Complete Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Animated Avatar to Interpret Signwriting Transcription

An Animated Avatar to Interpret SignWriting Transcription Yosra Bouzid Mohamed Jemni Research Laboratory of Technologies of Information and Research Laboratory of Technologies of Information and Communication & Electrical Engineering (LaTICE) Communication & Electrical Engineering (LaTICE) ESSTT, University of Tunis ESSTT, University of Tunis [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—People with hearing disability often face multiple To address this issue, different methods and technologies barriers when attempting to interact with hearing society. geared towards deaf communication have been suggested over The lower proficiency in reading, writing and understanding the the last decades. For instance, the use of sign language spoken language may be one of the most important reasons. interpreters is one of the most common ways to ensure a Certainly, if there were a commonly accepted notation system for successful communication between deaf and hearing persons in sign languages, signed information could be provided in written direct interaction. But according to a WFD survey in 2009, 13 form, but such a system does not exist yet. SignWriting seems at countries out of 93 do not have any sign language interpreters, present the best solution to the problem of SL representation as it and in many of those countries where there are interpreters, was intended as a practical writing system for everyday there are serious problems in finding qualified candidates. communication, but requires mastery of a set of conventions The digital technologies, particularly video and avatar-based different from those of the other transcriptions systems to become a proficient reader or writer. To provide additional systems, contribute, in turn, in bridging the communication support for deaf signers to learn and use such notation, we gap. -

A Human-Editable Sign Language Representation for Software Editing—And a Writing System?

A human-editable Sign Language representation for software editing—and a writing system? Michael Filhol [email protected] LIMSI, CNRS, Université Paris Saclay Orsay, France Abstract To equip SL with software properly, we need an input system to rep- resent and manipulate signed contents in the same way that every day software allows to process written text. Refuting the claim that video is good enough a medium to serve the purpose, we propose to build a repres- entation that is: editable, queryable, synthesisable and user-friendly—we define those terms upfront. The issue being functionally and conceptually linked to that of writing, we study existing writing systems, namely those in use for vocal languages, those designed and proposed for SLs, and more spontaneous ways in which SL users put their language in writing. Ob- serving each paradigm in turn, we move on to propose a new approach to satisfy our goals of integration in software. We finally open the prospect of our proposition being used outside of this restricted scope, as a writing system in itself, and compare its properties to the other writing systems presented. 1 Motivation and goals The main motivation here is to equip Sign Language (SL) with software and foster implementation as available tools for SL are paradoxically limited in such digital times. For example, translation assisting software would help respond arXiv:1811.01786v1 [cs.CL] 5 Nov 2018 to the high demand for accessible content and information. But equivalent text-to-text software relies on source and target written forms to work, whereas similar SL support seems impossible without major revision of the typical user interface. -

Greek Alphabet ( ) Ελληνικ¿ Γρ¿Μματα

Greek alphabet and pronunciation 9/27/05 12:01 AM Writing systems: abjads | alphabets | syllabic alphabets | syllabaries | complex scripts undeciphered scripts | alternative scripts | your con-scripts | A-Z index Greek alphabet (ελληνικ¿ γρ¿μματα) Origin The Greek alphabet has been in continuous use for the past 2,750 years or so since about 750 BC. It was developed from the Canaanite/Phoenician alphabet and the order and names of the letters are derived from Phoenician. The original Canaanite meanings of the letter names was lost when the alphabet was adapted for Greek. For example, alpha comes for the Canaanite aleph (ox) and beta from beth (house). At first, there were a number of different versions of the alphabet used in various different Greek cities. These local alphabets, known as epichoric, can be divided into three groups: green, blue and red. The blue group developed into the modern Greek alphabet, while the red group developed into the Etruscan alphabet, other alphabets of ancient Italy and eventually the Latin alphabet. By the early 4th century BC, the epichoric alphabets were replaced by the eastern Ionic alphabet. The capital letters of the modern Greek alphabet are almost identical to those of the Ionic alphabet. The minuscule or lower case letters first appeared sometime after 800 AD and developed from the Byzantine minuscule script, which developed from cursive writing. Notable features Originally written horizontal lines either from right to left or alternating from right to left and left to right (boustophedon). Around 500 BC the direction of writing changed to horizontal lines running from left to right. -

