Some Notes on Leaves of Memory, the Autobiography of Hermann Kobold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ocabulary of Definitions : P

Service bibliothèque Catalogue historique de la bibliothèque de l’Observatoire de Nice Source : Monographie de l’Observatoire de Nice / Charles Garnier, 1892. Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur Février 2012 Présentation << On trouve… à l’Ouest … la bibliothèque avec ses six mille deux cents volumes et ses trentes journaux ou recueils périodiques…. >> (Façade principale de la Bibliothèque / Phot. attribuée à Michaud A. – 188? - Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur) C’est en ces termes qu’Henri Joseph Anastase Perrotin décrivait la bibliothèque de l’Observatoire de Nice en 1899 dans l’introduction du tome 1 des Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice 1. Un catalogue des revues et ouvrages 2 classé par ordre alphabétique d’auteurs et de lieux décrivait le fonds historique de la bibliothèque. 1 Introduction, Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice publiés sous les auspices du Bureau des longitudes par M. Perrotin. Paris,Gauthier-Villars,1899, Tome 1,p. XIV 2 Catalogue de la bibliothèque, Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice publiés sous les auspices du Bureau des longitudes par M. Perrotin. Paris,Gauthier-Villars,1899, Tome 1,p. 1 Le présent document est une version remaniée, complétée et enrichie de ce catalogue. (Bibliothèque, vue de l’intérieur par le photogr. Jean Giletta, 191?. - Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur) Chaque référence est reproduite à l’identique. Elle est complétée par une notice bibliographique et éventuellement par un lien électronique sur la version numérisée. Les titres et documents non encore identifiés sont signalés en italique. Un index des auteurs et des titres de revues termine le document. -

A Handbook of Double Stars, with a Catalogue of Twelve Hundred

The original of this bool< is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924064295326 3 1924 064 295 326 Production Note Cornell University Library pro- duced this volume to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. It was scanned using Xerox soft- ware and equipment at 600 dots per inch resolution and com- pressed prior to storage using CCITT Group 4 compression. The digital data were used to create Cornell's replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Stand- ard Z39. 48-1984. The production of this volume was supported in part by the Commission on Pres- ervation and Access and the Xerox Corporation. Digital file copy- right by Cornell University Library 1991. HANDBOOK DOUBLE STARS. <-v6f'. — A HANDBOOK OF DOUBLE STARS, WITH A CATALOGUE OF TWELVE HUNDRED DOUBLE STARS AND EXTENSIVE LISTS OF MEASURES. With additional Notes bringing the Measures up to 1879, FOR THE USE OF AMATEURS. EDWD. CROSSLEY, F.R.A.S.; JOSEPH GLEDHILL, F.R.A.S., AND^^iMES Mt^'^I^SON, M.A., F.R.A.S. "The subject has already proved so extensive, and still ptomises so rich a harvest to those who are inclined to be diligent in the pursuit, that I cannot help inviting every lover of astronomy to join with me in observations that must inevitably lead to new discoveries." Sir Wm. Herschel. *' Stellae fixac, quae in ccelo conspiciuntur, sunt aut soles simplices, qualis sol noster, aut systemata ex binis vel interdum pluribus solibus peculiari nexu physico inter se junccis composita. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Nachlass EDUARD SCHÖNFELD (1828-1891) Inhaltsverzeichnis Bearbeitet von Anne Hoffsümmer und Lea Korb Bonn, 2017 – 2018 zuletzt aktualisiert am 09.09.2020 Eduard Schönfeld wurde am 22.12.1828 in Hildburghausen geboren, wo er bis zu seinem Abitur 1847 die Schule besuchte. Er war Kind einer jüdischen Familie, trat jedoch nach seinem Schulabschluss dem evangelischen Glauben bei. Auf Anraten seines Vaters studierte Schönfeld zunächst Bauwesen, entschied sich aber nach kurzer Zeit für die Naturwissenschaften und begann, in Marburg bei dem Gauß-Schüler Christian Ludwig Gerling unter anderem Astronomie zu studieren. Nachdem Schönfeld auf einer Reise nach Bonn Bekanntschaft mit Friedrich Wilhelm August Argelander gemacht hatte, entschloss er sich, das Studium der Astronomie 1852 in Bonn fortzusetzen. Dort erhielt er schon ein Jahr später eine Stelle als Assistent, durch die er die Möglichkeit erhielt, gemeinsam mit Adalbert Krüger an der bekannten „Bonner Durchmusterung“, Argelanders großem Projekt, mitzuwirken. Mit einer Abhandlung über die Bahnelemente des Kleinplaneten Thetis promovierte Schönfeld 1854. Seine Habilitation folgte drei Jahre später. Eduard Schönfeld zog 1859 nach Mannheim, um dort die Stelle als Direktor der Mannheimer Sternwarte anzutreten. In der Mannheimer Zeit widmete er sich unter anderem der Bestimmung der Positionen von Nebelflecken mithilfe des Ringmikrometer. Eduard Schönfeld war Mitbegründer und Vorstandsmitglied der Astronomischen Gesellschaft sowie lange Jahre ihr Schriftführer und Herausgeber der Vierteljahrsschrift. Nach Argelanders Tod im Jahr 1875 übernahm Schönfeld dessen Stelle als Direktor der Bonner Sternwarte und ergänzte die Arbeit zur Bonner Durchmusterung, indem er die Bereiche -2°- -23° der südlichen Deklination erforschte. 1883 wurde er Geheimer Regierungsrat und war 1887/88 Rektor der Universität Bonn. -

