Roman-Letter Spelling of Toponyms from Other Wrfting Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petzl Rig Compact Self- Braking Descender

Petzl Rig Compact Self- braking Descender Brand:Petzl Options Code Description Price C6286 Yellow $275.00 +GST C1115 Black $325.00 +GST Petzl Rig Compact Self-braking Descender Designed for rope access work (expert users only) Multi-function handle allows the user to: - unlock the rope and control the descent with the hand on the free end of the rope - position himself at the work station without having to tie off the device The automatic return system on the handle limits risks in case of an involuntary action by the user Handle storage position reduces the risk of snagging when the descender is being carried on the harness. The gate on the moving side plate helps prevent dropping the device and facilitates rope installation when passing intermediate anchors Pivoting cam facilitates taking up the slack in the rope. Can also be used to make a reversible haul system, and for short ascents (in conjunction with a FOOTAPE or FOOTCORD foot loop and an ASCENSION handled rope clamp). Lowers heavy loads up to 200 kg (only for expert users; more information on this technique in the technical advice at www.petzl.com) Available in two Colours: yellow and black Specifications Min. rope diameter: 10.5 mm Max. rope diameter: 11.5 mm Weight: 380 g Certifications: EN 341 classe A, CE EN 12841 type C, NFPA 1983 Technical Use, EAC Options D21A D21AN https://colorex.co.nz/shop/products/height-safety/ascenders-descenders/petzl-rig-compact-self -braking-descender/ Page 1 E & OE | Prices are subject to change without notice | Copyright - All Rights Reserved 1633083992 Colours yellow black Rope compatibility 10.5 to 11.5 mm 10.5 to 11.5 mm https://colorex.co.nz/shop/products/height-safety/ascenders-descenders/petzl-rig-compact-self -braking-descender/ Page 2 E & OE | Prices are subject to change without notice | Copyright - All Rights Reserved 1633083992. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

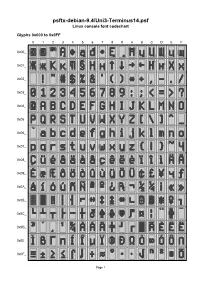

Psftx-Debian-9.4/Uni3-Terminus14.Psf Linux Console Font Codechart

psftx-debian-9.4/Uni3-Terminus14.psf Linux console font codechart Glyphs 0x000 to 0x0FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x00_ 0x01_ 0x02_ 0x03_ 0x04_ 0x05_ 0x06_ 0x07_ 0x08_ 0x09_ 0x0A_ 0x0B_ 0x0C_ 0x0D_ 0x0E_ 0x0F_ Page 1 Glyphs 0x100 to 0x1FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x10_ 0x11_ 0x12_ 0x13_ 0x14_ 0x15_ 0x16_ 0x17_ 0x18_ 0x19_ 0x1A_ 0x1B_ 0x1C_ 0x1D_ 0x1E_ 0x1F_ Page 2 Font information 0x013 U+049B CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KA WITH DESCENDER Filename: psftx-debian-9.4/Uni3-Terminus14.p sf 0x014 U+00B6 PILCROW SIGN PSF version: 1 0x015 U+00A7 SECTION SIGN Glyph size: 8 × 14 pixels Glyph count: 512 0x016 U+04A2 CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER Unicode font: Yes (mapping table present) EN WITH DESCENDER 0x017 U+04A3 CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER Unicode mappings EN WITH DESCENDER 0x000 U+00A9 COPYRIGHT SIGN 0x018 U+2191 UPWARDS ARROW, U+25B2 BLACK UP-POINTING 0x001 U+00AE REGISTERED SIGN TRIANGLE, U+25B4 BLACK UP-POINTING 0x002 U+2122 TRADE MARK SIGN SMALL TRIANGLE 0x003 U+0104 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER A 0x019 U+2193 DOWNWARDS ARROW, WITH OGONEK U+25BC BLACK DOWN-POINTING 0x004 U+2666 BLACK DIAMOND SUIT, TRIANGLE, U+25C8 WHITE DIAMOND U+25BE BLACK DOWN-POINTING CONTAINING BLACK SMALL SMALL TRIANGLE DIAMOND, 0x01A U+2192 RIGHTWARDS ARROW, U+FFFD REPLACEMENT U+25B6 BLACK RIGHT-POINTING CHARACTER TRIANGLE, 0x005 U+0105 LATIN SMALL LETTER A U+25B8 BLACK RIGHT-POINTING WITH OGONEK SMALL TRIANGLE 0x006 U+0111 LATIN SMALL LETTER D 0x01B U+2190 LEFTWARDS ARROW, WITH STROKE U+25C0 BLACK LEFT-POINTING TRIANGLE, 0x007 U+2022 BULLET, U+25C2 BLACK LEFT-POINTING U+25CF -