Expanding Information Access Through Data-Driven Design

©Copyright 2018 Danielle Bragg Expanding Information Access through Data-Driven Design Danielle Bragg A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2018 Reading Committee: Richard Ladner, Chair Alan Borning Katharina Reinecke Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Computer Science & Engineering University of Washington Abstract Expanding Information Access through Data-Driven Design Danielle Bragg Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Richard Ladner Computer Science & Engineering Computer scientists have made progress on many problems in information access: curating large datasets, developing machine learning and computer vision, building extensive networks, and designing powerful interfaces and graphics. However, we sometimes fail to fully leverage these modern techniques, especially when building systems inclusive of people with disabilities (who total a billion worldwide [168], and nearly one in five in the U.S. [26]). For example, visual graphics and small text may exclude people with visual impairments, and text-based resources like search engines and text editors may not fully support people using unwritten sign languages. In this dissertation, I argue that if we are willing to break with traditional modes of information access, we can leverage modern computing and design techniques from computer graphics, crowdsourcing, topic modeling, and participatory design to greatly improve and enrich access. This dissertation demonstrates this potential -

Signwriting Symbols to Students

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4342 L2/12-321 2012-10-14 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal for encoding Sutton SignWriting in the UCS Source: Michael Everson, Martin Hosken, Stephen Slevinski, and Valerie Sutton Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2012-10-14 Replaces: N4015 1. Introduction. SignWriting is a script developed in 1974 by Valerie Sutton, the inventor of Sutton Movement Writing, who two years earlier had developed DanceWriting. SignWriting is a featural script, its glyphs being visually iconic as well as in their spatial arrangement in text, which represents a sort of snapshot of any given sign. SignWriting is currently being used to write the following Sign Languages: American Sign Language (in USA, English-speaking Canada) Japanese Sign Language Arabian Sign Languages Malawi Sign Language Australian Sign Language Malaysian Sign Language Bolivian Sign Language Maltese Sign Language Brazilian Sign Language Mexican Sign Language British Sign Language Nepalese Sign Language Catalan Sign Language New Zealand Sign Language Colombian Sign Language Nicaraguan Sign Language Czech Sign Language Norwegian Sign Language Danish Sign Language Peruvian Sign Language Dutch Sign Language Philippines Sign Language Ethiopian Sign Language Polish Sign Language Finnish Sign Language Portugese Sign Language Flemish Sign Language Québec Sign Language French-Belgian Sign Language South African Sign Language French Sign Language Spanish Sign Language German Sign Language Swedish Sign Language Greek Sign Language Swiss Sign Language Irish Sign Language Taiwanese Sign Language Italian Sign Language Tunisian Sign Language A variety of literature exists in SignWriting. -

Orality in Medieval Drama Speech-Like Features in the Middle English Comic Mystery Plays

Dissertation zur Erlangung des philosophischen Doktorgrades Orality in Medieval Drama Speech-Like Features in the Middle English Comic Mystery Plays vorgelegt von Christiane Einmahl an der Fakultät Sprach-, Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaften der Technischen Universität Dresden am 16. Mai 2019 Table of Contents 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Premises and aims ................................................................................................................2 1.2 Outline of the study .............................................................................................................10 2 Comedy play texts as a speech-related genre ........................................................................13 2.1 Speech-like genres and 'communicative immediacy'...........................................................13 2.2 Play texts vs. 'real' spoken discourse...................................................................................17 2.3 Conclusions.........................................................................................................................25 3 'Comedy' in the mystery cycles................................................................................................26 3.1 The medieval sense of 'comedy'..........................................................................................26 3.2 Medieval attitudes to laughter..............................................................................................37 -

