The Venus Transit 2004 the 1882 Transit of Venus As Seen from Chile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modelling and the Transit of Venus

Modelling and the transit of Venus Dave Quinn University of Queensland <[email protected]> Ron Berry University of Queensland <[email protected]> Introduction enior secondary mathematics students could justifiably question the rele- Svance of subject matter they are being required to understand. One response to this is to place the learning experience within a context that clearly demonstrates a non-trivial application of the material, and which thereby provides a definite purpose for the mathematical tools under consid- eration. This neatly complements a requirement of mathematics syllabi (for example, Queensland Board of Senior Secondary School Studies, 2001), which are placing increasing emphasis on the ability of students to apply mathematical thinking to the task of modelling real situations. Success in this endeavour requires that a process for developing a mathematical model be taught explicitly (Galbraith & Clatworthy, 1991), and that sufficient opportu- nities are provided to students to engage them in that process so that when they are confronted by an apparently complex situation they have the think- ing and operational skills, as well as the disposition, to enable them to proceed. The modelling process can be seen as an iterative sequence of stages (not ) necessarily distinctly delineated) that convert a physical situation into a math- 1 ( ematical formulation that allows relationships to be defined, variables to be 0 2 l manipulated, and results to be obtained, which can then be interpreted and a n r verified as to their accuracy (Galbraith & Clatworthy, 1991; Mason & Davis, u o J 1991). The process is iterative because often, at this point, limitations, inac- s c i t curacies and/or invalid assumptions are identified which necessitate a m refinement of the model, or perhaps even a reassessment of the question for e h t which we are seeking an answer. -

Lomonosov, the Discovery of Venus's Atmosphere, and Eighteenth Century Transits of Venus

Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 15(1), 3-14 (2012). LOMONOSOV, THE DISCOVERY OF VENUS'S ATMOSPHERE, AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURY TRANSITS OF VENUS Jay M. Pasachoff Hopkins Observatory, Williams College, Williamstown, Mass. 01267, USA. E-mail: [email protected] and William Sheehan 2105 SE 6th Avenue, Willmar, Minnesota 56201, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The discovery of Venus's atmosphere has been widely attributed to the Russian academician M.V. Lomonosov from his observations of the 1761 transit of Venus from St. Petersburg. Other observers at the time also made observations that have been ascribed to the effects of the atmosphere of Venus. Though Venus does have an atmosphere one hundred times denser than the Earth’s and refracts sunlight so as to produce an ‘aureole’ around the planet’s disk when it is ingressing and egressing the solar limb, many eighteenth century observers also upheld the doctrine of cosmic pluralism: believing that the planets were inhabited, they had a preconceived bias for believing that the other planets must have atmospheres. A careful re-examination of several of the most important accounts of eighteenth century observers and comparisons with the observations of the nineteenth century and 2004 transits shows that Lomonosov inferred the existence of Venus’s atmosphere from observations related to the ‘black drop’, which has nothing to do with the atmosphere of Venus. Several observers of the eighteenth-century transits, includ- ing Chappe d’Auteroche, Bergman, and Wargentin in 1761 and Wales, Dymond, and Rittenhouse in 1769, may have made bona fide observations of the aureole produced by the atmosphere of Venus. -

History of Science Society Annual Meeting San Diego, California 15-18 November 2012

History of Science Society Annual Meeting San Diego, California 15-18 November 2012 Session Abstracts Alphabetized by Session Title. Abstracts only available for organized sessions. Agricultural Sciences in Modern East Asia Abstract: Agriculture has more significance than the production of capital along. The cultivation of rice by men and the weaving of silk by women have been long regarded as the two foundational pillars of the civilization. However, agricultural activities in East Asia, having been built around such iconic relationships, came under great questioning and processes of negation during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as people began to embrace Western science and technology in order to survive. And yet, amongst many sub-disciplines of science and technology, a particular vein of agricultural science emerged out of technological and scientific practices of agriculture in ways that were integral to East Asian governance and political economy. What did it mean for indigenous people to learn and practice new agricultural sciences in their respective contexts? With this border-crossing theme, this panel seeks to identify and question the commonalities and differences in the political complication of agricultural sciences in modern East Asia. Lavelle’s paper explores that agricultural experimentation practiced by Qing agrarian scholars circulated new ideas to wider audience, regardless of literacy. Onaga’s paper traces Japanese sericultural scientists who adapted hybridization science to the Japanese context at the turn of the twentieth century. Lee’s paper investigates Chinese agricultural scientists’ efforts to deal with the question of rice quality in the 1930s. American Motherhood at the Intersection of Nature and Science, 1945-1975 Abstract: This panel explores how scientific and popular ideas about “the natural” and motherhood have impacted the construction and experience of maternal identities and practices in 20th century America. -

