Together // Alone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Popular Music 27:02 Reviews

University of Huddersfield Repository Colton, Lisa Kate Bush and Hounds of Love. By Ron Moy. Ashgate, 2007. 148 pp. ISBN 978-0-7546-5798-9 (pb) Original Citation Colton, Lisa (2008) Kate Bush and Hounds of Love. By Ron Moy. Ashgate, 2007. 148 pp. ISBN 978-0-7546-5798-9 (pb). Popular Music, 27 (2). pp. 329-331. ISSN 0261-1430 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/2875/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Reviews 329 the functions and (social) interactions of the body as a defined biological system and ultimate representation of the self can be said to form the core of the argument. The peculiar discourse that arises from this kind of emphasis leads to a mesmerising and occasionally amusing line of progression endowing the book with a highly ramified structure, almost in itself an example of a maximalist procedure. -

My Favourite Album: Kate Bush's Hounds of Love Available From

My favourite album: Kate Bush's Hounds of Love David McCooey, The Conversation, 8 September 2017. Available from : https://theconversation.com/my-favourite-album-kate-bushs-hounds-of-love-79899 ©2017, Conversation Media Group Reproduced by Deakin University under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives Licence Downloaded from DRO: http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30102609 DRO Deakin Research Online, Deakin University’s Research Repository Deakin University CRICOS Provider Code: 00113B Academic rigour, journalistic flair September 8, 2017 11.24am AEST The album is an artistic statement, a swag of songs greater than the sum of its parts. In Author a new series, our authors nominate their favourites. David McCooey Professor of Writing and Literature, Deakin University Kate Bush’s Hounds of Love (1985) was the first album I heard on CD. With its use of the Fairlight CMI (a digital synthesizer/sampler workstation), digital reverb, and drum machines, it was perhaps eminently suitable for the CD format. But under its shiny digital sound, Hounds of Love was very much an LP, as seen in its two-part structure. Side one, Hounds of Love, covers themes characteristic of Bush: intimacy and its limits (Running Up That Hill (A Deal With God) and The Big Sky); familial love (albeit darkly articulated in Mother Stands for Comfort); and the intensity and ambivalence of sexual desire (Hounds of Love). Meanwhile, side two comprises of The Ninth Wave, a song cycle about a woman who has fallen into the sea at night, with only the “little light” of her life jacket to guide her. -

Kate Bush: Running up That Hill Again? | Nouse

Nouse Web Archives Kate Bush: Running up that hill again? Page 1 of 3 News Comment MUSE. Politics Business Science Sport Roses Freshers Muse › Music › News Features Reviews Playlists Kate Bush: Running up that hill again? Katy Sandalls reflects on Kate Bush’s career and speculates on her first tour since 1979 Friday 21 March 2014 Photo credit: Vintage Vision “Out on the Wiley, windy moors we’d roll and fall in green.” Kate Bush has never been a conventional artist, but that has always been her trademark and the reason why her fans adore her. It is unsurprising then that she has created a buzz in the music world once again by announcing that she is to go on tour for only the second time in her career. Kate Bush has had a phenomenal amount of success during her 35-year career with hits such as ‘Babooshka’ and ‘Running Up that Hill’. She has also received a Brit award and an Ivor Novello, as well as three Grammy nominations. Last year she was awarded a CBE by the Queen. Bush’s original tour was back in 1979 at the very start of her career, following her very successful debut album The Kick Inside, which featured Bush’s most famous song ‘Wuthering Heights’. But after those six weeks she never toured again, and was very rarely seen performing live, finding her own performance on Top of the Pops embarrassing. She even turned down an opportunity to perform at the 2012 Olympic closing ceremony. So why has it taken Bush nearly 40 years to consider going on tour again? Bush’s The Tour of Life was seen as real spectacle by those who attended; full of wondrous special effects and fabulous costume changes (17 in total!). -