Tales from the Nineteenth-Century Archives

Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Studies 12 Lorraine Daston: The Accidental Trace and the Science of the Future: Tales from the Nineteenth- Century Archives In: Julia Bärnighausen, Costanza Caraffa, Stefanie Klamm, Franka Schneider, and Petra Wodtke (eds.): Photo-Objects : On the Materiality of Photographs and Photo Archives Online version at http://mprl-series.mpg.de/studies/12/ ISBN 978-3-945561-39-3 First published 2019 by Edition Open Access, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. Printed and distributed by: PRO BUSINESS digital printing Deutschland GmbH, Berlin http://www.book-on-demand.de/shop/15803 The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de Chapter 4 The Accidental Trace and the Science of the Future: Tales from the NineteenthCentury Archives Lorraine Daston Introduction: glass and paper forever This glass photographic plate of a small square of the night sky, taken on a clear winter’s night in Potsdam in 1894, is one of the around two million such astrophotographic plates stored in observatories all over the world (Lankford 1984, 29) (see Fig. 1). There are ap proximately 600,000 plates at the Harvard College Observatory, 20,000 at the Bologna Uni versity Observatory, 80,000 at the Odessa Astronomical Observatory, to give just a few examples (Hudec 1999). The designation of these collections as “archives” is mostly ret rospective, but the glass plate pictured here was destined from the outset to be part of an archive: the vast astrophotographic survey of the sky as seen from the earth known as the Carte du Ciel. -

