Conservation Research 1996/1997

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamically Tunable Plasmonic Structural Color

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Dynamically Tunable Plasmonic Structural Color Daniel Franklin University of Central Florida Part of the Physics Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Franklin, Daniel, "Dynamically Tunable Plasmonic Structural Color" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5880. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5880 DYNAMICALLY TUNABLE PLASMONIC STRUCTURAL COLOR by DANIEL FRANKLIN B.S. Missouri University of Science and Technology, 2011 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Physics in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Debashis Chanda © 2018 Daniel Franklin ii ABSTRACT Functional surfaces which can control light across the electromagnetic spectrum are highly desirable. With the aid of advanced modeling and fabrication techniques, researchers have demonstrated surfaces with near arbitrary tailoring of reflected/transmitted amplitude, phase and polarization - the applications for which are diverse as light itself. These systems often comprise of structured metals and dielectrics that, when combined, manifest resonances dependent on structural dimensions. This attribute provides a convenient and direct path to arbitrarily engineer the surface’s optical characteristics across many electromagnetic regimes. -

Comparative Visualization for Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography

COMPARATIVE VISUALIZATION FOR TWO-DIMENSIONAL GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY by Ben Hollingsworth A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Computer Science Under the Supervision of Professor Stephen E. Reichenbach Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2004 COMPARATIVE VISUALIZATION FOR TWO-DIMENSIONAL GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY Ben Hollingsworth, M.S. University of Nebraska, 2004 Advisor: Stephen E. Reichenbach This work investigates methods for comparing two datasets from comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography (GC×GC). Because GC×GC introduces incon- sistencies in feature locations and pixel magnitudes from one dataset to the next, several techniques have been developed for registering two datasets to each other and normalizing their pixel values prior to the comparison process. Several new methods of image comparison improve upon pre-existing generic methods by taking advantage of the image characteristics specific to GC×GC data. A newly developed colorization scheme for difference images increases the amount of information that can be pre- sented in the image, and a new “fuzzy difference” algorithm highlights the interesting differences between two scalar rasters while compensating for slight misalignment between features common to both images. In addition to comparison methods based on two-dimensional images, an inter- active three-dimensional viewing environment allows analysts to visualize data using multiple comparison methods simultaneously. Also, high-level features extracted from the images may be compared in a tabular format, side by side with graphical repre- sentations overlaid on the image-based comparison methods. These image processing techniques and high-level features significantly improve an analyst’s ability to detect similarities and differences between two datasets. -

The Collaboration of Niccolò Tegliacci and Luca Di Tommè

The Collaboration of Niccolô Tegliacci and Lúea di Tomme This page intentionally left blank J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM Publication No. 5 THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLÔ TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ BY SHERWOOD A. FEHM, JR. !973 Printed by Anderson, Ritchie & Simon Los Angeles, California THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLO TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ The economic and religious revivals which occurred in various parts of Italy during the late Middle Ages brought with them a surge of .church building and decoration. Unlike the typically collective and frequently anonymous productions of the chan- tiers and ateliers north of the Alps which were often passed over by contemporary chroniclers of the period, artistic creativity in Italy during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries documents the emergence of distinct "schools" and personalities. Nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than in Tuscany where indi- vidual artists achieved sufficient notoriety to appear in the writ- ings of their contemporaries. For example, Dante refers to the fame of the Florentine artist Giotto, and Petrarch speaks warmly of his Sienese painter friend Simone Martini. Information regarding specific artists is, however, often l^ck- ing or fragmentary. Our principal source for this period, The Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects by Giorgio Vasari, was written more than two hundred years after Giotto's death. It provides something of what is now regarded as established fact often interspersed with folk tales and rumor. In spite of the enormous losses over the centuries, a large num- ber of paintings survived from the Dugento and Trecento. Many of these are from Central Italy, and a relatively small number ac- tually bear the signature of the artist who painted them. -

