Inducing Flow in Board Games Through Augmented Audio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magicrealm.Net Forum Archive

WWW.MAGICREALM.NET FORUMS ARCHIVE This archive contains a complete record of all messages posted on the forums at MagicRealm.net The last message posted here is dated 14 Feb 2004. The archive is organized in the same manner as the forums were: two main sections, and seven subsections. Each discussion topic is linked to a bookmark. The discussion topics are sorted from oldest to newest within each subsection. This is the opposite of how they were sorted in the original forums, but it was easier to build and maintain the archive in this way. Known problems: The polls in the “Software” subsection could not be archived. Many of the URL’s came through as blank lines. The forum software had a flaw: at the start of each discussion topic, it lists the topic name followed by “started by [name]” – but instead of using the name of the person who started the topic, it used the name of the last person to post to that topic. MRNet Forums [Powered by Ikonboard] http://www.magicrealm.net/cgi-bin/ikonboard/ikonboard.cgi... Printable Version of Topic -MRNet Forums +--Forum: Expansions and Variants +---Topic: New Characters started by fiscused Posted by: fiscused on Sep. 04 2001,07:28 Thought I'd throw up the beginning of a new character idea here. Monk: A quiet, dedicated man, the monk is master of dealing damage, either with his bare hands or with weapons. advantages: Poverty: The monk begins with zero gold and may never gain gold in any way. He can barter with others using the gold value of items, but he may never acquire gold. -

Spring 2008 Issue

www.diplomacyworld.net Variety Melange Variants: The Spice of Life Notes From the Editor Welcome back to another issue of Diplomacy World. that continues in the coming issues as well! This is now my fifth issue since returning as Lead Editor, and in some ways it was the hardest issue to do. I This issue you’ll also find the results of the latest believe this was simply a case of all the additional time Diplomacy World Writing Contest. While I would have and effort that went into doing Issue #100. It wasn’t until liked to get more entries than I did, at least we received #100 was finished and uploaded to the web site that I enough to actually award the prizes this time! realized how many extra hours I’d been spending each Congratulations to our winners, and keep your eyes week trying to assemble all that material. Sitting back open for future writing contests, or contests of other the next day, I was a bit worried about whether I had run types. If you have suggestions, please let me know. the well (or my personal gas tank) dry. Which leads me into the usual quarterly mantra: this Fortunately, that wasn’t the case. First of all, we had a particular issue, and Diplomacy World as a whole, is few wonderful pieces of material set aside for this issue, only as good as the articles you hobby members submit. starting with Stephen Agar’s variant symphony and I can’t write the whole thing myself, not even with the David McCrumb’s designer notes on 1499: The Italian assistance of the DW Staff…we need your ideas, your Wars. -

GAME AUCTION! Here Be Books & Games

Game Auction FAQ 5 Activities to Distract Kids Take 5 & Take a Number - Everything you need to know on a Rainy Day Great Games from Germany FREE Open Gaming & Learn to Play Sci Fi & Fantasy Book Club Meeting Board Game Auction FAQ What can I buy with Store Credit? to accommodate you, but we do not guarantee we’ll be Who would become King of the Hill? Save Hogwarts Here;s a run-down of how each game plays, as well as Take 5 plays fast and is deceptively simple. While it may your # Card to form your Bull Pile. e lower • You may not place a card between two cards in a about buying or selling games at April showers bring May flowers Two classic games from Germany, some variant rules that can add more replayability and ...with Excel & We’re hosting our fth Game Auction You can use Store Credit to purchase in-stock merchan- able to do so. It would be better to make arrangements Or in this case, King of Tokyo? It’s a roll e evil forces of He Who initially seem very luck-based, on repeated plays you’ll numbered card you just played becomes the start row. You may only place cards at the beginning or the Game Auction. and bored and fidgety kids. Luck- now available together in the U.S. Events Saturdays in April! Friday, April 12, 6pm to 8pm strategy to your Take 5 games. WordPress Saturday, April 27 from 6pm to 11pm at dise, as well as, special orders and preorders. -

