Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issues in Indian Politics –

ISSUES IN INDIAN POLITICS – Core Course of BA Political Science - IV semester – 2013 Admn onwards 1. 1.The term ‘coalition’ is derived from the Latin word coalition which means a. To merge b. to support c. to grow together d. to complement 2. Coalition governments continue to be a. stable b. undemocratic c. unstable d. None of these 3. In coalition government the bureaucracy becomes a. efficient b. all powerful c. fair and just d. None of these 4. who initiated the systematic study of pressure groups a. Powell b. Lenin c. Grazia d. Bentley 5. The emergence of political parties has accompanied with a. Grow of parliament as an institution b. Diversification of political systems c. Growth of modern electorate d. All of the above 6. Party is under stood as a ‘doctrine by a. Guid-socialism b. Anarchism c. Marxism d. Liberalism 7. Political parties are responsible for maintaining a continuous connection between a. People and the government b. President and the Prime Minister c. people and the opposition d. Both (a) and (c) 1 8. The first All India Women’s Organization was formed in a. 1918 b. 1917 c.1916 d. 1919 9. ------- belong to a distinct category of social movements with the ideology of class conflict as their basis. a. Peasant Movements b. Womens movements c. Tribal Movements d. None of the above 10.Rajni Kothari prefers to call the Indian party system as a. Congress system b. one party dominance system c. Multi-party systems d. Both a and b 11. What does DMK stand for a. -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination by Purvi Mehta A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Chair Professor Pamela Ballinger Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Matthew Hull Professor Mrinalini Sinha Dedication For my sister, Prapti Mehta ii Acknowledgements I thank the dalit activists that generously shared their work with me. These activists – including those at the National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights, Navsarjan Trust, and the National Federation of Dalit Women – gave time and energy to support me and my research in India. Thank you. The research for this dissertation was conducting with funding from Rackham Graduate School, the Eisenberg Center for Historical Studies, the Institute for Research on Women and Gender, the Center for Comparative and International Studies, and the Nonprofit and Public Management Center. I thank these institutions for their support. I thank my dissertation committee at the University of Michigan for their years of guidance. My adviser, Farina Mir, supported every step of the process leading up to and including this dissertation. I thank her for her years of dedication and mentorship. Pamela Ballinger, David Cohen, Fernando Coronil, Matthew Hull, and Mrinalini Sinha posed challenging questions, offered analytical and conceptual clarity, and encouraged me to find my voice. I thank them for their intellectual generosity and commitment to me and my project. Diana Denney, Kathleen King, and Lorna Altstetter helped me navigate through graduate training. -

U.O.No. 11099/2019/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 21.08.2019 Biju George K Assistant Registrar Forwarded / by Order Section

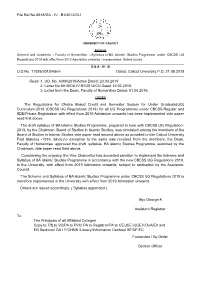

File Ref.No.8818/GA - IV - B1/2012/CU UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT Abstract General and Academic - Faculty o f Humanities - Syllabus o f BA Islamic Studies Programme under CBCSS UG Regulations 2019 with effect from 2019 Admission onwards - Implemented- Orders issued G & A - IV - B U.O.No. 11099/2019/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 21.08.2019 Read:-1. UO. No. 4368/2019/Admn Dated: 23.03.2019 2. Letter No.8818/GA IV B1/2012/CU Dated:15.06.2019. 3. Letter from the Dean, Faculty of Humanities Dated: 01.08.2019. ORDER The Regulations for Choice Based Credit and Semester System for Under Graduate(UG) Curriculum-2019 (CBCSS UG Regulations 2019) for all UG Programmes under CBCSS-Regular and SDE/Private Registration with effect from 2019 Admission onwards has been implemented vide paper read first above. The draft syllabus of BA Islamic Studies Programme, prepared in tune with CBCSS UG Regulation- 2019, by the Chairman, Board of Studies in Islamic Studies, was circulated among the members of the Board of Studies in Islamic Studies vide paper read second above as provided under Calicut University First Statutes -1976. Since,no exception to the same was received from the members, the Dean, Faculty of Humanities approved the draft syllabus BA Islamic Studies Programme, submited by the Chairman, vide paper read third above. Considering the urgency, the Vice Chancellor has accorded sanction to implement the Scheme and Syllabus of BA Islamic Studies Programme in accordance with the new CBCSS UG Regulations 2019, in the University, with effect from 2019 Admission onwards, subject to ratification by the Academic Council. -