The Concordiensis, Volume 1, Number 3

THE CONCORDIENSIS. VoL. I. ScHENECTADY, N. Y., January, 1878. No.3· UNION UNIVERSITY. REV. E. N. POTTER, D. D., PRESIDENT. UNION COLLEGE, DEPARTMENT OF MEDICINE. ALBANY MEDICAl: CoLLEGE.-Term commences First Tuesday in SCHENECTADY, N. Y. September and contmues twenty weeks. The plan of instruction combines clinical teaching, With lectures. Special opportunities for -0- the study of chemistry and of practical anatomy. ExPE!\s:Es.-Matriculation fee, $s. Term fee, $IOo. Perpetual the I. CLASSICAL CouRsE.-The Classical Course is the usual bacca Ticket, $rso. Graduation fee, $25. Dissecting fee, $s. Fee for labora laureate course of American colleges. Students may be permitted to tory course, $ro. Histological course, $ro. For Circulars, address, ding pursue additional studies in either of the other courses. PROF. JACOBs. MOS~ER, M.D., REGISTRAR, . z. .SciENTIFIC CouRSE.-ln the Scientific Course the modern lan Albany, N. Y. guages are substituted for the ancient, and the amount .of mathematical DEPARTMENT OF LAW. and English studies is increased. 3· SCHOOL OF CIVIL ENGINEERING.-The student in this depart THE ALEANY LAw ScHOOL.-The Course of Instruction consists of T, ment enjoys advantages nowhere surpassed, in the course of instruc three terms: the fin;t commencing September 4th, the Second N ovem tion, in its collectiOn of ·models, instruments and books, the ber 27th, and the third i\iarch sth; each term consisting of twelve 'endent. accumulations of many years by the late Professor Gillespie, and also weeks. The advantages for the study ot the l~w, at Albany, are as in unusal facilities for acquiring a practical knowledge of instrumental great as can be found anywhere. -

A Handbook of Double Stars, with a Catalogue of Twelve Hundred

The original of this bool< is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924064295326 3 1924 064 295 326 Production Note Cornell University Library pro- duced this volume to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. It was scanned using Xerox soft- ware and equipment at 600 dots per inch resolution and com- pressed prior to storage using CCITT Group 4 compression. The digital data were used to create Cornell's replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Stand- ard Z39. 48-1984. The production of this volume was supported in part by the Commission on Pres- ervation and Access and the Xerox Corporation. Digital file copy- right by Cornell University Library 1991. HANDBOOK DOUBLE STARS. <-v6f'. — A HANDBOOK OF DOUBLE STARS, WITH A CATALOGUE OF TWELVE HUNDRED DOUBLE STARS AND EXTENSIVE LISTS OF MEASURES. With additional Notes bringing the Measures up to 1879, FOR THE USE OF AMATEURS. EDWD. CROSSLEY, F.R.A.S.; JOSEPH GLEDHILL, F.R.A.S., AND^^iMES Mt^'^I^SON, M.A., F.R.A.S. "The subject has already proved so extensive, and still ptomises so rich a harvest to those who are inclined to be diligent in the pursuit, that I cannot help inviting every lover of astronomy to join with me in observations that must inevitably lead to new discoveries." Sir Wm. Herschel. *' Stellae fixac, quae in ccelo conspiciuntur, sunt aut soles simplices, qualis sol noster, aut systemata ex binis vel interdum pluribus solibus peculiari nexu physico inter se junccis composita. -

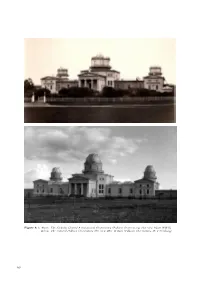

(Pulkovo Observatory) (The View Before WWII) Below: the Restored Pulkovo Observatory (The View After WWII) (Pulkovo Observatory, St