Digitising Boardgames: Issues and Tensions

Digitising Boardgames: Issues and Tensions Melissa J. Rogerson, Martin Gibbs, Wally Smith Microsoft Research Centre for Social Natural User Interfaces The University of Melbourne Parkville, Vic, 3010 +61 3 8344 1394, +61 3 8344 1494 [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT In this paper, we discuss the different ways in which modern European boardgames (“Eurogames”) are converted for digital play. We review digitised versions of three popular tabletop boardgames: Puerto Rico, Agricola and Ascension. Using these examples, we demonstrate the tension between the interaction metaphor of the original analogue medium and the metaphor of a digital game. We describe the importance of housekeeping chores to gameplay and position them as a form of articulation work, which is typically hidden by digital implementations. Further, we demonstrate the types of information that are created through digital play and discuss how this influences game play of both digital and physical boardgames. Keywords Board games, interaction metaphor, articulation, theorycrafting, informating INTRODUCTION Boardgames, traditionally played in their physical format using boards, cards, dice, playing tokens and the like, are increasingly being translated to digital form for devices such as smartphones, computers, videogame systems and tablets. To date, little attention has been paid to how and the degree to which this digitisation affects or transforms the experience of play. There is growing tension between the desire for digitised boardgames to be true to the interaction metaphor (Sharp et al. 2007, 58-63) of the original medium and the desire to extend the game to explore the potential of the digital medium. -

Dragon Magazine

May 1980 The Dragon feature a module, a special inclusion, or some other out-of-the- ordinary ingredient. It’s still a bargain when you stop to think that a regular commercial module, purchased separately, would cost even more than that—and for your three bucks, you’re getting a whole lot of magazine besides. It should be pointed out that subscribers can still get a year’s worth of TD for only $2 per issue. Hint, hint . And now, on to the good news. This month’s kaleidoscopic cover comes to us from the talented Darlene Pekul, and serves as your p, up and away in May! That’s the catch-phrase for first look at Jasmine, Darlene’s fantasy adventure strip, which issue #37 of The Dragon. In addition to going up in makes its debut in this issue. The story she’s unfolding promises to quality and content with still more new features this be a good one; stay tuned. month, TD has gone up in another way: the price. As observant subscribers, or those of you who bought Holding down the middle of the magazine is The Pit of The this issue in a store, will have already noticed, we’re now asking $3 Oracle, an AD&D game module created by Stephen Sullivan. It for TD. From now on, the magazine will cost that much whenever we was the second-place winner in the first International Dungeon Design Competition, and after looking it over and playing through it, we think you’ll understand why it placed so high. -

Ah-80Catalog-Alt

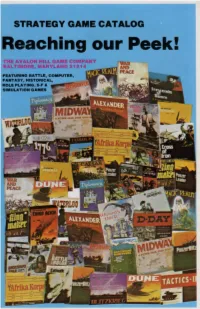

STRATEGY GAME CATALOG I Reaching our Peek! FEATURING BATTLE, COMPUTER, FANTASY, HISTORICAL, ROLE PLAYING, S·F & ......\Ci l\\a'C:O: SIMULATION GAMES REACHING OUR PEEK Complexity ratings of one to three are introduc tory level games Ratings of four to six are in Wargaming can be a dece1v1ng term Wargamers termediate levels, and ratings of seven to ten are the are not warmongers People play wargames for one advanced levels Many games actually have more of three reasons . One , they are interested 1n history, than one level in the game Itself. having a basic game partlcularly m1l11ary history Two. they enroy the and one or more advanced games as well. In other challenge and compet111on strategy games afford words. the advance up the complexity scale can be Three. and most important. playing games is FUN accomplished within the game and wargaming is their hobby The listed playing times can be dece1v1ng though Indeed. wargaming 1s an expanding hobby they too are presented as a guide for the buyer Most Though 11 has been around for over twenty years. 11 games have more than one game w1th1n them In the has only recently begun to boom . It's no [onger called hobby, these games w1th1n the game are called JUSt wargam1ng It has other names like strategy gam scenarios. part of the total campaign or battle the ing, adventure gaming, and simulation gaming It game 1s about Scenarios give the game and the isn 't another hoola hoop though. By any name, players variety Some games are completely open wargam1ng 1s here to stay ended These are actually a game system. -

TODD LOCKWOOD the Neverwinter™ Saga, Book IV the LAST THRESHOLD ©2013 Wizards of the Coast LLC