9781402036439.Pdf

THE MULTINATIONAL HISTORY OF STRASBOURG ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATORY ASTROPHYSICS AND SPACE SCIENCE LIBRARY VOLUME 330 EDITORIALBOARD Chairman W.B. BURTON, National Radio Astronomy Observatory, Charlottesville, Virginia, U.S.A. ([email protected]); University of Leiden, The Netherlands ([email protected]) Executive Committee J. M. E. KUIJPERS, University of Nijmegen, The Netherlands E. P. J. VAN DEN HEUVEL, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands H. VAN DER LAAN, University of Utrecht, The Netherlands MEMBERS J. N. BAHCALL, The Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, U.S.A. F. BERTOLA, University of Padua, Italy J. P. CASSINELLI, University of Wisconsin, Madison, U.S.A. C. J. CESARSKY, European Southern Observatory, Garching bei München, Germany O. ENGVOLD, University of Oslo, Norway A. HECK, Strasbourg Astronomical Observatory, France R. McCRAY, University of Colorado, Boulder, U.S.A. P. G. MURDIN, Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge, U.K. F. PACINI, Istituto Astronomia Arcetri, Firenze, Italy V. RADHAKRISHNAN, Raman Research Institute, Bangalore, India K. SATO, School of Science, The University of Tokyo, Japan F. H. SHU, University of California, Berkeley, U.S.A. B. V. SOMOV, Astronomical Institute, Moscow State University, Russia R. A. SUNYAEV, Space Research Institute, Moscow, Russia Y. TANAKA, Institute of Space & Astronautical Science, Kanagawa, Japan S. TREMAINE, Princeton University, U.S.A. N. O. WEISS, University of Cambridge, U.K. THE MULTINATIONAL HISTORY OF STRASBOURG ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATORY Edited by ANDRÉ H CK Observatoire Astronomique, Strasbourg, France A C.I.P. Catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 10 1-4020-3643-4 (HB) ISBN 13 978-1-4020-3643-9 (HB) ISBN 10 1-4020-3644-2 (e-book) ISBN 13 978-1-4020-3644-6 (e-book) Published by Springer, P.O. -

Commerzbank Aktiengesellschaft

Commerzbank Aktiengesellschaft Head-office: Kaiserplatz, 60261 Frankfurt am Main, Germany German Stock Corporation Registered Share Capital: EUR 1.556.326.015,40 Commercial Registry Number: HRB 32 000 ANNUAL REPORT 2004 INDEX SECTION 1 ANNUAL REPORT ...............................................................................................................................................1 BALANCE SHEET.............................................................................................................................................95 STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY .................................................................................................................96 CHANGES IN MINORITY INTERESTS ....................................................................................................................97 CASH FLOW STATEMENT .................................................................................................................................98 NOTES..........................................................................................................................................................100 AUDITOR’S REPORT ......................................................................................................................................183 SUPERVISORY BOARD REPORT......................................................................................................................184 SECTION 2 INDIVIDUAL ACCOUNTS OF COMMERZBANK AG...............................................................................................223 -

Sternwarte Online.Pdf (4.371Mb)

Klaus Beuermann (Hg.) Grundsätze über die Anlage neuer Sternwarten Georg Heinrich Borheck Erschienen im Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2005 Klaus Beuermann (Hg.) Grundsätze über die Anlage neuer Sternwarten unter Beziehung auf die Sternwarte der Universität Göttingen von Georg Heinrich Borheck Mit einem Geleitwort des Präsidenten der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Kurt von Figura und Beiträgen von David Aubin, Klaus Beuermann, Robert Förster, Christian Freigang und Nicolaas Rupke, Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2005 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.ddb.de> abrufbar. © Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2005 Bearbeitet von der Niedersächsischen Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen Abbildungsnachweis: Universitäts-Sternwarte Göttingen: 6, 7, 8, 10, 15, 16, 20, 21, 22, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34. K. Reinsch, Universitäts-Sternwarte: 1, 9, 11, 12, 13, 25. R. Förster: 17, 18, 19. Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen: 4, 5, 23. Privatbesitz: 2, 3, 14. Digitalisierungen: Göttinger Digitalisierungszentrum an der Niedersächsischen Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen Umschlaggestaltung: Margo Bargheer Satz und Layout: Universitätsverlag Göttingen ISBN 3-938616-02-4 Inhaltsverzeichnis Kurt von Figura Geleitwort des Präsidenten ...................................................................................................................... -