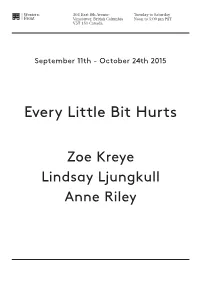

Every Little Bit Hurts

303 East 8th Avenue Tuesday to Saturday Vancouver, British Columbia Noon to 5:00 pm PST V5T 1S1 Canada September 11th - October 24th 2015 Every Little Bit Hurts Zoe Kreye Lindsay Ljungkull Anne Riley have led to the complete collapse of Every Little society as we know it. In this reality, where violence has become the new Bit Hurts norm, Lauren Olamina’s condition as a hyperempath, or “sharer” as those Setting the tone. If you are so inclined, with this condition are sometimes you might accompany your reading called, is particularly complicated. of this text with the following video/ audio clips: Though the concerns of Anne Riley, Zoe Kreye and Lindsay Ljungkull’s works Brenda Holloway’s “Every Little Bit in Every Little Bit Hurts do indeed Hurts”: https://youtu.be/kZf_rppcnm8; seem quite far from the concerns of Butler’s post-apocalyptic science The closing scene of Claire Denis’ fiction novels, I’ve returned time and 1999 film Beau travail: https://vimeo. again to this idea of the hyperempath com/105411522; throughout the process of working on this show. For the “sharers” in Butler’s Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill”: novels, their empathy with other https://youtu.be/wp43OdtAAkM. beings1 is not only felt emotionally, but literally felt in their own body. For now, hold those thoughts, I may In the novels this quality defines the come back to them later. But first, let’s essential worldview of Olamina’s take another dérive, and spend some character as she works towards the time considering the science fiction building of a new society, even amidst writer Octavia Butler. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Download The

TE NE WOMAN by Leah Kardos Dr Leah Kardos is an experienced musicologist She was lucky in many ways: privileged with aspect of her music product. Across her first three style, since it was seen to represent cultural elitism and senior lecturer in music at Kingston early access to musical tuition, familial support and albums, The Kick Inside, Lionheart (both 1978) in an era of widespread economic hardship and University. plenty of encouragement. Crucially, she had well- and Never for Ever (1980), and including her first social unrest. American pop in the late Seventies respected men in the music business advocating for major touring production (the Tour of Life, 1979), was on a different planet altogether, concerning ‘Wuthering Heights’ – a profoundly unlikely hit, her during the early stages of her development. Her we can track Kate’s evolution from a label-groomed itself with notions of authenticity and cultivating sitting as it did in the 1978 landscape of post-punk family helped her to produce a demo tape of original pop-star project towards her emergence as a fully a disciplined, precise production aesthetic. (Think and dance-floor fodder such as Boney M – signalled compositions, which was brought to the attention formed self-producing artist. The stylistic journey of the polished sonic surfaces of Fleetwood Mac, the arrival of an unlikely pop star. Kate Bush had an of Pink Floyd guitarist David Gilmour thanks to ran from relatively unadorned piano-led art-rock the Eagles, the Doobie Brothers, Chic.) Kate didn’t unusually high and wide-ranging voice, a curious family friends with connections to the band. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Berköz, Levent Donat (2012). A gendered musicological study of the work of four leading female singer-songwriters: Laura Nyro, Joni Mitchell, Kate Bush, and Tori Amos. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1235/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] A Gendered Musicological Study of the Work of Four Leading Female Singer-Songwriters: Laura Nyro, Joni Mitchell, Kate Bush, and Tori Amos Levent Donat Berköz Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy City University London Centre for Music Studies June 2012 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ………………………………………………………… 2 LIST OF FIGURES ……………………………………………………………… 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ……………………………………………………… 7 DECLARATION ………………………………………………………………… 9 ABSTRACT ……………………………………………………………………… 10 INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………….. 11 Aim of the thesis…………………………………………………………………. -

“Into the Sensual World”: Gender Subversion in the Work of Kate Bush

“Into the Sensual World”: Gender Subversion in the Work of Kate Bush BA Thesis English Literature Supervisor: Dr U. Wilbers Semester 2 image: Sarah Neutkens, 2019 Severens 1 Engelse Taal en Cultuur Teacher who will receive this document: Dr Usha Wilbers Title of document: “Into the Sensual World”: Gender Subversion in the Work of Kate Bush Name of course: BA Thesis Course Date of submission: 14–06–2019 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed: Name of student: Student number: Severens 2 Abstract Kate Bush remains one of the most successful and original British female music artists and is often perceived as a female pioneer. This thesis analyses a selection of her earlier work in order to establish how she represents issues of gender and sexuality in her lyrics and performances. Her work is evaluated through the lens of two feminist theories: écriture feminine and gender performativity. Écriture féminine is employed to determine how Bush writes and reclaims female sexuality, while gender performativity subsequently shows how she transcends her position as a woman by taking on and representing characters of the opposite gender. This thesis argues that Bush constructs narratives in her lyrics to represent experiences which transcend the boundaries of binary gender and challenge social sexual norms. Keywords: Kate Bush, gender performativity, écriture féminine, song lyrics, popular music studies Severens 3 Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 1. Theoretical Framework ................................................................................................... 8 2. Stepping Out Of The Page: Kate Bush Writing Women .............................................. 16 3. -