A Cross-Linguistic Guide to Signwriting ® a Phonetic Approach

A Cross-Linguistic ® Guide to SignWriting A phonetic approach Stephen Parkhurst Dianne Parkhurst A Cross-Linguistic Guide to SignWriting ®: A phonetic approach ©2008 Stephen Parkhurst Revision 2010 For use at SIL-UND courses during the summer of 2010. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recorded or otherwise, without permission from the authors. Stephen and Dianne Parkhurst E-mail: [email protected] A note from the authors SignWriting®, also known as Sutton Movement Writing for Sign Language, was invented by Valerie Sutton in 1974. Over the years the system has changed significantly and has gradually grown in acceptance and popularity in more than 30 countries. While there are other writing systems and notation systems for writing signed languages, we have not found any system that is as useful for writing accurately any sign or movement (including all non-manual movements and expressions) with relative ease and speed. It is also the only writing system that we have tried that is possible to read faster than one can physically produce the signs (outpacing even photos and line drawings in ease and speed of reading). We have taken much of the material for this manual from a course we developed for teaching SignWriting (SW) to Deaf adults in Spain. That course in Spain focused on teaching the symbols of SW that are used in Spanish Sign Language (or LSE, for Lengua de Signos Española) with a heavy focus on reading. -

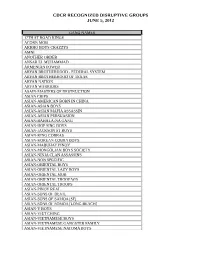

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

Analysis of Notation Systems for Machine Translation of Sign Languages

Analysis of Notation Systems for Machine Translation of Sign Languages Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Science (Honours) of Rhodes University Jessica Jeanne Hutchinson Grahamstown, South Africa November 2012 Abstract Machine translation of sign languages is complicated by the fact that there are few stan- dards for sign languages, both in terms of the actual languages used by signers within regions and dialogue groups, and also in terms of the notations with which sign languages are represented in written form. A standard textual representation of sign languages would aid in optimising the translation process. This area of research still needs to determine the best, most efficient and scalable tech- niques for translation of sign languages. Being a young field of research, there is still great scope for introducing new techniques, or greatly improving on previous techniques, which makes comparing and evaluating the techniques difficult to do. The methods used are factors which contribute to the process of translation and need to be considered in an evaluation of optimising translation systems. This project analyses sign language notation systems; what systems exists, what data is currently available, and which of them might be best suited for machine translation purposes. The question being asked is how using a textual representation of signs could aid machine translation, and which notation would best suit the task. A small corpus of SignWriting data was built and this notation was shown to be the most accessible. The data was cleaned and run through a statistical machine translation system. The results had limitations, but overall are comparable to other translation systems, showing that translation using a notation is possible, but can be greatly improved upon. -

One Path Or Two? Using Grammatical Class

171 Chapter 7 Although human language is thought to be at least 200 000 years old (Mithen, 2005), precisely when and how it emerged remain largely a mystery. Unlike other human achievements such as the use of tools, there is no archaeological trail to follow; instead, the evolution of language can only be inferred (Olsen, 1998). As a result, contemporary theories of language evolution range from proto-speech (Steklis & Raleigh, 1979) through to proto-sign models (Zlatev, 2008). Although it remains a process of educated guesswork, it has traditionally been informed through studies of modern infant language acquisition (Young, Merin, Rogers & Ozonoff, 2009) or animal communication systems (Bonatti, Peña, Nespor & Mehler, 2005). More recently, the development of neuroimaging technologies such as MEG and fMRI has allowed a vastly improved understanding of how the modern human brain functions, while concurrent advances in computing and analysis techniques have allowed older technologies such as EEG to enjoy a research renaissance (e.g. Klimesch, 2011, 2012; Nyström, Ljunghammar, Rosander & von Hofsten, 2011; Sauseng, Klimesch, Schabus & Doppelmayr, 2005). Despite these advancements, there is still a lack of agreement on both when and how human language evolved. To this end, the purpose of the current thesis was to examine grammatical class processing (nouns versus verbs) in mature language speakers. By comparing the one and two path models of such processing, it was proposed that results could be interpreted within an evolutionary context, providing support (albeit inferential) for either the protosign/protospeech or the mixed model (coevolution) of language. This specific feature or function of language processing was chosen for a number of reasons: (1) It is unlikely that language emerged as a complete system; that is, it is improbable that the first thing ever uttered by an early human was along the lines of “Hey guess what? I can talk!!”. -