Karl Schwarzschild (1873-1916) Klaus Reinsch Und Axel D

arl Schwarzschild (1873–1916) gilt weltweit als einer der begabtesten und bedeutendsten Astronomen aller Zeiten und als Mitbegründer der Astrophysik.K Geboren in Frankfurt am Main, wirkte er von 1901 bis 1909 Karl Schwarzschild als Professor für Astronomie und Direktor der Sternwarte in Göttingen (1873-1916) und von 1909 bis 1916 als Direktor des Astrophysikalischen Observato- riums in Potsdam. Im Laufe seines allzu kurzen Lebens veröffentlichte Schwarzschild etwa Ein Pionier und Wegbereiter 150 wissenschaftliche Arbeiten, viele davon von fundamentaler Bedeu- tung für die Entwicklung der Astronomie und Astrophysik. der Astrophysik Aus Anlass seines 100. Todestages fand am 19. Mai 2016 in einer sei- ner früheren Wirkungsstätten, der heutigen Historischen Sternwarte in Herausgegeben von Klaus Reinsch Göttingen, ein Gedenk-Kolloquium statt. Die schriftlichen Fassungen der dabei gehaltenen Vorträge sind, ergänzt um einen am 8. September und Axel D. Wittmann 2016 anlässlich der Eröffnung der Schwarzschild-Ausstellung in der Fakultät für Physik gehaltenen Vortrag, im vorliegenden Band abgedruckt. Klaus Reinsch und Axel D. Wittmann (Hg.) Karl Schwarzschild (1873-1916) Klaus Reinsch und Axel D. Wittmann (Hg.) Karl Schwarzschild ISBN: 978-3-86395-295-2 Universitätsverlag Göttingen Universitätsverlag Göttingen Klaus Reinsch und Axel D. Wittmann (Hg.) Karl Schwarzschild (1873-1916) Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung - Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International Lizenz. erschienen im Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2017 Klaus Reinsch und Axel D. Wittmann (Hg.) Karl Schwarzschild (1873-1916) Ein Pionier und Wegbereiter der Astrophysik Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2017 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.dnb.de> abrufbar. -

Biographical Memoir of Asaph Hall*

BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR ASAPH HALL 1829-1907 GEORGE WILLIAM HILL READ HEI-OIIK THE NATION.\I, ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AI-KH> 2:>, loos (25) 241 BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF ASAPH HALL* Tn commencing the story of a remarkable man of science, it is necessary to say something of his lineage, in spite of the gener- ally held opinion that the details of genealogy make dry read- ing, f ASAPH HALL undoubtedly descended from John Hall, called of New Haven and Wallingford to distinguish him from the other numerous John Halls of early New England (Savage makes no less than seven before 1660), and who arrived at New Haven shortly after June 4, 1639, as he is one of the after-signers of tlie New Haven Planters' Covenant. His movements before his arrival are in some obscurity. From his son Thomas of Wal- lingford receiving a grant of fifty acres of land from the General Court of the Colony at the session of October, 1698, "In consid- eration of his father's services in the Pequot war," it is inferred that he was a dweller in the colony in 1637. At this date there were only four settlements in Connecticut, and it is supposed that the John Hall of New Haven is identical with a John Hall who appears as the holder of lots in Hartford about 1635. The genealogists arc in dispute in the matter. Mr. Shepard sums up thus: John Hall came with the advance Hooker party, in 1632, or perhaps on the Griffin or the Bird (two vessels whose arrival at Massachusetts Bay is mentioned by Winthrop), September 4, 1633. -

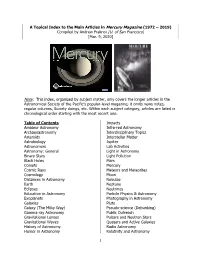

A Topical Index to the Main Articles in Mercury Magazine (1972 – 2019) Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U

