Fourth Amendment “Papers” and the Third-Party Doctrine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strange Bedfellows: Network Neutrality‘S Unifying Influence†

STRANGE BEDFELLOWS: NETWORK NEUTRALITY‘S UNIFYING INFLUENCE† Marvin Ammori* I want to talk about something called network (or ―net‖) neutrality. Let me begin, though, with a story involving short codes. For those unfamiliar with what a short code is, recall the voting process on American Idol and the little code that you can punch into your cell phone to vote for your favorite singer.1 Short codes are not ten digit numbers; rather, they are more like five or six.2 In theory, anyone can get a short code. Presidential candidates use short codes in their campaigns to communicate with their followers. For instance, a person could have signed up and Barack Obama would have sent them a message through a short code when he chose Joe Biden as his running mate.3 A few years ago, an abortion rights group called NARAL Pro-Choice America wanted a short code to communicate with its own followers.4 NARAL‘s goal was not to send ―spam‖; instead, the short code was directed to people who agreed with their message.5 Verizon rejected the idea of a short code for this group because, according to Verizon, NARAL was engaged in ―controversial‖ speech. The New York Times printed a front page article about this.6 Many people who read the story wondered if they really needed a permission slip from Verizon, or from anyone else, to communicate about political things that they care about. In response † This speech is adapted for publication and was originally presented at a panel discussion as part of the Regent University Law Review and The Federalist Society for Law & Public Policy Studies Media and Law Symposium at Regent University School of Law, October 9–10, 2009. -

How to Fix Legal Scholarmush

Indiana Law Journal Volume 95 Issue 4 Article 4 Fall 2020 How to Fix Legal Scholarmush Adam Kolber Brooklyn Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, Legal Profession Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Kolber, Adam (2020) "How to Fix Legal Scholarmush," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 95 : Iss. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol95/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How to Fix Legal Scholarmush ADAM J. KOLBER Legal scholars often fail to distinguish descriptive claims about what the law is from normative claims about what it ought to be. The distinction couldn’t be more important, yet scholars frequently mix it up, leading them to mistake legal authority for moral authority, treat current law as a justification for itself, and generally use rhetorical strategies more appropriate for legal practice than scholarship. As a result, scholars sometimes talk past each other, generating not scholarship but “scholarmush.” In recent years, legal scholarship has been criticized as too theoretical. When it comes to normative scholarship, however, the criticism is off the mark. We need more careful attention to theory, otherwise we’re left with what we have too much of now: claims with no solid normative grounding that amount to little more than opinions. -

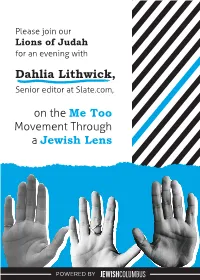

Dahlia Lithwick Invite Draft5

Please join our Lions of Judah for an evening with Dahlia Lithwick, Senior editor at Slate.com, on the Me Too Movement Through a Jewish Lens POWERED BY Dahlia Lithwick is a senior editor at Slate, and in that capacity, has been writing their “Supreme Court Dispatches” and “Jurisprudence” columns since 1999. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Harper’s, The New Yorker, The Washington Post, The New Republic, and Commentary, among other places. She is host of Amicus, Slate’s award-winning biweekly podcast about the law and the Supreme Court. She was Newsweek’s legal columnist from 2008 until 2011. Ms. Lithwick speaks frequently on the subjects of criminal justice reform, reproductive freedom, and religion in the courts. She has appeared on CNN, ABC, The Colbert Report, the Daily Show and is a frequent guest on The Rachel Maddow Show. She has testified before Congress about access to justice in the era of the Roberts Court. Ms. Lithwick earned her BA in English from Yale University and her JD degree from Stanford University. JewishColumbus’s Lion of Judah Society (LOJ) was established to provide women an opportunity to engage with their peers and increase their impact with a collective voice. Lions are women who make leadership gifts, as individuals or as part of a family gift, of $5,000 or more through JewishColumbus’s Annual Campaign. Lion of Judah dinner featuring Dahlia Lithwick, Thursday, June 4 The Terrace 711 North High Street, Columbus, OH 43215 Free valet parking Tickets: $50 each Link TBD Please RSVP by May 18 Dietary restrictions observed, catering provided by Cameron Mitchell Women’s Philanthropy Co-Chairs Jane Bodner & Emily Kandel Lion of Judah Co-Chairs Gigi Fried & Shelly Igdaloff Lion Event Co-Chairs Margie Goldach & Clemy Keidan Questions? Please contact Rachel Gleitman, Director of Women’s Philanthropy at [email protected] This event is open to Lions of Judah and Step Up Lions. -