Glendale Police Department

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ClPY O!.F qL'J;9{'jJ.!JL[/E • Police 'Department 'Davit! J. tJ1iompson CfUt! of Police J.1s preparea 6y tfit. (jang Investigation Unit -. '. • 148396 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been g~Qted bY l' . Giend a e C1ty Po11ce Department • to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyright owner. • TABLEOFCON1ENTS • DEFINITION OF A GANG 1 OVERVIEW 1 JUVENILE PROBLEMS/GANGS 3 Summary 3 Ages 6 Location of Gangs 7 Weapons Used 7 What Ethnic Groups 7 Asian Gangs 8 Chinese Gangs 8 Filipino Gangs 10 Korean Gangs 1 1 Indochinese Gangs 12 Black Gangs 12 Hispanic Gangs 13 Prison Gang Influence 14 What do Gangs do 1 8 Graffiti 19 • Tattoo',;; 19 Monikers 20 Weapons 21 Officer's Safety 21 Vehicles 21 Attitudes 21 Gang Slang 22 Hand Signals 22 PROFILE 22 Appearance 22 Headgear 22 Watchcap 22 Sweatband 23 Hat 23 Shirts 23 PencHetons 23 Undershirt 23 T-Shirt 23 • Pants 23 ------- ------------------------ Khaki pants 23 Blue Jeans 23 .• ' Shoes 23 COMMON FILIPINO GANG DRESS 24 COMMON ARMENIAN GANG DRESS 25 COrvtMON BLACK GANG DRESS 26 COMMON mSPANIC GANG DRESS 27 ASIAN GANGS 28 Expansion of the Asian Community 28 Characteristics of Asian Gangs 28 Methods of Operations 29 Recruitment 30 Gang vs Gang 3 1 OVERVIEW OF ASIAN COMMUNITIES 3 1 Narrative of Asian Communities 3 1 Potential for Violence 32 • VIETNAMESE COMMUNITY 33 Background 33 Population 33 Jobs 34 Politics 34 Crimes 34 Hangouts 35 Mobility 35 Gang Identification 35 VIETNAMESE YOUTH GANGS 39 Tattoo 40 Vietnamese Background 40 Crimes 40 M.O. -

Ashesi University College Enabling Sign Language Instruction With

Ashesi University College Enabling Sign Language Instruction with Technology: the Case of Developing a Computerized Learning Tool for Ghanaian Sign Language (GhSL) Diana Dayaka Osei 2012 ASHESI UNIVERSITY COLLEGE ENABLING SIGN LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION WITH TECHNOLOGY: THE CASE OF DEVELOPING A COMPUTERIZED LEARNING TOOL FOR GHANAIAN SIGN LANGUAGE (GhSL) By DIANA DAYAKA OSEI Thesis submitted to the Department of Computer Science, Ashesi University College In partial fulfillment of Bachelor of Science degree in Computer Science APRIL 2012 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of my own original work and that no part of it has been presented for another degree in this university or elsewhere. Candidate’s Signature: ……………………………………………………………………… Candidate’s Name: ……………………………………………………………………………… Date: …………………………………………………………………………………………………… I hereby declare that the preparation and presentation of the dissertation were supervised in accordance with the guidelines on supervision of thesis laid down by Ashesi University College. Supervisor’s Signature: …………………………………………………………………… Supervisor’s Name: …………………………………………………………………………… Date: …………………………………………………………………………………………………… i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank Educational Pathways International (EPI) for the educational scholarship to study at Ashesi University College. Here, I was able to discover myself, to learn more about the world of technology (with the advantage of a liberal arts core) and to assess how best I can make a contribution to the development of my country using technology. I am grateful to computer science faculty at Ashesi for pushing us (i.e. 2012CS/MIS class) to give our best. I thank Dr. G. Ayorkor Korsah, for giving me the DeSIGN research paper which actually served as my first full text resource and launched me on the path to other research papers’ findings and personal communications that helped me complete this project.