Tales from the Nineteenth-Century Archives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amédée Ernest Barthémy MOUCHEZ

Astronomía Latinoamericana Amédée Ernest Barthémy MOUCHEZ Un almirante que se las trajo en la región. Edgardo Ronald Minniti Morgan Premio H.C. Pollock 2005 Miembro de la Red Mundial de Escritores en Español Integrante del Grupo de Investigación en Enseñanza, Difusión, e Historia de la Astronomía, del Observatorio de Córdoba-UNC – historiadelaastronomía.wordpress.com – HistoLIADA – Lidea Amédée Ernest Barthémy Mouchez. Unos de los casos más notables de la astronomía decimonónica, que afectó profundamente la evolución de esa ciencia en Latinoamérica y en el mundo, fue el devenido almirante francés Amédée Ernest Barthémy Mouchez. Español, de padres franceses, nació en Madrid el 24 de Agosto de 1821. Adoptó de muy joven la carrera marítima, ingresando en los cuerpos de la marina francesa, cuya nacionalidad adoptó, destacándose por su dedicación e inteligencia. Se especializó en geodesia astronómica aplicada a la hidrografía naval; actividad que le permitió alcanzar con honores el grado de Capitán de Navío en el año 1868. Durante varios años recorrió las costas de América, desde Panamá hasta el Río de la Plata, efectuando relevamientos cartográficos de trascendente importancia. 1846 Carta Esférica de una parte de la Bahía de Panamá que comprende el puerto de Sta. Bárbara- detalle - Web Como teniente de navío Mouchez permaneció cuatro años con el Aviso de su mando “Bisson” en las aguas del Plata y sus afluentes, destacando – por ejemplo en sus informes – haber notado una gran baja del nivel de las aguas en Octubre de 1856 y una crecida extraordinaria en Mayo de 1858, las cuales, observadas en la escala de mareas, que tenía puesta en el puerto de Paraná, dieron por diferencia de niveles la notable cifra de 5m 24cm, conforme es destacado en el “Manual de la navegación del Rí , según los documentos mas fidedignos, nacionales y extranjeros”, elaborado por los señores Lobo y Riudavets. -

Transferencia De Conocimientos Hidrográficos Y Astronómicos Entre Francia Y Argentina. La Construcción De Paisajes Marítimos

Transferencia de conocimientos hidrográficos y astronómicos entre Francia y Argentina. La construcción de paisajes marítimos y portuarios Miguel de Marco (h), Nathan Godet, Helen Mair Rawsthorne To cite this version: Miguel de Marco (h), Nathan Godet, Helen Mair Rawsthorne. Transferencia de conocimientos hidro- gráficos y astronómicos entre Francia y Argentina. La construcción de paisajes marítimos y portuarios. 2020. hal-02975592 HAL Id: hal-02975592 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02975592 Preprint submitted on 22 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Transferencia de conocimientos hidrográficos y astronómicos entre Francia y Argentina. La construcción de paisajes marítimos y portuarios. De Marco (h), Miguel Ángel*, Godet, Nathan y Rawsthorne, Helen*** * Instituto de Estudios Históricos, Económicos Sociales e Internacionales del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas de la República Argentina, [email protected] ** Centre de Recherche Interdisciplinaire en Histoire, Histoire de l’art et Musicologie (Criham, EA 4270), Université de Poitiers, et le Centre François Viète (EA 1161), Université de Bretagne Occidentale, [email protected] *** Centre François Viète (EA 1161), Université de Bretagne Occidentale, [email protected] Resumen El Servicio Hidrográfica y Oceanográfica de la Marina de Francia (Shom), con sede en la ciudad de Brest, desde hace 300 años atesora uno de los repositorios documentales más importantes en su temática. -

