The Lost Mysteries of New Orleans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nelda Reyes-Resume Ryanartists

Nelda Reyes SAG/AFTRA Hair: Dark brown Eyes: Brown Height: 5” 3’ TV/FILM “Not one more” Isabel Heather Dominguez dir./Art Institute of Portland Grimm - Episode # 111 “Tarantella” Maid Peter Werner /NBC COMMERCIAL/INDUSTRIAL *Complete list available upon request “OCDC Spanish & English PSA” Nelda Reyes Rex-post “SEIU Orientation and Safety Video” HCA Branch Ave. Productions “Wired MD Patient Educational Videos” Health Expert Krames Video Solutions “American Red Cross EMR” Health Officer Erica Portfolio Productions “Depression Relapse”-ORCAS Carmen Moving Images VOICEOVER AND DUBBING *Complete list available upon request “Kaiser Permanente Diabetes Bilingual Campaign” Patti The Fotonovela Production Company “Abuelo -Ac tive Living” -Multnomah County Health Univision Portland Mom Department. “CISCO Online Support website ” Narrator Intersect Video THEATER *Complete list available upon request CORRIDO CALAVERA Concepcion, INC Rep, Rosario Miracle Theatre Group/Lakin Valdez dir. DANCE FOR A DOLLAR Gloria Miracle Theatre Group/Daniel Jaquez dir. BLOOD WEDDING Criada, Luna, Niña 1 Miracle Theatre Group/Olga Sanchez dir LA CARPA CALAVERA Nina Miracle Theatre Group/Philip Cuomo dir. ACTING AND MOVEMENT TRAINING Acting, Scene Work and Movement Moscow Art Theatre School and IATT, Harvard University M. Lovanov/ Alla Prokoskaya/ Oleg Topolyanskiy /N. Fedorovna Acting: Process, Classical, Experimental styles Devon Allen. Portland State University. MA. In Theatre Arts Script Analysis and Dramaturgy Karin Magaldi. Portland State University. MA. In Theatre Arts Clown Fausto Ramirez (Mexico) and Les Matapestes (France) Alexander, Decroux, Lecoq, Contact Improv. Diplomado de Teatro del Cuerpo (Mexico City) Diploma for Instructors in Kundalini Yoga IKYTA/ Yoga Alliance Empty Hand Combat and basic weaponry Anthony De Longis (USA) Shelley Lipkin Acting for the Camera (USA) Professional Training in Aerial Arts The Circus Project (US A) Pre-professional Classic Dance Program Ballet Nacional de Cuba/Gloria Campobello Co. -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

An Interview with John Jakes, Chronicler of the American Epic

Civil War Book Review Spring 2000 Article 1 'Unrelenting Suspense': An Interview With John Jakes, Chronicler Of The American Epic Katie L. Theriot Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Theriot, Katie L. (2000) "'Unrelenting Suspense': An Interview With John Jakes, Chronicler Of The American Epic," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol2/iss2/1 Theriot: 'Unrelenting Suspense': An Interview With John Jakes, Chronicler Interview 'UNRELENTING SUSPENSE': AN INTERVIEW WITH JOHN JAKES, CHRONICLER OF THE AMERICAN EPIC Theriot, Katie L. Spring 2000 Civil War Book Review (cwbr): You have achieved prominence as a writer of historical fiction. Do you see your role as primarily literary or historical -- or both? John Jakes (jj): From the time I made my first sale (a 1500-word short story in 1950), writing an entertaining narrative was my chief goal. It was, that is, until the 1970s, when I began to research and write the first of The Kent Family Chronicles. At that point something new intruded: before starting to write the first volume, The Bastard (Jove, ISBN 0515099279, $7.99 softcover), I decided to think of the novels as perhaps the only books about a given period that someone might read. The history therefore had to be as correct as conscientious research could make it without devoting a lifetime to it. I have followed that path ever since, with two goals for every novel: the entertaining story and the accurate history. Readers have come to appreciate and expect that duality, and indeed some have said that people have probably learned more history from me than from all the teachers, texts, and scholarly tomes in existence. -

