Orality in Medieval Drama Speech-Like Features in the Middle English Comic Mystery Plays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tikrit University College of Education for Humanities English Department First Year 2019-2020

Tikrit University College of Education for Humanities English Department First year 2019-2020 Medieval Theatre Assist. Prof. Marwa Sami Hussein Medieval Theatre Medieval times started after the fall of Rome and lasted through to 15th century, roughly to the Protestant Reformation. In this time before the printing press made it necessary or even possible for the great majority of people to read, the primary method of teaching and learning was through the oral tradition. Throughout this time, the church had grown to become the most powerful and most consistent institution throughout Europe. Since theatre tells stories, it was a natural mechanism for telling the bible stories and delivering any other information the church wanted communicated to the people, particularly as this period was a time of turmoil (chaos) and the church was the only stable government. In fact, the church had become so strong that it was able to close all theatre productions except for those that it officially sanctioned (acceptable). Those plays fell into three categories: morality, mystery and miracle plays. 1-Mystery play Mystery play: is a dramatic genre, one of three principal kinds of vernacular (colloquial) drama in Europe during the Middle Ages (along with the miracle play and the morality play). The mystery plays, usually representing biblical subjects, developed from plays presented in Latin by churchmen on church premises (building) and depicted such subjects as the Creation, Adam and Eve, the murder of Abel, and the Last Judgment. 1 During the 13th century, various guilds began producing the plays in the vernacular at sites removed from the churches. -

Complete Issue

_____________________________________________________________ Volume 8 October 1993 Number 2 _____________________________________________________________ Editor Editorial Assistants John Miles Foley Dave Henderson Elizabeth P. McNulty Catherine S. Quick Slavica Publishers, Inc. For a complete catalog of books from Slavica, with prices and ordering information, write to: Slavica Publishers, Inc. P.O. Box 14388 Columbus, Ohio 43214 ISSN: 0883-5365 Each contribution copyright (c) 1993 by its author. All rights reserved. The editor and the publisher assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion by the authors. Oral Tradition seeks to provide a comparative and interdisciplinary focus for studies in oral literature and related fields by publishing research and scholarship on the creation, transmission, and interpretation of all forms of oral traditional expression. As well as essays treating certifiably oral traditions, OT presents investigations of the relationships between oral and written traditions, as well as brief accounts of important fieldwork, a Symposium section (in which scholars may reply at some length to prior essays), review articles, occasional transcriptions and translations of oral texts, a digest of work in progress, and a regular column for notices of conferences and other matters of interest. In addition, occasional issues will include an ongoing annotated bibliography of relevant research and the annual Albert Lord and Milman Parry Lectures on Oral Tradition. OT welcomes contributions on all oral literatures, on all literatures directly influenced by oral traditions, and on non-literary oral traditions. Submissions must follow the list-of reference format (style sheet available on request) and must be accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope for return or for mailing of proofs; all quotations of primary materials must be made in the original language(s) with following English translations. -

History of Theatre the Romans Continued Theatrical Thegreek AD (753 Roman Theatre fi Colosseum Inrome, Which Was Built Between Tradition

History of theatre Ancient Greek theatre Medieval theatre (1000BC–146BC) (900s–1500s) The Ancient Greeks created After the Romans left Britain, theatre purpose-built theatres all but died out. It was reintroduced called amphitheatres. during the 10th century in the form Amphitheatres were usually of religious dramas, plays with morals cut into a hillside, with Roman theatre and ‘mystery’ plays performed in tiered seating surrounding (753BC–AD476) churches, and later outdoors. At a the stage in a semi-circle. time when church services were Most plays were based The Romans continued the Greek theatrical tradition. Their theatres resembled Greek conducted in Latin, plays were on myths and legends, designed to teach Christian stories and often involved a amphitheatres but were built on their own foundations and often enclosed on all sides. The and messages to people who could ‘chorus’ who commented not read. on the action. Actors Colosseum in Rome, which was built between wore masks and used AD72 and AD80, is an example of a traditional grandiose gestures. The Roman theatre. Theatrical events were huge works of famous Greek spectacles and could involve acrobatics, dancing, playwrights, such as fi ghting or a person or animal being killed on Sophocles, Aristophanes stage. Roman actors wore specifi c costumes to and Euripedes, are still represent different types of familiar characters. performed today. WORDS © CHRISTINA BAKER; ILLUSTRATIONS © ROGER WARHAM 2008 PHOTOCOPIABLE 1 www.scholastic.co.uk/junioredplus DECEMBER 2008 Commedia dell’Arte Kabuki theatre (1500s Italy) (1600s –today Japan) Japanese kabuki theatre is famous This form of Italian theatre became for its elaborate costumes and popular in the 16th and 17th centuries. -

