Code Talker Joseph Bruchac Foreword

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Does This Seal Design Honor All Code Talkers and Why Is It Important to You?

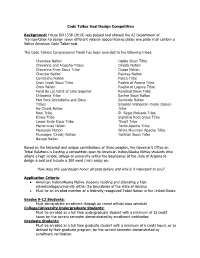

Code Talker Seal Design Competition Background: House Bill 1338 (2019) was passed and allowed the AZ Department of Transportation to design seven different veteran special license plates one plate shall contain a Native American Code Talker seal. The Code Talkers Congressional Medal has been awarded to the following tribes: Cherokee Nation Oglala Sioux Tribe Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes Oneida Nation Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe Osage Nation Choctaw Nation Pawnee Nation Comanche Nation Ponca Tribe Crow Creek Sioux Tribe Pueblo of Acoma Tribe Crow Nation Pueblo of Laguna Tribe Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Rosebud Sioux Tribe Chippewa Tribe Santee Sioux Nation Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Seminole Nation Tribes Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate (Sioux) Ho-Chunk Nation Tribe Hopi Tribe St. Regis Mohawk Tribe Kiowa Tribe Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Lower Brule Sioux Tribe Tlingit Tribe Menominee Nation Tonto Apache Tribe Meskwaki Nation White Mountain Apache Tribe Muscogee (Creek) Nation Yankton Sioux Tribe Navajo Nation Based on the historical and unique contributions of these peoples, the Governor’s Office on Tribal Relations is hosting a competition open to American Indian/Alaska Native students who attend a high school, college or university within the boundaries of the state of Arizona to design a seal and include a 300 word (min) essay on: How does this seal design honor all code talkers and why is it important to you? Application Criteria: ñ American Indian/Alaska Native students residing and attending a high school/college/university within -

Code Talkers Hearing

S. HRG. 108–693 CODE TALKERS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON CONTRIBUTIONS OF NATIVE AMERICAN CODE TALKERS IN AMERICAN MILITARY HISTORY SEPTEMBER 22, 2004 WASHINGTON, DC ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 96–125 PDF WASHINGTON : 2004 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado, Chairman DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii, Vice Chairman JOHN McCAIN, Arizona, KENT CONRAD, North Dakota PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico HARRY REID, Nevada CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota JAMES M. INHOFE, Oklahoma TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota GORDON SMITH, Oregon MARIA CANTWELL, Washington LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska PAUL MOOREHEAD, Majority Staff Director/Chief Counsel PATRICIA M. ZELL, Minority Staff Director/Chief Counsel (II) C O N T E N T S Page Statements: Brown, John S., Chief of Military History and Commander, U.S. Army Center of Military History ............................................................................ 5 Campbell, Hon. Ben Nighthorse, U.S. Senator from Colorado, chairman, Committee on Indian Affairs ....................................................................... 1 Inhofe, Hon. James M., U.S. Senator from Oklahoma .................................. 2 Johnson, Hon. -

Native Americans and World War II

Reemergence of the “Vanishing Americans” - Native Americans and World War II “War Department officials maintained that if the entire population had enlisted in the same proportion as Indians, the response would have rendered Selective Service unnecessary.” – Lt. Col. Thomas D. Morgan Overview During World War II, all Americans banded together to help defeat the Axis powers. In this lesson, students will learn about the various contributions and sacrifices made by Native Americans during and after World War II. After learning the Native American response to the attack on Pearl Harbor via a PowerPoint centered discussion, students will complete a jigsaw activity where they learn about various aspects of the Native American experience during and after the war. The lesson culminates with students creating a commemorative currency honoring the contributions and sacrifices of Native Americans during and after World War II. Grade 11 NC Essential Standards for American History II • AH2.H.3.2 - Explain how environmental, cultural and economic factors influenced the patterns of migration and settlement within the United States since the end of Reconstruction • AH2.H.3.3 - Explain the roles of various racial and ethnic groups in settlement and expansion since Reconstruction and the consequences for those groups • AH2.H.4.1 - Analyze the political issues and conflicts that impacted the United States since Reconstruction and the compromises that resulted • AH2.H.7.1 - Explain the impact of wars on American politics since Reconstruction • AH2.H.7.3 - Explain the impact of wars on American society and culture since Reconstruction • AH2.H.8.3 - Evaluate the extent to which a variety of groups and individuals have had opportunity to attain their perception of the “American Dream” since Reconstruction Materials • Cracking the Code handout, attached (p. -