Women's Club Arranges Fall Decorations on Front Street

INSIDE TODAY: Agency eyes big revamp of Wall Street whistleblower program /A3 OCT. 13, 2019 JASPER, ALABAMA — SUNDAY — www.mountaineagle.com $1.50 INSIDE MANY ATTEND DAY’S GAP FESTIVAL IN OAKMAN Parade of pets takes over park Local furbabies dressed in their best took over Gamble Park on Saturday. /A10 BRIEFS Army defends decision to close space, Daily Mountain Eagle - Nicole Smith tech library The streets of Oakman were crowded for the HUNTSVILLE, Ala. Day’s Gap Festival on Friday and Saturday. Vis- (AP) — The U.S. itors enjoyed the fall temperature while brows- Army is defending a ing vendor booths and enjoying music, games, decision to close its food, and a car show. This was the third year for historic 57-year-old Oakman to host Day’s Gap Fest, which invites space and technical Oakman natives to celebrate their hometown. library at Redstone Arsenal. Army officials said it was a joint decision made by Grinston to be at Jasper interested parties. The Redstone Veterans Day Parade Scientific Infor- mation Center, or By ED HOWELL RSIC, closed its Daily Mountain Eagle doors Sept. 30, Sgt. Maj. of the Army Michael A. Grinston, who grew up in Jasper, will be the grand marshal of this Al.com reported. year’s Jasper Veterans Day Parade, resulting in the 11 a.m. parade being moved to Monday, Nov. 11, DEATHS and requirements for signing up in advance to participate in the event. The parade has traditionally Wanda Dean Jackson, 66, been held on Saturday mornings, Sheffield but Grinston was not available Reba Shubert Morrow, 87, Hueytown until later “so we made the parade work for him in his schedule,” co-or- ganizer Brent McCarver said. -

Complete Issue

_____________________________________________________________ Volume 8 October 1993 Number 2 _____________________________________________________________ Editor Editorial Assistants John Miles Foley Dave Henderson Elizabeth P. McNulty Catherine S. Quick Slavica Publishers, Inc. For a complete catalog of books from Slavica, with prices and ordering information, write to: Slavica Publishers, Inc. P.O. Box 14388 Columbus, Ohio 43214 ISSN: 0883-5365 Each contribution copyright (c) 1993 by its author. All rights reserved. The editor and the publisher assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion by the authors. Oral Tradition seeks to provide a comparative and interdisciplinary focus for studies in oral literature and related fields by publishing research and scholarship on the creation, transmission, and interpretation of all forms of oral traditional expression. As well as essays treating certifiably oral traditions, OT presents investigations of the relationships between oral and written traditions, as well as brief accounts of important fieldwork, a Symposium section (in which scholars may reply at some length to prior essays), review articles, occasional transcriptions and translations of oral texts, a digest of work in progress, and a regular column for notices of conferences and other matters of interest. In addition, occasional issues will include an ongoing annotated bibliography of relevant research and the annual Albert Lord and Milman Parry Lectures on Oral Tradition. OT welcomes contributions on all oral literatures, on all literatures directly influenced by oral traditions, and on non-literary oral traditions. Submissions must follow the list-of reference format (style sheet available on request) and must be accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope for return or for mailing of proofs; all quotations of primary materials must be made in the original language(s) with following English translations. -

Der Räuber Schinderhannes Der Gebreitet

Als Burkhard zum letzten Male den Pflug wendet, steigt gegenüber, da wo ERICH BRAUTLACHT: morgens über dem walde die sonne aufgegangen war,.der Mond aus einer grauän Wand, unglaubhaft groß und klar. Eine verrvirrende Lictrtfülle liegt über die Fel- Der Räuber Schinderhannes der gebreitet. Er fühlt sidr plötzlidr mit der Erde emporgehoben und im umkreis der welten und Gestirne allein auf dieser Erde. Er, der pflüger, dem siclr die Erde unterwirft, er: Bebauer, Zeuger und Ernährer, Mittelpunkt der welt von Anbeginn! Im Jahre 1734 gab der französische Rechtsanwalt Pitaval den ersten verschwistert mit Scholle, Baum und Strauch, mit allen Erd- und Himmels- Band seiner Sammlung ,,Berühmte und interessante Strafprozesse" heraus. geistern, denen der Mensch der Städte sich längst entfremdet hat, - so sieht er"' Spätere Herausgeber setzten diese Arbeit fort, so daß zu Ende des 19. Jahr- sich vor. das Angesidrt des schöpfers gehoben. Jenseits alter Händel der Men. hunderts die Sammlung des ,,Neuen Pitaval" 60 Bände umfaßte. Friedrictr Schiller nannte.im Jahre 1?92 die von ihm besorgte neue Aus- schen, jenseits aller Nationen, fühlt er sich vor das glühende Schöpferauge gestellt.l gabe des Pitaval einen ,,Beitrag zur Geschichte der Menschheit", In seinem sein Tagewerk wird zum heiligen Dienst, großen zur Feier vor dem Ewigen, unfaß- Vorwort zu dieser Ausgabe heißt es: ,,Man findet darin eine Auswahl gericttt- baren. Der Acker unter ihm weitet sich zur Welt. IJnd die Geister der Ahnen, die licher FäIle, welctre sich an Interesse der Handlung, an künstlerischer Ver- hier vor ihm gepflügt, von Jahihundert zu Jahrhundert, gehen mit ihm durctr die wicklung und Mannigfaltigkeit der Gegenstände bis zum Roman erheben. -