Das Internet Und Die Leugnung Des Holocaust

Bei dieser Arbeit handelt es sich um eine Wissenschaftliche Hausarbeit, die an der Universität Kassel angefertigt wurde. Die hier veröffentlichte Version kann von der als Prüfungsleistung eingereichten Version geringfügig abweichen. Weitere Wissenschaftliche Hausarbeiten finden Sie hier: https://kobra.bibliothek.uni-kassel.de/handle/urn:nbn:de:hebis:34-2011040837235 Diese Arbeit wurde mit organisatorischer Unterstützung des Zentrums für Lehrerbildung der Universität Kassel veröffentlicht. Informationen zum ZLB finden Sie unter folgendem Link: www.uni-kassel.de/zlb Wissenschaftliche Hausarbeit im Rahmen der Ersten Staatsprüfung für das Lehramt an Gymnasien im Fach Geschichte Eingereicht dem Amt für Lehrerbildung Prüfungsstelle Kassel Thema: „Das Internet und die Leugnung des Holocaust. Neue Perspektiven in deutschsprachigen Veröffentlichungen“ Vorgelegt von: Dennis Beismann 2011 Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Friedhelm Boll Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung............................................................................................................1 1.1 Stand der Forschung.....................................................................................3 1.1.1 Publikationen aus den Jahren 1970 bis 1993........................................3 1.1.2 Holocaustleugnende Publikationen im Internet....................................4 1.2 Anlage der Studie.........................................................................................7 1.2.1 Fragestellung.........................................................................................7 -

HD Tv-Reclame in België D-MAT HD

HD Tv-reclame in België D-MAT HD Audio-, video- en taalformaten naargelang de regie en zender : Steeds één enkele spot per D-MAT HD bestand! één enkele bestand per regie, per taal, per formaat ! IP : RTL-TVI , PLUG RTL , CLUB RTL , TF1, MY TF1, RTL PLAY, 6PLAY : 1 D-MAT HD bestand (FR) RMB : RTBF La Une , RTBF TIPIK , RTBF La Trois , RTBF AUVIO, AB3 , ABXPLORE, LN24, BeTV, NRJ HITS : 1 D-MAT HD bestand (FR) VAR : VRT EEN, CANVAS, SPORZA, KETNET, VRT NU : 1 D-MAT HD bestand (NL) SBS : VIER, VIJF, ZES, TLC, DISCOVERY, NJAM!, TLC, PLAY SPORTS, NRJ, NATIVE NATION, JANI : 1 D-MAT HD bestand (NL) IP BELGIUM C/O RMB RMB 2, BVD LOUIS SCHMIDTLAAN VAR B - 1040 BRUXELLES – BRUSSEL DPG MEDIA TEL. +32-2-730 44 11 – FAX +32-2-726 64 25 – ING 310-0613250-05 SBS BELGIUM EMAIL : [email protected] DPG MEDIA : vtm, vtm2, vtm3, vtm4, CAZ2, vtmKIDS, vtmGO, vtmKOKEN : 1 D-MAT HD bestand (NL) TRANSFER : VICE TV – SPIKE – MTV – NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC – HISTORY – FOX - CARTOON NETWORK – ECLIPS TV - XITE – DOBBIT TV – STUDIO100 TV – COMEDY CENTRAL - MENT TV – KANAAL Z - PLATTELANDS TV – ELEVEN : 1 D-MAT HD bestand (NL) BX1 – CANAL Z – 13ieme RUE – CARTOON NETWORK – DOBBIT TV – NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC – MTV – STUDIO 100 TV – VICE TV – C8 – ELEVEN : 1 D-MAT HD bestand (FR) RESEAU DES MEDIAS DE PROXIMITE: ANTENNE CENTRE TELEVISION – CANAL C – CANALZOOM – MATELE – NOTELE – RTC – TELE MB – TELE SAMBRE – TVCOM – TV LUX - VEDIA : 1 D-MAT HD bestand (FR) BRIGHTFISH : meer dan 400 bioscoop zalen in België 1 D-MAT HD bestand (NL) 1 D-MAT HD bestand (FR) IP BELGIUM C/O RMB RMB 2, BVD LOUIS SCHMIDTLAAN VAR B - 1040 BRUXELLES – BRUSSEL DPG MEDIA TEL. -