Honor the Legacy of Navajo Code Talker Kee Etsicitty and Live Courageously

Honor the legacy of Navajo Code Talker Kee Etsicitty and live courageously Navajo Nation President Russell Begaye reads the proclamation he issued that ordered flags across the Navajo Nation to be flown at half-staff in honor of Navajo Code Talker Kee Etsicitty, who passed on July 21. He encouraged the audience to honor Etsicitty’s legacy by living courageously. (Photo by Rick Abasta) GALLUP, N.M.—The bells at home last October. MacDonald, Alfred Neuman and and Navajo Nation Council Sacred Heart Cathedral Church A member of the 3rd Bill Toledo were in attendance. Delegates Seth Damon, Otto tolled on the morning of July 24 Marines, 7th Division, Etsicitty The honor guards from the Tso and Leonard Tsosie. to honor the life of Navajo Code saw combat in the Battles of U.S. Marine Corps and the Ira H. Talker Kee Etsicitty. Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Hayes American Legion Post 84 Faithful Catholic, honorable His body was transported Guam, Saipan and Iwo Jima. from Sacaton, Ariz. were also on American to the church for the memorial hand to honor Etsicitty. According to Etsicitty’s son, services and escorted by the Paying respect to a hero A number of dignitaries Kurtis, his father was a devout members of the Navajo-Hopi Before he was laid to rest, came out to pay their respects, Catholic and said he wanted Honor Riders, the non-profit Etsicitty’s brothers came out including Navajo Nation his funeral services to be held organization that volunteered to honor him. Navajo Code President Russell Begaye, at Cathedral Church. His wish to repair the roof of Etsicitty’s Talkers Thomas H. -

From Scouts to Soldiers: the Evolution of Indian Roles in the U.S

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Summer 2013 From Scouts to Soldiers: The Evolution of Indian Roles in the U.S. Military, 1860-1945 James C. Walker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Walker, James C., "From Scouts to Soldiers: The Evolution of Indian Roles in the U.S. Military, 1860-1945" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 860. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/860 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM SCOUTS TO SOLDIERS: THE EVOLUTION OF INDIAN ROLES IN THE U.S. MILITARY, 1860-1945 by JAMES C. WALKER ABSTRACT The eighty-six years from 1860-1945 was a momentous one in American Indian history. During this period, the United States fully settled the western portion of the continent. As time went on, the United States ceased its wars against Indian tribes and began to deal with them as potential parts of American society. Within the military, this can be seen in the gradual change in Indian roles from mostly ad hoc forces of scouts and home guards to regular soldiers whose recruitment was as much a part of the United States’ war plans as that of any other group. -

Multiculturalism in the Armed Forces in the 20 Century

Multiculturalism in the Armed Forces in the 20th Century Cover: The nine images on the cover, from left to right and top to bottom, are: Japanese-American WACs on their way to Japan on a post-war cultural mission. (U.S. Army photo) African-American aviators in flight suits, Tuskegee Army Air Field, World War II. (Visual Materials from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Records; from the Library of Congress, Reproduction Number LC-USZ62-35362) During the visit of Lieutenant General Robert Gray, the Deputy Commander, USAREUR, Private First Class Donya Irby from the 44th Signal Company, out of Mannheim, Germany, describes how the 173 Van gathers, reads, and transmits signals to its destination as part of Operation Joint Endeavor. (Photo by Sergeant Angel Clemons, 55th Signal Company (comcam), Fort Meade, Maryland 20755. Image # 282 960502-A-1972C-003) U.S. Marine Corps Commandant General Carl E. Mundy poses for a picture with members of the Air Force fire department at Mogadishu Airport, Somalia. General Mundy toured the Restore Hope Theater during the Christmas holiday. (Photo by TSgt Perry Heimer, USAF Combat Camera) President George Bush takes time to shake hands with the troops and pose for pictures after his speech, January 1993, in Somalia. (Photo by TSgt Dave Mcleod, USAF Combat Camera) For his heroic actions in the Long Khanh Province in Vietnam, March 1966, Alfred Rascon (center), a medic, received the Medal of Honor three decades later. (Photo courtesy of the Army News Service) Navajo code talkers on Bouganville. (U.S. Marine Corps archive photo) On December 19, 1993, General John M. -