Members of the Local Authorities Alappuzha District

Price. Rs. 150/- per copy UNIVERSITY OF KERALA Election to the Senate by the member of the Local Authorities- (Under Section 17-Elected Members (7) of the Kerala University Act 1974) Electoral Roll of the Members of the Local Authorities-Alappuzha District Name of Roll Local No. Authority Name of member Address 1 LEKHA.P-MEMBER SREERAGAM, KARUVATTA NORTH PALAPPRAMBILKIZHAKKETHIL,KARUVATTA 2 SUMA -ST. NORTH 3 MADHURI-MEMBER POONTHOTTATHIL,KARUVATTA NORTH 4 SURESH KALARIKKAL KALARIKKALKIZHAKKECHIRA, KARUVATTA 5 CHANDRAVATHY.J, VISHNUVIHAR, KARUVATTA 6 RADHAMMA . KALAPURAKKAL HOUSE,KARUVATTA 7 NANDAKUMAR.S KIZHAKKEKOYIPURATHU, KARUVATTA 8 SULOCHANA PUTHENKANDATHIL,KARUVATTA 9 MOHANAN PILLAI THUNDILVEEDU, KARUVATTA 10 Karuvatta C.SUJATHA MANNANTHERAYIL VEEDU,KARUVATTA 11 K.R.RAJAN PUTHENPARAMBIL,KARUVATTA Grama Panchayath Grama 12 AKHIL.B CHOORAKKATTU HOUSE,KARUVATTA 13 T.Ponnamma- ThaichiraBanglow,Karuvatta P.O, Alappuzha 14 SHEELARAJAN R.S BHAVANAM,KARUVATTA NORTH MOHANKUMAR(AYYAPP 15 AN) MONEESHBHAVANAM,KARUVATTA 16 Sosamma Louis Chullikkal, Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 17 Jayamohan Shyama Nivas, Pollethai.P.O 18 Kala Thamarappallyveli,Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 19 Dinakaran Udamssery,Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 20 Rema Devi Puthenmadam, Kalvoor. P.O, Alappuzha 21 Indira Thilakan Pandyalakkal, Kalavoor. P.O, Alappuzha 22 V. Sethunath Kunnathu, Kalavoor. P.O, Alappuzha 23 Reshmi Raju Rajammalayam, Pathirappally, Alappuzha 24 Muthulekshmi Castle, Pathirappaly.P.O, Alappuzha 25 Thresyamma( Marykutty) Chavadiyil, Pathirappally, Alappuzha 26 Philomina (Suja) Vadakkan parambil, Pathirappally, Alappuzha Grama Panchayath Grama 27 South Mararikulam Omana Moonnukandathil, Pathirappally. P.O, Alappuzha 28 Alice Sandhyav Vavakkad, Pathirappally. P.O, Alappuzha 29 Laiju. M Madathe veliyil , Pathirappally P O 30 Sisily (Kunjumol Shaji) Puthenpurakkal, Pathirappally. P.O, Alappuzha 31 K.A. -

1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Near CSI Church, Kodukulanji Rural 5

