Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on Protecting and Promoting the Open Internet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strange Bedfellows: Network Neutrality‘S Unifying Influence†

STRANGE BEDFELLOWS: NETWORK NEUTRALITY‘S UNIFYING INFLUENCE† Marvin Ammori* I want to talk about something called network (or ―net‖) neutrality. Let me begin, though, with a story involving short codes. For those unfamiliar with what a short code is, recall the voting process on American Idol and the little code that you can punch into your cell phone to vote for your favorite singer.1 Short codes are not ten digit numbers; rather, they are more like five or six.2 In theory, anyone can get a short code. Presidential candidates use short codes in their campaigns to communicate with their followers. For instance, a person could have signed up and Barack Obama would have sent them a message through a short code when he chose Joe Biden as his running mate.3 A few years ago, an abortion rights group called NARAL Pro-Choice America wanted a short code to communicate with its own followers.4 NARAL‘s goal was not to send ―spam‖; instead, the short code was directed to people who agreed with their message.5 Verizon rejected the idea of a short code for this group because, according to Verizon, NARAL was engaged in ―controversial‖ speech. The New York Times printed a front page article about this.6 Many people who read the story wondered if they really needed a permission slip from Verizon, or from anyone else, to communicate about political things that they care about. In response † This speech is adapted for publication and was originally presented at a panel discussion as part of the Regent University Law Review and The Federalist Society for Law & Public Policy Studies Media and Law Symposium at Regent University School of Law, October 9–10, 2009. -

Why We Need Net Neutrality Legislation Now Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Trust the Fcc

Steffe 5.2 10/15/2010 9:43 AM WHY WE NEED NET NEUTRALITY LEGISLATION NOW OR: HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND TRUST THE FCC TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction ......................................................................................... 1150 II. The Internet Explained ...................................................................... 1152 III. Network Neutrality ............................................................................. 1154 A. What is Network Neutrality? ...................................................... 1154 B. Why Should You Care? .............................................................. 1156 IV. The Current Debate ............................................................................ 1159 V. The Comcast Crisis ............................................................................ 1162 A. Comcast Gets Caught Violating Net Neutrality ....................... 1162 B. The FCC Throws the Book at Comcast .................................... 1163 1. The Jurisdictional Battle ....................................................... 1164 2. The FCC Strikes Back—The FCC’s Approach to the Controversy ............................................................................ 1166 C. Remedies ...................................................................................... 1169 D. Comcast Cries “Foul!” ................................................................ 1169 E. The Comcast Decision’s Aftermath and the Third Way ......... 1175 VI. Post-Comcast and the Comcast Appeal ........................................... -

The Gettysburg Project

The Gettysburg Project: “Of the people, by the people and for the people.” Revitalizing Public Engagement in the 21st Century CASE STUDY: What Worked in the Fight for Net Neutrality August 2015 Gettysburg Project on Civic Engagement Net Neutrality case What Worked in the Fight for Net Neutrality By Edward Walker (UCLA), Michelle Miller (Coworker.org), and Sabeel Rahman (Brooklyn Law School), with Jenny Weeks In just a few decades the Internet has evolved from a file transfer service for research institutes into a central tool for modern living. As online access becomes ever more ubiquitous in daily life, internet service providers (ISPs) – the companies that make it possible for businesses, consumers and nonprofits to get online – have become a major industry, with estimated U.S. revenues of $55 billion in 2014. The United States regulates public utilities and telecommunications providers as common carriers – businesses that offer their services to the general public at published rates. Common carriers typically are allowed to create reasonable rules to help their businesses run efficiently, but are barred from discriminating against customers without a compelling reason. Since the early 2000s regulators have struggled to determine how companies that provide broadband internet service to consumers should be regulated. Large internet service providers (ISPs) such as Comcast and Time Warner Cable have argued that treating them as common carriers would raise the cost of broadband service and stifle investment in the Internet. On the other side, free speech, civil rights and social change advocates and many companies that deliver content online argue that broadband operators should not be allowed to discriminate against types of information or classes of customers. -

Network Neutrality in the United States and How the Current Economic Environment Presents a Unique Opportunity to Invest in the Future of the Internet Andrew Seitz

Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary Volume 29 | Issue 2 Article 8 10-15-2009 It's a Series of Tubes: Network Neutrality in the United States and How the Current Economic Environment Presents a Unique Opportunity to Invest in the Future of the Internet Andrew Seitz Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/naalj Part of the Communications Law Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew Seitz, It's a Series of Tubes: Network Neutrality in the United States and How the Current Economic Environment Presents a Unique Opportunity to Invest in the Future of the Internet , 29 J. Nat’l Ass’n Admin. L. Judiciary Iss. 2 (2009) Available at: http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/naalj/vol29/iss2/8 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. It's a Series of Tubes: Network Neutrality in the United States and How the Current Economic Environment Presents a Unique Opportunity to Invest in the Future of the Internet By Andrew Seitz* Table of Contents 1. IN TRO D UCTIO N .......................................................................................................................... 684 A. What is Network Neutrality? .......................................................................................... -

It's a Series of Tubes: Network Neutrality in the United States And

Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary Volume 29 Issue 2 Article 8 10-15-2009 It's a Series of Tubes: Network Neutrality in the United States and How the Current Economic Environment Presents a Unique Opportunity to Invest in the Future of the Internet Andrew Seitz Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/naalj Part of the Communications Law Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew Seitz, It's a Series of Tubes: Network Neutrality in the United States and How the Current Economic Environment Presents a Unique Opportunity to Invest in the Future of the Internet , 29 J. Nat’l Ass’n Admin. L. Judiciary Iss. 2 (2009) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/naalj/vol29/iss2/8 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. It's a Series of Tubes: Network Neutrality in the United States and How the Current Economic Environment Presents a Unique Opportunity to Invest in the Future of the Internet By Andrew Seitz* Table of Contents 1. IN TRO D UCTIO N .......................................................................................................................... 684 A. What is Network Neutrality? ........................................................................................... 685 1. Absolute View of Network Neutrality ................................................................... 687 2. Narrow View of Network Neutrality ..................................................................... 687 B . The P lay ers ...................................................................................................................... 690 1. -

The Next Big Battle in Internet Policy by Marvin Ammori | Posted Tuesday, Oct

http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2012/10/network_neutrality_the_fcc_and_the_internet_of_things_.html The Next Big Battle in Internet Policy By Marvin Ammori | Posted Tuesday, Oct. 2, 2012, at 11:26 AM ET | Posted Tuesday, Oct. 2, 2012, at 11:26 AM ET Slate.com The Next Big Battle in Internet Policy When your smartphone can talk to your fridge, network neutrality will be more important than ever. For two years, network neutrality, the nation’s most high-profile and contentious Internet policy conflict has taken a backseat to other debates—privacy investigations by the Federal Trade Commission, cybersecurity orders from the White House, proposed copyright legislation like SOPA and PIPA, software patents in courts, and censorship abroad. After nearly a decade of (rarely productive) debate, net neutrality—restrictions on Internet service providers to ensure consumers experience freedom online—has rarely been in the news since early 2011. Former Alaska Sen. Ted Stevens famously observed the the Internet is a "series of tubes" Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images. But that quiet won’t last much longer. We have merely been in an extended intermission, and soon we will watch the third act in this play unfold. At stake is access to the mobile Internet on the handhelds and tablets in our pockets—as well as access by the chips increasingly embedded in our clothes, toasters, and heart monitors. Act I: Dial-up, from Internet’s birth to circa 2005 Network neutrality is a proposed legal principle that would prohibit Internet service providers from blocking or slowing down access to certain websites and online software. -