Choctaw Code Talkers of WWI and WWII

They Served They Sacrificed Telephone Warriors Choctaw Code Talkers Soldiers who used their native language as a weapon against the enemy, making a marked difference in the outcome of World War I Telephone Warriors - beginning the weapon of words Among the Choctaw warriors of WWI were fifteen members of the 142nd Infantry Regiment, a member of the 143rd and two members of the 141st Infantry Regiment who are now heralded as “WWI Choctaw Code Talkers.” All Regiments were part of the 36th Division. The Code Talkers from the 142nd were: Solomon Bond Lewis; Mitchell Bobb; Robert Taylor; Calvin Wilson; Pete Maytubby; James M. Edwards; Jeff Nelson; Tobias William Frazier; Benjamin W. Hampton; Albert Billy; Walter Veach; Joseph Davenport; George Davenport; Noel Johnson; and Ben Colbert. The member of the 143rd was Victor Brown and the Choctaw Code Talkers in the 141st were Ben Carterby and Joseph Okla- hombi. Otis Leader served in the 1sr Division, 16th Infantry. All of these soldiers came together in WWI in France in October and November of 1918 to fight as a unified force against the enemy. On October 1, 1917, the 142nd was organized as regular infantry and given training at Camp Bowie near Fort Worth as part of the 36th Division. Transferred to France for action, the first unit of the division arrived in France, May 31, 1918, and the last August 12, 1918. The 36th Division moved to the western front on October 6, 1918. Although the American forces were late in entering the war that had begun in 1914, their participation provided the margin of victory as the war came to the end. -

NEWSLETTER-JUNE-2016.Pdf

VOLUME 2, ISSUE 8 JUNE 2016 JUNE Funded & Distributed by the Ponca Tribe NEWSLETTER PONCA TRIBE OF OKLAHOMA The Code Talkers Recognition Act of 2008 The Code Talkers Recognition Act of 2008, authorized by Public Law 110-420 recogniz- es the dedication and valor of Native Ameri- can Code Talkers to the U.S. Armed Forces during World War I and World War II. In the Act Sec. 3 Findings (8)The United States Army recruited approximately 50 Native Special points of interest: Americans for special native language com- SENIOR CENTER munication assignments. (10)During World War II, the United States employed Native VETERANS MEMORIAL American code talkers who developed se- SASP PROGRAM cret means of communication based on SUMMER LUNCH native languages and were critical to win- ning the war. (14)The Congress should provide to all Native American code talkers the recognition the code talkers deserve for Inside this issue: the contributions of the code talkers to United States victories in World War I and PONCA TRIBE VETERANS MEMORI- 1 World War II” In an effort to meet the re- quirement set forth in the Act a list was PONCA TRIBE CODE TALKER 2 On 5/30/2016 Family of William Terry (Big) Snake received Silver Medal that was Dedicated during provided which showed the names and trib- VETERANS MEMORIAL 3 al affiliation. VETERANS LIST OF NAMES 4-5 the Veterans Memorial 2013. (Pictured left to right) LITTLE STANDING BUFFALO POST 6 Greg Victors, Ponka-We Victors, Sandy Victors, The United State Mint under Public Law HONOR VETERANS 7 Shude Victors U.N. -

Island Hopping: the Story of Ned Begay Code Talker: a Novel About the Navajo Marines of World War Two

Island Hopping: The Story of Ned Begay Code Talker: A Novel About the Navajo Marines of World War Two Students learn geographic concepts through the story of Code Talkers in WWII. Author Jessica Medlin Grade Level 4 Duration 2 class periods National Geography Arizona Geography Strand Other Arizona Standards Standards ELEMENT ONE: Grade 4 Grade 4 THE WORLD IN Concept 1: The World in Spatial Strand 1 American History SPATIAL TERMS Terms Concept 8 Great Depression and World 1. How to use maps PO 2 Interpret political and War II PO 3. Describe the impact of World and other physical maps using the following War II on Arizona (Native American geographic map elements: contributions) representations, e. scale tools, and PO 7 Locate physical and human ELA Common Core Standards technologies to features in Arizona using maps, Reading acquire, process, illustrations, or images. Literature and report Concept 2: Places and Regions Key Ideas and Details information from a PO 1 Describe how the Southwest 4.RL.1 spatial perspective. has distinct physical and cultural Refer to details and examples in a text characteristics. when explaining what the text says ELEMENT FOUR: explicitly and when drawing inferences PLACES AND from the text REGIONS 4.RL.3 4. The physical and Describe in depth a character, setting, or Human event in a story or drama, drawing on Characteristics of specific details in the text (e.g., a Places character’s thoughts, words, or actions). Writing Research to Build and Present Knowledge 4.W.9 Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research. -