Scholastic, Inc. Ready-To-Go Complete Title Lists 2015 1

Scholastic, Inc. Ready-To-Go Complete Title Lists 2015 2015 2015 List Customer AR AR Item # Collection Name # Books Price Price Title Author F/NF Lexile GRL DRA SRC Quiz Quiz Level 969936 Ready-To-Go Classroom Library, 300 Books $1,608.51 $995.00 970432 Ready-To-Go: Favorites, Kindergarten (100 Books) F Kindergarten 970433 Ready-To-Go: Independent Reading, Kindergarten (100 Books) F 970434 Ready-To-Go: Nonfiction, Kindergarten (100 Books) F 970432 Ready-To-Go: Favorites, Kindergarten 100 Books $595.60 $379.00 Abuela Arthur Dorros F 510 L 20-24 Q00075 17501 2.5 Alice the Fairy David Shannon F 510 K 16-18 Q36205 83029 2.5 All About You Catherine & Laurence Anholt F 60 G 12 Q00227 31550 4.5 Alphabet Adventure Audrey Wood F 410 I 16 Q25398 84203 3.3 Bear Shadow Frank Asch F 580 J 16-18 Q00985 45442 2.8 Bearobics Vic Parker F 570 Q26505 Beatrice Doesn't Want To Laura Numeroff F 140 J 16-18 Q35883 82078 2.2 Big Red Barn Margaret Wise Brown F 640 H 14 Q01221 29469 2.4 Biggest Pumpkin Ever, The Steven Kroll F 570 M 20-24 Q01240 11160 3.5 Biggest Valentine Ever, The Steven Kroll F 610 J 16-18 Q38412 105025 3 Blueberries for Sal Robert McCloskey F 890 M 20-24 Q01385 5459 4.1 Building a House Byron Barton NF 100 H 14 Q24911 Caps, Hats, Socks, and Mittens Louise W. Borden F 240 H 14 Q01817 Cat and a Dog / Un gato y un perro, A Claire Masurel F Chicka Chicka Boom Boom John Archambault F 530 L 20-24 Q02091 Clap Your Hands Lorinda Bryan Cauley F 410 H 14 Q02254 Clifford the Big Red Dog Norman Bridwell F 220 K 16-18 Q02343 6059 1.2 Clifford® Clifford's Field Day Norman Bridwell F 250 I 16 Q53270 150009 1.2 Color of His Own, A Leo Lionni F 640 F 10 Q02398 49248 2.3 Cookie's Week Cindy Ward F 100 F 10 Q02491 117080 1.3 Curious George Rides a Bike H. -

Orality in Medieval Drama Speech-Like Features in the Middle English Comic Mystery Plays

Dissertation zur Erlangung des philosophischen Doktorgrades Orality in Medieval Drama Speech-Like Features in the Middle English Comic Mystery Plays vorgelegt von Christiane Einmahl an der Fakultät Sprach-, Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaften der Technischen Universität Dresden am 16. Mai 2019 Table of Contents 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Premises and aims ................................................................................................................2 1.2 Outline of the study .............................................................................................................10 2 Comedy play texts as a speech-related genre ........................................................................13 2.1 Speech-like genres and 'communicative immediacy'...........................................................13 2.2 Play texts vs. 'real' spoken discourse...................................................................................17 2.3 Conclusions.........................................................................................................................25 3 'Comedy' in the mystery cycles................................................................................................26 3.1 The medieval sense of 'comedy'..........................................................................................26 3.2 Medieval attitudes to laughter..............................................................................................37 -

