Sample Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

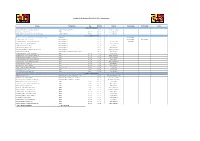

Teams Competition Age KO Time Referee Touch Judge

Castleford & Featherstone RLRS Match Official Appointments Teams Competition Age KO Time Referee Touch Judge Touch Judge In Goal In Goal Venue Thursday 15th September Wakefield Wildcats V Hull FC Super League Super 8's 20:00 Andy Sweet (RR) Featherstone Lions V Kippax Cas & District Cup Final U 13's 18:00 Jake Readman Tom Ambler Connor Astbury Joe Turner Cameron Worsley Mend-A-Hose Jungle Kippax V Lock Lane Cas & District Cup Final U 15's 19:15 Jake Butcher Joe Turner Cameron Worsley Tom Ambler Connor Astbury Mend-A-Hose Jungle Friday 16th September Featherstone Lions V Lock Lane YJRL U 11's 18:00 John Metcalfe Cutsyke Girls V TBC GIRLS League 18:30 Joe Turner Castleford Academy V TBC Schools 15:30 TBC Saturday 17th September East Leeds V Myton Warriors NCL Division 1 14:30 Cameron Worsley Milford Marlins V Thatto Heath Crusaders NCL Division 1 14:30 Joe Stearne Oulton Raiders V Hunslet Warriors NCL Division 1 14:30 Connor Astbury Jake Readman Ryan Kear Shaw Cross Sharks V Featherstone Lions NCL Division 1 14:30 Ellis McCarthy Skirlaugh V Underbank Rangers NCL Division 1 14:30 Brad Darlison Thornhill Trojans V Stanley Rangers NCL Division 2 14:30 Jake Butcher Eastmoor Dragons V Birkenshaw Blues Pennine ARL Division 3 14:30 Doug Martin Kippax Welfare V Millford Marlins YJRL U 10's 10:30 Ryan Kear Castleford Panthers V Dearne Valley YJRL U 10's 10:30 Jake Readman Brotherton Bulldogs V Oulton Riaders YJRL U 10's 10:30 Josh Goldie Brotherton Bulldogs V Illingworth YJRL U 11's 11:30 Ryan Smith Brotherton Bulldogs V York Acorn YJRL U 12's 12:30 -

RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1

rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1 RFL Official Guide 201 2 rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 2 The text of this publication is printed on 100gsm Cyclus 100% recycled paper rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1 CONTENTS Contents RFL B COMPETITIONS Index ........................................................... 02 B1 General Competition Rules .................. 154 RFL Directors & Presidents ........................... 10 B2 Match Day Rules ................................ 163 RFL Offices .................................................. 10 B3 League Competition Rules .................. 166 RFL Executive Management Team ................. 11 B4 Challenge Cup Competition Rules ........ 173 RFL Council Members .................................. 12 B5 Championship Cup Competition Rules .. 182 Directors of Super League (Europe) Ltd, B6 International/Representative Community Board & RFL Charities ................ 13 Matches ............................................. 183 Past Life Vice Presidents .............................. 15 B7 Reserve & Academy Rules .................. 186 Past Chairmen of the Council ........................ 15 Past Presidents of the RFL ............................ 16 C PERSONNEL Life Members, Roll of Honour, The Mike Gregory C1 Players .............................................. 194 Spirit of Rugby League Award, Operational Rules C2 Club Officials ..................................... -

Vs Dewsbury Moor

NATIONAL CONFERENCE LEAGUE TWO 2018 SEASON OFFICIAL MATCH DAY PROGRAMME S T C A L N R NI SA NGLEY Vs Saddleworth Rangers Vs DewsburySaturday 24th March Moor 2018 Match Ball Sponsored by The Crown & Anchor Rodley ADMISSION & PROGRAMME £2.50 www.stanningleyrugby.co.uk www.stanningleyrugby.co.uk The Crown & Anchor pub promises that you will be assured of a warm welcome and a friendly service. We offer the finest selection of beers and real ales. A great venue for special events with a relaxing Beer Garden to the rear. Come and have a drink - we look forward to seeing you soon. Football, rugby and horse racing on 5 large TV screens Saturday DJ 80’s and 90’s, 8pm - 12am Livemost FridayBands nights! S T C A L N R N SA INGLEY S T C VIEW FROM A L N R N SA THE CHAIR INGLEY SATURDAY 24TH MARCH 2018 Welcome to the players, officials and supporters from Saddleworth for this afternoons NCL Division 2 game. Honours were even last time we played in 2016, Saddleworth winning at their place 42 – 22 and we got the points at home 16 – 10. The season has really had a shocking start weather wise for some clubs, this is only Saddleworths second game of the season and no doubt they will be hoping to get off the mark after a defeat at Askam two weeks ago. We have been more fortunate with no postponements but after our flier in the first game away at Leigh East we have come a bit unstuck with defeats at home to Dewsbury Moor and away last week at Wigan St Judes. -

