Comparative Visualization for Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamically Tunable Plasmonic Structural Color

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Dynamically Tunable Plasmonic Structural Color Daniel Franklin University of Central Florida Part of the Physics Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Franklin, Daniel, "Dynamically Tunable Plasmonic Structural Color" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5880. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5880 DYNAMICALLY TUNABLE PLASMONIC STRUCTURAL COLOR by DANIEL FRANKLIN B.S. Missouri University of Science and Technology, 2011 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Physics in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Debashis Chanda © 2018 Daniel Franklin ii ABSTRACT Functional surfaces which can control light across the electromagnetic spectrum are highly desirable. With the aid of advanced modeling and fabrication techniques, researchers have demonstrated surfaces with near arbitrary tailoring of reflected/transmitted amplitude, phase and polarization - the applications for which are diverse as light itself. These systems often comprise of structured metals and dielectrics that, when combined, manifest resonances dependent on structural dimensions. This attribute provides a convenient and direct path to arbitrarily engineer the surface’s optical characteristics across many electromagnetic regimes. -

Painted Wood: History and Conservation

PART FOUR Investigations and Treatment 278 Monochromy, Polychromy, and Authenticity The Cloisters’ Standing Bishop Attributed to Tilman Riemenschneider Michele D. Marincola and Jack Soultanian 1975, Standing Bishop was acquired for The Cloisters collection, the Metropolitan Museum of IArt, New York. This piece—considered at purchase to be a mature work of Tilman Riemenschneider (ca. 1460–1531), a leading German mas- ter of Late Gothic sculpture—was intended to complement early works by the artist already in the collection. The sculpture (Fig. 1) is indisputably in the style of Riemenschneider; furthermore, its provenance (established to before 1907) includes the renowned Munich collection of Julius Böhler.1 The Standing Bishop was accepted as an autograph work by the great Riemenschneider scholar Justus Bier (1956), who was reversing his earlier opinion. It has been compared stylistically to a number of works by Riemenschneider from about 1505–10. In the 1970s, a research project was begun by art historians and conservators in Germany to establish the chronology and authorship of a group of sculptures thought to be early works of Riemenschneider. The Cloisters’ sculptures, including the Standing Bishop, were examined as part of the project, and cross sections were sent to Munich for analysis by Hermann Kühn. This research project resulted in an exhibition of the early work of Riemenschneider in Würzburg in 1981; The Cloisters sent two sculptures from its collection, but the loan of the Standing Bishop was not requested. Certain stylistic anomalies of the figure, as well as several Figure 1 technical peculiarities discussed below, contributed to the increasing suspi- Standing Bishop, attributed to Tilman cion that it was not of the period. -

Compositional Effects of Color

Open Palettes vs. Limited Palettes • Hue schemes can be generally divided into Open palettes and Limited palettes. Open Palettes vs. Limited Palettes • Open palettes allow any hue to be present — whether naturalistic color or randomly selected hues or expressive- intuitively selected hues are used. • Limited Palettes confine the hues used to some pre- planned strategy. Structured hue schemes (e.g. analogous, complementary, triadic, etc.) are limited-hue-plans that confine colors to only a few hues based upon a structure that selects hues by their relative positions on a hue wheel. Open Palette- vs.- Limited Palette vs. Structured Palette • Limited Palette concept simply acknowledges that only a small selection of colors are used. Typically, but not always, involving a structured palette. • Structured Palette concept refers to the usual “color schemes” — that is, a “structure” of monochromatic, or of Complementary, or split complementary hue selections. The hues that are used in the palette are selected according to some scheme, plan or structure. • Open Palette is an un-structured palette. Hues may be selected from any region of the color wheel. No structure is intentionally planned or imposed. Colors are most often applied intuitively, rather than analytically. Open Palette • (p. 53) A color scheme that uses hues from all over the color wheel. • The risk: Potentially chaotic and disunified. • The potential: often rich & visually dynamic. • A strategy: When an open palette is daringly used, some other characteristics of the design must provide unity – to hold it all together. Often a simple value pattern is used. [see Matisse and the Fauves] Variety, Chaos, & Fragmentation – dissolving unity • Some designers choose to let go of any planned or structured color scheme. -

