Commentary on the Kathopanishad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vaishvanara Vidya.Pdf

VVAAIISSHHVVAANNAARRAA VVIIDDYYAA by Swami Krishnananda The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India (Internet Edition: For free distribution only) Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org CONTENTS Publishers’ Note 3 I. The Panchagni Vidya 4 The Course Of The Soul After Death 5 II. Vaishvanara, The Universal Self 26 The Heaven As The Head Of The Universal Self 28 The Sun As The Eye Of The Universal Self 29 Air As The Breath Of The Universal Self 30 Space As The Body Of The Universal Self 30 Water As The Lower Belly Of The Universal Self 31 The Earth As The Feet Of The Universal Self 31 III. The Self As The Universal Whole 32 Prana 35 Vyana 35 Apana 36 Samana 36 Udana 36 The Need For Knowledge Is Stressed 37 IV. Conclusion 39 Vaishvanara Vidya Vidya by by Swami Swami Krishnananda Krishnananda 21 PUBLISHERS’ NOTE The Vaishvanara Vidya is the famous doctrine of the Cosmic Meditation described in the Fifth Chapter of the Chhandogya Upanishad. It is proceeded by an enunciation of another process of meditation known as the Panchagni Vidya. Though the two sections form independent themes and one can be studied and practised without reference to the other, it is in fact held by exponents of the Upanishads that the Vaishvanara Vidya is the panacea prescribed for the ills of life consequent upon the transmigratory process to which individuals are subject, a theme which is the central point that issues from a consideration of the Panchagni Vidya. This work consists of the lectures delivered by the author on this subject, and herein are reproduced these expositions dilating upon the two doctrines mentioned. -

August 2009 1 2 the Divine Life August 2009

AUGUST 2009 1 2 THE DIVINE LIFE AUGUST 2009 PRACTISE SADHANA AS IN THE PRASTHANATRAYI (H.H. Sri Swami Sivanandaji Maharaj) Sri Veda Vyasa has done unfor get t a ble ser - eration the dif ferent as pects of ac tion, emo- vice to all human ity for all times by ed it ing the tion, will and under st and ing of which man is four Vedas, writing the Puranas, the an embodi ment. It is Brahmavidya and Yoga Mahabharata and the Brahma Sutras. We Sastra—theory as well as its prac tice. It is can at tempt to rep ay this debt of grati tude we KrishnarjunaSamv ada, the meeting of the in - owe him only by con stant study of his works di vidual and the Supreme. The Gita is not a and prac tice of his teach ings imp arted for the book of meta physi cal the ory, but is a guide for regen era tion of human ity in this Iron Age or the spir i tual man in his daily life of conscious Kali Yuga. In honour of this di vine person age self-ef fort for at tain ing Per fec tion. While the all Sadhakas and devo tees perform Vyasa path of pure knowledge is pos si ble only for Puja on the full-moon day in the month of the highly cultured man, the method of the Ashadha (July-August). Hence the day is Gita is sim ple, which is within the reach of all, called Vyasa Purnima or Guru Purnima. -