Queen Elizabeth II 1971-1995

16th June 1971. ‘Ulster 1971’ Paintings. 3p 7½p 9p ‘A Mountain Road’ ‘Deer’s Meadow’ ‘Slieve na brock’ T. P. Flanagan Tom Carr Colin Middleton © Gerard28th July 1971.J McGouran Literary Anniversaries. 2018 www.gbstampalbums.co.uk © Gerard J McGouran 2018 ©J Gerard 3p 5p 7½p John Keats Thomas Gray Sir Walter Scott 150th Death Anniversary Death Bicentenary Birth Bicentenary 25th August 1971. British Anniversaries. 3p 7½p 9p Servicemen and Nurse of 1921 Roman Centurion Rugby Football, 1871 www.gbstampalbums.co.uk © Gerard J McGouran 2018 QEII Decimal Commemoratives 1 22nd September 1971. British Architecture. Modern University Buildings. 3p 5p Physical Sciences Building, Faraday Building, Southampton University College of Wales, University Aberystwyth 7½p 9p ©Engineering Gerard Department, J McGouranHexagon Restaurant, 2018 Essex Leicester University University www.gbstampalbums.co.uk © Gerard J McGouran 2018 ©J Gerard 13th October 1971. Christmas. 2½p 3p 7½p ‘Dream of the Wise Men’ ‘Adoration of the Magi’ ‘Ride of the Magi’ www.gbstampalbums.co.uk QEII Decimal Commemoratives 2 16th February 1972. British Polar Explorers. 3p 5p 7½p 9p Sir James Clark Ross Sir Martin Frobisher Henry Hudson Capt. Robert F. Scott 26th April 1972. General Anniversaries. 3p © Gerard J McGouran7½p 2018 9p www.gbstampalbums.co.uk Statuette of Tutankhamun 19th Century Coastguard Ralph Vaughan Williams and Score © Gerard J McGouran 2018 ©J Gerard 21st June 1972. British Architecture. Village Churches. 3p 4p 5p St Andrew’s, Greensted- All Saints, Earls Barton, St Andrew’s, juxta-Ongar, Essex Northants Letheringsett, Norfolk 7½p 9p St Andrew’s, St Mary the Virgin, Huish Helpringham, Lincs Episcopi, Somerset www.gbstampalbums.co.uk QEII Decimal Commemoratives 3 13th September 1972. -

PDF Download

Huddersfield Local History Society Huddersfield Local History Society huddersfieldhistory.org.uk Journal No. 22 May 2011 The articles contained within this PDF document remain the copyright of the original authors (or their estates) and may not be reproduced further without their express permission. This PDF file remains the copyright of the Society. You are free to share this PDF document under the following conditions: 1. You may not sell the document or in any other way benefit financially from sharing it 2. You may not disassemble or otherwise alter the document in any way (including the removal of this cover sheet) 3. If you make the file available on a web site or share it via an email, you should include a link to the Society’s web site JournalJournal HuddersfieldHuddersfield LocalLocal History History SocietySociety MayMay 2011 2011 IssueIssue No: No: 22 22 128919.indd 1 26/04/2011 12:21:44 HUDDERSFIELD LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY was formed in 1977. It was established to HUDDERSFIELD LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY create a means by which peoples of all levels of experience could share their common interests in the history of Huddersfield and district. We recognise that WEBSITE: www.huddersfieldhistory.org.uk Huddersfield enjoys a rich historical heritage. It is the home town of prime ministers Email address: [email protected] and Hollywood stars; the birthplace of Rugby League and famous Olympic athletes; it has more buildings than Bath listed for historical or architectural interest; it had the SOCIETY OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE first municipal trams and some of the first council housing; its radical heritage includes the Luddites, suffragettes, pacifists and other campaigners for change. -