Alphabets, Letters and Diacritics in European Languages (As They Appear in Geography)

1 Vigleik Leira (Norway): [email protected] Alphabets, Letters and Diacritics in European Languages (as they appear in Geography) To the best of my knowledge English seems to be the only language which makes use of a "clean" Latin alphabet, i.d. there is no use of diacritics or special letters of any kind. All the other languages based on Latin letters employ, to a larger or lesser degree, some diacritics and/or some special letters. The survey below is purely literal. It has nothing to say on the pronunciation of the different letters. Information on the phonetic/phonemic values of the graphic entities must be sought elsewhere, in language specific descriptions. The 26 letters a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, o, p, q, r, s, t, u, v, w, x, y, z may be considered the standard European alphabet. In this article the word diacritic is used with this meaning: any sign placed above, through or below a standard letter (among the 26 given above); disregarding the cases where the resulting letter (e.g. å in Norwegian) is considered an ordinary letter in the alphabet of the language where it is used. Albanian The alphabet (36 letters): a, b, c, ç, d, dh, e, ë, f, g, gj, h, i, j, k, l, ll, m, n, nj, o, p, q, r, rr, s, sh, t, th, u, v, x, xh, y, z, zh. Missing standard letter: w. Letters with diacritics: ç, ë. Sequences treated as one letter: dh, gj, ll, rr, sh, th, xh, zh. -

Unicode Alphabets for L ATEX

Unicode Alphabets for LATEX Specimen Mikkel Eide Eriksen March 11, 2020 2 Contents MUFI 5 SIL 21 TITUS 29 UNZ 117 3 4 CONTENTS MUFI Using the font PalemonasMUFI(0) from http://mufi.info/. Code MUFI Point Glyph Entity Name Unicode Name E262 � OEligogon LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE OE WITH OGONEK E268 � Pdblac LATIN CAPITAL LETTER P WITH DOUBLE ACUTE E34E � Vvertline LATIN CAPITAL LETTER V WITH VERTICAL LINE ABOVE E662 � oeligogon LATIN SMALL LIGATURE OE WITH OGONEK E668 � pdblac LATIN SMALL LETTER P WITH DOUBLE ACUTE E74F � vvertline LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH VERTICAL LINE ABOVE E8A1 � idblstrok LATIN SMALL LETTER I WITH TWO STROKES E8A2 � jdblstrok LATIN SMALL LETTER J WITH TWO STROKES E8A3 � autem LATIN ABBREVIATION SIGN AUTEM E8BB � vslashura LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH SHORT SLASH ABOVE RIGHT E8BC � vslashuradbl LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH TWO SHORT SLASHES ABOVE RIGHT E8C1 � thornrarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER THORN LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C2 � Hrarmlig LATIN CAPITAL LETTER H LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C3 � hrarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER H LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C5 � krarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER K LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C6 UU UUlig LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE UU E8C7 uu uulig LATIN SMALL LIGATURE UU E8C8 UE UElig LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE UE E8C9 ue uelig LATIN SMALL LIGATURE UE E8CE � xslashlradbl LATIN SMALL LETTER X WITH TWO SHORT SLASHES BELOW RIGHT E8D1 æ̊ aeligring LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH RING ABOVE E8D3 ǽ̨ aeligogonacute LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH OGONEK AND ACUTE 5 6 CONTENTS -

Special Characters in Aletheia

Special Characters in Aletheia Last Change: 28 May 2014 The following table comprises all special characters which are currently available through the virtual keyboard integrated in Aletheia. The virtual keyboard aids re-keying of historical documents containing characters that are mostly unsupported in other text editing tools (see Figure 1). Figure 1: Text input dialogue with virtual keyboard in Aletheia 1.2 Due to technical reasons, like font definition, Aletheia uses only precomposed characters. If required for other applications the mapping between a precomposed character and the corresponding decomposed character sequence is given in the table as well. When writing to files Aletheia encodes all characters in UTF-8 (variable-length multi-byte representation). Key: Glyph – the icon displayed in the virtual keyboard. Unicode – the actual Unicode character; can be copied and pasted into other applications. Please note that special characters might not be displayed properly if there is no corresponding font installed for the target application. Hex – the hexadecimal code point for the Unicode character Decimal – the decimal code point for the Unicode character Description – a short description of the special character Origin – where this character has been defined Base – the base character of the special character (if applicable), used for sorting Combining Character – combining character(s) to modify the base character (if applicable) Pre-composed Character Decomposed Character (used in Aletheia) (only for reference) Combining Glyph -

