Saving Galveston: a History of the Galveston Historical Foundation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18P-035 STF PKT.Pdf

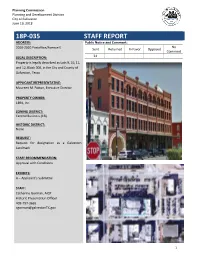

Planning Commission Planning and Development Division City of Galveston June 19, 2018 18P-035 STAFF REPORT ADDRESS: Public Notice and Comment: No 2010-2020 Postoffice/Avenue E Sent Returned In Favor Opposed Comment LEGAL DESCRIPTION: 34 Property is legally described as Lots 9, 10, 11, and 12, Block 500, in the City and County of Galveston, Texas APPLICANT/REPRESENTATIVE: Maureen M. Patton, Executive Director PROPERTY OWNER: 1894, Inc. ZONING DISTRICT: Central Business (CB) HISTORIC DISTRICT: None REQUEST: Request for designation as a Galveston Landmark STAFF RECOMMENDATION: Approval with Conditions EXHIBITS: A – Applicant’s Submittal STAFF: Catherine Gorman, AICP Historic Preservation Officer 409-797-3665 [email protected] 1 Zoning and Land Use Location Zoning Land Use Subject Central Business (CB) Commercial Site North Central Business (CB) Parking South Central Business (CB) Commercial East Central Business (CB) Commercial West Central Business (CB) Commercial Executive Summary The applicants are requesting designation of the above referenced address, as a Galveston Landmark. Analysis As per Article 10 of the Land Development Regulations, the following criteria should be considered during the Landmark Designation review process: 1. The character, interest, or value as part of the development, heritage, or cultural characteristics of the City of Galveston, Galveston County, the State of Texas, or the United States. The Grand Opera House and Hotel complex is valuable to the cultural heritage of the City of Galveston due to its association with the performing arts. Constructed in 1894, The Grand Opera House operated continuously, as both a live theater and a movie theater, until 1974. After an extensive restoration in the 1980s, the Grand Opera House continues as a setting for live performances, with more than 90,000 attendees a year. -

Salsa2bills 1..4

H.C.R.ANo.A117 HOUSE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION 1 WHEREAS, The history of Texas is not complete without 2 recognition of the ships, seaports, and maritime heritage that 3 contributed so greatly to the development, economy, immigration, 4 and culture of the state in the 19th century, and the state 's 5 preeminent symbol of this thrilling bygone era is the tall ship 6 Elissa; and 7 WHEREAS, In the 1970s, the city of Galveston was looking for a 8 ship to complement the restoration and redevelopment of the Strand, 9 known in the 1800s as the Wall Street of the South, and to help 10 Texans recognize and interpret the state 's maritime heritage; and 11 WHEREAS, Constructed in 1877 in Aberdeen, Scotland, Elissa is 12 a three-masted, iron-hulled tall ship of the "barque" type, 13 measuring 205 feet long and 99 feet, 9 inches high at the mainmast, 14 with a cargo capacity equivalent to that of eight railroad boxcars; 15 and 16 WHEREAS, Elissa transported a variety of goods around the 17 world over the course of her more than 90 years of commercial 18 history, first calling at Galveston in December 1883 with a cargo of 19 bananas and one passenger, then sailing for Liverpool, England, 20 with a cargo of cotton, and calling at Galveston again in September 21 1886 with a cargo of what was probably lumber or sugar and sailing 22 for Pensacola, Florida, in ballast; and 23 WHEREAS, Built at the dawn of the steamship era, Elissa 24 filled a niche in maritime commerce, calling on many ports, and she 1 H.C.R.ANo.A117 1 was sold from owner to owner, sailing -