Annual Report

2015 RFL ANNUAL REPORT 2015 RFL ANNUAL RugbyRugby FootballFootball LeagueLeague AnnualAnnual ReportReport 20152015 RFL ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2015 CEO’s Review 4-6 Further Education 29 Chairman’s View 7 Schools 30-31 Board of Directors 8-9 Rugby League Cares 32-34 120 Years 10 Play Touch RL 35 Wembley Statue 11 Concussion 36 Magic Weekend 12 Cardiac Screening 37 World Club Series 13 Player Welfare 38-40 England Review 14-15 Hall of Fame 42 THE RUGBY Domestic Season Review 16-23 Safeguarding 43 FOOTBALL LEAGUE Events Review 24-25 RLEF Review 44-45 Red Hall, Red Hall Lane, Leeds, LS17 8NB Commercial Review 26-27 Operational Plan 46-47 T: 0844 477 7113 Higher Education 28 Financial Review 48-50 www.therfl .co.uk 3 The protocol on concussion was also CHIEF EXECUTIVE updated. Players suffering a suspected concussion during a game now have to undergo a proper assessment off the fi eld, with a free interchange allowed. The sport also mourned the passing OFFICER’S REPORT of Super League Match Offi cial Chris The year 2015 represented the 120th anniversary of the This secured their second trophy of the season, having already Leatherbarrow, a talented individual who creation of the sport of Rugby League and as was fi tting for this lifted the Ladbrokes Challenge Cup with a comprehensive win over tragically died at such a young age. momentous occasion, a number of celebratory events took place Hull Kingston Rovers at Wembley. A memorable treble beckoned to appropriately acknowledge this milestone. One of the biggest and it proved to be a nailbiting climax to the season when they VIEWERS AND was the Founders Walk, a 120-mile trek which took in each of the faced Wigan Warriors in the First Utility Grand Final. -

The Fax Time Machine

This newsletter is the idea The Fax Time of the officers of the Halifax RL Heritage Lunch Club, and Machine club historian Andrew Hardcastle. All correspond- ence should be sent to, Chris Mitchell c/o Halifax Panthers RLFC The Shay Stadium, Shay Syke, Halifax HX1 2YT Year 1 Edition 6 July 2021 RFL Hall of Fame This month we turn to the Rugby Football League's Hall of Fame and its connection with Halifax. Sadly it's rather slender.The scheme was launched in 1988, when experts selected 9 original inductees, the players considered to be the very greatest in the game's history. They were Harold Wagstaff, Jim Sullivan, Albert Rosenfeld, Gus Risman, Jonty Parkin, Alex Murphy, Billy Boston, Brian Bevan and Billy Batten Not much of a Halifax connection there, you might think. But you'd be wrong. One of them actually turned out for us once, and later became first team coach for a couple of seasons. Just which one it was will be revealed lower down. Since 1988 another 19 names have joined these originals. This time there are two Halifax connections, though not as players. Roger Millward, add- ed in the year 2000, was our coach from May 1991 to December 1992, when he was replaced by our other Hall of Fame link, Malcolm Reilly, who joined the roll of honour in 2014 Roger Millward at Thrum Hall, 1992. Malcolm Reilly, Halifax coach, 1994. front row far left Should there be a Halifax player in the Hall of Fame? Karl Harrison, record If we were to start a campaign for one, who would it GB caps for a Halifax be? If we went for the player who's scored most tries player. -

Oldham St Annes 16

#COYS SECOND TO NONE Saddleworth 22 Oldham St Annes 16 09.02.18 Standard Cup Semi Final As semi finals and derbies go, it doesn’t get much tougher going to Saddleworth Rangers on a cold, wet February afternoon. With Saints boasting a strong squad, Saddleworth opted to go with experience rather than youth in their line up and it was that quality that would be important in the result. The early exchanges were fierce, and Saddleworth certainly ramped up the pressure in the early stages pinning Saints in their own quarter. With ball in hand, Rangers thwarted the Saints attack with some strong defence, pushing them back time and time again. It was relentless, and it would take a great play to unlock the defence. As both sides were toughing it out through the middle, it took until the 23rd minute before the deadlock was broken, and it was the home side who scored in the right hand corner through Sam Hart. The conversion missed, Ranger lead 4 nil. This lead was short lived, as Saints started to get some better field position deep in the Saddleworth half. The visitors made this pay when Billy Barnes went from dummy half and bulldozed his way over the line to plant the ball over the line. Matt Whitehead added the extras, taking the Saints to a 6 points to 4 lead. 7 minutes later, Saints struck again as a chip over the top was collected by Dom Bryan who found Whitehead on his inside, and it was the stand off who romped under the posts to touch down an excellent worked move. -