Color Theory

color theory What is color theory? Color Theory is a set of principles used to create harmonious color combinations. Color relationships can be visually represented with a color wheel — the color spectrum wrapped onto a circle. The color wheel is a visual representation of color theory: According to color theory, harmonious color combinations use any two colors opposite each other on the color wheel, any three colors equally spaced around the color wheel forming a triangle, or any four colors forming a rectangle (actually, two pairs of colors opposite each other). The harmonious color combinations are called color schemes – sometimes the term 'color harmonies' is also used. Color schemes remain harmonious regardless of the rotation angle. Monochromatic Color Scheme The monochromatic color scheme uses variations in lightness and saturation of a single color. This scheme looks clean and elegant. Monochromatic colors go well together, producing a soothing effect. The monochromatic scheme is very easy on the eyes, especially with blue or green hues. Analogous Color Scheme The analogous color scheme uses colors that are adjacent to each other on the color wheel. One color is used as a dominant color while others are used to enrich the scheme. The analogous scheme is similar to the monochromatic, but offers more nuances. Complementary Color Scheme The complementary color scheme consists of two colors that are opposite each other on the color wheel. This scheme looks best when you place a warm color against a cool color, for example, red versus green-blue. This scheme is intrinsically high-contrast. Split Complementary Color Scheme The split complementary scheme is a variation of the standard complementary scheme. -

Trademark Registration of Product Colors: Issues and Answers Lee Burgunder

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 26 Article 3 Number 3 Combined Issues No. 3-4 1-1-1986 Trademark Registration of Product Colors: Issues and Answers Lee Burgunder Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lee Burgunder, Trademark Registration of Product Colors: Issues and Answers, 26 Santa Clara L. Rev. 581 (1986). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol26/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRADEMARK REGISTRATION OF PRODUCT COLORS: ISSUES AND ANSWERS Lee Burgunder* I. INTRODUCTION In October, 1985, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals held that Owens-Corning was entitled to register the color "pink" as a trademark for its fibrous glass residential insulation.' Yet, before this date, the law was well-settled that an overall product color could not be appropriated as a trademark.' Thus, one might think that the Owens-Corning decision represented a controversial turning point in trademark theory with respect to the federal registration of colors. In reality, however, the decision merely marked one more step on the path of confusion upon which the courts recently have been treading in the field of product color trademark registration. Currently, courts focus on the "functionality" of colors in trade- 8 mark cases. In light of the demands of competition in a free-market © 1986 by Lee Burgunder * Associate Professor of Law, California Polytechnic State University. -

R Color Cheatsheet

R Color Palettes R color cheatsheet This is for all of you who don’t know anything Finding a good color scheme for presenting data about color theory, and don’t care but want can be challenging. This color cheatsheet will help! some nice colors on your map or figure….NOW! R uses hexadecimal to represent colors TIP: When it comes to selecting a color palette, Hexadecimal is a base-16 number system used to describe DO NOT try to handpick individual colors! You will color. Red, green, and blue are each represented by two characters (#rrggbb). Each character has 16 possible waste a lot of time and the result will probably not symbols: 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,A,B,C,D,E,F: be all that great. R has some good packages for color palettes. Here are some of the options “00” can be interpreted as 0.0 and “FF” as 1.0 Packages: grDevices and i.e., red= #FF0000 , black=#000000, white = #FFFFFF grDevices colorRamps palettes Two additional characters (with the same scale) can be grDevices comes with the base cm.colors added to the end to describe transparency (#rrggbbaa) installation and colorRamps topo.colors terrain.colors R has 657 built in color names Example: must be installed. Each palette’s heat.colors To see a list of names: function has an argument for rainbow colors() peachpuff4 the number of colors and see P. 4 for These colors are displayed on P. 3. transparency (alpha): options R translates various color models to hex, e.g.: heat.colors(4, alpha=1) • RGB (red, green, blue): The default intensity scale in R > #FF0000FF" "#FF8000FF" "#FFFF00FF" "#FFFF80FF“ ranges from 0-1; but another commonly used scale is 0- 255. -