Figure 6.1: Above: The Nicholas Central Astronomical Observatory (Pulkovo Observatory) (the view before WWII) Below: The restored Pulkovo Observatory (the view after WWII) (Pulkovo Observatory, St. Petersburg) 60 6. The Pulkovo Observatory on the Centuries’ Borderline Viktor K. Abalakin (St. Petersburg, Russia) in Astronomy” presented in 1866 to the Saint-Petersburg Academy of Sciences. The wide-scale astrophysical studies were performed at Pulkovo Observatory around 1900 during the directorship of Theodore Bredikhin, Oscar Backlund and Aristarchos Be- lopolsky. The Nicholas Central Astronomical Observatory at Pulkovo, now the Central (Pulkovo) Astronomical Observatory of the Russian Academy of Sciences, had been co-founded by Friedrich Georg Wilhelm Struve (1793–1864) [Fig. 6.2] together with the All-Russian Emperor Nicholas the First [Fig. 6.3] and inaugurated in 1839. The Observatory had been erected on the Pulkovo Heights (the Pulkovo Hill) near Saint-Petersburg in ac- cordance with the design of Alexander Pavlovich Brül- low, [Fig. 6.3] the well-known architect of the Russian Empire. [Fig. 6.4: Plan of the Observatory] From the very beginning, the traditional field of re- search work of the Observatory was Astrometry – i. e. determination of precise coordinates of stars from the observations and derivation of absolute star catalogues for the epochs of 1845.0, 1865.0 and 1885.0 (the later catalogues were derived for epochs of 1905.0 and 1930.0); they contained positions of 374 through 558 bright, so- called fundamental, stars. It is due to these extraordi- Figure 6.2: Friedrich Georg Wilhelm (Vasily Yakovlevich) narily precise Pulkovo catalogues that Benjamin Gould Struve (1793–1864), director 1834 to 1862 had called the Pulkovo Observatory the “astronomical (Courtesy of Pulkovo Observatory, St. -

This Is an Electronic Reprint of the Original Article. This Reprint May Differ from the Original in Pagination and Typographic Detail

This is an electronic reprint of the original article. This reprint may differ from the original in pagination and typographic detail. Author(s): Sterken, Christiaan; Aspaas, Per Pippin; Dunér, David; Kontler, László; Neul, Reinhard; Pekonen, Osmo; Posch, Thomas Title: A voyage to Vardø - A scientific account of an unscientific expedition Year: 2013 Version: Please cite the original version: Sterken, C., Aspaas, P. P., Dunér, D., Kontler, L., Neul, R., Pekonen, O., & Posch, T. (2013). A voyage to Vardø - A scientific account of an unscientific expedition. The Journal of Astronomical Data, 19(1), 203-232. http://www.vub.ac.be/STER/JAD/JAD19/jad19.htm All material supplied via JYX is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, and duplication or sale of all or part of any of the repository collections is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for your research use or educational purposes in electronic or print form. You must obtain permission for any other use. Electronic or print copies may not be offered, whether for sale or otherwise to anyone who is not an authorised user. MEETING VENUS C. Sterken, P. P. Aspaas (Eds.) The Journal of Astronomical Data 19, 1, 2013 A Voyage to Vardø. A Scientific Account of an Unscientific Expedition Christiaan Sterken1, Per Pippin Aspaas,2 David Dun´er,3,4 L´aszl´oKontler,5 Reinhard Neul,6 Osmo Pekonen,7 and Thomas Posch8 1Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium 2University of Tromsø, Norway 3History of Science and Ideas, Lund University, Sweden 4Centre for Cognitive Semiotics, Lund University, Sweden 5Central European University, Budapest, Hungary 6Robert Bosch GmbH, Stuttgart, Germany 7University of Jyv¨askyl¨a, Finland 8Institut f¨ur Astronomie, University of Vienna, Austria Abstract. -