Club Region Log in Reference Arlecdon ARLFC Cumbria

Please log in using the reference that corresponds to your club. If your club does not appear on the list you will then need to email [email protected] with the name of your club so that it can be added to your application. Cumbria Club Region Log In Reference Arlecdon ARLFC Cumbria CARLECDON Askam ARLFC Cumbria CASKAM Aspatria Hornets Cumbria CASPATRIA Barrow Island Cumbria CBARROWISLAND Barrow Referees Society Cumbria CBARROWREF Barrow RLFC Cumbria CBARROW Broughton Red Rose Cumbria CBROUGHTON Carlisle Gladiators Cumbria CCARLISLE Cockermouth Titans Cumbria CCOCKERMOUTH Cumbria Referee Society Cumbria CCUMBRIAREF Cumbria Storm Cumbria CCUMBRIASTORM Dalton ARLFC Cumbria CDALTON Distington Cumbria CDISTINGTON East Cumbria Crusaders Cumbria CEASTCUMBRIA Egremont Rangers Cumbria CEGREMONT Ellenborough Rangers Cumbria CELLENBOROUGH Flimby ARLFC Cumbria CFLIMBY Frizington ARLFC Cumbria CFRIZINGTON Glasson Rangers Cumbria CGLASSON Great Clifton ARLFC Cumbria CGREATCLIFTON Hensingham ARLFC Cumbria CHENSINGHAM Hindpool ARLFC Cumbria CHINDPOOL Kells ARLFC Cumbria CKELLS Lowca Cumbria CLOWCA Marsh Hornets Cumbria CMARSHHORNETS Hawcoat Storm Cumbria CHAWCOAT Maryport ARLFC Cumbria CMARYPORT Millom ARLFC Cumbria CMILLOM Penrith Pumas Cumbria CPENRITH Roose Pioneers Cumbria CROOSE Salterbeck Storm Cumbria CSALTERBECK Seaton Rangers Cumbria CSEATON Ulverston ARLFC Cumbria CULVERSTON Walney Central ARLFC Cumbria CWALNEY Wath Brow Hornets Cumbria CWATHBROW West cumbria Wildcats Cumbria CWESTCUMBRIA Whitehaven RLFC Cumbria CWHITEHAVEN Workington -

Club Region Log in Reference Arlecdon ARLFC Cumbria CARLECDON Askam ARLFC Cumbria CASKAM Aspatria Hornets Cumbria CASPATRIA Barr

Please log in using the reference that corresponds to your club. If your club does not appear on the list below please use the reference RFLCOMMUNITYCLUB, you will then need to email [email protected] with the name of your club so that it can be added to your application. Cumbria Club Region Log In Reference Arlecdon ARLFC Cumbria CARLECDON Askam ARLFC Cumbria CASKAM Aspatria Hornets Cumbria CASPATRIA Barrow Island Cumbria CBARROWISLAND Barrow Referees Society Cumbria CBARROWREF Barrow RLFC Cumbria CBARROW Broughton Red Rose Cumbria CBROUGHTON Carlisle Gladiators Cumbria CCARLISLE Cockermouth Titans Cumbria CCOCKERMOUTH Cumbria Referee Society Cumbria CCUMBRIAREF Cumbria Storm Cumbria CCUMBRIASTORM Dalton ARLFC Cumbria CDALTON Distington Cumbria CDISTINGTON East Cumbria Crusaders Cumbria CEASTCUMBRIA Egremont Rangers Cumbria CEGREMONT Ellenborough Rangers Cumbria CELLENBOROUGH Flimby ARLFC Cumbria CFLIMBY Frizington ARLFC Cumbria CFRIZINGTON Glasson Rangers Cumbria CGLASSON Great Clifton ARLFC Cumbria CGREATCLIFTON Hawcoat Storm Cumbria CHAWCOAT Hensingham ARLFC Cumbria CHENSINGHAM Hindpool ARLFC Cumbria CHINDPOOL Kells ARLFC Cumbria CKELLS Lowca Cumbria CLOWCA Marsh Hornets Cumbria CMARSHHORNETS Maryport ARLFC Cumbria CMARYPORT Millom ARLFC Cumbria CMILLOM Penrith Pumas Cumbria CPENRITH Roose Pioneers Cumbria CROOSE Salterbeck Storm Cumbria CSALTERBECK Seaton Rangers Cumbria CSEATON Ulverston ARLFC Cumbria CULVERSTON Walney Central ARLFC Cumbria CWALNEY Wath Brow Hornets Cumbria CWATHBROW West cumbria Wildcats Cumbria CWESTCUMBRIA -