Brahma Sutra

BRAHMA SUTRA CHAPTER 1 1st Pada 1st Adikaranam to 11th Adhikaranam Sutra 1 to 31 INDEX S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No Summary 5 Introduction of Brahma Sutra 6 1 Jijnasa adhikaranam 1 a) Sutra 1 103 1 1 2 Janmady adhikaranam 2 a) Sutra 2 132 2 2 3 Sastrayonitv adhikaranam 3 a) Sutra 3 133 3 3 4 Samanvay adhikaranam 4 a) Sutra 4 204 4 4 5 Ikshatyadyadhikaranam: (Sutras 5-11) 5 a) Sutra 5 324 5 5 b) Sutra 6 353 5 6 c) Sutra 7 357 5 7 d) Sutra 8 362 5 8 e) Sutra 9 369 5 9 f) Sutra 10 372 5 10 g) Sutra 11 376 5 11 2 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 6 Anandamayadhikaranam: (Sutras 12-19) 6 a) Sutra 12 382 6 12 b) Sutra 13 394 6 13 c) Sutra 14 397 6 14 d) Sutra 15 407 6 15 e) Sutra 16 411 6 16 f) Sutra 17 414 6 17 g) Sutra 18 416 6 18 h) Sutra 19 425 6 19 7 Antaradhikaranam: (Sutras 20-21) 7 a) Sutra 20 436 7 20 b) Sutra 21 448 7 21 8 Akasadhikaranam : 8 a) Sutra 22 460 8 22 9 Pranadhikaranam : 9 a) Sutra 23 472 9 23 3 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 10 Jyotischaranadhikaranam : (Sutras 24-27) 10 a) Sutra 24 486 10 24 b) Sutra 25 508 10 25 c) Sutra 26 513 10 26 d) Sutra 27 517 10 27 11 Pratardanadhikaranam: (Sutras 28-31) 11 a) Sutra 28 526 11 28 b) Sutra 29 538 11 29 c) Sutra 30 546 11 30 d) Sutra 31 558 11 31 4 SUMMARY Brahma Sutra Bhasyam Topics - 191 Chapter – 1 Chapter – 2 Chapter – 3 Chapter – 4 Samanvaya – Avirodha – non – Sadhana – spiritual reconciliation through Phala – result contradiction practice proper interpretation Topics - 39 Topics - 47 Topics - 67 Topics 38 Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics 1 11 1 13 1 06 1 14 2 07 2 08 2 08 2 11 3 13 3 17 3 36 3 06 4 08 4 09 4 17 4 07 5 Lecture – 01 Puja: • Gratitude to lord for completion of Upanishad course (last Chandogya Upanishad + Brihadaranyaka Upanishad). -

Essays in Philosophy and Yoga

13 Essays in Philosophy and Yoga VOLUME 13 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO © Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 1998 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Essays in Philosophy and Yoga Shorter Works 1910 – 1950 Publisher's Note Essays in Philosophy and Yoga consists of short works in prose written by Sri Aurobindo between 1909 and 1950 and published during his lifetime. All but a few of them are concerned with aspects of spiritual philosophy, yoga, and related subjects. Short writings on the Veda, the Upanishads, Indian culture, politi- cal theory, education, and poetics have been placed in other volumes. The title of the volume has been provided by the editors. It is adapted from the title of a proposed collection, ªEssays in Yogaº, found in two of Sri Aurobindo's notebooks. Since 1971 most of the contents of the volume have appeared under the editorial title The Supramental Manifestation and Other Writings. The contents are arranged in ®ve chronological parts. Part One consists of essays published in the Karmayogin in 1909 and 1910, Part Two of a long essay written around 1912 and pub- lished in 1921, Part Three of essays and other pieces published in the monthly review Arya between 1914 and 1921, Part Four of an essay published in the Standard Bearer in 1920, and Part Five of a series of essays published in the Bulletin of Physical Education in 1949 and 1950. Many of the essays in Part Three were revised slightly by the author and published in small books between 1920 and 1941. -

By Veeraswamy Krishnaraj This Is Not the Official Site of Sri Guruvayoorappan Temple

By Veeraswamy Krishnaraj This is not the official site of Sri Guruvayoorappan Temple. Guruvayurappan Temple had a humble beginning in a hall in the said address several years ago, though its greatness was not any less than now. Then, it was a modest shrine; its grandeur is yet to manifest. The devotees saw the girders rise against the azure sky with fluffy clouds. The building rose around the steel girders through rain, shine, storm and snow in the middle of the woods to the delight of the devotees and the astute planners. Its vista is spectacular. I tried to capture its beauty surrounded by verdant woods turning colors from spring to fall. The trees and the spring and the summer leaves bore witness to the devotees coming and going with reverence in their hearts. As the rains came down from the heavens, each leaf shed its tears of joy to see the temple rise from mother earth. The temple bears rainbow colors on its exterior and its architecture is wonderful. Could this location be Brindavanam of North America? Could this have been where Krishna sported with Gopis in His youth. Such thoughts come up in the mind. See the splash of colors in this portrait bearing witness to the colorful persona of Bhagavan Krishna. The Morganville Temple the namesake of Gurvayur Sri Krishna Temple in Kerala houses Guruvayoorappan as the central deity. Its broad appeal is that the temple houses other deities. The presiding deity is MahaVishnu in the form of Krishna with Tulasi garland, in standing posture with four hands carrying Sankhu (conch), Sudarshana chakram (a serrated disk), lotus and mace. -