The Venus Transit: a Historical Retrospective

The Venus Transit: a Historical Retrospective Larry McHenry The Venus Transit: A Historical Retrospective 1) What is a ‘Venus Transit”? A: Kepler’s Prediction – 1627: B: 1st Transit Observation – Jeremiah Horrocks 1639 2) Why was it so Important? A: Edmund Halley’s call to action 1716 B: The Age of Reason (Enlightenment) and the start of the Industrial Revolution 3) The First World Wide effort – the Transit of 1761. A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 4) The Second Try – the Transit of 1769. A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 5) The 19th Century attempts – 1874 Transit A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 6) The 19th Century’s Last Try – 1882 Transit - Photography will save the day. A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 7) The Modern Era A: Now it’s just for fun: The AU has been calculated by other means). B: the 2004 and 2012 Transits: a Global Observation C: My personal experience – 2004 D: the 2004 and 2012 Transits: a Global Observation…Cont. E: My personal experience - 2012 F: New Science from the Transit 8) Conclusion – What Next – 2117. Credits The Venus Transit: A Historical Retrospective 1) What is a ‘Venus Transit”? Introduction: Last June, 2012, for only the 7th time in recorded history, a rare celestial event was witnessed by millions around the world. This was the transit of the planet Venus across the face of the Sun. -

Tales from the Nineteenth-Century Archives

Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Studies 12 Lorraine Daston: The Accidental Trace and the Science of the Future: Tales from the Nineteenth- Century Archives In: Julia Bärnighausen, Costanza Caraffa, Stefanie Klamm, Franka Schneider, and Petra Wodtke (eds.): Photo-Objects : On the Materiality of Photographs and Photo Archives Online version at http://mprl-series.mpg.de/studies/12/ ISBN 978-3-945561-39-3 First published 2019 by Edition Open Access, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. Printed and distributed by: PRO BUSINESS digital printing Deutschland GmbH, Berlin http://www.book-on-demand.de/shop/15803 The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de Chapter 4 The Accidental Trace and the Science of the Future: Tales from the NineteenthCentury Archives Lorraine Daston Introduction: glass and paper forever This glass photographic plate of a small square of the night sky, taken on a clear winter’s night in Potsdam in 1894, is one of the around two million such astrophotographic plates stored in observatories all over the world (Lankford 1984, 29) (see Fig. 1). There are ap proximately 600,000 plates at the Harvard College Observatory, 20,000 at the Bologna Uni versity Observatory, 80,000 at the Odessa Astronomical Observatory, to give just a few examples (Hudec 1999). The designation of these collections as “archives” is mostly ret rospective, but the glass plate pictured here was destined from the outset to be part of an archive: the vast astrophotographic survey of the sky as seen from the earth known as the Carte du Ciel. -

Estudios Sobre Cometas Realizados Desde Argentina

Estudios sobre cometas realizados desde Argentina Santiago Paolantonio Premio Hebert C. Pollock 2005 Coordinador Sección Historia de la Astronomía - LIADA [email protected] http://historiadelaastronomia.wordpress.com/ Conferencia dada el 9 de octubre de 2010, en oportunidad del 4to Simposio Iberoamericano de Cometas de la LIADA, Complejo Astronómico Municipal "Galileo Galilei" Parque Urquiza, Rosario, Argentina. Antecedentes Primer registro de la observación de un cometa Los grandes y brillantes cometas difícilmente pueden pasar desapercibidos, por lo que seguramente antes de la llegada de los europeos a Sudamérica, los habitantes originarios observaron estos astros. Sin embargo, aún no se tienen registros que lo atestigüen. La primera referencia con que se cuenta sobre la observación de un cometa desde estas regiones se remonta al siglo XVIII, cuando Diego de Alvear y Ponce de León ¡ jefe de la segunda comisión enviada desde Europa para la demarcación de límites entre los territorios de España y Portugal ¡ observó el 11 de enero de 1784 desde el hoy Uruguay un: “cometa caudatorio hacia la constelación austral de la Grulla. Su diámetro aparente se manifestaba como una estrella de segunda magnitud, y la cola inclinada a la parte opuesta del Sol aparecía bajo la proyección de un ángulo de dos grados… Notamos su movimiento al NNO, de la cantidad de grado y medio, en 24 horas” (Alvear, 1837) A partir de esta escueta cita, el autor ha podido determinar que el objeto mencionado fue el “Gran cometa” – C/1783 X1 –, descubierto independientemente por varios observadores. El primero en verlo fue el francés La Nux, el 15 de diciembre de 1873, desde la Diego de Alvear isla Bourbon en pleno Océano Índico. -