A Handbook of Double Stars, with a Catalogue of Twelve Hundred

The original of this bool< is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924064295326 3 1924 064 295 326 Production Note Cornell University Library pro- duced this volume to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. It was scanned using Xerox soft- ware and equipment at 600 dots per inch resolution and com- pressed prior to storage using CCITT Group 4 compression. The digital data were used to create Cornell's replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Stand- ard Z39. 48-1984. The production of this volume was supported in part by the Commission on Pres- ervation and Access and the Xerox Corporation. Digital file copy- right by Cornell University Library 1991. HANDBOOK DOUBLE STARS. <-v6f'. — A HANDBOOK OF DOUBLE STARS, WITH A CATALOGUE OF TWELVE HUNDRED DOUBLE STARS AND EXTENSIVE LISTS OF MEASURES. With additional Notes bringing the Measures up to 1879, FOR THE USE OF AMATEURS. EDWD. CROSSLEY, F.R.A.S.; JOSEPH GLEDHILL, F.R.A.S., AND^^iMES Mt^'^I^SON, M.A., F.R.A.S. "The subject has already proved so extensive, and still ptomises so rich a harvest to those who are inclined to be diligent in the pursuit, that I cannot help inviting every lover of astronomy to join with me in observations that must inevitably lead to new discoveries." Sir Wm. Herschel. *' Stellae fixac, quae in ccelo conspiciuntur, sunt aut soles simplices, qualis sol noster, aut systemata ex binis vel interdum pluribus solibus peculiari nexu physico inter se junccis composita. -

NEWSLETI'er September-October 1987 PRESIDENT's REPORT Although I Am Writing This Report in the Dog Days of Summer, Most of Us Wi

Volume 17, Number 5 NEWSLETI'ER September-October 1987 PRESIDENT'S REPORT Although I am writing this report in the dog days of summer, most of us will be back to the rigors of our respective positions by the time this Newsletter appears. For many mathematicians, fall carries the additional responsibility of preparing grant proposals (I understand there are some very organized individuals who do this in the summer). I urge our women and minority members to bear in mind the many grants available through the ROW (Research Opportunities for Women) and Minority programs at the National Science Foundation. A thorough description of these opportunities is given in the article by Louise Raphael in this Newsletter (May-June 1987). One of the most attractive of the NSF offerings is the Visiting Professorships for Women program. I have spoken to many women who have received this grant or applied for it, and was surprised to learn that there is a wide variety of opinion regarding its efficacy. If you have had experience with this grant or have an opinion about the concept, I would appreciate hearing your views. While on the subject of the NSF, I would like to take this opportunity to wish Dr. Kenneth Gross, who has been the Program Director for Modern Analysis for the past two years, best of luck as he leaves NSF for the University of Vermont. Dr. Gross has been a strong supporter of women and minority mathematicians while at NSF, and many women have commented on the encouragement he has given them. * Linda Keen and I have written to the Notices regarding the lack of women speakers at the symposium on the mathematical heritage of Hermann Weyl at Duke University (see August Notices, Letters to the Editor). -

MACHIELS, André Travailleur Bénévole À L'observatoire De Paris À Partir De 1930, Il Collabora Avec Mineur Dès 1932

MACHIELS, André Travailleur bénévole à l'Observatoire de Paris à partir de 1930, il collabora avec Mineur dès 1932. Il fut conduit, en rentrant de captivité, à cesser son activité astronomique. - Sur la répartition des aplatissements des nébuleuses elliptiques (Bulletin astronomique 6 (2), 317, 1930) ; - Classification des nébuleuses extragalactiques par leurs formes. Amas de Coma–Virgo (Bulletin astronomique 6 (2), 405, 1930) ; - Sur la distribution de la matière absorbante galactique (avec Mineur, CRAS 195, 1234,1932) ; - A propos d'une explication des vitesses d'éloignement des nébuleuses (CRAS 197, 1025, 1933) ; - Classification, formes et orientations des nébuleuses extragalactiques (Bulletin astronomique 9 (2), 471, 1934) ; - Remarque au sujet des effets qui résultent, d'après H.J. Gramatzki, d'une variation de la vitesse de la lumière avec le temps (ZfA 9, 329, 1935) - A propos d'un critérium de la réalité des vitesses de nébuleuses (CRAS 204, 1708, 1937). MACRET, J.D. J.D. Macret a publié : Découverte du vrai principe astronomique, translation du soleil (l’auteur, Paris, 1879). (Blavier, 1982) MACRIS, Constantin De nationalité grecque, il vint en 1947 à l'observatoire de Meudon pour commencer une thèse sur la granulation solaire avec Lyot. Il a probablement (?) soutenu sa thèse en 1953 à Paris : Recherches sur la granulation photosphérique (Annales d'astrophysique 16, 19, 1953). Il était en 1991 professeur à l'université d'Athènes. (Olivieri, 1993) MAERLEYN Il fut calculateur (ou agent administratif ?) à l'Observatoire de Paris de juillet 1855 à septembre 1859. (AN:F17.3733) MAES, Louis Joseph (1815-1898) Louis Joseph Maës est né à Paris le 28 mai 1815. -