The Lost Nuance of Big Data Policing

THE LOST NUANCE OF BIG DATA POLICING 94 TEX. L. REV. __ (forthcoming 2015) Jane Bambauer* The third party doctrine permits the government to collect consumer records without implicating the Fourth Amendment. The doctrine strains the reasoning of all possible conceptions of the Fourth Amendment and is destined for reform. So far, scholars and jurists have advanced proposals using a cramped analytical model that attempts to balance privacy and security. They fail to account for the filterability of data. Filtering can simultaneously expand law enforcement access to relevant information while reducing access to irrelevant information. Thus, existing proposals will distort criminal justice by denying police a resource that can cabin discretion, increase distributional fairness, and exculpate the wrongly accused. This Article offers the first comprehensive analysis of third party data in police investigations by considering interests beyond privacy and security. First, it shows how existing proposals to require suspicion or a warrant will inadvertently conflict with other constitutional values, including equal protection, the First Amendment, and the due process rights of the innocent. Then it offers surgical reforms that address the most problematic applications of the doctrine: suspect-driven data collection, and bulk data collection. Well-designed reforms to the third party doctrine will shut down the data collection practices that most seriously offend civil liberties without impeding valuable, liberty-enhancing innovations in policing. -

The Book of Alternative Services of the Anglican Church of Canada with the Revised Common Lectionary

Alternative Services The Book of Alternative Services of the Anglican Church of Canada with the Revised Common Lectionary Anglican Book Centre Toronto, Canada Copyright © 1985 by the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada ABC Publishing, Anglican Book Centre General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada 80 Hayden Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4Y 3G2 [email protected] www.abcpublishing.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. Acknowledgements and copyrights appear on pages 925-928, which constitute a continuation of the copyright page. In the Proper of the Church Year (p. 262ff) the citations from the Revised Common Lectionary (Consultation on Common Texts, 1992) replace those from the Common Lectionary (1983). Fifteenth Printing with Revisions. Manufactured in Canada. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Anglican Church of Canada. The book of alternative services of the Anglican Church of Canada. Authorized by the Thirtieth Session of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada, 1983. Prepared by the Doctrine and Worship Committee of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada. ISBN 978-0-919891-27-2 1. Anglican Church of Canada - Liturgy - Texts. I. Anglican Church of Canada. General Synod. II. Anglican Church of Canada. Doctrine and Worship Committee. III. Title. BX5616. A5 1985 -

Why We Need Net Neutrality Legislation Now Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Trust the Fcc

Steffe 5.2 10/15/2010 9:43 AM WHY WE NEED NET NEUTRALITY LEGISLATION NOW OR: HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND TRUST THE FCC TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction ......................................................................................... 1150 II. The Internet Explained ...................................................................... 1152 III. Network Neutrality ............................................................................. 1154 A. What is Network Neutrality? ...................................................... 1154 B. Why Should You Care? .............................................................. 1156 IV. The Current Debate ............................................................................ 1159 V. The Comcast Crisis ............................................................................ 1162 A. Comcast Gets Caught Violating Net Neutrality ....................... 1162 B. The FCC Throws the Book at Comcast .................................... 1163 1. The Jurisdictional Battle ....................................................... 1164 2. The FCC Strikes Back—The FCC’s Approach to the Controversy ............................................................................ 1166 C. Remedies ...................................................................................... 1169 D. Comcast Cries “Foul!” ................................................................ 1169 E. The Comcast Decision’s Aftermath and the Third Way ......... 1175 VI. Post-Comcast and the Comcast Appeal ........................................... -