History of Greek Theatre

HISTORY OF GREEK THEATRE Several hundred years before the birth of Christ, a theatre flourished, which to you and I would seem strange, but, had it not been for this Grecian Theatre, we would not have our tradition-rich, living theatre today. The ancient Greek theatre marks the First Golden Age of Theatre. GREEK AMPHITHEATRE- carved from a hillside, and seating thousands, it faced a circle, called orchestra (acting area) marked out on the ground. In the center of the circle was an altar (thymele), on which a ritualistic goat was sacrificed (tragos- where the word tragedy comes from), signifying the start of the Dionysian festival. - across the circle from the audience was a changing house called a skene. From this comes our present day term, scene. This skene can also be used to represent a temple or home of a ruler. (sometime in the middle of the 5th century BC) DIONYSIAN FESTIVAL- (named after Dionysis, god of wine and fertility) This festival, held in the Spring, was a procession of singers and musicians performing a combination of worship and musical revue inside the circle. **Women were not allowed to act. Men played these parts wearing masks. **There was also no set scenery. A- In time, the tradition was refined as poets and other Greek states composed plays recounting the deeds of the gods or heroes. B- As the form and content of the drama became more elaborate, so did the physical theatre itself. 1- The skene grow in size- actors could change costumes and robes to assume new roles or indicate a change in the same character’s mood. -

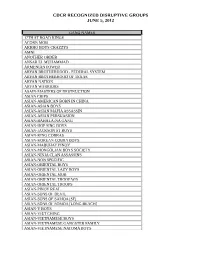

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

The Staging of the Theatrical Corpse in Early Modern Drama

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Fall 2010 Corpses revealed: The staging of the theatrical corpse in early modern drama N M. Imbracsio University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Imbracsio, N M., "Corpses revealed: The staging of the theatrical corpse in early modern drama" (2010). Doctoral Dissertations. 520. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/520 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CORPSES REVEALED: THE STAGING OF THE THEATRICAL CORPSE IN EARLY MODERN DRAMA BY N. M. IMBRACSIO Baccalaureate of Arts, Clark University, 1 998 Master of Arts, University of Massachusetts-Boston, 2001 Master of Fine Arts, Emerson College, 2004 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English September, 2010 UMI Number: 3430774 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3430774 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. -

Glendale Police Department

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ClPY O!.F qL'J;9{'jJ.!JL[/E • Police 'Department 'Davit! J. tJ1iompson CfUt! of Police J.1s preparea 6y tfit. (jang Investigation Unit -. '. • 148396 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been g~Qted bY l' . Giend a e C1ty Po11ce Department • to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyright owner. • TABLEOFCON1ENTS • DEFINITION OF A GANG 1 OVERVIEW 1 JUVENILE PROBLEMS/GANGS 3 Summary 3 Ages 6 Location of Gangs 7 Weapons Used 7 What Ethnic Groups 7 Asian Gangs 8 Chinese Gangs 8 Filipino Gangs 10 Korean Gangs 1 1 Indochinese Gangs 12 Black Gangs 12 Hispanic Gangs 13 Prison Gang Influence 14 What do Gangs do 1 8 Graffiti 19 • Tattoo',;; 19 Monikers 20 Weapons 21 Officer's Safety 21 Vehicles 21 Attitudes 21 Gang Slang 22 Hand Signals 22 PROFILE 22 Appearance 22 Headgear 22 Watchcap 22 Sweatband 23 Hat 23 Shirts 23 PencHetons 23 Undershirt 23 T-Shirt 23 • Pants 23 ------- ------------------------ Khaki pants 23 Blue Jeans 23 .• ' Shoes 23 COMMON FILIPINO GANG DRESS 24 COMMON ARMENIAN GANG DRESS 25 COrvtMON BLACK GANG DRESS 26 COMMON mSPANIC GANG DRESS 27 ASIAN GANGS 28 Expansion of the Asian Community 28 Characteristics of Asian Gangs 28 Methods of Operations 29 Recruitment 30 Gang vs Gang 3 1 OVERVIEW OF ASIAN COMMUNITIES 3 1 Narrative of Asian Communities 3 1 Potential for Violence 32 • VIETNAMESE COMMUNITY 33 Background 33 Population 33 Jobs 34 Politics 34 Crimes 34 Hangouts 35 Mobility 35 Gang Identification 35 VIETNAMESE YOUTH GANGS 39 Tattoo 40 Vietnamese Background 40 Crimes 40 M.O. -