Intertubes: a Study of the US Long-Haul Fiber-Optic Infrastructure

InterTubes: A Study of the US Long-haul Fiber-optic Infrastructure Ramakrishnan Durairajan†, Paul Barford†*, Joel Sommers+, Walter Willinger‡ {rkrish,pb}@cs.wisc.edu, [email protected], [email protected] †University of Wisconsin - Madison *comScore, Inc. +Colgate University ‡NIKSUN, Inc. ABSTRACT 1 Introduction The complexity and enormous costs of installing new long- The desire to tackle the many challenges posed by novel haul fiber-optic infrastructure has led to a significant amount designs, technologies and applications such as data cen- of infrastructure sharing in previously installed conduits. In ters, cloud services, software-defined networking (SDN), this paper, we study the characteristics and implications of network functions virtualization (NFV), mobile communi- infrastructure sharing by analyzing the long-haul fiber-optic cation and the Internet-of-Things (IoT) has fueled many of network in the US. the recent research efforts in networking. The excitement We start by using fiber maps provided by tier-1 ISPs and surrounding the future envisioned by such new architectural major cable providers to construct a map of the long-haul US designs, services, and applications is understandable, both fiber-optic infrastructure. We also rely on previously under- from a research and industry perspective. At the same time, utilized data sources in the form of public records from fed- it is either taken for granted or implicitly assumed that the eral, state, and municipal agencies to improve the fidelity physical infrastructure of tomorrow’s Internet will have the of our map. We quantify the resulting map’s1 connectivity capacity, performance, and resilience required to develop characteristics and confirm a clear correspondence between and support ever more bandwidth-hungry, delay-intolerant, long-haul fiber-optic, roadway, and railway infrastructures. -

The Network Neutrality Debate How Irrelevant Arguments Can Decide the Outcome of a Controversy Over Technology

Zane Van Dusen The Network Neutrality Debate How Irrelevant Arguments Can Decide the Outcome of a Controversy over Technology The situation seemed pretty bad for network neutrality proponents in the early months of 2006. The telecom companies were confidently planning bills that allowed for a multi-tiered internet, while some news articles said that “it may be too late” to defeat or even hinder the bill.1 However, for most part, people were unaware of the situation. Even in May 2006, lobbyists were saying that the telecom companies’ bill “caught a lot of people off guard.”2 However, a group of grass roots organizations was somehow able to change all of this in a matter of a several months, and create a massive public backlash against the bill. What makes this feat even more impressive is that the organizations were able to generate so much support, despite the fact that network neutrality is such a complex and technical issue. Although network neutrality proponents had a solid argument supported by reliable studies, this was not enough to interest the general public in the debate over network neutrality. Instead, they had to resort to a campaign based on deceptive language, entertaining videos, and anti-corporate propaganda. The surprising effectiveness of this grass roots campaign led the telecom companies to start their own campaign. This campaign was very similar to that of the network neutrality proponents; they created “grass roots” organizations, and produced propaganda that attacked the large corporations who supported network neutrality. Even U.S. senators, like Ted Stevens, got involved in the rhetoric, by speaking out against network neutrality using misleading metaphors and irrelevant information. -

The Next Generation of the Internet Revolutionizing the Way We Work, Live, Play, and Learn

Point of View The Next Generation of the Internet Revolutionizing the Way We Work, Live, Play, and Learn Author Stuart Taylor April 2013 Cisco Internet Business Solutions Group (IBSG) Cisco IBSG © 2013 Cisco and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. 04/13 Point of View The Next Generation of the Internet Revolutionizing the Way We Work, Live, Play, and Learn Former U.S. Senator Ted Stevens (Alaska) provided comedians plenty of fodder when, in 2006, he described the Internet as a “series of tubes.” But, that’s what it is.1 There are tubes under the ocean, connecting the world’s financial centers of London and New York. There are tubes that connect Google to Facebook. There are buildings filled with tubes that con- nect data centers and virtual private networks. There are hundreds of miles of tubes buried beside roads and railroad tracks. And, this network of tubes is expanding at a phenomenal rate, connecting most parts of the world. In fact, there are close to 1.5 million kilometers (920,000 miles) of fiber-optic cables spanning the world’s oceans and circling the globe.2 Marshall McLuhan, a Canadian philosopher of communication theory, could never have imagined the power of the interconnected, global network that exists today when he coined the famous term “Global Village.” “The new electronic interdependence re-creates the world in the image of a global village.” Marshall McLuhan Philosopher of Communication Theory No one could have imagined the fundamental impact the Internet would have on both soci- ety and the economy—changing our lives forever. -

The Internet Is a Series of Tubes Henning Schulzrinne, Columbia University Availability, Affordability and Relevance