ThE ™ SAgA IVBooK COVER ART TODD LOCKWOOD The Neverwinter™ Saga, Book IV THE LAST THRESHOLD ©2013 Wizards of the Coast LLC. This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unau- thorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast LLC. Published by Wizards of the Coast LLC. Manufactured by: Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 2 Roundwood Ave, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1AZ, UK. DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, WIZARDS OF THE COAST, NEVERWINTER, FORGOTTEN REALMS, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast LLC in the USA and other countries. All characters in this book are fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coin- cidental. All Wizards of the Coast characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast LLC. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. Cover art by Todd Lockwood First Printing: March 2013 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN: 978-0-7869-6364-5 620A2245000001 EN Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the Library of Congress For customer service, contact: U.S., Canada, Asia Pacific, & Latin America: Wizards of the Coast LLC, P.O. Box 707, Renton, WA 98057- 0707, +1-800-324-6496, www.wizards.com/customerservice U.K., Eire, & South Africa: Wizards of the Coast LLC, c/o Hasbro UK Ltd., P.O. Box 43, Newport, NP19 4YD, UK, Tel: +08457 12 55 99, Email: [email protected] All other countries: Wizards of the Coast p/a Hasbro Belgium NV/SA, Industrialaan 1, 1702 Groot- Bijgaarden, Belgium, Tel: +32.70.233.277, Email: [email protected] Visit our web site at www.dungeonsanddragons.com Prologue The Year of the Reborn Hero (1463 DR) ou cannot presume that this creature is natural, in any sense of Ythe word,” the dark-skinned Shadovar woman known as the Shifter told the old graybeard. -

Win.Spielen.At WIN - Spiele Magazin - Den Neuen Spielen Verpflichtet! Spiel `01 in Essen Wartet!

23. September 2001 * Nr. 297 ISSN 0257-361X aWIN 25. Jahrgang win.spielen.at WIN - Spiele Magazin - Den neuen Spielen verpflichtet! Spiel `01 in Essen wartet! SPIELEN IN ÖSTERREICH Deutscher Spiele Preis Vorschau auf Spiel `01 Auch die 4. Internationale Siedler von Bitte besuchen Sie 2001: Mit 1544 Einsendungen per Unsere Vorschau auf die Spiel‘ 01, die unser Portal Karten, Internet und Stimmbögen von Internationalen Spieltage mit Comic Catan-Meisterschaft wird in Essen aus- Spielern, Spielekreisen, Journalisten Action vom 18. bis 21. Oktober 2001 getragen, die Endrunde der 32 besten www.spielen.at und Händlern wurde der Deutsche Spieler wird Samstag am 20. Oktober Spiele Preis 2001 vom Friedhelm Die SPIEL mit ihrem wohl einmaligen ab 10.30 Uhr auf der Messebrücke Merz Verlag vergeben. Charakter findet heuer zum neunzehn- gespielt. ten Mal statt und wird wieder der 1. CARCASSONNE vom Hans im Höhepunkt im Spielejahr für ale sein, Wer sich kostenlos den GenCon in Mil- Glück Verlag ist Gewinner des Haupt- die am Spiel interessiert sind. waukee anschauen möchte, sollte an preises und Träger des Deutschen der SHADOWFIST European Champi- Spiele Preises 2001. Über 550 Aussteller aus 17 Nationen onship am Stand der Firma Z-Man Auf den weiteren Plätzen der Top-Ten- zeigen Games in Halle 6 teilnehmen, der Liste des Deutschen Spiele Preises Gesellschafts-, Familien-, Erwachse- Gewinner bekommt ein Flugticket zum 2001 folgen die Titel: nen- und Kinderspiele GenCon, freie Unterkunft in Milwaukee 2. MEDINA von Stefan Dorra (Hans im Strategie-, Post-, Abenteuer-, Fantasy- und freien Eintritt zum GenCon. Glück Verlag) und Science-Fictionspiele 3. DIE HÄNDLER VON GENUA von Bridge, Go, Shogi Auch Spieleautoren sind auf der Spiel Rüdiger Dorn (Alea/Ravensburger) Sammelkarten fast an allen Ständen zu finden, man 4. -

Designing Analog Learning Games: Genre Affordances, Limitations and Multi-Game Approaches

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Articles Faculty & Staff Scholarship Summer 9-2020 Designing Analog Learning Games: Genre Affordances, Limitations and Multi-Game Approaches Owen Gottlieb Rochester Institute of Technology Ian Schreiber Rochester Institute of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/article Part of the African History Commons, Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Civil Law Commons, Cultural History Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Educational Technology Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, Game Design Commons, History of Religion Commons, Instructional Media Design Commons, Interactive Arts Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legal Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Studies Commons, Medieval History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, Religion Law Commons, Religious Education Commons, Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Commons, Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Gottlieb, Owen and Schreiber, Ian. (2020). Designing Analog Learning Games: Genre Affordances, Limitations, and Multi-Game Approaches. In Douglas Brown and Esther MacCallum Stewart (editors), Rerolling Boardgames: Essays on Themes, Systems, Experiences, and Ideologies (pp. 195-211). McFarland & Company, Inc. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty & Staff Scholarship at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Appears in: Gottlieb, Owen and Schreiber, Ian. (2020). Designing Analog Learning Games: Genre Affordances, Limitations, and Multi-Game Approaches. -