2019 Holiday Programming.Pdf

PICK UP YOUR HOLIDAY BROCHURES AND POSTERS AT PARK BOARD PLAZA OR CALL 409.797.5151. November 15, 2019 - January 12, 2020 ONGOING HOLIDAY EVENTS AN EVENING WITH WILLIE CHARLES DICKENS’ A SANTA HUSTLE HALF NELSON & FAMILY AT THE CHRISTMAS CAROL AT THE MARATHON & 5K SANTA SIGHTINGS ISLAND ETC PRESENTS: A TUNA GRAND GRAND Dec 15 CHRISTMAS Nov 19 Dec 6 – 7 PHOTOS WITH SANTA AT Nov 8 – 30 THE 5 BROWNS – HOLIDAY AT MOODY GARDENS VIENNA BOYS CHOIR – VICTORIAN HOLIDAY HOMES THE GRAND Nov 16 – Dec 24 GALVESTON RAILROAD CHRISTMAS IN VIENNA AT THE TOUR Dec 21 MUSEUM PRESENTS THE POLAR GRAND Dec 6 SANTA AT THE GRAND 1894 EXPRESS™ TRAIN RIDE Nov 22 DON’T DROP THE BALL! NEW OPERA HOUSE (EDNA’S ROOM Nov 15 – Dec 29 PIPE ORGAN EXTRAVAGANZA AT YEAR’S CELEBRATION AT HOLIDAY ART MARKET) JASTON WILLIAMS IN BLOOD & TRINITY EPISCOPAL CHURCH ROSENBERG LIBRARY Nov 30 FREE HOLIDAY IN THE GARDENS HOLLY – CHRISTMAS WEST OF Dec 7 Dec 26 FREE Nov 16 – Jan 12 THE PECOS AT THE GRAND SUNDAY BRUNCH WITH SANTA OLIVER’S ALLEY, AT DICKEN’S RUDOLPH, THE RED-NOSED AT HOTEL GALVEZ MOODY GARDENS ICE LAND: Nov 23 – 24 ON THE STRAND SPONSORED REINDEER AT THE GRAND Dec 1, 8, 15 & 22 CHRISTMAS AROUND THE HOTEL GALVEZ HOLIDAY BY GALVESTON CHILDREN’S Dec 28 WORLD LIGHTING CELEBRATION MUSEUM FAMILY FREE NIGHT WITH Nov 16 – Jan 12 Nov 29 FREE Dec 7 – 8 HAPPY NEW YEAR, VIENNA SANTA AT THE GALVESTON STYLE! GALVESTON SYMPHONY CHILDREN’S MUSEUM MOODY GARDENS FESTIVAL ARTWALK FAMILY DAY AT THE OCEAN ORCHESTRA AT THE GRAND Dec 5 OF LIGHTS Nov 30 FREE STAR DRILLING RIG MUSEUM Jan 5 FREE Nov -

Galveston, Texas

Galveston, Texas 1 TENTATIVE ITINERARY Participants may arrive at beach house as early as 8am Beach geology, history, and seawall discussions/walkabout Drive to Galveston Island State Park, Pier 21 and Strand, Apffel Park, and Seawolf Park Participants choice! Check-out of beach house by 11am Activities may continue after check-out 2 GEOLOGIC POINTS OF INTEREST Barrier island formation, shoreface, swash zone, beach face, wrack line, berm, sand dunes, seawall construction and history, sand composition, longshore current and littoral drift, wavelengths and rip currents, jetty construction, Town Mountain Granite geology Beach foreshore, backshore, dunes, lagoon and tidal flats, back bay, salt marsh wetlands, prairie, coves and bayous, Pelican Island, USS Cavalla and USS Stewart, oil and gas drilling and production exhibits, 1877 tall ship ELISSA Bishop’s Palace, historic homes, Pleasure Pier, Tremont Hotel, Galveston Railroad Museum, Galveston’s Own Farmers Market, ArtWalk 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS • Barrier Island System Maps • Jetty/Breakwater • Formation of Galveston Island • Riprap • Barrier Island Diagrams • Town Mountain Granite (Galveston) • Coastal Dunes • Source of Beach and River Sands • Lower Shoreface • Sand Management • Middle Shoreface • Upper Shoreface • Foreshore • Prairie • Backshore • Salt Marsh Wetlands • Dunes • Lagoon and Tidal Flats • Pelican Island • Seawolf Park • Swash Zone • USS Stewart (DE-238) • Beach Face • USS Cavalla (SS-244) • Wrack Line • Berm • Longshore Current • 1877 Tall Ship ELISSA • Littoral Zone • Overview -