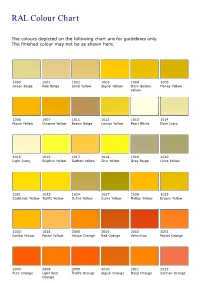

RAL Colour Chart

RAL Colour Chart The colours depicted on the following chart are for guidelines only. The finished colour may not be as shown here. 1000 1001 1002 1003 1004 1005 Green Beige Pale Beige Sand Yellow Signal Yellow Dark Golden Honey Yellow Yellow 1006 1007 1011 1012 1013 1014 Maize Yellow Chrome Yellow Brown Beige Lemon Yellow Pearl White Dark Ivory 1015 1016 1017 1018 1019 1020 Light Ivory Sulphur Yellow Saffron Yellow Zinc Yellow Grey Beige Olive Yellow 1021 1023 1024 1027 1028 1032 Cadmium Yellow Traffic Yellow Ochre Yellow Curry Yellow Mellon Yellow Broom Yellow 1033 1034 2000 2001 2002 2003 Dahlia Yellow Pastel Yellow Yellow Orange Red Orange Vermillion Pastel Orange 2004 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Pure Orange Light Red Traffic Orange Signal Orange Deep Orange Salmon Orange Orange 3000 3001 3002 3003 3004 3005 Flame Red RAL Signal Red Carmine Red Ruby Red Purple Red Wine Red 3007 3009 3011 3012 3013 3014 Black Red Oxide Red Brown Red Beige Red Tomato Red Antique Pink 3015 3016 3017 3018 3020 3022 Light Pink Coral Red Rose Strawberry Red Traffic Red Dark Salmon Red 3027 3031 4001 4002 4003 4004 Raspberry Red Orient Red Red Lilac Red Violet Heather Violet Claret Violet 4005 4006 4007 4008 4009 4010 Blue Lilac Traffic Purple Purple Violet Signal Violet Pastel Violet Telemagenta 5000 5001 5002 5003 5004 5005 Violet Blue Green Blue Ultramarine Blue dark Sapphire Black Blue Signal Blue Blue 5007 5008 5009 5010 5011 5012 Brilliant Blue Grey Blue Light Azure Blue Gentian Blue Steel Blue Light Blue 5013 5014 5015 5017 5018 5019 Dark Cobalt Blue -

015-019 Dossier AB3-5P 6/04/06 18:14 Page 15

015-019 Dossier AB3-5p 6/04/06 18:14 Page 15 dossier dossier AB3 ou le cheval de trop Théo Hachez AB3 ou le cheval de trop Assez tranquille au cours des années nonante, le paysage télévisuel de la Communauté française aura été dérangé, en ce début de millénaire, par l’apparition d’AB3. Les deux canaux des deux opérateurs principaux (La Une et La Deux de la R.T.B.F. et, pour R.T.L./T.V.I., Club R.T.L. et sa chaine éponyme) devront désormais compter avec une chaine gratuite à vocation généraliste de plus et, quelques mois plus tard, avec sa jumelle AB4. L’insignifiance culturelle et l’audience modeste recueillie par les nouvelles venues donnent une faible idée de la menace que leur vraie raison d’être fait peser à terme sur l’assise financière des médias de la Communauté française… Théo Hachez Il faut le dire: personne n’avait vu venir ment fleuri, mais le marché francophone le danger tel qu’il se dessine aujourd’hui. apparaissait trop mince et déjà trop Ni les ministres successifs saisis d’un encombré pour assurer sa viabilité. Au- dossier de reconnaissance au nom de trement dit, même sans pouvoir s’impo- Y.T.V., ni le Conseil supérieur de l’audio- ser comme un concurrent à part entière, visuel (C.S.A.) chargé de l’analyser. Seule Y.T.V. serait de toute façon plus ou moins R.T.L./T.V.I., sur les terres de laquelle un durablement nuisible aux intérêts de projet de télévision généraliste plus ciblé R.T.L./T.V.I. -

Watercolours: What´S Different in the New Assortment?