The Costly Process of Registering and Defending Color Trademarks

SEEING RED, SPENDING GREEN: THE COSTLY PROCESS OF REGISTERING AND DEFENDING COLOR TRADEMARKS LAUREN TRAINA* A shoe has so much more to offer than just to walk. —Christian Louboutin1 I. INTRODUCTION As demonstrated by the recent Second Circuit decision in Christian Louboutin v. Yves Saint Laurent America Holding, Inc.,2 a shoe can certainly offer a great deal of legal controversy. In September 2012, the Second Circuit upheld the validity of designer Christian Louboutin’s trademark for the color red on the soles of his shoes.3 Although Christian Louboutin and the fashion media have called the case a victory for color trademarks,4 Louboutin’s affirmation of the “aesthetic functionality” doctrine will likely make defending color trademarks harder in the future. Further, a survey of color trademark registration activity and case law reveals that the Louboutin decision is an outlier, and the overwhelming * Class of 2014, University of Southern California Gould School of Law; B.S., Business Administration, University of Southern California. I thank my parents, Joel and Vicki, and my sister, Nicole, for their unwavering support. I thank Professor Jonathan Barnett for his guidance throughout the writing process and Evan Scholm for his assistance in editing. 1. Lauren Collins, Sole Mate: Christian Louboutin and the Psychology of Shoes, NEW YORKER Mar. 28, 2011, at 83, 83, available at http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/03/28/sole-mate. 2. Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent Am. Holdings, Inc., 696 F.3d 206 (2d. Cir. 2012). 3. Id. at 212. 4. See, e.g.,Tamlin H. Bason, Both Sides Claim Victory as 2nd Cir. -

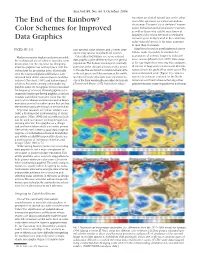

The End of the Rainbow? Color Schemes for Improved Data Graphics

Eos,Vol. 85, No. 40, 5 October 2004 receptors are shifted toward one or the other The End of the Rainbow? end of the spectrum are called anomalous trichromats.The term “color deficient”encom- passes dichromats and anomalous trichromats, Color Schemes for Improved as well as those who exhibit rarer forms of impaired color vision. Because a sex-linked Data Graphics recessive gene is implicated in the condition, color-vision deficiency is far more common in men than in women. PAGES 385, 391 one spectral color scheme, and a better alter- Algorithms based on psychophysical obser- native, may appear to color-blind readers. vations make it possible to simulate the appearance of colored images to color-defi- Modern computer displays and printers enable Color-blind individuals see some colored cient viewers [Brettel et al., 1997]. Data maps the widespread use of color in scientific com- data graphics quite differently from the general munication, but the expertise for designing population.The human visual system normally of the type shown here serve two main purposes: effective graphics has not kept pace with the perceives color through photosensitive cones detection of large-scale patterns and determi- technology for producing them. Historically, in the eye that are tuned to receive wavelengths nation of specific grid-cell or point values.The even the most prestigious publications have in the red,green,and blue portions of the visible saturated spectral scale (Figure 1a) creates a tolerated high defect rates in figures and illus- spectrum. People who lack cones sensitive to region of confusion centered on the North trations [Cleveland, 1984], and technological one of the three wavelengths are called dichromats American continent where achieving either advances that make creating and reproducing [Fortner and Meyer, 1997]. -

SAS/GRAPH ® Colors Made Easy Max Cherny, Glaxosmithkline, Collegeville, PA

Paper TT04 SAS/GRAPH ® Colors Made Easy Max Cherny, GlaxoSmithKline, Collegeville, PA ABSTRACT Creating visually appealing graphs is one of the most challenging tasks for SAS/GRAPH users. The judicious use of colors can make SAS graphs easier to interpret. However, using colors in SAS graphs is a challenge since SAS employs a number of different color schemes. They include HLS, HSV, RGB, Gray-Scale and CMY(K). Each color scheme uses different complex algorithms to construct a given color. Colors are represented as hard-to-understand hexadecimal values. A SAS user needs to understand how to use these color schemes in order to choose the most appropriate colors in a graph. This paper describes these color schemes in basic terms and demonstrates how to efficiently apply any color and its variation to a given graph without having to learn the underlying algorithms used in SAS color schemes. Easy and reusable examples to create different colors are provided. These examples can serve either as the stand-alone programs or as the starting point for further experimentation with SAS colors. SAS also provides CNS and SAS registry color schemes which allow SAS users to use plain English words for various shades of colors. These underutilized schemes and their color palettes are explained and examples are provided. INTRODUCTION Creating visually appealing graphs is one of the most challenging tasks for SAS users. Tactful use of color facilitates the interpretation of graphs by the reader. It also allows the writer to emphasize certain points or differentiate various aspects of the data in the graph. -