Medieval Drama Teaches the Spectators What They Already Know; It Therefore Lacks Excitement, Surprise and Alienation.” Discuss, with Reference to the Morality Plays

Alistair Welch for Katie Walter Girton College King’s College, 558 “Medieval drama teaches the spectators what they already know; it therefore lacks excitement, surprise and alienation.” Discuss, with reference to the morality plays. There appears to be some critical debate concerning the number of extant morality plays available to the modern reader. Pamela M. King asserts authoritatively: “only five medieval English morality plays survive”1, whereas Robert Potter suggests a number close to twenty2. However, this essay deals with the three examples published in the New Mermaid3 edition edited by G.A Lester, namely Mankind, Everyman and Mundus et Infans. As such my reading is admittedly confined to a selection of texts canonically recognised and consciously labelled as examples of morality play. If such a dull opening paragraph has a purpose it is to suggest that the very definition of a text as a morality play is problematic. It suggests that the plays operate as a coherent group and, more significantly, encourages a reading of the texts within the received limitations of their genre. The OED defines morality play as follows: “morality play now chiefly hist., a kind of drama popular in the 15th and early 16th centuries, intended to inculcate a moral or spiritual lesson, in which the chief character are personifications of abstract qualities.” So, according to the OED, morality play as a genre is tied to a notion of teaching and moralizing through stock allegorical technique. By definition, therefore, its dramatic potential might be understood to be limited. Indeed, the terms of the question and the OED’s definition might appear to be corroborated by the closing speeches, essentially the epilogues, of Mankind and Everyman: “Thynke and remembyr the world ys but a wanite As yt ys prowyd daly by diverse transmutacyon.” (Mankind, 908-09) “Ye hearers take it of worth olde and yonge. -

The Origin of the European Mediaeval Drama

International Journal of Scientific Research and Innovative Technology ISSN: 2313-3759 Vol. 3 No. 1; January 2016 The Origin of the European Mediaeval Drama P. Wijith Rohan Fernando Department of Western Classical Culture and Christian Culture University of Kelaniya Sri Lanka Historical Background The starting point of drama is religion.1 The root of the modern drama is based on the ritualistic resources of primitive religions. “Such is the case of the notion of ‘ritual drama’, the idea that serious drama is historically grounded in sacred ritual and may still draw on ritualistic resources for its substance.”2 The ritualistic character of religion is found not only in Greek theatre but in the dramas of other countries as well. “Scholars had long known and accepted the Greek theatre (and analogous traditions in Mediaeval and Renaissance Europe, Japan, China, and India) had roots in religion and ritual. Aristotle and other commentators had canonized that fact. Indeed Aristotle’s classic statements from the Poetics – that tragedy originated from the leader of the sacred (presumably Dionysian) dithyramb ritual and comedy from the leader of the phallic processions – provided the starting point for every study of the origins of drama.”3 Thus, the origin of the modern theatre goes back as far as the Greek ritual plays centred on the altar of Dionysus, the wine-god and the god of fertility and procreation, around 1200 BC.4 The chant or the hymn that was sung in praise of god Dionysius is known as Dithyramb. It is a choric hymn which is considered as the root of Greek drama.5 It was Thespis who introduced an actor (Protagonist) in the Dithyramb around 594 BC.6 With Thespis thus began the classical Greek drama. -