NYU Law Review

40216-nyu_93-2 Sheet No. 3 Side A 05/02/2018 12:38:48 \\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\93-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-MAY-18 8:21 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 93 MAY 2018 NUMBER 2 ARTICLES CONSTITUTIONAL LAW IN AN AGE OF ALTERNATIVE FACTS ALLISON ORR LARSEN* Objective facts—while perhaps always elusive—are now an endangered species. A mix of digital speed, social media, fractured news, and party polarization has led to what some call a “post-truth” society: a culture where what is true matters less than what we want to be true. At the same moment in time when “alternative facts” reign supreme, we have also anchored our constitutional law in general observations about the way the world works. Do violent video games harm child brain develop- ment? Is voter fraud widespread? Is a “partial-birth abortion” ever medically nec- essary? Judicial pronouncements on questions like these are common, and— perhaps more importantly—they are being briefed by sophisticated litigants who know how to grow the factual dimensions of their case in order to achieve the constitutional change that they want. The combination of these two forces—fact-heavy constitutional law in an environ- 40216-nyu_93-2 Sheet No. 3 Side A 05/02/2018 12:38:48 ment where facts are easy to manipulate—is cause for serious concern. This Article explores what is new and worrisome about fact-finding today, and it identifies con- stitutional disputes loaded with convenient but false claims. To remedy the problem, we must empower courts to proactively guard against alternative facts. -

Justice Scalia and Fourth Estate Skepticism Ronnell Anderson Jones S.J

SJ Quinney College of Law, University of Utah Utah Law Digital Commons Utah Law Faculty Scholarship Utah Law Scholarship 2017 Justice Scalia and Fourth Estate Skepticism RonNell Anderson Jones S.J. Quinney College of Law, University of Utah, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.law.utah.edu/scholarship Part of the First Amendment Commons, Judges Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation 15 First Amend. L. Rev. 258, 287 (2017) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Utah Law Scholarship at Utah Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Utah Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUSTICE SCALIA AND FOURTH ESTATE SKEPTICISM RonNell Andersen Jones* INTRODUCTION When news broke of the death of Justice Antonin Scalia, some aspects of the Justice's legacy were instantly apparent. It was immediately clear that he would be remembered for his advocacy of constitutional originalism, his ardent opposition to the use of legislative history in statutory interpretation, and his authorship of the watershed Second Amendment case of the modern era.1 Yet there are other, less obvious but equally significant ways that Justice Scalia made his own unique mark and left behind a Court that was fundamentally different than the one he had joined thirty years earlier. Among them is the way he impacted the relationship between the Court and the press. When Scalia was confirmed as a Justice of the U.S. -

The Gettysburg Project

The Gettysburg Project: “Of the people, by the people and for the people.” Revitalizing Public Engagement in the 21st Century CASE STUDY: What Worked in the Fight for Net Neutrality August 2015 Gettysburg Project on Civic Engagement Net Neutrality case What Worked in the Fight for Net Neutrality By Edward Walker (UCLA), Michelle Miller (Coworker.org), and Sabeel Rahman (Brooklyn Law School), with Jenny Weeks In just a few decades the Internet has evolved from a file transfer service for research institutes into a central tool for modern living. As online access becomes ever more ubiquitous in daily life, internet service providers (ISPs) – the companies that make it possible for businesses, consumers and nonprofits to get online – have become a major industry, with estimated U.S. revenues of $55 billion in 2014. The United States regulates public utilities and telecommunications providers as common carriers – businesses that offer their services to the general public at published rates. Common carriers typically are allowed to create reasonable rules to help their businesses run efficiently, but are barred from discriminating against customers without a compelling reason. Since the early 2000s regulators have struggled to determine how companies that provide broadband internet service to consumers should be regulated. Large internet service providers (ISPs) such as Comcast and Time Warner Cable have argued that treating them as common carriers would raise the cost of broadband service and stifle investment in the Internet. On the other side, free speech, civil rights and social change advocates and many companies that deliver content online argue that broadband operators should not be allowed to discriminate against types of information or classes of customers. -