28Th Mahasamadhi Camp (2021) Yagna Prasad Pustika

28th Chinmaya Mahasamadhi Aradhana Camp Live Life with a Mission -with a Vision Universal Prayer O Adorable Lord of Mercy and Love! Salutations and prostrations unto Thee. Thou art Omnipresent, Omnipotent and Omniscient. Thou art Sat-Chid-Ananda. Thou art Existence, Knowledge and Bliss Absolute. Thou art the Indweller of all beings. Grant us an understanding heart, Equal vision, balanced mind, Faith, devotion and wisdom. Grant us inner spiritual strength To resist temptation and to control the mind. Free us from egoism, lust, anger, greed, hatred and jealousy. Fill our hearts with divine virtues. Let us behold Thee in all these names and forms. Let us serve Thee in all these names and forms. Let us ever remember Thee. Let us ever sing Thy glories. Let Thy Name be ever on our lips. Let us abide in Thee for ever and ever. Swami Sivananda 1 Clarity in vision, chastity in expression, and purity of action are sure signs of spiritual progress Swami Chinmayananda 2 Towards 2021 A.D, 28th Mahasamadhi Aradhana Camp, this souvenir is an offering of love and devotion from Chinmaya Mission San Jose to Pujya Gurudev Swami Chinmayananda 3 FOREWORD: PUJYA GURUJI ........................................................................... 5 PREFACE: SWAMI SWAROOPANANDA ........................................................... 7 VEDANTIC VISION: MAHAVAKYAS .................................................................. 8 VISION FROM OUR GURU PARAMPARA ....................................................... 11 ĀDI SHANKARĀCHĀRYA: RE-ESTABLISHING ADVAITA -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

India's Ancient Culture

INDIA’S ANCIENT CULTURE SWAMI KRISHNANANDA The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org Publishers’ Note This book consists of a series of 21 discourses that Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj gave to students in The Divine Life Society's Yoga Vedanta Forest Academy from November 1989 to January 1990. Swamiji Maharaj begins with the earliest stages of Indian culture, and discusses its evolution until the highest level of human achievement, which is liberation of the soul by the realisation of Brahman, the Absolute, through the stages of samadhi. 2 Table of Contents Publishers’ Note………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Chapter 1: The Definition of Culture ............................................................................................ 4 Chapter 2: The Evolution of Culture .......................................................................................... 11 Chapter 3: The Vedas – the Foundation of Indian Culture .............................................. 1 Chapter 4: The Fourfold Aim of and How to Achieve It ............................... 2 8 Chapter 5: Introduction to the Epics ......................................................................................... 3 Life ............ 7 Chapter 6: the Ramayana and the Mahabharata ..................... 4 7 Chapter 7: The Message of the Mahabharata ........................................................................ 5 Similarities between 6 Chapter 8: India’s Concept of Totality ..................................................................................... -