No. LUNCH Home Sl. No Of LUNCH Parcel By Unit LUNCH Sponsored by of District Name of the LSGD (CDS) Kitchen Name Kitchen Place Rural / Urban Initiative Delivery No. Members (November 16 th) LSGI's (November 16 th) units (November 16 th) Near CSI church, 1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 30 0 0 Kodukulanji Ruchikoottu Janakiya Coir Machine Manufacturing 2 Alappuzha Alappuzha North Urban 4 Janakeeya Hotel 194 0 20 Bhakshanasala Company Samrudhi janakeeya 3 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Pazhaveedu Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 70 0 0 bhakshanashala Community kitchen 4 Alappuzha Alappuzha South MCH junction Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 155 197 thavakkal group 5 Alappuzha Ambalppuzha North Swaruma Neerkkunnam Rural 10 Janakeeya Hotel 0 0 0 6 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha South Patheyam Amayida Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 100 10 7 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Hanna catering unit JMS hall,arattupuzha Rural 6 Janakeeya Hotel 202 0 0 8 Alappuzha Arookutty Ruchi Kombanamuri Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 55 27 0 9 Alappuzha Aroor Navaruchi Vyasa charitable trust Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 20 0 0 10 Alappuzha Aryad Anagha Catering Near Aryad Panchayat Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 7 45 0 Sasneham Janakeeya 11 Alappuzha Bharanikavu Koyickal chantha Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 172 0 0 Hotel 12 Alappuzha Budhanoor sampoorna mooshari parampil building Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 55 0 0 13 Alappuzha Chambakulam Jyothis Near party office Rural 4 Janakeeya Hotel 81 0 0 chengannur market building 14 Alappuzha Chenganoor SRAMADANAM Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 95 0 0 complex Chennam pallipuram 15 -

Ranklistnew-Staff-Nurse-Alp.Pdf

t ONLINE APPLICATION INVITED FOR STAFF NURSE (COVID .19 PREVENTION ACTITTVITIES) - RANK LrST NAME Address Rank Number Kufikad,Ponnad Aswathy R 1 Po,MannancheryAlappuzha 688538 Velichappatu Thayil,,{sramam Athira Mohan 2 Ward.Avalikunnu Po,Alappuzha Binu Bhavanam,Thannikunnu Lince George 3 P.0,Vettiyar,690534 Radha Radhika L Sadhanam,Mulavanathara,Pazhavana 4 P.0,Alaopuzha Athira babu Veliyil, Iklavoor P 0, Alpy 5 Manezhathu House Poonthoppu Ward Remya Mol K P 6 Avalookunnu PoAlappuzha Thekkepalackal HousglGnjiramchira Margarat T V 7 P.O,Mangalam Ward,Alpy,688007 Kelaparambil,Neendoor,Pallipad P 0, Daisy varghese B Alapy Ifochuvila House Kunnankeri P.O Renju R Alappuzha I Chittakkat, Kalath Ward, Avalookunnu linsha Rose Francis 10 P O, Alpy Chameth Padittathil,Panoor Pallana Rahila P.0,Thrikkunnappuzha 11 Adithyan M Kalliparambu,Pazhaveedu P O Alapy 72 Vadakkethaiyil South Aryad , West Of Anjusha M 13 Lhs Avalookunnu P.0 Alappuzha Reianimol T S Thottuchira Muhamma Po Alappuzha t4 Poonayar House,Chambakulam lomol fose 15 Po,Amicheri,Alappuzha Chirayil House,Valiyamaram Ward Saritha Chandran Po"Alappuzha 76 R[q.,e\- Modiyil House Karthika Chandran 77 ,Kurathikad,Mavelikara,6g0 107 Ethrkandathilhouse, North,Aryadu p Sushamol S O Alapy 18 Parambu Nilam Housg Aiirha Kumari T v Kadaharam,Thakazhy Alpy L9 Resmi Prasad Aikkarachem Cmc23 Cherthala 20 Di.ia S Dinesh Kunnumpurath,Muhamma p O,Alpy 2t Madavana House Pattanakad p faisy mol V O Cherthala 22 TC Suni Lawrence 5/1 94T,Chenguvilayakathveedu,Amba 23 u Saranya Satheesh Navaneeth,Pazhaveedu"Alpy 24 Aa Manzil,Kottamkulagara Shabana Shajahan Ward,Avalikunnu Po,,{ryad 25 Anjitha Raiu 'rlidhyalayam,Charamangalam,Muham maPO 26 Pilechi Nikarth, Pattanakkad p Devaprasad B o Cherthala 27 Sreebhayanam, Chithra Viswanathan Chunakkara Eas! 28 Sarath covind B po, Thoppuveli ,S L Puram 29 Palliveedu, puram. -