Historic Downtown Galveston Attractions

HISTORIC DOWNTOWN GALVESTON ATTRACTIONS Welcome to the Historic Downtown Strand Seaport District – a 70-block district located along Galveston Harbor just steps away from the Galveston Cruise Terminal. Once known as “The Wall Street of the South,” this charming historic district is famous for its majestic iron-front buildings that house unique boutiques, coastal-inspired art galleries, gift shops, museums, restaurants and other entertaining attractions. There is plenty to do and see! While you’re exploring, feel free to share with us on social media and don’t forget to tag our pages at Facebook.com/VisitGalvestonIsland and Twitter: @GalvestonIsland. PIER 21 AREA Texas Seaport Museum & 1877 Tall Ship ELISSA Share the adventure of the high seas at the Texas Seaport Museum, where you can tour the celebrated 1877 Tall Ship ELISSA. The museum also tells the story of seaborne commerce and immigration in Galveston, which was the second busiest immigration port in U.S. history. (Harborside Drive and 21st) www.galvestonhistory.org Pier 21 Theater Learn about Galveston’s fascinating history at the Pier 21 Theater, showing The Great Storm – a short documentary telling the story of Galveston’s recovery after the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history. The theater also shows The Pirate Island of Jean Lafitte and Galveston: Gateway on the Gulf. (Harborside Drive and 21st) www.galvestonhistory.org Historic Harbor Tour + Dolphin Watch Come aboard the Seagull II for sightings of the island’s playful dolphins and a view of the island from the sea on this exciting one-hour boat tour of Galveston’s harbor. -

Race and College Football in the Southwest, 1947-1976

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE DESEGREGATING THE LINE OF SCRIMMAGE: RACE AND COLLEGE FOOTBALL IN THE SOUTHWEST, 1947-1976 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By CHRISTOPHER R. DAVIS Norman, Oklahoma 2014 DESEGREGATING THE LINE OF SCRIMMAGE: RACE AND COLLEGE FOOTBALL IN THE SOUTHWEST, 1947-1976 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ____________________________ Dr. Stephen H. Norwood, Chair ____________________________ Dr. Robert L. Griswold ____________________________ Dr. Ben Keppel ____________________________ Dr. Paul A. Gilje ____________________________ Dr. Ralph R. Hamerla © Copyright by CHRISTOPHER R. DAVIS 2014 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements In many ways, this dissertation represents the culmination of a lifelong passion for both sports and history. One of my most vivid early childhood memories comes from the fall of 1972 when, as a five year-old, I was reading the sports section of one of the Dallas newspapers at my grandparents’ breakfast table. I am not sure how much I comprehended, but one fact leaped clearly from the page—Nebraska had defeated Army by the seemingly incredible score of 77-7. Wild thoughts raced through my young mind. How could one team score so many points? How could they so thoroughly dominate an opponent? Just how bad was this Army outfit? How many touchdowns did it take to score seventy-seven points? I did not realize it at the time, but that was the day when I first understood concretely the concepts of multiplication and division. Nebraska scored eleven touchdowns I calculated (probably with some help from my grandfather) and my love of football and the sports page only grew from there. -

FRIENDS of THC BOARD of DIRECTORS Name Address City State Zip Work Home Mobile Email Email Code Killis P