Product information Watercolours HORADAM® watercolours: What´s different in the new assortment? The following colours have got a new name: Art.-No. Old Name New Name 14 208 Aureolin modern Aureolin hue 14 209 Translucent yellow Transparent Yellow 14 211 Chrome yellow lemon Chromium yellow hue lemon 14 212 Chrome yellow light Chromium yellow hue light 14 213 Chrome yellow deep Chromium yellow hue deep 14 214 Chrome orange Chromium orange hue 14 218 Translucent orange Transparent orange 14 366 Deep red Perylene maroon 14 476 Mauve Schmincke violet 14 498 Dark blue indigo Dark blue 14 648 Sepia brown tone Sepia brown reddish 14 786 Charcoal grey Anthracite The following colours are completely omitted due to raw materials which aren’t available anymore: Art.-No. Old Name 14 652 Walnut brown This tone cannot be mixed out of other colours. 14 666 Pozzuoli earth This tone can be mixed using 14 649 English Venetian red and the slightly reddish 14 670 Madder brown. These colours are now produced using other pigments. Therefore they have got a new name and a new number: Old Art.-No. Old Name New Art.-No. New Name 14 345 Dark red 14 344 Perylene dark red 14 210 Gamboge gum modern 14 217 Quinacridone gold hue 14 478 Helio blue reddish 14 477 Phthalo sapphire blue 14 536 Green yellow 14 537 Transparent green gold - Discontinued colours The described product attributes and application examples have been tes- a warranty for product attributes and/or assume liability for damages that ted in the Schmincke laboratory. -

A Closer Look at Santos

A Closer Look at Santos Objects tell us about ourselves. As we look at their style and symbolism, we can tell a great deal about the artists who made them and about the societies in which artists lived and worked. When we extend our observations by means of techniques that "see" more than the naked eye, we also expand what we can learn. Creative processes - the materials and techniques that artists chose, cultural and traditional influences - become apparent, along with physical evidence of an object's particular history. What has happened to an object may tell us about shifts in its place in society and thus about a society itself. In A Closer Look at Santos, we address other ways of looking at santos, intended for anyone interested in a long and still lively cultural tradition. Santos have been made for centuries, since the early Spanish Colonial era. In the Americas, three main traditions of artisanship - Flemish, Italian, and Spanish - contributed to a distinctly New World style, which blended local expressions and native materials with older imported styles. Today, dedicated artists in Hispanic-American communities are still creating santos, working within an evolving tradition steeped in a rich history but adapting to modern society. Santos, as objects of veneration that play an important role in religious life, lie at the very heart of the Latino cultural tradition. Specialized scientific techniques offer new ways to appreciate them and thus to celebrate some of the many threads that weave the tapestry of contemporary American culture. Seeing with Scientific Techniques In examining santos, archives of historical and anthropological literature are important sources, as are comparative studies of imagery - iconography and iconology. -