A Topical Index to the Main Articles in Mercury Magazine (1972 – 2019) Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U. of San Francisco) [Mar. 9, 2020] Note: This index, organized by subject matter, only covers the longer articles in the Astronomical Society of the Pacific’s popular-level magazine; it omits news notes, regular columns, Society doings, etc. Within each subject category, articles are listed in chronological order starting with the most recent one. Table of Contents Impacts Amateur Astronomy Infra-red Astronomy Archaeoastronomy Interdisciplinary Topics Asteroids Interstellar Matter Astrobiology Jupiter Astronomers Lab Activities Astronomy: General Light in Astronomy Binary Stars Light Pollution Black Holes Mars Comets Mercury Cosmic Rays Meteors and Meteorites Cosmology Moon Distances in Astronomy Nebulae Earth Neptune Eclipses Neutrinos Education in Astronomy Particle Physics & Astronomy Exoplanets Photography in Astronomy Galaxies Pluto Galaxy (The Milky Way) Pseudo-science (Debunking) Gamma-ray Astronomy Public Outreach Gravitational Lenses Pulsars and Neutron Stars Gravitational Waves Quasars and Active Galaxies History of Astronomy Radio Astronomy Humor in Astronomy Relativity and Astronomy 1 Saturn Sun SETI Supernovae & Remnants Sky Phenomena Telescopes & Observatories Societal Issues in Astronomy Ultra-violet Astronomy Solar System (General) Uranus Space Exploration Variable Stars Star Clusters Venus Stars & Stellar Evolution X-ray Astronomy _______________________________________________________________________ Amateur Astronomy Hostetter, D. Sidewalk Astronomy: Bridge to the Universe, 2013 Winter, p. 18. Fienberg, R. & Arion, D. Three Years after the International Year of Astronomy: An Update on the Galileoscope Project, 2012 Autumn, p. 22. Simmons, M. Sharing Astronomy with the World [on Astronomers without Borders], 2008 Spring, p. 14. Williams, L. Inspiration, Frame by Frame: Astro-photographer Robert Gendler, 2004 Nov/Dec, p. -

Sirius Brightest Diamond in the Night Sky Jay B

Sirius Brightest Diamond in the Night Sky Jay B. Holberg Sirius Brightest Diamond in the Night Sky Published in association with 4y Sprringei i Praxis Publishing Chichester, UK Dr Jay B. Holberg Senior Research Scientist Lunar and Planetary Laboratory University of Arizona Tucson Arizona U.S.A. SPRINGER-PRAXIS BOOKS IN POPULAR ASTRONOMY SUBJECT ADVISORY EDITOR: John Mason B.Sc, M.Sc, Ph.D. ISBN 10: 0-387-48941-X Springer Berlin Heidelberg New York ISBN 13: 978-0-387-48941-4 Springer Berlin Heidelberg New York Springer is part of Springer-Science + Business Media (springer.com) Library of Congress Control Number: 2006938990 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. © Praxis Publishing Ltd, Chichester, UK, 2007 Printed in Germany The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Cover design: Jim Wilkie Project management: Originator Publishing Services, -

THE THIRD REDUCTION of GIUSEPPE PIAZZI's STAR CATALOGUE Abstract

THE THIRD REDUCTION OF GIUSEPPE PIAZZI'S STAR CATALOGUE E. Proverbio Astronomical Observatory - Cagliari, Italy Abstract The star observations carried out by Giuseppe Piazzi with Rams- den's large altazimuth circle, which he began in 1792, led to the rea- lization of a 1st and 2nd Catalogue, published by Piazzi in Palermo in 1803 and 1814. During 1845, the original astronomical observations in Piazzi's catalogue, included in "La storia celeste of the Palermo Observatory from 1792 to 1814", which had been kept at the Brera Observatory in Milan, were published in Vienna. The publication of these observational data revealed a series of errors, real or presumed, which cast doubt on the reliability of the Palermo Catalogue. Towards the end of the last century, upon the suggestion of Gio- vanni Schiaparelli, work on the reduction of Piazzi's catalogue was once again taken up for the purpose of producing an independent cata- logue based on the original observations. This work, carried out by Francesco Porro, led to the production of a corrected catalogue purged of systematic and accidental errors. The third fundamental star catalogue of Palermo may represent the basis for the final reduction of the great Palermo Catalogue of 7646 stars. G. Piazzi's 1st and 2nd Catalogues In the second half of the 18th century, if we exclude Tobias Ma- yer's brilliant activity, positional astronomy and research for the realization of fixed star catalogues were basically dominated by the English and French schools. It is no accident that Giuseppe Piaz- zi(l), during his visit to France and England between 1787 and 1789 for the purpose of improving his knowledge in the field of practical astronomy commissioned the famous Ramsden to build for him a 5 foot 75 S.