Russian Language Resources

Russian Articles: Kagan, O., & Dillon, K. (2001). A new perspective on teaching Russian: Focus on the heritage learner. The Slavic and East European Journal, 45(3), 507-518. Kagan, O., & Dillon, K. (2006). Russian heritage learners: So what happens now? The Slavic and East European Journal, 50(1), 83-96. Leaver, B.L. (1984). Twenty minutes to mastery of the Cyrillic alphabet. Foreign Language Annals, 17(3), 215-220. Poritsky, E.F. (1990). Russian and the pre-literate language learner: On the development of a methodology. Foreign Language Annals, 22(3), 219-222. Thompson, I. & Rubin, J. (1996). Can strategy instruction improve listening comprehension? Foreign Language Annals, 29(3), 331-342. Assessment: There are a number of formal proficiency assessment tests available for Russian on the Center for Applied Linguistics’ website: http://www.cal.org/CALWebDB/FLAD/FLADListing.aspx. Olympiada of Spoken Russian: http://www.americancouncils.org/programDetail.php?program_id=NTg. Books: Grammar reviews: Dunn, J. & Khairov, S. (2009). Modern Russian grammar: A practical guide. New York: Routledge. Levine, J. (2009). Schaum’s outline of Russian grammar, Second edition. Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill. Словообразование (word-building): Patrick, G. Z. (1989) Roots of the Russian language: An elementary guide to wordbuilding. Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill. Textbooks: Elementary School: Ivanishko, I. (2011). I learn Russian: A children’s reading book. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. Ivanishko, I. (2012). I learn Russian: A grammar book for children (and adults too). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. Ivanishko, I. (2011). I learn Russian: Fun activities book. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. Kudela, K.R. (2011). My first book of Russian words. -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

Carwell Catalogue 2019-PDF.Pdf

江苏卡韦尔汽车部件有限公司位于江苏省丹阳市,主要从事汽车电子风扇、4X4改装件、汽车外观件生产 和销售,公司团队拥有15年专业行业经验。 主要经营产品 电子风扇-适用于韩系、日系和美系车型 4x4改装件-适用于欧系、日系和美系车型,如大众、丰田、福特、道奇、吉普和雪佛兰车型 汽车外观件-适用于韩系和日系车 卡韦尔为海外客户提供专业的性价比,高的汽车配件服务,我们相信在双方互信的基础上通过经营我们在 产品实现双赢! Jiangsu Carwell Automobile Co.,Ltd. locates in Danyang City,Jisangsu Province has professional team who have more than 15 years experience on Radiator fans, 4x4 Accessories.It’s mainly specialized in Radiator fans,Motors,SUV and Pick up 4x4 accessories,Exterior accessories. The Mainly Business Scope —Radiator Fans,Motor, for Korean Cars,Japanese Cars, American Cars etc. —SUV&Pick up 4x4 Accessories, for Europe Cars,Japanese Cars, American Cars like Volkswagen,Toyota,Nissan,Ford,RAM,JEEP Chevrolet etc. —Car Exterior accessories for Korean Cars,Japanese Cars Carwell provides oversea customers with best quality and most competitive price productions. Believing the prefect production will win-win for both parties based on mutual trust. CONTENTS… 目录 DAEWOO ……………………………………………………………………………………… 大宇 1 CHEVROLET ……………………………………………………………………………………… 雪佛兰 2.7 HYUNDAI ……………………………………………………………………………………… 现代 8.15 KIA ……………………………………………………………………………………… 起亚 16.19 TOYOTA ……………………………………………………………………………………… 丰田 20.24 HONDA ……………………………………………………………………………………… 本田 25.30 NISSAN ……………………………………………………………………………………… 尼桑 31.33 MITSUBISHI ……………………………………………………………………………………… 三菱 34.35 MAZDA ……………………………………………………………………………………… 马自达 36.38 FORD 福特 ……………………………………………………………………………………… 39.43 PEUGEOT ……………………………………………………………………………………… 标志 44 OPEL ……………………………………………………………………………………… 欧宝 45.46 FIAT -