Utopian Reality Russian History and Culture

Utopian Reality Russian History and Culture Editors-in-Chief Jeffrey P. Brooks The Johns Hopkins University Christina Lodder University of Kent VOLUME 14 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/rhc Utopian Reality Reconstructing Culture in Revolutionary Russia and Beyond Edited by Christina Lodder Maria Kokkori and Maria Mileeva LEIDEn • BOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Staircase in the residential building for members of the Cheka (the Secret Police), Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg), 1929–1936, designed by Ivan Antonov, Veniamin Sokolov and Arsenii Tumbasov. Photograph Richard Pare. © Richard Pare. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Utopian reality : reconstructing culture in revolutionary Russia and beyond / edited by Christina Lodder, Maria Kokkori and Maria Mileeva. pages cm. — (Russian history and culture, ISSN 1877-7791; volume 14) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-26320-8 (hardback : acid-free paper)—ISBN 978-90-04-26322-2 (e-book) 1. Soviet Union—Intellectual life—1917–1970. 2. Utopias—Soviet Union—History. 3. Utopias in literature. 4. Utopias in art. 5. Arts, Soviet—History. 6. Avant-garde (Aesthetics)—Soviet Union—History. 7. Cultural pluralism—Soviet Union—History. 8. Visual communication— Soviet Union—History. 9. Politics and culture—Soviet Union—History 10. Soviet Union— Politics and government—1917–1936. I. Lodder, Christina, 1948– II. Kokkori, Maria. III. Mileeva, Maria. DK266.4.U86 2013 947.084–dc23 2013034913 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. -

Read Book Kazimir Malevich

KAZIMIR MALEVICH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Achim Borchardt-Hume | 264 pages | 21 Apr 2015 | TATE PUBLISHING | 9781849761468 | English | London, United Kingdom Kazimir Malevich PDF Book From the beginning of the s, modern art was falling out of favor with the new government of Joseph Stalin. Red Cavalry Riding. Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. The movement did have a handful of supporters amongst the Russian avant garde but it was dwarfed by its sibling constructivism whose manifesto harmonized better with the ideological sentiments of the revolutionary communist government during the early days of Soviet Union. What's more, as the writers and abstract pundits were occupied with what constituted writing, Malevich came to be interested by the quest for workmanship's barest basics. Black Square. Woman Torso. The painting's quality has degraded considerably since it was drawn. Guggenheim —an early and passionate collector of the Russian avant-garde—was inspired by the same aesthetic ideals and spiritual quest that exemplified Malevich's art. Hidden categories: Articles with short description Short description matches Wikidata Use dmy dates from May All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from June Lyubov Popova - You might like Left Right. Harvard doctoral candidate Julia Bekman Chadaga writes: "In his later writings, Malevich defined the 'additional element' as the quality of any new visual environment bringing about a change in perception Retrieved 6 July A white cube decorated with a black square was placed on his tomb. It was one of the most radical improvements in dynamic workmanship. Landscape with a White House. -

U.S. Government Printing Office Style Manual, 2008

U.S. Government Printing Offi ce Style Manual An official guide to the form and style of Federal Government printing 2008 PPreliminary-CD.inddreliminary-CD.indd i 33/4/09/4/09 110:18:040:18:04 AAMM Production and Distribution Notes Th is publication was typeset electronically using Helvetica and Minion Pro typefaces. It was printed using vegetable oil-based ink on recycled paper containing 30% post consumer waste. Th e GPO Style Manual will be distributed to libraries in the Federal Depository Library Program. To fi nd a depository library near you, please go to the Federal depository library directory at http://catalog.gpo.gov/fdlpdir/public.jsp. Th e electronic text of this publication is available for public use free of charge at http://www.gpoaccess.gov/stylemanual/index.html. Use of ISBN Prefi x Th is is the offi cial U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identifi ed to certify its authenticity. ISBN 978–0–16–081813–4 is for U.S. Government Printing Offi ce offi cial editions only. Th e Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Offi ce requests that any re- printed edition be labeled clearly as a copy of the authentic work, and that a new ISBN be assigned. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 978-0-16-081813-4 (CD) II PPreliminary-CD.inddreliminary-CD.indd iiii 33/4/09/4/09 110:18:050:18:05 AAMM THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE STYLE MANUAL IS PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION AND AUTHORITY OF THE PUBLIC PRINTER OF THE UNITED STATES Robert C.