The Internet is a Series of Tubes Henning Schulzrinne, Columbia University Availability, Affordability and Relevance Internet adoption tends to progress in phases: early rapid adoption in urban areas and by relatively well-educated and higher-income households, then transitioning to a slower pace once between 70 and 85% of households subscribe. For example, in a 2013 survey, the Pew Research Internet Project found that approximately 15% of the adult population does not use the Internet; those least likely to use the Internet include “senior citizens, adults with less than a high-school education and those living in households earning less than $30,000 per year.”1 1 http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/broadband-technology-fact-sheet/ NTIA 2014 Non-adoption has multiple reasons that vary in each country, and, within each country, by demographics. These reasons are often grouped, somewhat crudely, as availability, affordability and relevance. For the United States, a 2014 NTIA survey identified 48% as stating “Don’t need. Not interested.”, often summarized as “relevance”, as the main reason for not using the Internet at home, followed by “too expensive” (29%), “no computer or computer inadequate” (11%). Only 1% each claimed that there was no Internet access available or that privacy or security concerns dominated. A small percentage (3%) use the Internet somewhere else, e.g., at work, in coffee shops or a library. It is likely that many individuals will have multiple reasons and some non-users increasingly use functions on smartphones that may require Internet access, e.g., for maps or games, that may not be appear to the user as such. -

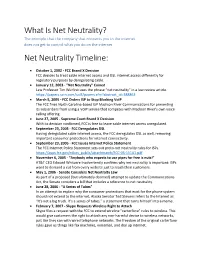

Net Neutrality Timeline

What Is Net Neutrality? The principle that the company that connects you to the internet does not get to control what you do on the internet. Net Neutrality Timeline: • October 1, 2002 - FCC Brand X Decision FCC decides to treat cable internet access and DSL internet access differently for regulatory purposes by deregulating cable. • January 12, 2003 - “Net Neutrality” Coined Law Professor Tim Wu first uses the phrase “net neutrality” in a law review article. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=388863 • March 5, 2005 - FCC Orders ISP to Stop Blocking VoIP The FCC fines North Carolina-based ISP Madison River Communications for preventing its subscribers from using a VoIP service that competes with Madison River's own voice calling offering. • June 27, 2005 - Supreme Court Brand X Decision With its decision confirmed, FCC is free to leave cable internet access unregulated. • September 23, 2005 - FCC Deregulates DSL Having deregulated cable internet access, the FCC deregulates DSL as well, removing important consumer protections for internet connectivity. • September 23, 2005 - FCC Issues Internet Policy Statement The FCC Internet Policy Statement sets out proto-net neutrality rules for ISPs. https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/FCC-05-151A1.pdf • November 6, 2005 - “Anybody who expects to use pipes for free is nuts!” AT&T CEO Edward Whitacre inadvertently confirms why net neutrality is important: ISPs want to demand a cut from every website just to reach their customers. • May 1, 2006 - Senate Considers Net Neutralty Law As part of a proposed (but ultimately doomed) attempt to update the Communications Act, the Senate considers a bill that includes a reference to net neutrality. -

Fourth Amendment “Papers” and the Third-Party Doctrine

Cite as Michael W. Price, 8 J. NAT’L SECURITY L. & POL’Y ___ (forthcoming 2015) RETHINKING PRIVACY: FOURTH AMENDMENT “PAPERS” AND THE THIRD-PARTY DOCTRINE Michael W. Price* INTRODUCTION Most Americans now live in a world where nearly every call or click online leaves a digital trail that can be stored, searched, and stitched together to reveal an intimate portrait of private life. But current law affords little privacy protection to information about these activities, undermining First and Fourth Amendment safeguards that are essential to individual freedoms and a robust democracy. The so-called third-party doctrine1 has created a privacy gap by denying Fourth Amendment protection to expressive and associational data processed by third parties, including communications information and data stored in the “cloud.” Exacerbated by rapid advances in information technology and a proliferation of third-party records, the gulf continues to widen. Congress has not stepped in to fill the void. The laws that govern online privacy are older than the World Wide Web.2 It is a frequent and wholly justified criticism of the American legal system that a great number of the people in charge of making the rules for modern information technology have little or no experience using email, sending a text, or reading a blog.3 And federal courts have been reluctant to delve into the business of * Counsel, Liberty & National Security Program, Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law. 1 See United States v. Miller, 425 U.S. 435 (1976); Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735 (1979). 2 Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986, Pub.