The Important Role of the Two French Astronomers J.-N. Delisle and J.-J. Lalande in the Choice of Observing Places During the Transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769

MEETING VENUS C. Sterken, P. P. Aspaas (Eds.) The Journal of Astronomical Data 19, 1, 2013 The Important Role of the Two French Astronomers J.-N. Delisle and J.-J. Lalande in the Choice of Observing Places during the Transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769 Simone Dumont1 and Monique Gros2 1Observatoire de Paris, 61 Avenue de l’Observatoire, 75014, Paris, France 2Observatoire de Paris, Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris – Universit´e Pierre et Marie Curie, 98 bis Boulevard Arago, 75014, Paris, France Abstract. Joseph-Nicolas Delisle, as a member of the Acad´emie Royale des Sci- ences of Paris and professor at the Coll`ege Royal de France, went to England in 1724 to visit Newton and Halley. The latter suggested observations of the transits of Mercury and of Venus in order to obtain the solar parallax. Delisle was also in- terested in the Mercury transits. After a stay of 22 years in Saint Petersburg, on his return to Paris, he distributed avertissements (information bulletins) encouraging all astronomers to observe the same phenomena, like the solar eclipse of 1748. Later, in 1760, Delisle presented an Adresse to the King and to the Acad´emie in which he detailed his method to observe the 1761 transit of Venus. This was accompanied by a mappemonde showing the best places for observations. Copies of the text, together with 200 maps, were sent to his numerous correspondents in France and abroad. Following the advanced age and finally death of Delisle, his assistant and successor Joseph-J´erˆome Lalande presented a m´emoire related to the 1769 transit of Venus and an improved map of the best observing places. -

Diffusion Et Mutation Des Méthodes De L'astronomie Nautique, 1749-1905

Diffusion et mutation des méthodes de l’astronomie nautique, 1749-1905 Guy Boistel To cite this version: Guy Boistel. Diffusion et mutation des méthodes de l’astronomie nautique, 1749-1905 : Accompagné du mémoire d’habilitation, “ Une école pratique d’astronomie au service des marins et des explorateurs : l’observatoire de la Marine et du Bureau des longitudes au parc Montsouris, 1875-1914 ”. Histoire, Philosophie et Sociologie des sciences. Université de Nantes, 2010. tel-01341041 HAL Id: tel-01341041 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01341041 Submitted on 3 Jul 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITÉ DE NANTES Habilitation à diriger des recherches Diffusion et mutation des méthodes de l’astronomie nautique, 1749-1905 Accompagné du mémoire d’habilitation , « Une école pratique d’astronomie au service des marins et des explorateurs : l’observatoire de la Marine et du Bureau des longitudes au parc Montsouris, 1875-1914 » par Guy BOISTEL 2010 VOLUME 1 Parcours de recherche, Curriculum Vitæ et publications représentatives des travaux de recherches Dossier scientifique constitué en vue de l’obtention du diplôme d’H.D.R. vendredi 12 mars 2010 Habilitation à diriger des recherches Vol . -