HUDDERSFIELD LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY JOURNAL an Index of Articles from Issue 1 Autumn 1990 to Date, and from Its Predecessor the Newsletter from 1983-1990

HUDDERSFIELD LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY JOURNAL An index of articles from Issue 1 Autumn 1990 to date, and from its predecessor The Newsletter from 1983-1990. ALMONDBURY COURT ROLLS In mercy of the Lord, Almondbury Court Rolls ,part1 1627-41 Edited by Peter Hurst [Book reviewed in 22 May 2011, pp57-58] ARCHITECTS From miserable village to town of great character: from builder to architect. Ben Stocks and the growth of the architectural profession in Huddersfield. By Brian Haigh 21, Winter 2009-2010 ARMY RECRUITMENT Recruits for the haver cake lads By J H Rumsby Newsletter 2, 1984 ASIAN MIGRANTS TO HUDDERSFIELD Asian voices By Nafhesa Ali, Project Manager, centre for Oral History Research, University of Huddersfield 22, May 2011, pp7-25 BANK HOLIDAYS IN 1934 The sun had his hat on - at not infrequent intervals [Holme Valley festivities in 1934] 16, Winter 2004-2005 BAKESTONES By David Shore 13, Winter 2002/2003 BATH VILLA [The house that became Corra Lynn] in Corra Lynn 18, Winter 2006-2007 BEGGING A beggar‟s income [The earnings of a lame beggar, Joseph Walker, in 1860] 10, Winter 1999/2000. BERRY, GODFREY in Godfrey Berry and Thomas Wrigley: two pioneers of early urban Huddersfield By David Griffiths 19, Winter 2007-2008 BERRY BROW The end of the stone mason‟s yard: Berry Brow 16, Winter 2004-2005 BICKERSTETH‟S VISITATION Bishop Bickersteth‟s Visitation at Huddersfield, 1858 By J Addy Newsletter 5, 1986 BLACKMOORFOOT METHODIST CHAPEL Memories of Blackmoorfoot Methodist Chapel By Elaine Crabtree Winter 2005-2006 BOWER, JOSEPH Flooded but unbowed [The “Peter Pan grocer” of Hinchliffe Mill who lived to tell the tale, 82 years later] Winter 2005-2006 BRIGHOUSE, SAMUEL [Salendine Nook man who became a „founding father‟ of Vancouver, British Columbia] in Vancouver, British Columbia: an early Huddersfield connection. -

Teams Competition Age KO Time Referee Touch Judge Touch Judge

Castleford & Featherstone RLRS Match Official Appointments Teams Competition Age KO Time Referee Touch Judge Touch Judge Venue Friday 9th September Wakefield Wildcats V Catalan Dragons Super League Super 8's 20:00 Joe Stearne (IG) Lock Lane V East Leeds YJRL U 12's 18:30 Tom Ambler Oulton Raiders V Shawcross Sharks (GIRLS) Group 2 Phase 2 U 16's 19:00 John Metcalfe Saturday 10th September Newcastle Thunder U19's V Warrington Wolves U19's Academy 14:30 Doug Martin Featherstone Lions V Elland NCL Division 1 14:30 Tom Ambler Paul Clayton Hunslet Warriors V Underbank Rangers NCL Division 1 14:30 Ellis McCarthy Ryan Kear Myton Warriors V Oulton Raiders NCL Division 1 14:30 Connor Astbury Askam V Dewsbury Celtic NCL Division 2 14:30 Joe Turner Stanningley V Blackbrook NCL Division 2 14:30 Jake Butcher Thornhill Trojans V Saddleworth Rangers NCL Division 2 14:30 Cameron Worsley Drighlinton V Rylands NCL Division 3 (elimination play-off's) 14:30 Neil Horton Oulton Raiders V Leeds Underdogs YJRL U 10's 11:00 Ryan Smith Featherstone Lions V Fryston Warriors YJRL U 10's 10:30 Bailey Robinson Oulton Raiders V Eastmoor Dragons YJRL U 11's 10:30 Jake Readman Castleford Panthers V Hunslet Parkside YJRL U 11's 10:30 Ryan Kear Featherstone Lions V Kippax Welfare YJRL U 11's 11:30 Bailey Robinson Kippax Welfare V Keighley YJRL U 12's 11:30 Tom Ambler Featherstone Lions V Siddal YJRL U 12's 10:45 Paul Clayton Fryston Girls V Whitley Bay Girls GIRLS League U 12's 11:30 Josh Goldie Lock Lane V East Leeds YJRL U13's 12:30 John Metcalfe Kippax Welfare V Drighlington