|-- Eozo Oe F.G. 6 Gaara Eoz

Dec. 6, 1949 M. S. DUNKELBERGER 2,490,583 COMPOSITE FISHHOOK Filed March 4, 1944 44 42 |-- eozo Oe F.G. 6 GaAra eoz F. G. 3 Patented Dec. 6, 1949 2,490,583 UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE *2,490,583 COMPOSITE FISHOOK Milton S. Dunkelberger, Dayton, Ohio, assignor to Thea corporation American of Display Ohio Company, Dayton, Ohio, Application March 14, 1944-serial No.526,401 8 Claims. (Cl. 43-27) 2 This invention relates to a fish-hook assembly closed in my United States: Letters Patent No. and more particularly to a composite fishhook 2,334,613 issued November 16, 1943, for Fish-hook. that may be disassembled for storage. Each fish-hook is provided with a barb 14. The An object of this invention is to provide a com hooksportion 2 is preferably deflected from the posite fish-hook assembly that is produced from plane of the original stamping, so that the fish few parts, easily manufactured and assembled hook assembly has a spiral-like twist to the hooks. So as to produce a fish-hook assembly that is The upper-end of the hook is provided with a sturdy, dependable and efficient and that may neck; portion 6 terminating in a head 7 in be disassembled and put into a small kit snugly cluding a pair of lugs or ears of 8 and 20. The holding the parts, so as to be adapted for emer stems-or-shanks 0a of the hooks extend in Sub gency use. - - m stantially parallel-relation to each other and in Another object of this invention is to provide the same general direction. -

Writing System in Ukrainian

Some properties of the Ukrainian writing system Solomija Buk1, Lviv Ján Mačutek2, Bratislava Andrij Rovenchak3, Lviv Abstract. We investigate the grapheme–phoneme relation in Ukrainian and some properties of the Ukrainian version of the Cyrillic alphabet. Keywords: Ukrainian, phoneme-grapheme relation, script analysis. 1. Introductory remarks Ukrainian is an East Slavic language spoken by about 40 million people in Ukraine and Ukrainian communities in neighboring states (Belarus, Moldova, Poland, Slovakia, Russia — especially in the so-called Zelenyj Klyn ‘Green wedge’ in the Far East Siberia from the Amur and Ussuri rivers eastwards to the Pacific), also in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, USA, and some others. The features typical for modern Ukrainian are found already in the texts from 11th- 12th cent. AD, they have been appearing systematically since 14th-15th cent. (Rusanivsjkyj 2004). Ukrainian uses the Cyrillic script. The Cyrillic alphabet, also known as azbuka (from old names of its first two letters ( ) and ( )), has been traditionally used to write East and South Slavic languages (with the exception of modern Croatian and Slovenian), and also Romanian until 1860 (Jensen 1969: 491). As a result of political decisions it spread over a much larger area covering most (but not all) of languages in the former USSR, many of them using Latin or Arabic script before (cf. Comrie 1996b for a more detailed historical overview). Obviously, being applied in so different languages like Russian, Abkhaz, Tatar, Tajik or Chukchi (to give just a few examples) it had to represent much more phonemes than those occurring in Slavic languages, hence there are/were many language specific modifications of the alphabet (modified particular letters, diacritic marks or completely new letters, cf. -

Writing As Language Technology

HG2052 Language, Technology and the Internet Writing as Language Technology Francis Bond Division of Linguistics and Multilingual Studies http://www3.ntu.edu.sg/home/fcbond/ [email protected] Lecture 2 HG2052 (2021); CC BY 4.0 Overview ã The origins of writing ã Different writing systems ã Representing writing on computers ã Writing versus talking Writing as Language Technology 1 The Origins of Writing ã Writing was invented independently in at least three places: Mesopotamia China Mesoamerica Possibly also Egypt (Earliest Egyptian Glyphs) and the Indus valley. ã The written records are incomplete ã Gradual development from pictures/tallies Writing as Language Technology 2 Follow the money ã Before 2700, writing is only accounting. Temple and palace accounts Gold, Wheat, Sheep ã How it developed One token per thing (in a clay envelope) One token per thing in the envelope and marked on the outside One mark per thing One mark and a symbol for the number Finally symbols for names Denise Schmandt-Besserat (1997) How writing came about. University of Texas Press Writing as Language Technology 3 Clay Tokens and Envelope Clay Tablet Writing as Language Technology 4 Writing systems used for human languages ã What is writing? A system of more or less permanent marks used to represent an utterance in such a way that it can be recovered more or less exactly without the intervention of the utterer. Peter T. Daniels, The World’s Writing Systems ã Different types of writing systems are used: Alphabetic Syllabic Logographic Writing