Kate Bush Essay 1

Evaluate the use of forces, structure and tonality in ‘Hounds of Love’ by Kate Bush Kate Bush is a British singer and composer who released the album ‘Hounds of Love’ in 1985. The style which she sang and wrote music was very unique and avant-garde, providing a distinctive concept with her music compared to other musicians around the same time. Most of Kate’s works were inspired by novels and historical sources as well as being influenced by genres such as folk, electronic and classical music which allowed her to create something diverse. In this essay, I will be exploring the ways that Kate Bush created the unique style that she was known for by evaluating the uses of instrumentation, structure and tonality in the songs ‘Cloud busting’, ‘And Dream of Sheep’ and ‘Under Ice’ t o understand how she achieved a sense of individuality and broke new ground. One of the most prominent features of Kate Bush’s works was the choice of instrumentation that she used. Instead of focusing on the standard pop instrumentation, she experimented with new technological advances and also instruments associated with different genres and styles. In the song ‘Cloudbusting’, a string sextet provides the main accompaniment and was not considered as a typical instrument in the pop genre, this was due mainly due to its inability to be performed live. Another example of a song which uses strings as a main accompaniment is ‘Eleanor Rigby’ by the Beatles, who were also know to have broken new ground due to their instrumentation choices which were not able to support a live performance. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Kate Bush Hounds of Love / Never for Ever Mp3, Flac, Wma

Kate Bush Hounds Of Love / Never For Ever mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Hounds Of Love / Never For Ever Country: France Released: 2006 Style: Art Rock, Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1563 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1107 mb WMA version RAR size: 1620 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 436 Other Formats: ADX VOC TTA DXD MPC AU AAC Tracklist Hounds Of Love 1-1 Running Up That Hill (A Deal With God) 1-2 Hounds Of Love 1-3 The Big Sky 1-4 Mother Stands For Comfort 1-5 Cloudbusting The Ninth Wave 1-6 And Dream Of Sheep 1-7 Under Ice 1-8 Waking The Witch 1-9 Watching You Without Me 1-10 Jig Of Life 1-11 Hello Earth 1-12 The Morning Fog Bonus Tracks 1-13 The Big Sky (MeTeorological Mix) 1-14 Running Up That Hill (12" Mix) 1-15 Be Kind To My Mistakes 1-16 Under The Ivy 1-17 Burning Bridge 1-18 My Lagan Love Never For Ever 2-1 Babooshka 2-2 Delius 2-3 Blow Away (For Bill) 2-4 All We Ever Look For 2-5 Egypt 2-6 The Wedding List 2-7 Violin 2-8 The Infant Kiss 2-9 Night Scented Stock 2-10 Army Dreamers 2-11 Breathing Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Novercia Ltd. Phonographic Copyright (p) – EMI Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – EMI Music France Licensed To – EMI Records Ltd. Marketed By – EMI Distributed By – EMI Notes 2 CDs in a card slipcase featuring the 1997 extended reissue of Hounds Of Love and a standard repress of Never For Ever. -

Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM

Another Protest Song: Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM a project of Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere for SOMA Summer 2019 at La Morenita Canta Bar (Puente de la Morena 50, 11870 Ciudad de México, MX) karaoke provided by La Morenita Canta Bar songbook edited by Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere ( ) 18840 (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash 10274 (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & Diamonds 00005 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 17636 (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 15910 (I Want To) Thank You Freddie Jackson 05545 (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees 06305 (It's) A Beautiful Mornin' Rascals 19116 (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon 15128 (Keep Feeling) Fascination Human League 04132 (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran 05241 (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding 17305 (Taking My) Life Away Default 15437 (Who Says) You Can't Have It All Alan Jackson # 07630 18 'til I Die Bryan Adams 20759 1994 Jason Aldean 03370 1999 Prince 07147 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer 18961 21 Guns Green Day 004-m 21st Century Digital Boy Bad Religion 08057 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 00714 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band 01379 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 14375 3 Strange Days School Of Fish 08711 4 Minutes Madonna 08867 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 09981 4 Minutes Avant 18883 5 Miles To Empty Brownstone 13317 500 Miles Peter Paul & Mary 00082 59th Street Bridge Song Simon & Garfunkel 00384 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 08937 99 Luftballons Nena 03637 99 Problems Jay-Z 03855 99 Red Balloons Nena 22405 1-800-273-8255