Major Developments in the Evolution of Tabletop Game Design

Major Developments in the Evolution of Tabletop Game Design Frederick Reiber Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences University of California Irvine Irvine, USA [email protected] Abstract—Tabletop game design is very much an incremental these same concepts can and have been used in video game art. Designers build upon the ideas of previous games, often design. improving and combining already defined game mechanics. In Although some of these breakthroughs might be already this work, we look at a collection of the most impactful tabletop game designs, or games that have caused a significant shift in known by long time game designers, it is important to formally the tabletop game design space. This work seeks to record those document these developments. By doing so, we can not only shifts, and does so with the aid of empirical analysis. For each bridge the gap between experienced and novice game design- game, a brief description of the game’s history and mechanics ers, but we can also begin to facilitate scholarly discussion on is given, followed by a discussion on its impact within tabletop the evolution of games. Furthermore, this research is of interest game design. to those within the tabletop game industry as it provides Index Terms—Game Design, Mechanics, Impact. analysis on major developments in the field. It is also our belief that this work can be useful to academics, specifically I. INTRODUCTION those in the fields of game design, game analytics, and game There are many elements that go into creating a successful generation AI. tabletop game. -

Monte Carlo Methods for the Game Kingdomino

Monte Carlo Methods for the Game Kingdomino Magnus Gedda, Mikael Z. Lagerkvist, and Martin Butler Tomologic AB Stockholm, Sweden Email: fi[email protected] Abstract—Kingdomino is introduced as an interesting game for enhancements have been presented for MCTS, both general studying game playing: the game is multiplayer (4 independent and domain-dependent, increasing its performance even further players per game); it has a limited game depth (13 moves per for various games [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. For shallow game player); and it has limited but not insignificant interaction among players. trees it is still unclear which Monte Carlo method performs Several strategies based on locally greedy players, Monte Carlo best since available recommendations only concern games Evaluation (MCE), and Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) are with deep trees. presented with variants. We examine a variation of UCT called Kingdomino [19] is a new board game which won the progressive win bias and a playout policy (Player-greedy) focused prestigious Spiel des Jahres award 2017. Like many other on selecting good moves for the player. A thorough evaluation is done showing how the strategies perform and how to choose eurogames it has a high branching factor but differs from parameters given specific time constraints. The evaluation shows the general eurogame with its shallow game tree (only 13 that surprisingly MCE is stronger than MCTS for a game like rounds). It has frequent elements of nondeterminism and Kingdomino. differs from zero sum games in that the choices a player makes All experiments use a cloud-native design, with a game server generally have limited effect on its opponents. -

Lost Cities Rulebook

Explanation of the White Column: Hint: As you can see in the example, it is better Scoring The wager card doubles the value of not to start an expedition in the first place if Example: the column. Since no other cards you can’t bring it to a satisfactory conclusion. The player has have been placed, only the Also, you should only play wager cards if you expedition costs are incurred, which have enough cards for a column and there is formed the are doubled. still time to place those cards. following columns: 7 7 6. 6. The Game Designer Reiner Knizia, born in 1957, lives in Windsor, Great Britain. He holds a Ph.D. in Mathematics and has published numerous games in Germany and abroad. Among his greatest achievements are the German awards “Deutscher Spiele Preis” (obtained in 1993 and 1998) and “Spiel des Jahres 2008” (the latter for “Keltis,” a game based on “Lost Cities”). Reiner Knizia specializes in games whose simple rules give players much freedom of choice. Kosmos has published many of his games. The game designer and publisher thank the many game testers and people who reviewed the game rules. The game designer particularly thanks Dave Farquhar, Ross Inglis, Kevin Jacklin, Lieselotte Knizia, Elke Knop, and Chris Lawson. The player has earned 18 points. 3 + 0 - 40 - 10 + 45 + 20 (bonus) = 18 Editorial Team: TM-Spiele Art: Grafik Studio Krüger: Claus Stephan Graphic Design: Pohl & Rick Grafikdesign, Michaela Kienle/Fine Tuning English Translation: Gavin Allister 23 0 0 15 35 Sum English Text Editing: Ted McGuire Additional Design: Dan Freitas Expedition -20 No cost -20 -20 -20 Costs © 1999, 2012 Franckh-Kosmos Verlags-GmbH & Co.