The Concordiensis, Volume 18, Number 4

' '. \folu~e X\f III. NOVEMBER 7, 1894.. ~, T-~H,' K' 7~ ,Q d JP .. 3@fl:~'=:CONTENTS~@~·>== - 0 ~AGE PAGE .ol1'rapl1I'a.s of 011·· r Trustees 3 _A1nusements .. , ................................ 10 Bl <J ~ ~. •••••••••••••••••••• Fraternity Initiations....... 4 · The Freshmen's Banquet. ........ 11 Sjxtie1b Annual Convention of Delta Upsilon.. 4 ~e first Junior Hop ............. _. ............. 11 West Point vs. Union.......................... 5 ·union's Class in Geology ....................... 12 . .·~.. Williams vs. Union............................ 6 The' Foot Ball Player .......................... 12 ·- Cross Country Ru.n.s . 7 Local and Personal. ............................ 12 Editorial.. • . s · Alumni Allusions ..............-. 14 Here and There ................................... 10 O·bituary · · · · · ................................... 16 The Garnet the Color we Love......... : ....... 10 , . '· t I - . Unio11 U n1vers1ty~ ® ·oo.·• 1 oo·-·.•• • ~i· ANDRE"\V V. V. RAYMOND,. D. D., LL, D., Presicl«,m:t. ----~-------------~----~--~--~----~ lfNION.-OOLLEGE, SCHENECTADY, N.Y. r 1' 1. Course Leading· to the Deg·ree of A. B.-The usual Classical Covrse, including ;French and German. After second term Junior ; the work is largely elective. 2. Co'tll'Se Leading to the Deg1•ee of B. S.-The mode11n languages are substituted .for the ancient and the amount of Mathematical and English studies is increased. 3. Courses Lea<Ung· to the DegTee of Ph. B. : 'j Cou.I·se A-Includes Mathematics and German of the B.S. Course, and the French and four terms of the Latin of the A. B. Course. Coru·se B-Indudes three terms of French, and all the German of B.S. Course, and Latin and Mathematics of A. B. Course. Cou.1·se C-Includes Latin, French and Mathematics of A. -

The Concordiensis, Volume 1, Number 2

THE S, CONCORDIENSIS. VoL. I. ScHENECTADY, N. Y., DEcEMBER, 1877. No. 2. :s, UNION UNIVERSITY. REV. E. N. POTTER, D. D., PRESIDENT. UNION COLLEGE, DEPAR.TMENT OF MEDICINE. ALBANY MEDICA~ CoLLEGE.-Termcommences First Tuesday in ScHENECTADY, N. Y. Septe~nber ~~d c-ontml!es twenty weeks. The plan of instruction combmes cl~mcal !eachmg, w1th le~tures. Special opportunities for -o- the study of chemistry and of practical anatomy. ExPEt\SEs.-Matriculation fee, $s. Term fee, $roo. Perpetual , 1. CLASSICAL CouRsE.-The Classical Course is the usual bacca Ticket, $rso. Graduation fee, $25. Dissecting fee, $5. Fee for labora the laureate course of American coHeges. Students may be permitted to tory course, $ro. I Iistological course, $w. For Circulars, address, pursue additional studies in either of the other courses. PROF. JACOBs. MOSHER, M.D., REGISTRAR, ling 2, SciENTIFIC CouRSE.-ln th.e Scientific Course the modern lan Albany, N. Y. guages are substituted for the ancient, and the amount of mathematical DEPARTMENT OF LAW. and English studies is increased. 3· SCHOOL OF (.iiVIL ENGINEERING.-The student iH this depart THE ALBANY LAw ScHooL.-The Course of Instruction consists of ment enjoys advantages nowhere surpassed, in the course of instruc three terms: the first commencing September 4th, the Second N overn tion, in its collectiOn of models, instruments and books, the ber 27th, and the third March sth ; each term consisting of twelve accumulations of many years by the late Professor Gillespie, and also weeks. The advantages for the study ot the law, at Albany, are as ~dent. in unusal facilities for acquiring a practical knowledge of instrumental great as can be found anywhere.