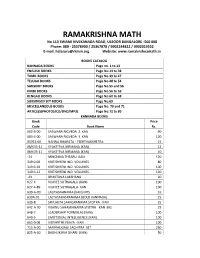

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

Bringing the Divine Down Into Man: the Building

Bringing the Divine down into Man: the building-up of the yoga path Trazendo o Divino para Dentro do Homem: a Construção do Sistema do Yoga Das Göttliche in den Menschen bringen: Die Konstruktion des Yoga Edrisi Fernandes 1 Resumo: O autor analisa a evolução do Yoga como uma disciplina ascética, desde o tempo da absorção dos habitantes originais da ?ndia pelas tribos arianas, que ali chegaram numa época proto-histórica. Ritos austeros, práticas mágicas, exercícios de controle respiratório e atitudes ascéticas dos habitantes locais foram incorporados na metafísica e na religião Védicas, e também no Yoga pré-clássico. A descoberta do poder das práticas ascéticas e meditacionais permitiu um distanciamento progressivo dos yogis em relação a práticas religiosas externas, tais como sacrifícios realizados com a intenção de favorecer os deuses, e a um avanço paralelo da visão do Yoga como um tipo de sacrifício em si mesmo, fundamentado na associação – entendida como uma ligação ou [re]união – entre o “Self”/a Alma vivente (âtman; jivâtman) do homem e a norma eterna (sanatana dharma), o “Senhor das Criaturas” (Prajâpati), o Ser Supremo (Parameshtin; Brahman; Shiva do Shaivismo; Vishnu do Vaishnavismo), ou a força ou poder (Shakti do Shaktismo [Tantrismo]) que torna a vida possível e que mantém o cosmos. Através de uma revisão do tema do Purusha (sânscrito para “pessoa; homem”, mas também para “Homem Universal; homem-deus”) em algumas referências clássicas da literatura indiana – incluindo o Rigveda, o Atharvaveda, muitos Upanishads, porções relevantes -

2018 January-February

Volume 40, issue 1, Page 1 On behalf of the 2017-2018 Executive Committee, we wish you a happy and prosperous new year. Our temple has grown almost double in the last 10 years and with that has come a welcomed change in how we do things. Having said that we can not abandon our way of governing as set forth in our current Constitution. Our goal this year is to become more efficient and transparent in how we operate. In doing so we have created emails for our officers and chairpersons of the Executive Committees. If you have any questions, suggestions, or comments, please email us by clicking PUJAS FOR JAN - on the Executive Committee name included in this newsletter and FEB posted on our website. GANESHA HAVAN J A N 1 On that list, you will see some familiar names and a few new S A N K A S T H I J A N 5 names. We hope this will encourage those of you who have a will- ingness to serve to come forward and let us know. KARTIKEYA PUJA J A N 6 KITE FESTIVAL J A N 7 A big thanks to all who completed the membership form during Di- wali. We have updated our database and hopefully all of you are SATHYANARAYANA J A N 1 2 & 31 now receiving the newsletter. The information you provide allows PUJA us to include your email for the newsletter and to provide you with KALYANOSTAV J A N 2 0 - 21 your charitable contribution notice. Don't forget to like and follow us SARASWATI PUJA J A N 2 7 on Facebook. -

Essence of Sanatsujatiya of Maha Bharata

ESSENCE OF SANATSUJATIYA OF MAHA BHARATA Translated, interpreted and edited by V.D.N.Rao 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu, Matsya, Varaha, Kurma, Vamana, Narada, Padma; Shiva, Linga, Skanda, Markandeya, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma, Brahma Vaivarta, Agni, Bhavishya, Nilamata; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa- Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama:a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri;b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata;c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti- Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima- Essence of Ashtaadasha Upanishads: Brihadarankya, Katha, Taittiriya/ Taittiriya Aranyaka , Isha, Svetashvatara, Maha Narayana and Maitreyi, Chhadogya and Kena, Atreya and Kausheetaki, Mundaka, Maandukya, Prashna, Jaabaala and Kaivalya. Also ‗Upanishad Saaraamsa‘ - Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti -Essence of Brahma Sutras- Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Essence of Knowledge of Numbers for students-Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and AusteritiesEssence of Manu Smriti- Quintessence of Manu Smriti- Essence of Paramartha Saara; Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskra; Essence of Pratyaksha Chandra; Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi; Essence