Kostbares Wasser

Wasser Stand September 2011 Thema 5 Kostbares Hahnenbach Kellenbach Bach bei Seesbach Hahnenbach Als um 1900 in der Region verstärkt Typhusfälle auftraten, bauten Weitere Informationen zum Naturpark Soonwald-Nahe und zu den entlang Einrichtungen erhalten Sie hier: Trinkwassergewinnung viele Gemeinden ihre ersten zentralen Wasserversorgungsanlagen. des Natur-Erlebnisweges Schinderhannes Als Beispiel aus dem Jahre 1907 ist an der Wegstrecke noch der Trägerverein Naturpark Naturpark Naturpark Soonwald-Nahe e.V. SOONWALD-NAHE alte Hochbehälter der Gemeinde Mengerschied zu sehen, der Ludwigstraße 3-5 SOONWALD-NAHE Am Nordrand des Soonwaldes verläuft der Natur-Erlebnisweg jedoch durch neuere Wasserversorgungsanlagen seine Funktion 55469 Simmern Schinderhannes. Entlang dieses Weges sind Quellen, Brunnen [email protected] verloren hat. www.soonwald-nahe.de und Wasseraufbereitungsanlagen zu finden, aus denen unser Trinkwasser geliefert wird. Hunsrück-Touristik GmbH Naheland-Touristik GmbH Gebäude 663 Bahnhofstraße 37 Um das kostbare Grundwasser vor dem Eintrag von Schadstoffen Trinkwassergewinnung 55483 Hahn-Flughafen 55606 Kirn/Nahe durch Tiefbrunnen zu schützen, wurden Wasserschutzgebiete ausgewiesen, die je [email protected] [email protected] www.hunsruecktouristik.de www.naheland.net Trinkwassergewinnung nach Schutzgrad in die Zonen I bis III unterteilt werden. Zone I entlang des schützt den direkten Bereich um die jeweilige Fassung (Brunnen) und ist durch Zaunanlagen geschützt. Schluf f Diese Publikation wurde im Rahmen des Entwicklungsprogramms -

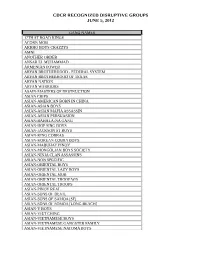

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

Mitteilungsblatt

Mitteilungsblatt Ortsgemeinden: Bretzenheim, Dorsheim, Guldental, Langenlonsheim, Laubenheim, Rümmelsheim, Windesheim Mitteilungen & Informationen Jahrgang 50 Nummer 40 Freitag, 05.10.2018 Verleihung des Umweltpreises 2017 der Verbandsgemeinde Langenlonsheim Bürgermeister Michael Cyfka überreicht die Urkunden an den Vertreter der Grundschule Langenlonsheim und die Vertreter des NABU Bad Kreuznach. Am 20.09.2018 wurde der Umweltpreis der Verbandsgemeinde Langenlonsheim für das Jahr 2017 verliehen. Vom NABU sind drei Projekte für den Umweltpreis genannt: Die Grundschule Langenlonsheim hat folgende Projekte genannt: 1. Seit 2006 wurden im Kreis Bad Kreuznach 140 Steinkauzröhren instal- 1. Seit 2010 nimmt die Schule am „Tag der Artenvielfalt“ teil, was dazu liert, davon 18 in der Verbandsgemeinde Langenlonsheim. In diesen sind führte, 2015 eine Schulimkerei einzurichten. Zur Zeit verfügt die Schule seither rund 65 Bruten mit 212 Jungvögeln erfolgt. über ein Bienenvolk. Alle Arbeiten zur Pflege der Bienenstöcke, der Schaf- fung der Voraussetzungen zur Vermehrung der Bienenvölker bis zur Honi- 2. Seit über 20 Jahren werden im Langenlonsheimer Wald ca. 100 Nist- gernte werden von ihm und den Schülern übernommen. Der Erlös aus kästen betreut, in denen verschiedene Vogel- und Fledermausarten, aber dem Verkauf des Honigs, im letzten Jahr waren dies ca. 25 kg, geht in auch Schläferarten Brut- und Aufzuchtmöglichkeiten finden. voller Höhe an den Förderverein der Schule. 3. Seit Jahren werden vom NABU regelmäßig Landschaftspflegearbeiten, 2. In Zusammenarbeit mit dem NABU wurden Fledermauskästen aufge- hier insbesondere in der Gemarkung Laubenheim in den Gebieten hängt sowie im Rahmen der Projekttage ein „Insektenhotel“ errichtet. „Scheerwald“ und „Sponsheimer Berg“ durchgeführt, um die dortigen 3. Auf der alten Laufbahn an der Schule wurden Hochbeete errichtet und wertvollen Biotopstrukturen zu erhalten.