Justice Scalia and Fourth Estate Skepticism Ronnell Anderson Jones S.J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Roles of Sonia Sotomayor in Criminal Justice Cases * Christopher E

THE ROLES OF SONIA SOTOMAYOR IN CRIMINAL JUSTICE CASES * CHRISTOPHER E. SMITH AND KSENIA PETLAKH I. INTRODUCTION The unexpected death of Justice Antonin Scalia in February 20161 reminded Americans about the uncertain consequences of changes in the composition of the Supreme Court of the United States.2 It also serves as a reminder that this is an appropriate moment to assess aspects of the last major period of change for the Supreme Court when President Obama appointed, in quick succession, Justices Sonia Sotomayor in 20093 and Elena Kagan in 2010.4 Although it can be difficult to assess new justices’ decision-making trends soon after their arrival at the high court,5 they may begin to define themselves and their impact after only a few years.6 Copyright © 2017, Christopher Smith and Ksenia Petlakh. * Christopher E. Smith is a Professor of Criminal Justice, Michigan State University. A.B., Harvard University, 1980; M.Sc., University of Bristol (U.K.); J.D., University of Tennessee, 1984; Ph.D., University of Connecticut, 1988. Ksenia Petlakh is a Doctoral student in Criminal Justice, Michigan State University. B.A., University of Michigan- Dearborn, 2012. 1 Adam Liptak, Antonin Scalia, Justice on the Supreme Court, Dies at 79, N.Y. TIMES (Feb. 13, 2016), http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/14/us/antonin-scalia-death.html [https:// perma.cc/77BQ-TFEQ]. 2 Adam Liptak, Supreme Court Appointment Could Reshape American Life, N.Y. TIMES (Feb. 18, 2016), http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/19/us/politics/scalias-death-offers-best- chance-in-a-generation-to-reshape-supreme-court.html [http://perma.cc/F9QB-4UC5]; see also Edward Felsenthal, How the Court Can Reset After Scalia, TIME (Feb. -

National Press Club Luncheon with Newt Gingrich, Former Speaker of the House of Representatives

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH NEWT GINGRICH, FORMER SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES MODERATOR: JERRY ZREMSKI LOCATION: NATIONAL PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 1:00 P.M. EDT DATE: TUESDAY, AUGUST 7, 2007 (C) COPYRIGHT 2005, FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC., 1000 VERMONT AVE. NW; 5TH FLOOR; WASHINGTON, DC - 20005, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. IS A PRIVATE FIRM AND IS NOT AFFILIATED WITH THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT. NO COPYRIGHT IS CLAIMED AS TO ANY PART OF THE ORIGINAL WORK PREPARED BY A UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT OFFICER OR EMPLOYEE AS PART OF THAT PERSON'S OFFICIAL DUTIES. FOR INFORMATION ON SUBSCRIBING TO FNS, PLEASE CALL JACK GRAEME AT 202-347-1400. ------------------------- MR. ZREMSKI: (Sounds gavel.) Good afternoon, and welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Jerry Zremski, and I'm the Washington bureau chief for the Buffalo News and president of the Press Club. I'd like to welcome our club members and their guests who are with this today, as well as those of you who are watching on C-SPAN. We're looking forward to today's speech, and afterwards, I'll ask as many questions as time permits. Please hold your applause during the speech so that we have as much time for questions as possible. For our broadcast audience, I'd like to explain that if you hear applause during the speech, it may be from the guests and members of the general public who attend our luncheons and not necessarily from the working press. -

Assignment Russia’ Review: Murrow’S Man in Moscow Khrushchev Called the 6-Foot-3 Marvin Kalb ‘Peter the Great’—And in Paris Shared Croissants with the CBS Reporter

DOW JONES, A NEWS CORP COMPANY About WSJ DJIA 32627.97 0.71% ▼ S&P 500 3913.10 0.06% ▼ Nasdaq 13215.24 0.76% ▲ U.S. 10 Yr 0/32 Yield 1.726% ▼ Crude Oil 61.44 0.03% ▲ Euro 1.1906 0.09% ▼ The Wall Street Journal John Kosner GET MARKETS ALERTS English Edition Print Edition Video Podcasts Latest Headlines Home World U.S. Politics Economy Business Tech Markets Opinion Life & Arts Real Estate WSJ. Magazine Search BEST OF GUIDE TO THE OSCAR NOMINATIONS WEEKEND READS BEST BOOKS OF FEBRUARY FRESH EYES ON THE FRICK COLLECTION LATEST MOVIE REVIEWS BEST SPY NOVELS Arts & Review BEST BOOKS OF 2020 BOOKS | BOOKSHELF SHARE ‘Assignment Russia’ Review: Murrow’s Man in Moscow Khrushchev called the 6-foot-3 Marvin Kalb ‘Peter the Great’—and in Paris shared croissants with the CBS reporter. By Edward Kosner March 18, 2021 7:04 pm ET SAVE PRINT TEXT Listen to this article 6 minutes Roger Mudd ascended to Network News Heaven at 93 last week. There he was reunited with Walter Cronkite, John Chancellor, Douglas Edwards, Howard K. Smith, Edward R. Murrow and other luminaries. Still with us are old hands Dan Rather, Diane Sawyer, Bernard Shaw, and the Kalb brothers, Marvin and Bernard—living witnesses to the days when TV news was more serious business and less partisan gasbaggery. Now Marvin Kalb, himself 90 but acute as ever, has written a memoir of his early career, especially his years as Moscow correspondent for CBS News in the direst period of the Cold War. -

Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 11 Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Transatlantic Security Studies, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Kathleen Bailey presents evidence of forgeries to the press corps. Credit: The Washington Times Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference By Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 11 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2012 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

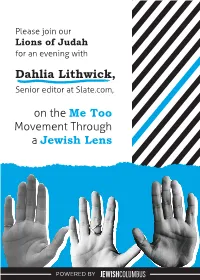

Dahlia Lithwick Invite Draft5

Please join our Lions of Judah for an evening with Dahlia Lithwick, Senior editor at Slate.com, on the Me Too Movement Through a Jewish Lens POWERED BY Dahlia Lithwick is a senior editor at Slate, and in that capacity, has been writing their “Supreme Court Dispatches” and “Jurisprudence” columns since 1999. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Harper’s, The New Yorker, The Washington Post, The New Republic, and Commentary, among other places. She is host of Amicus, Slate’s award-winning biweekly podcast about the law and the Supreme Court. She was Newsweek’s legal columnist from 2008 until 2011. Ms. Lithwick speaks frequently on the subjects of criminal justice reform, reproductive freedom, and religion in the courts. She has appeared on CNN, ABC, The Colbert Report, the Daily Show and is a frequent guest on The Rachel Maddow Show. She has testified before Congress about access to justice in the era of the Roberts Court. Ms. Lithwick earned her BA in English from Yale University and her JD degree from Stanford University. JewishColumbus’s Lion of Judah Society (LOJ) was established to provide women an opportunity to engage with their peers and increase their impact with a collective voice. Lions are women who make leadership gifts, as individuals or as part of a family gift, of $5,000 or more through JewishColumbus’s Annual Campaign. Lion of Judah dinner featuring Dahlia Lithwick, Thursday, June 4 The Terrace 711 North High Street, Columbus, OH 43215 Free valet parking Tickets: $50 each Link TBD Please RSVP by May 18 Dietary restrictions observed, catering provided by Cameron Mitchell Women’s Philanthropy Co-Chairs Jane Bodner & Emily Kandel Lion of Judah Co-Chairs Gigi Fried & Shelly Igdaloff Lion Event Co-Chairs Margie Goldach & Clemy Keidan Questions? Please contact Rachel Gleitman, Director of Women’s Philanthropy at [email protected] This event is open to Lions of Judah and Step Up Lions. -

Enrolled Original a Ceremonial Resolution 22

ENROLLED ORIGINAL A CEREMONIAL RESOLUTION 22-207 IN THE COUNCIL OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA November 7, 2017 To congratulate Meet the Press on its 70th anniversary and to recognize its longtime role as a premier political affairs television program. WHEREAS, Meet the Press is a weekly television program that offers interviews with national and global leaders, analysis of current events, and reviews of weekly news; WHEREAS, Meet the Press is the longest-running television program in television history, with the initial episode airing on November 6, 1947; WHEREAS, the radio program American Mercury Presents: Meet the Press preceded and inspired the television program; WHEREAS, in September 2015, Meet the Press debuted its daily counterpart, Meet the Press Daily; WHEREAS, in September 2016, Meet the Press launched an accompanying podcast, 1947: The Meet the Press Podcast; WHEREAS, Meet the Press regularly interviews prominent leaders and has interviewed every President of the United States since John F. Kennedy; WHEREAS, Martha Rountree served as the first moderator of Meet the Press, followed by Ned Brooks, Lawrence E. Spivak, Bill Monroe, Roger Mudd, Marvin Kalb, Chris Wallace, Garrick Utley, Tim Russert, Tom Brokaw, David Gregory, and current moderator, Chuck Todd; WHEREAS, Meet the Press has made its home in the District of Columbia, filming episodes at the NBC studio in Upper Northwest; WHEREAS, Meet the Press was the most-watched Sunday morning political affairs show for the 2016–2017 season, garnering 3.6 million viewers; and WHEREAS, Meet the Press and the American Film Institute (“AFI”) are partnering on the inaugural Meet the Press Film Festival, which celebrates both Meet the Press’ 70th 1 ENROLLED ORIGINAL anniversary and AFI’s 50th anniversary, and will feature politically focused and issue-oriented short documentaries. -