KATE STITH Yale Law School, P.O

October 25, 2020 KATE STITH Yale Law School, P.O. 208215, New Haven, CT 06520-8215 Courier: 127 Wall Street, New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 432-4835 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT 1998–present: Lafayette S. Foster Professor of Law, Yale Law School Acting Dean: Spring 2009 Deputy Dean: 2003–04, 1999–2001 1991–1997: Professor of Law, Yale Law School 1985–1990: Associate Professor of Law, Yale Law School 1981–1984: Assistant United States Attorney, Southern District of New York (prosecuting white collar crime and organized crime) 1980–1981: Special Assistant to the Assistant Attorney General for the Criminal Division, Department of Justice, Washington, DC 1979–1980: Staff Economist, Council of Economic Advisers, Executive Office of the President, Washington, DC 1978–1979: Law Clerk to Justice Byron R. White, Washington, DC 1977–1978: Law Clerk to Judge Carl McGowan, United States Court of Appeals, Washington, DC LEGAL EDUCATION Harvard Law School, J.D., 1977 Articles Editor, HARVARD LAW REVIEW Harvard Prison Legal Assistance Project GRADUATE EDUCATION Harvard Kennedy School, Master in Public Policy, 1977 (joint four-year program with Harvard Law School) Master’s Thesis: THE POLITICS AND POLICY OF TAX REFORM UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION Dartmouth College, B.A., 1973 Highest Distinction in Economics Phi Beta Kappa Rank in Class: First 1 October 25, 2020 COURSES and SEMINARS Constitutional Law; Cuba and the United States; Criminal Law; Criminal Procedure: Investigations; Criminal Procedure: Adjudication; Comparative Criminal Sentencing; Criminal Sentencing; Federal Criminal Prosecution; Federal Criminal Law; Special Counsels: From Watergate to the Present; Free Exercise Clinic: Fieldwork and Seminar; Opioid Crisis; Prosecution Externship; Separation of Powers; Theories of the Fourth Amendment; University Governance; advanced seminars in criminal law and constitutional separation of powers PUBLICATIONS DEFINING FEDERAL CRIMES (Aspen Press) (1st ed. -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

The Innocents

presents THE INNOCENTS A film by Anne Fontaine 115 min | France/Poland | 2016 | PG-13 | 1.85 In French and Polish with English subtitles Official Website: http://www.musicboxfilms.com/innocents Press Materials: http://www.musicboxfilms.com/innocents-press New York/National Press Contacts: Sophie Gluck & Associates Sophie Gluck: [email protected] | 212-595-2432 Aimee Morris: [email protected] | 212-595-2432 Los Angeles Press Contacts: Marina Bailey Film Publicity Marina Bailey: [email protected] | 323-962-7511 Sara Tehrani: [email protected] | 323-962-7511 Music Box Films Contacts Marketing & Publicity Yasmine Garcia | [email protected] | 312-508-5362 Theatrical Booking Brian Andreotti | [email protected] | 312-508-5361 Exhibition Materials Lindsey Jacobs | [email protected] | 312-508-5365 FESTIVALS AND AWARDS Official Selection – Sundance Film Festival Official Selection – COLCOA Film Festival Official Selection – San Francisco Int’l Film Festival Official Selection – Minneapolis St. Paul Int’l Film Festival Official Selection – Newport Beach Film Festival SYNOPSIS Warsaw, December 1945: the second World War is finally over and French Red Cross doctor Mathilde (Lou de Laage) is treating the last of the French survivors of the German camps. When a panicked Benedictine nun appears at the clinic begging Mathilde to follow her back to the convent, what she finds there is shocking: a holy sister about to give birth and several more in advanced stages of pregnancy. A non-believer, Mathilde enters the sisters’ fiercely private world, dictated by the rituals of their order and the strict Rev. Mother (Agata Kulesza, Ida). Fearing the shame of exposure, the hostility of the occupying Soviet troops and local Polish communists and while facing an unprecedented crisis of faith, the nuns increasingly turn to Mathilde as their beliefs and traditions clash with harsh realities.