1 Medieval and Renaissance Drama Society Newsletter Spring 2018 A

Medieval and Renaissance Drama Society Newsletter Spring 2018 rd a The 53 Congress on Medieval Studies b May 9-13, 2018 MRDS Sponsored Sessions Approaches to Teaching Medieval Drama, Revisited Claire Sponsler: In Memoriam I Session 103, Thursday 3:30, Fetzer 1045 Session 287, Friday 3:30, Fetzer 2016 Organizer: Frank Napolitano, Radford Univ. Organizer: Matthew Evan Davis, McMaster Univ. Presider: Andrew M. Pfrenger, Kent State Univ.–Salem Presider: Matthew Evan Davis Authentic Pedagogy in the Medieval Drama Classroom Crossdressing on the Medieval Stage: A Transgender and Cameron Hunt McNabb, Southeastern Univ. Transracial Sartorial Masquerade The Umpteenth Annual Secunda Pastorum at a Commuter Jesse Njus, Virginia Commonwealth Univ. Campus, or, My Son, the Stolen Sheep Medieval Drama and the “Myth of Communal Life” in the Betsy Bowden, Rutgers Univ. Twenty-First Century Countering Presentism in a Student-Led Performance of Heather Mitchell-Buck, Hood College Mankind Hamilton and Medieval Drama Boyda J. Johnstone, Fordham Univ. Michelle Markey Butler, Univ. of Maryland Not Scripted: Playing with the Archive Gina Di Salvo, Univ. of Tennessee–Knoxville Staging Politics: Tyranny, Repression, and Unrest in Medieval and Renaissance Drama Society Medieval Plays Executive Council Meeting Session 161, Friday 10:00, Valley 3 Eldridge 309 Friday 11:45 a.m. Organizer: Mario B. Longtin, Western Univ. Fetzer 1030 Presider: Mario B. Longtin Medieval and Renaissance Drama Society Tyrannicide, Liberation, and Proto-Reformation Preaching in Business Meeting the Earliest Extant William Tell Play (ca. 1512) Friday 5:15 Stephen K. Wright, Catholic Univ. of America Fetzer 2016 That Reverant Unutile Moi Play: Herod’s Gibberish Ruth Nisse, Wesleyan Univ. -

Medieval Theatre Miracle Play

Medieval Theatre Miracle Play SAINT NICHOLAS (A.K.A. SANTA CLAUS) The true story of Santa Claus begins with Nicholas, who was born during the third century in Patara, a village in what is now Turkey. His wealthy parents, who raised him to be a devout Christian, died in an epidemic while Nicholas was still young. Obeying Jesus' words to "sell what you own and give the money to the poor," Nicholas used his whole inheritance to assist the needy, the sick, and the suffering. He dedicated his life to serving God and was made Bishop of Myra while still a young man. Bishop Nicholas became known throughout the land for his generosity to those in need, his love for children, and his concern for sailors and ships. Under the Roman Emperor Diocletian, who ruthlessly persecuted Christians, Bishop Nicholas suffered for his faith, was exiled and imprisoned. The prisons were so full of bishops, priests, and deacons, there was no room for the real criminalsmurderers, thieves and robbers. After his release, Nicholas attended the Council of Nicaea in AD 325. He died December 6, AD 343 in Myra and was buried in his cathedral church, where a unique relic, called manna, formed in his grave. This liquid substance was said to have healing powers which fostered the growth of devotion to Nicholas. The anniversary of his death became a day of celebration, St. Nicholas Day. Through the centuries many stories and legends have been told of St. Nicholas' life and deeds. These accounts help us understand his extraordinary character and why he is so beloved and revered as protector and helper of those in need. -

Why Scholars of Medieval Theatre Should Be Historians

Proposal Narrative Toward a New History of Medieval Theatre: Assessing the Written and Unwritten Evidence for Indigenous Performance Practices Carol Symes Department of History, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Société Internationale pour l’étude du Théâtre Médiéval XIIe Congrès – Lille, 2-7 juillet 2007 A B S T R A C T “Medieval drama” is essentially an invention of modern philology, which drew upon the models of classical literature, evolutionary biology, ethnography, and nationalism for its constructions of the medieval past. Access to a truly medieval theatre, therefore, requires us to eschew these expectations and categories, which still govern the study of formal dramatic documents and the larger culture which produced them, and to look very freshly at the evidence for indigenous methods of transmitting information about performance during the Middle Ages. How, and why, did some individuals and communities choose to record certain practices, while others did not? How do we tell a prescriptive text from a proscriptive one? If we grant – as we must – that the vast majority of medieval entertainments (didactic and recreational) were unscripted and improvisational, what methods can we develop in order to recover information about what was performed, when, by whom, and why? These are some of the vital questions to be addressed in this paper. © Carol Symes, 2007. All rights reserved. Proposal Narrative Symes 2 In this attempt to move us toward a new history of medieval theatre, I want to discuss two major ways in which our conceptualization of theatre and the historical evidence for it need to change, and then to outline just a few of the very significant gains that will be made if those changes are effected.