Cahiers François Viete

CAHIERS FRANÇOIS VIETE Série I – N°11-12 2006 L’événement astronomique du siècle ? Histoire sociale des passages de Vénus, 1874-1882 DAVID AUBIN - L'événement astronomique du siècle ? Une histoire sociale des passages de Vénus, 1874-1882 JIMENA CANALES - Sensational differences: the case of the transit of Venus STÉPHANE LE GARS - Image et mesure : deux cultures aux origines de l'astrophysique française JESSICA RATCLIFF - Models, metaphors, and the transit of Venus at Victorian Greenwich RICHARD STALEY - Conspiracies of Proof and Diversity of Judgement in Astronomy and Physics: On Physicists' Attempts to Time Light's Wings and Solve Astronomy's Noblest Problem LAETITIA MAISON - L'expédition à Nouméa : l'occasion d'une réflexion sur l'astronomie française GUY BOISTEL - Des bras de Vénus aux fauteuils de l'Académie, ou comment le passage de Vénus permit à Ernest Mouchez de devenir le premier marin directeur de l'Observatoire de Paris MARTINA SCHIAVON - Astronomie de terrain entre Académie des sciences et Armée SIMON WERRETT - Transits and transitions: astronomy, topography, and politics in Russian expeditions to view the transit of Venus in 1874 DAVID AUBIN ET COLETTE LE LAY - Bibliographie générale Centre François Viète Épistémologie, histoire des sciences et des techniques Université de Nantes Achevé d'imprimer sur les presses de l'imprimerie centrale de l'université de Nantes, juillet 2017 Mise en ligne en juin 2018 sur www.cfv.univ-nantes.fr SOMMAIRE • DAVID AUBIN ......................................................................................................... 3 L'événement astronomique du siècle ? Une histoire sociale des passages de Vénus, 1874-1882 • JIMENA CANALES ................................................................................................. 15 Sensational differences: the case of the transit of Venus • STÉPHANE LE GARS ............................................................................................ -

L'annuaire Du Bureau Des Longitudes (1795

Collection du Bureau des longitudes Volume 8 Colette Le Lay L’Annuaire du Bureau des longitudes (1795 - 1932) Collection du Bureau des longitudes - Volume 8 Colette Le Lay Bureau des longitudes © Bureau des longitudes, 2021 ISBN : 978-2-491688-05-9 ISSN : 2724-8372 Préface C’est avec grand plaisir que le Bureau des longitudes accueille dans ses éditions l’ouvrage de Colette Le Lay consacré à l’Annuaire du Bureau des longitudes. L’Annuaire est la publication du Bureau destinée aux institutions nationales, aux administrations1 et au grand public, couvrant, selon les époques, des domaines plus étendus que l’astronomie, comme la géographie, la démographie ou la physique par exemple. Sa diffusion est par nature plus large que celle des éphémérides et des Annales, ouvrages spécialisés destinés aux professionnels de l’astronomie ou de la navigation. De fait l’Annuaire est sans aucun doute la publication du Bureau la plus connue du public et sa parution régulière repose sur les bases légales de la fondation de l’institution lui enjoignant de présenter chaque année au Corps Législatif un Annuaire propre à régler ceux de toute la République. L’ouvrage de Mme Le Lay couvre l’histoire de l’Annuaire sur la période allant de la création du Bureau des longitudes en 1795 jusqu’à 1932. L’auteure nous décrit les évolutions de son contenu au cours du temps, les acteurs qui le réalisent et ses utilisateurs. On y verra que les changements ont été grands entre l’opuscule hésitant de ses débuts, qui se limitait à quelques renseignements astronomiques sur les levers-couchers du Soleil et de la Lune, les éclipses et déjà les poids et mesures, et les imposants volumes du XIXe siècle avec des tables de toutes natures et des notices scientifiques étoffées. -