FRIENDS OF THC BOARD OF DIRECTORS Name Address City State Zip Work Home Mobile Email Email Code Killis P. Almond 342 Wilkens San TX 78210 210-532-3212 512-532-3212 [email protected] Avenue Antonio Peggy Cope Bailey 3023 Chevy Houston TX 77019 713-523-4552 713-301-7846 [email protected] Chase Drive Jane Barnhill 4800 Old Brenham TX 77833 979-836-6717 [email protected] Chappell Hill Road Jan Felts Bullock 3001 Gilbert Austin TX 78703 512-499-0624 512-970-5719 [email protected] Street Diane D. Bumpas 5306 Surrey Dallas TX 75209 214-350-1582 [email protected] Circle Lareatha H. Clay 1411 Pecos Dallas TX 75204 214-914-8137 [email protected] [email protected] Street Dianne Duncan Tucker 2199 Troon Houston TX 77019 713-524-5298 713-824-6708 [email protected] Road Sarita Hixon 3412 Houston TX 77027 713-622-9024 713-805-1697 [email protected] Meadowlake Lane Lewis A. Jones 601 Clark Cove Buda TX 78610 512-312-2872 512-657-3120 [email protected] Harriet Latimer 9 Bash Place Houston TX 77027 713-526-5397 [email protected] John Mayfield 3824 Avenue F Austin TX 78751 512-322-9207 512-482-0509 512-750-6448 [email protected] Lynn McBee 3912 Miramar Dallas TX 75205 214-707-7065 [email protected] [email protected] Avenue Bonnie McKee P.O. Box 120 Saint Jo TX 76265 940-995-2349 214-803-6635 [email protected] John L. Nau P.O. Box 2743 Houston TX 77252 713-855-6330 [email protected] [email protected] Virginia S. -

Houston-Galveston, Texas Managing Coastal Subsidence

HOUSTON-GALVESTON, TEXAS Managing coastal subsidence TEXAS he greater Houston area, possibly more than any other Lake Livingston A N D S metropolitan area in the United States, has been adversely U P L L affected by land subsidence. Extensive subsidence, caused T A S T A mainly by ground-water pumping but also by oil and gas extraction, O C T r has increased the frequency of flooding, caused extensive damage to Subsidence study area i n i t y industrial and transportation infrastructure, motivated major in- R i v vestments in levees, reservoirs, and surface-water distribution facili- e S r D N ties, and caused substantial loss of wetland habitat. Lake Houston A L W O Although regional land subsidence is often subtle and difficult to L detect, there are localities in and near Houston where the effects are Houston quite evident. In this low-lying coastal environment, as much as 10 L Galveston feet of subsidence has shifted the position of the coastline and A Bay T changed the distribution of wetlands and aquatic vegetation. In fact, S A Texas City the San Jacinto Battleground State Historical Park, site of the battle O Galveston that won Texas independence, is now partly submerged. This park, C Gulf of Mexico about 20 miles east of downtown Houston on the shores of Galveston Bay, commemorates the April 21, 1836, victory of Texans 0 20 Miles led by Sam Houston over Mexican forces led by Santa Ana. About 0 20 Kilometers 100 acres of the park are now under water due to subsidence, and A road (below right) that provided access to the San Jacinto Monument was closed due to flood- ing caused by subsidence. -

07-77817-02 Final Report Dickinson Bayou

Dickinson Bayou Watershed Protection Plan February 2009 Dickinson Bayou Watershed Partnership 1 PREPARED IN COOPERATION WITH TEXAS COMMISSION ON ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY AND U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY The preparation of this report was financed though grants from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency through the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................................ 7 LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................................. 8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................. 9 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 10 SUMMARY OF MILESTONES ........................................................................................................................ 13 FORWARD ................................................................................................................................................... 17 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................... 18 The Dickinson Bayou Watershed .................................................................................................................. -

Debra Maceo Work Phone (409) 740-4915 PO Box 1675 Galveston, TX 77553 Education: B.S. Health & Physical Education, Lamar Un