Assignment 4: Raw Material

Computer Science E-7: Exposing Digital Photography Harvard Extension School Fall 2010 Raw Material Assignment #4. Due 5:30PM on Tuesday, November 23, 2010. Part I. Pick Your Brain! (40 points) Type your answers for the following questions in a word processor; we will accept Word Documents (.doc, .docx), PDF documents (.pdf), or plaintext files (.txt, .rtf). Do not submit your answers for this part to Flickr. Instead, before the due date, attach the file to an email and send it to us at this address: ! [email protected] 1. (2 points) What are two advantages of JPEG over RAW? 2. (2 points) Which color space should you employ for general use? 3. (2 points) Why is white balance measured in degrees Kelvin? 4. (2 points) List two reasons why batteries in digital SLRs tend to last longer than those in compact digital cameras. 5. (2 points) Why is calibrating your monitor important? 6. (3 points) What is a tone curve and why is it necessary? 7. (3 points) Many digital cameras are advertised as having a crop factor. What does this mean? What are some of its advantages and disadvantages? 8. (3 points) Assume you have two sources of light: incandescent light at an approximate color temperature of 3000 K, and the sun with an approximate color temperature of 6000 K. Which source produces warmer tones? If you take two properly-exposed photographs of a white sheet of paper, one photo in each scene, with your camera set at a white balance of 4500 K, in which photo would the paper appear warmer? 1 of 6 Computer Science E-7: Exposing Digital Photography Harvard Extension School Fall 2010 9. -

COLORS of NATURE / KIT 3 How Do Art and Science Help Us Understand the World Around Us?

Kit 3 / Overview COLORS OF NATURE / KIT 3 KIT 3 OVERVIEW KIT 3 OVERVIEW BIOLOGY AND ART KIT 3 OVERVIEW HOW DOES COLOR HELP US UNDERSTAND THE LIVING WORLD AROUND US? The Colors of Nature Kits are designed to help students explore the question: how do art and science help us understand the world around us? Through a series of investigations students become familiar with core practices of art and science, developing scientific and artistic habits of mind that empower them to engage in self-directed inquiry through the generation and evaluation of ideas. Kit 3 explores this question through the lens of art and biology: the study of life and living organisms. A STEAM APPROACH TO EDUCATION (Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, Math) STEAM is an educational philosophy that seeks to balance the development of divergent and convergent thinking by integrating the arts with traditional STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math). In the STEAM approach to learning, students engage in projects and experiments that reflect the transdisciplinary nature of real-world problem solving. Rather than focusing on the delivery and memorization of content as isolated facts or repetition of rote procedures, STEAM seeks to develop scientific and artistic habits of mind and the confidence to engage in self-directed inquiry by familiarizing students with the core practices of art and science in an open and exploratory environment. The STEAM investigations in this kit are designed to foster creative engagement by promoting individual agency and establishing meaningful connections to students’ own lives. For additional teaching resources visit www.colorsofnature.org Kit 3 / Overview / Page 2 COLORS OF NATURE / KIT 3 How do art and science help us understand the world around us? INTRODUCTION / FOSTERING ENGAGEMENT IN ART AND SCIENCE STEAM ART / SCIENCE OVERLAP ENGAGEMENT IN SCIENCE PRACTICE Both science and art seek to broaden our Young children engage naturally in core science Around age 9, as social awareness increases, children understanding of the world around us. -

Paint Schemes & Color Samples

CAUTION: These colors are probably darker or lighter than you think. You should view a paint chip before specifying these colors on a remodeling or construction job. PAINT SCHEMES & COLOR SAMPLES As prepared by Carol Hearne, Salmon-Challis National Forest Heritage Program in “Excerpts from The 1946 Revision of the Building Construction Handbook for the Intermountain Region” November 2000 According to the 1946 revision of the R4 Building Construction Handbook, “The color scheme which will prevail for exteriors for Region 4 structures will be controlled by the predominant cover type in the immediate vicinity or, as will sometimes be the case, by exposed rock or earth, or by surrounding buildings or other conditions. The color scheme selected will be used on the exterior of all improvements at the site, including posts, flag pole, fences, and recreational equipment, provided they are to be stained or painted at all. Use only one body color, one trim color, and one roof color for all buildings located within a compound.” The R4 color schemes and their appropriate settings are: Color Scheme 1 Conifers; Log buildings in all cover types except when color scheme #5 applies Color Scheme 2 Aspen, Maple, Cottonwood Color Scheme 3 Sage, Open Prairie or Grass, Willow, Oak, Large Brush and Birch Color Scheme 4 In towns generally (Except buildings located in a setting or close to a background preponderantly conifers.) Color Scheme 5 Special color schemes designed by the Regional Office to deal with unique cover types, or with buildings or compounds that present particular challenges. As Carol Hearne notes in “Excerpts from The 1946 Revision of the Building Construction Handbook for the Intermountain Region”: “The main objective of this excerpt is to provide Forest Service personnel with good representative color samples that are comparable to original colors selected for ca.