How Noninstitutionalized Media Change the Relationship Between the Public and Media Coverage of Trials

06__WHEELER__CONTRACT PROOF.DOC 11/18/2008 11:41:41 AM HOW NONINSTITUTIONALIZED MEDIA CHANGE THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE PUBLIC AND MEDIA COVERAGE OF TRIALS MARCY WHEELER* I INTRODUCTION Justice Brennan’s concurring opinion in Nebraska Press Ass’n v. Stuart1 puts citizenship and the public at the heart of the purpose of media coverage of legal proceedings: Commentary and reporting on the criminal justice system is at the core of the First Amendment values, for the operation and integrity of that system is of crucial import to citizens concerned with the administration of government. Secrecy of judicial action can only breed ignorance and distrust of courts and suspicion concerning the competence and impartiality of judges; free and robust reporting, criticism, and debate can contribute to public understanding of the rule of law and to comprehension of the functioning of the entire criminal justice system, as well as improve the quality of that system by subjecting it to the cleansing effects of exposure and public accountability.2 That is, media coverage of legal proceedings should further the public understanding of those proceedings and of the legal system generally and should foster oversight over its functioning. Unfortunately, much coverage of legal proceedings now serves to increase ratings rather than to increase the public’s understanding of the justice system.3 Moreover, examples like early coverage of the Duke lacrosse case show that the press can exacerbate—rather than expose—abuses of the judicial system and the legal system generally. Since the advent of the Internet, however, additional media outlets—like blogs and wikis—have begun to change the relationship between media Copyright © 2008 by Marcy Wheeler. -

Table of Contents

THE THEODORE H. WHITE LECTURE WITH SENATOR WARREN B. RUDMAN 1992 TABLE OF CONTENTS History of the Theodore H. White Lecture .................................................................................3 Biography of Senator Warren B. Rudman...................................................................................4 The 1992 Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics “Government in Gridlock: What Now?” by Senator Warren B. Rudman .............................................................................................5 The 1992 Theodore H. White Seminar on Press and Politics .................................................20 Senator Warren B. Rudman (R‐New Hampshire) Stephen Hess, The Brookings Institution Haynes Johnson, The Washington Post Linda Wertheimer, National Public Radio Moderated by Marvin Kalb, The Joan Shorenstein Barone Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy 2 The Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics commemorates the life of the late reporter and historian who created the style and set the standard for contemporary political journalism and campaign coverage. White, who began his journalism career delivering the Boston Post, entered Harvard College in 1932 on a newsboy’s scholarship. He studied Chinese history and Oriental languages. In 1939, he witnessed the bombing of Peking while freelance reporting on a Sheldon Fellowship, and later explained, “Three thousand human beings died; once I’d seen that I knew I wasn’t going home to be a professor.” During the war, White covered East Asia for Time and returned to write Thunder Out of China, a controversial critique of the American‐supported Nationalist Chinese government. For the next two decades, he contributed to numerous periodicals and magazines, published two books on the Second World War and even wrote fiction. A lifelong student of American political leadership, White in 1959 sought support for a 20‐year research project, a retrospective of presidential campaigns. -

NYU Law Review

40216-nyu_93-2 Sheet No. 3 Side A 05/02/2018 12:38:48 \\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\93-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-MAY-18 8:21 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 93 MAY 2018 NUMBER 2 ARTICLES CONSTITUTIONAL LAW IN AN AGE OF ALTERNATIVE FACTS ALLISON ORR LARSEN* Objective facts—while perhaps always elusive—are now an endangered species. A mix of digital speed, social media, fractured news, and party polarization has led to what some call a “post-truth” society: a culture where what is true matters less than what we want to be true. At the same moment in time when “alternative facts” reign supreme, we have also anchored our constitutional law in general observations about the way the world works. Do violent video games harm child brain develop- ment? Is voter fraud widespread? Is a “partial-birth abortion” ever medically nec- essary? Judicial pronouncements on questions like these are common, and— perhaps more importantly—they are being briefed by sophisticated litigants who know how to grow the factual dimensions of their case in order to achieve the constitutional change that they want. The combination of these two forces—fact-heavy constitutional law in an environ- 40216-nyu_93-2 Sheet No. 3 Side A 05/02/2018 12:38:48 ment where facts are easy to manipulate—is cause for serious concern. This Article explores what is new and worrisome about fact-finding today, and it identifies con- stitutional disputes loaded with convenient but false claims. To remedy the problem, we must empower courts to proactively guard against alternative facts. -