Biographical Memoir of Asaph Hall*

BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR ASAPH HALL 1829-1907 GEORGE WILLIAM HILL READ HEI-OIIK THE NATION.\I, ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AI-KH> 2:>, loos (25) 241 BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF ASAPH HALL* Tn commencing the story of a remarkable man of science, it is necessary to say something of his lineage, in spite of the gener- ally held opinion that the details of genealogy make dry read- ing, f ASAPH HALL undoubtedly descended from John Hall, called of New Haven and Wallingford to distinguish him from the other numerous John Halls of early New England (Savage makes no less than seven before 1660), and who arrived at New Haven shortly after June 4, 1639, as he is one of the after-signers of tlie New Haven Planters' Covenant. His movements before his arrival are in some obscurity. From his son Thomas of Wal- lingford receiving a grant of fifty acres of land from the General Court of the Colony at the session of October, 1698, "In consid- eration of his father's services in the Pequot war," it is inferred that he was a dweller in the colony in 1637. At this date there were only four settlements in Connecticut, and it is supposed that the John Hall of New Haven is identical with a John Hall who appears as the holder of lots in Hartford about 1635. The genealogists arc in dispute in the matter. Mr. Shepard sums up thus: John Hall came with the advance Hooker party, in 1632, or perhaps on the Griffin or the Bird (two vessels whose arrival at Massachusetts Bay is mentioned by Winthrop), September 4, 1633. -

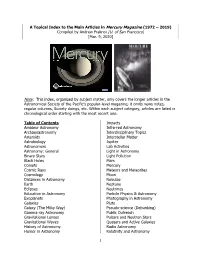

A Topical Index to the Main Articles in Mercury Magazine (1972 – 2019) Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U

A Topical Index to the Main Articles in Mercury Magazine (1972 – 2019) Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U. of San Francisco) [Mar. 9, 2020] Note: This index, organized by subject matter, only covers the longer articles in the Astronomical Society of the Pacific’s popular-level magazine; it omits news notes, regular columns, Society doings, etc. Within each subject category, articles are listed in chronological order starting with the most recent one. Table of Contents Impacts Amateur Astronomy Infra-red Astronomy Archaeoastronomy Interdisciplinary Topics Asteroids Interstellar Matter Astrobiology Jupiter Astronomers Lab Activities Astronomy: General Light in Astronomy Binary Stars Light Pollution Black Holes Mars Comets Mercury Cosmic Rays Meteors and Meteorites Cosmology Moon Distances in Astronomy Nebulae Earth Neptune Eclipses Neutrinos Education in Astronomy Particle Physics & Astronomy Exoplanets Photography in Astronomy Galaxies Pluto Galaxy (The Milky Way) Pseudo-science (Debunking) Gamma-ray Astronomy Public Outreach Gravitational Lenses Pulsars and Neutron Stars Gravitational Waves Quasars and Active Galaxies History of Astronomy Radio Astronomy Humor in Astronomy Relativity and Astronomy 1 Saturn Sun SETI Supernovae & Remnants Sky Phenomena Telescopes & Observatories Societal Issues in Astronomy Ultra-violet Astronomy Solar System (General) Uranus Space Exploration Variable Stars Star Clusters Venus Stars & Stellar Evolution X-ray Astronomy _______________________________________________________________________ Amateur Astronomy Hostetter, D. Sidewalk Astronomy: Bridge to the Universe, 2013 Winter, p. 18. Fienberg, R. & Arion, D. Three Years after the International Year of Astronomy: An Update on the Galileoscope Project, 2012 Autumn, p. 22. Simmons, M. Sharing Astronomy with the World [on Astronomers without Borders], 2008 Spring, p. 14. Williams, L. Inspiration, Frame by Frame: Astro-photographer Robert Gendler, 2004 Nov/Dec, p. -

Sirius Brightest Diamond in the Night Sky Jay B

Sirius Brightest Diamond in the Night Sky Jay B. Holberg Sirius Brightest Diamond in the Night Sky Published in association with 4y Sprringei i Praxis Publishing Chichester, UK Dr Jay B. Holberg Senior Research Scientist Lunar and Planetary Laboratory University of Arizona Tucson Arizona U.S.A. SPRINGER-PRAXIS BOOKS IN POPULAR ASTRONOMY SUBJECT ADVISORY EDITOR: John Mason B.Sc, M.Sc, Ph.D. ISBN 10: 0-387-48941-X Springer Berlin Heidelberg New York ISBN 13: 978-0-387-48941-4 Springer Berlin Heidelberg New York Springer is part of Springer-Science + Business Media (springer.com) Library of Congress Control Number: 2006938990 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. © Praxis Publishing Ltd, Chichester, UK, 2007 Printed in Germany The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Cover design: Jim Wilkie Project management: Originator Publishing Services,