Alappuzha District

Sheet1 Price. Rs. 150/- per copy UNIVESITY OF KERALA Election to the Senate by the member of the Local Authorities- (Under Section 17-Elected Members (7) of the Kerala University Act 1974) Electoral Roll of the Members of the Local Authorities-Alappuzha District Name of Local Sl.No Authority Name of member Address 1 LEKHA.P-MEMBER SREERAGAM, KARUVATTA NORTH 2 SUMA -ST. PALAPPRAMBILKIZHAKKETHIL,KARUVATTA NORTH 3 MADHURI-MEMBER POONTHOTTATHIL,KARUVATTA NORTH 4 SURESH KALARIKKAL KALARIKKALKIZHAKKECHIRA, KARUVATTA 5 CHANDRAVATHY.J, VISHNUVIHAR, KARUVATTA 6 RADHAMMA . KALAPURAKKAL HOUSE,KARUVATTA A 7 T NANDAKUMAR.S KIZHAKKEKOYIPURATHU, KARUVATTA T A V 8 U SULOCHANA PUTHENKANDATHIL,KARUVATTA R A K 9 MOHANAN PILLAI THUNDILVEEDU, KARUVATTA 10 C.SUJATHA MANNANTHERAYIL VEEDU,KARUVATTA 11 K.R.RAJAN PUTHENPARAMBIL,KARUVATTA 12 AKHIL.B CHOORAKKATTU HOUSE,KARUVATTA 13 T.Ponnamma- ThaichiraBanglow,Karuvatta P.O, Alappuzha 14 SHEELARAJAN R.S BHAVANAM,KARUVATTA NORTH 15 MOHANKUMAR(AYYAPPAN) MONEESHBHAVANAM,KARUVATTA 16 Sosamma Louis Chullikkal, Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 17 Jayamohan Shyama Nivas, Pollethai.P.O 18 Kala Thamarappallyveli,Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 19 Dinakaran Udamssery,Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 20 Rema Devi Puthenmadam, Kalvoor. P.O, Alappuzha 21 Indira Thilakan Pandyalakkal, Kalavoor. P.O, Alappuzha h 22 t V. Sethunath Kunnathu, Kalavoor. P.O, Alappuzha u o S 23 Reshmi Raju Rajammalayam, Pathirappally, Alappuzha m a l u k 24 i Muthulekshmi Castle, Pathirappaly.P.O, Alappuzha r a r a M 25 Thresyamma( Marykutty) Chavadiyil, Pathirappally, Alappuzha Page 1 Sheet1 h t u o S m a l u k i r a r a M 26 Philomina (Suja) Vadakkan parambil, Pathirappally, Alappuzha 27 Omana Moonnukandathil, Pathirappally. -

Indian History Ancient Indian History : General Facts About Indian Rulers and Historical Periods

Indian History Ancient Indian History : General Facts about Indian rulers and historical periods The Mauryan Empire (325 BC -183 BC) Chandragupta Maurya : In 305 BC Chandragupta defeated Seleucus Nikator, who surrendered a vast territory. Megasthenese was a Greek ambassador sent to the court of Chandragupta Maurya by Seleucus Bindusara: Bindusara extended the kingdom further and conquered the south as far as Mysore Asoka : (304– 232 BCE) Facts about Mauryas During Mauryan rule, though there was banking system in India. yet usury was customary and the rate of interest was 15’ /’ per annum on borrowing money. In less secure transactions (like sea Voyages etc) the rate of interest could be as high as 60 per annum. During Mauryan period, the punch marked coins (mostly of silver) were the common units of transactions. Megasthenes in his Indies had mentioned 7 castes in Mauryan society. They were philosophers, farmers, soldiers, herdsmen, artisans, magistrates and councilors. For latest updates : subscribe our Website - www.defenceguru.co.in The Age of the Guptas (320 AD-550 AD) Chandragupta I 320 - 335 AD Samudragupta 335-375 AD Ramagupta 375 - 380 AD Chandragupta Vikramaditya 380-413 AD Kumargupta Mahendraditya 415-455 AD Skandagupta 455-467 AD Later Guptas : Purugupia, Narasimhagupta, Baladitya. Kumargupta II, Buddhagupta, Bhanugupta, Harshagupta, Damodargupta, Mahasenagupta Literature : Authors and Book Bhasa -Svapanavasavdattam Shudrak -Mrichchakatika Amarkosh -Amarsimha Iswara Krishna -Sankhya Karika Vatsyana -Kama Sutra Vishnu (Gupta -Panchatantra Narayan Pandit -Hitopdesha For latest updates : subscribe our Website - www.defenceguru.co.in Bhattin -Ravan Vadha Bhaivi -Kiratarjunyam Dandin -Daskumarachanta Aryabhatta -Aryabhattyan Vishakha Datta -Mudura Rakshasa Indrabhuti -nanassiddhi Varahamihara -Panchasiddh antika, Brihad Samhita Kalidas : Kalidas wrote a number of such excellent dramas like Sakuntala, Malavikagnimitram, Vikrumorvasiyatn, epics like the Raghuvamsa, and lyric poetry like the Ritu-Samhara and the Meghaduta. -