2017 Released Items Grade 6 English Language Arts/Literacy Research

Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers Grade 6 English Language Arts/Literacy Research Simulation Task 2017 Released Items English Language Arts/Literacy 2017 Released Items: Grade 6 Research Simulation Task The Research Simulation Task requires students to analyze an informational topic through several articles or multimedia stimuli. Students read and respond to a series of questions and synthesize information from multiple sources in order to write an analytic essay. The 2017 blueprint for PARCC’s grade 6 Research Simulation Task includes Evidence-Based Selected Response/Technology-Enhanced Constructed Response items as well as one Prose Constructed Response prompt. Included in this document: • Answer key and standards alignment • PDFs of each item with the associated text(s) Additional related materials not included in this document: • Sample scored student responses with practice papers • PARCC Scoring Rubric for Prose Constructed Response Items • Guide to English Language Arts/Literacy Released Items: Understanding Scoring 2016 • PARCC English Language Arts/Literacy Assessment: General Scoring Rules for the 2016 Summative Assessment English Language Arts/Literacy PARCC Release Items Answer and Alignment Document ELA/Literacy: Grade 6 Text Type: RST Passage(s): from Navajo Code Talkers / "American Indians in the United States Army" / "What's So Special About Secret Codes?" from Destroy After Reading: The World of Secret Codes Item Code Answer(s) Standards/Evidence Statement Alignment 3872_A Item Type: EBSR -

Navajo Code Talker

Grandpa was a Navajo Code Talker DES MOINES, Iowa (AP) – Football often is compared to combat. Drake quarterback Ira Vandever knows better. Vandever understands that such comparisons don't do justice to those who actually endured combat, people like his grandfather and those who served with him. As a youngster, Vandever sat wide-eyed and hung on every word as his grandfather, Joe Vandever, recounted his days with the U.S. Marines in the Pacific during World War II. Grandpa talked mostly about the action, how the bullets flew and the mortars exploded, but his role went beyond shooting a rifle. A full-blooded Navajo, Joe Vandever was a code talker. Vandever was among the 400 or so Navajos who relayed coded messages via radio and walkie-talkie in their native language to confuse the Japanese. It worked because their language has no alphabet or symbols and was spoken only on the Navajo lands in the American Southwest. The Japanese never deciphered it. "Even if you knew the language, you still wouldn't know the code," Joe Vandever said. "It was never broken and never will be. If another war comes, we could just change it." Their contributions ignored for years, the code talkers were honored at the Pentagon in 1992. Further recognition came when President Bush presented gold medals to a group of code talkers last year and with the release of the movie "Windtalkers," which stars Nicholas Cage as a Marine assigned to protect a code talker. Ira Vandever found fault with the movie – too much focus on Cage's character, not enough on the Navajos – but is glad it was made. -

Language Arts / Social Studies Lesson Plan Language & Talking

Language Arts / Social Studies Lesson Plan Language & Talking Code Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings: OSEU 6.9-12.3 Students will be able to analyze the cause and effect on loss of cultural identity of the Oceti Sakowin. OSEU 7.9-12.2 - Students are able to identify the positive effects that Tribal people have initiated for social change. Common Core State Standards: RL8.4 - Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative and connotative meanings; analyze the impact of specific word choices on meaning and tone, including analogies or allusions to other texts. RI8.3—Analyze how a text makes connections among and distinctions between individuals, ideas, or events (e.g., through comparisons, analogies, or categories). SL8.1 – Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grade 8 topics, texts, and issues, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clarity. RH6-8.7-- Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts. Introduction: Indigenous languages, including Lakota, Dakota and Nakota, have been threatened historically by laws and policies that prevented them from being passed on generationally WWI and WWII provided an opportunity for many speakers of Native American languages to become Code Talkers and use their language to save lives and protect vital communications from interception All languages are “codes” and sometimes the purpose of language use is to communicate, sometimes the purpose is to prevent communication Many Native American code talkers who were not honored in the past, have been recognized for their service in recent years Many Lakota, Dakota and Nakota speakers provided code talker services during WWII Language Arts Lesson: Show clip from PBS Evolutionary Origins of Language video at http://youtu.be/maUN3asrHAo o Whole Class Circle Discussion: .