VITA Debra Maceo Work Phone (409) 740-4915 PO Box 1675 Galveston, TX 77553 Education: B.S. Health & Physical Education, Lamar University, 1975 M.Ed. Physical Education with a concentration in Dance, University of Houston, 1995 Certification: Lifetime Teacher Certification, Health, Physical Education and Dance YogaFit Teacher Training Program, Level 1, Level 2 and Level 3 Zumba Instructor Certification First Responder Training/AED/CPR , Recertification 2013 Teaching Experience: Texas A&M University at Galveston Instructional Professor Instructional Associate Professor, 2012-present Senior Lecturer, Physical Education Program, 2003-2012 Fulltime Lecturer, Physical Education Program, 1995-2002 Part time Lecturer, Physical Education Program, 1994 Texas City High School, Texas City, Texas Dance instructor/Dance Team Director/Health & Physical Education instructor, 1979-1994 Created and implemented Texas Education Agency approved curriculum for Dance Education Choreographed and directed performances; winning sweepstakes and choreography awards Directed/choreographed numerous stage productions Carolyn Ehman’s Dance Academy, Galveston, Texas Assistant instructor/choreographer, 1990-2001 St. Patrick’s Catholic School, Galveston, Texas Physical Education instructor Created the Private Elementary School Basketball League Honors and Awards The Association of Former Students Distinguished Achievement Award for Student Relationships, University Level, 2012 SALT Camp Namesake; Camp Maceo 2011 The Association of Former Students Distinguished -

The Ghostly-Silent Guns of Galveston: a Chronicle of Colonel J.G

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 33 Issue 2 Article 7 10-1995 The Ghostly-Silent Guns of Galveston: A Chronicle of Colonel J.G. Kellersberger, the Confederate Chief Engineer of East Texas W. T. Block Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Block, W. T. (1995) "The Ghostly-Silent Guns of Galveston: A Chronicle of Colonel J.G. Kellersberger, the Confederate Chief Engineer of East Texas," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 33 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol33/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORlCAL ASSOCIATION THE GHOSTLY·SILENT GUNS OF GALVESTON: A CHRONICLE OF COLONEL J.G. KELLERSBERGER, THE CONFEDERATE CHIEF ENGINEER OF EAST TEXAS by WT. Block Tn 1896, as wintry blasts swept down the valley of the River Aare in northern Switzerland, an old man consumed endless hours in his ancestral home, laboring to complete a manuscript. With his hair and beard as snow capped as the neighboring Alpine peaks, Julius Getulius Kellersberger, who felt that life was fast ebbing from his aging frame, wrote and rewrote each page with an engineer~s masterful precision, before shipping the finished version of his narrative to Juchli and Beck, book publishers of Zurich.] After forty-nine years in America, Kellersberger, civil engineer, former Forty-oiner, San Francisco Vigilante, surveyor~ town, bridge, and railroad builder; and Confederate chief engineer for East Texas, bade farewell to a son and four daughters, his grandchildren~ and the grave of his wife, all located at Cypress Mill, Blanco County, Texas. -

Chief Financial Officer

“Your Co-Workers on the Island” Chief Financial Officer The Board employs 301 team members to include 104 full-time staff, with additional seasonal employees as needed, and manages an operational budget of more than $18 million with 13 unique funds, including Beach Maintenance, Beach Patrol, East End Lagoon, Tourism Development, Beach Parks, Dellanera RV Park, Seawolf Park, and Administration. The Park Board of Trustees also operates and manages Seawall Parking and the collection of hotel occupancy taxes (HOT). This budget provides for the continuation of current and new programs and also includes FEMA-Hurricane Ike-Harvey recovery revenue and expenditures for ongoing rebuilding projects. For more information on the Galveston Island Park Board of GALVESTON ISLAND Trustees, please visit: https://www.galvestonparkboard.org/. Galveston Island is a historic beach town on the southeast coast of Texas and the Gulf of Mexico, just 50 miles from Houston and home ACOUNTING DEPARTMENT to just over 50,000 people. Best known as one of the top beach The mission of the Park Board’s Accounting Department is to destinations, the 32 miles long and 2.5 miles wide island is fortunate maintain accurate financial information and internal controls. The to have a diverse economic base anchored by maritime, healthcare, Department is responsible for all of the Board’s financial activities education, tourism, and has positioned itself as a vital component to including and not limited to: preparation of the operations the economic engine of the Texas Gulf Coast. Galveston Island offers budget, accounts receivable, accounts payable, purchase orders/ a rich history, culture, natural amenities, and boutique shopping.