Escholarship@Mcgill

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI" Modernity, Islamic Reform, and the Mappilas of Kerala: The Contributions of Vakkom Moulavi (1873-1932) Jose Abraham Institute of Islamic Studies McGiIl University, Montreal November, 2008 A thesis submitted to McGiIl University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ©Jose Abraham 2008 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et ?F? Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-66281-6 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-66281-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Muslim Entrepreneurs in Public Life Between India and the Gulf: Making Good and Doing Good

Muslim entrepreneurs in public life between India and the Gulf: making good and doing good Filippo Osella University of Sussex Caroline Osella School of Oriental and African Studies Muslim entrepreneurs from Kerala, South India, are at the forefront of India’s liberalizing economy, keen innovators who have adopted the business and labour practices of global capitalism in both Kerala and the Gulf. They are also heavily involved in both charity and politics through activity in Kerala’s Muslim public life. They talk about their ‘social mindedness’ as a combination of piety and economic calculation, the two seen not as excluding but reinforcing each other. By promoting modern education among Muslims, entrepreneurs seek to promote economic development while also embedding economic practices within a framework of ethics and moral responsibilities deemed to be ‘Islamic’. Inscribing business into the rhetoric of the ‘common good’ also legitimizes claims to leadership and political influence. Orientations towards self-transformation through education, adoption of a ‘systematic’ lifestyle, and a generalized rationalization of practices have acquired wider currency amongst Muslims following the rise of reformist influence and are now mobilized to sustain novel forms of capital accumulation. At the same time, Islam is called upon to set moral and ethical boundaries for engagement with the neoliberal economy. Instrumentalist analyses cannot adequately explain the vast amounts of time and money which Muslim entrepreneurs put into innumerable ‘social’ projects, and neither ‘political Islam’ nor public pietism adequately captures the possibilities or motivations for engagement among contemporary reformist-orientated Muslims. While historians have written extensively about the participation of elites in processes of social and religious reform in late colonial India (see, e.g., Gupta 2002; Joshi 2001; Robinson 1993 [1974]; Walsh 2004; cf. -

Ancestral Centers of Kerala Muslim Socio- Cultural and Educational Enlightenments Dr

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Ancestral Centers of Kerala Muslim Socio- Cultural and Educational Enlightenments Dr. A P Alavi Bin Mohamed Bin Ahamed Associate Professor of Islamic history Post Graduate and Research Department of Islamic History, Government College, Malappuram. Abstract: This piece of research paper attempts to show that the genesis and growth of Islam, a monotheistic religion in Kerala. Of the Indian states, Malabar was the most important state with which the Arabs engaged in trade from very ancient time. Advance of Islam in Kerala,it is even today a matter of controversy. Any way as per the established authentic historical records, we can definitely conclude that Islam reached Kerala coast through the peaceful propagation of Arab-Muslim traders during the life time of prophet Muhammad. Muslims had been the torch bearers of knowledge and learning during the middle ages. Traditional education centres, i.e Maqthabs, Othupallis, Madrasas and Darses were the ancestral centres of socio-cultural and educational enlightenments, where a new language, Arabic-Malayalam took its birth. It was widely used to impart educational process and to exhort anti-colonial feelings and religious preaching in Medieval Kerala. Keywords: Darses, Arabi-Malayalam, Othupalli, Madrasa. Introduction: Movements of revitalization, renewal and reform are periodically found in the glorious history of Islam since its very beginning. For higher religious learning, there were special arrangements in prominent mosques. In the early years of Islam, the scholars from Arab countries used to come here frequently and some of them were entrusted with the charges of the Darses, higher learning centres, one such prominent institution was in Ponnani.