Marvin Kalb Award-Winning Reporter for CBS News and NBC News

April 2017 Marvin Kalb Award-winning Reporter for CBS News and NBC News Marvin Kalb is perhaps best known for the 30 years he spent as an award-winning reporter for CBS News and NBC News. His work at CBS landed him on Richard Nixon's "enemies list". At NBC, he served as Chief Diplomatic Correspondent and host of Meet the Press. Kalb was the founding director of the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy and Edward R. Murrow Professor of Press and Public Policy at the Kennedy School at Harvard from 1987 to 1999. He is currently a James Clark Welling Fellow at George Washington University and a member of the Atlantic Community Advisory Board. He is a guest scholar in Foreign Policy at the Brookings Institution. Subject Area/Topic: Putin’s Imperial Gamble: Ukraine and the New Cold War Highlights: He began his academic and reporting life focused on the Soviet Union. Russia and its leaders remain a preoccupation as reflected in his recent book, Imperial Gamble, Putin, Ukraine and the New Cold War. A key concept for Kalb is that democratic values, and therefore, democratic institutions are not easily implanted in East European cultures with centuries of autocratic history. He notes that “…Ukraine has always been in a dependent status”. He believes that neither the Ukrainians nor the Russians understood the terms of independence. In part, this is because those who declared independence were trained in Russia and Russian oriented. Putin has effectively been in control of Russia since 2000 and, as a result of the taking of Crimea, his popularity with the Russian people is extremely high. -

Dahlia Lithwick: American Jews' Love Affair with the Law

DAHLIA LITHWICK: AMERICAN JEWS' LOVE AFFAIR WITH THE LAW (Begin audio) Joshua Holo: Welcome to the college comments podcast, passionate perspectives, from Judaism's leading thinkers, brought to you by the Hebrew Union College, Jewish Institute of Religion, America's first Jewish institution of higher learning. My name is Joshua Holo of HUC's Jack-H Skirball campus in Los Angeles, and your host. You're listening to a special episode recorded at Symposium 2, a conference held in Los Angeles at Stephen Wise Temple in November of 2018. JH: It's my great pleasure to welcome Dahlia Lithwick to the college comments podcast. Dahlia Lithwick is a senior editor at Slate, and has been writing their Supreme Court dispatches and jurisprudence columns since 1999. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Harper's, The New Yorker, The Washington Post, The New Republic and Commentary. And she is the host of Amicus, Slate's award-winning bi-weekly podcast about the law and the Supreme Court. And I know that many of our listeners will have heard Dahlia Lithwick in some capacity or another, so it is really an honor and a pleasure to have you. Thank you for joining us. Dahlia Lithwick: It's an honor and a pleasure to be here, thank you. JH: So we're gonna start with the Jewish name game, you and I share something which is last names that no one would think are Jewish if they didn't know us. My family is Turkish, and changed its name, which in the Turkish-Jewish world is known as a Jewish name, but it was Americanized from Halio to Holo. -

The Need for a Federal Reporter Shield Law Providing Absolute Protection Against Compelled Disclosure of News Sources and Information

Trampling on the Fourth Estate: The Need for a Federal Reporter Shield Law Providing Absolute Protection Against Compelled Disclosure of News Sources and Information LESLIE SIEGEL* Disclose your sources or go to jail. That is the ultimatum being handed down with increasedand troublingfrequency by courts to journalistsacross the country. Although many states have enacted statutes that shield reporters from compelled disclosure of sources and information, those statutes offer varying degrees of protection. The result, therefore, is that whether a particularjournalist may be forced to reveal a source becomes merely an accident of geography. Adding to this air of uncertainty, the United States Supreme Court recently refused to reexamine the issue of reporterprivilege, letting stand a thirty- three-year-old decision that some lower courts interpret as allowing for a qualified reporter privilege and others read as refusing to recognize any sort ofprivilege at all. After an examination of state reportershield statutes andfederal case law, this Note concludes that the most direct and efficient way to protect journalistsfrom compelled disclosure of sources and information is through federal legislation. Although members of Congress have introduced bills providing a qualified reporterprivilege for journalists, this Note calls for the passage of a federal reporter shield law that grants an absolute privilege. This Note proposes a model statute, the Freedom of the Press Act, which would protect journalists in all media and all states against compelled disclosure of sources and information. Without an absolute federal shield in place, journalists may soon see key confidential sources dry upforfear of being unmasked; the media may self- censor to avoid facing subpoenas; reporters who decline to reveal their sources may end up behind bars; and the press may be seriously impeded in its quest to disseminatecritical information to the public.