar Üniversitesi Devlet Konservatuvarı, Müzik Bölümü Doç. Dr. Mesut Erdem ÇÖLOĞLU, Anadolu Üniversitesi Devlet Konservatuvarı, Müzikoloji Bölümü Yrd. Doç. Dr. Yahya Burak TAMER, Bahçeşehir Üniversitesi, İletişim Fakültesi, İletişim Tasarımı Bölümü Yrd. Doç. Dr. Doğan YAŞAT, Mimar Sinan Güzel Sanatlar Üniversitesi, Sosyoloji Bölümü Yrd. -

The Epic of Gilgamesh: a Saga of Humanism Mythified

The Epic of Gilgamesh: A Saga of Humanism Mythified Ajay Kumar Gangopadhyay Associate Professor Department of English J.K. College, Purulia “Gilgamesh is stupendous”, - said Rainer Maria Rilke, after he read the translation of the epic made by the German Assyriologist Arthur Ungnad. Rilke observed that Gilgamesh was “das Epos der Todesfurcht” – “the epic about the fear of death”. Written in Cuneiform script in hundreds of tablets discovered from various places of ancient Mesopotemia, ostensibly by several hands through the centuries, Gilgamesh is the story of the eponymous hero who was the king of Uruk, a province of ancient Mesopotemia by the river Ufrates. This earliest effort to compose a great saga of human virility and quest for immortality, was started, as evidences certify, during 2600 B.C., though the systematic epical efforts started probably from 2100 B.C. The epic was discovered by modern Assyriologists Austen Henry Layard, Hormuzd Rassam and W.K. Loftus in 1853 from the ruins of the library in Nineveh of the 7th century B.C. Assyririan king Ashurbanipal. George Smith was the first modern translator of this epicwho made it during the 1970s, though the first Arabian translation by Taha Bariq was done in 1960s. This sumptuous saga has been translated in no less than sixteen languages, and the original story is scattered in more than eighty manuscripts retrieved from various places. The clay tablets have been found mainly in the ancient cities of Mesopotemia, the Levant and Anatolia, the sites in modern Iraq. The Cuneiform writing was invented in the city-states of lower Mesopotemia in about 3000 B.C.