Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Is a Pre-Copyedited, Author-Produced Version of an Article Accepted for Publication in Twentieth Century British History Following Peer Review

1 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Twentieth Century British History following peer review. The version of record, Brett Holman, ‘The shadow of the airliner: commercial bombers and the rhetorical destruction of Britain, 1917-35’, Twentieth Century British History 24 (2013), 495-517, is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/hws042. The shadow of the airliner: commercial bombers and the rhetorical destruction of Britain, 1917-19351 Brett Holman, Independent Scholar Aerial bombardment was widely believed to pose an existential threat to Britain in the 1920s and 1930s. An important but neglected reason for this was the danger from civilian airliners converted into makeshift bombers, the so-called ‘commercial bomber’: an idea which arose in Britain late in the First World War. If true, this meant that even a disarmed Germany 1 The author would like to thank: the referees, for their detailed comments; Chris A. Williams, for his assistance in locating a copy of Cd. 9218; and, for their comments on a draft version of this article, Alan Allport, Christopher Amano- Langtree, Corry Arnold, Katrina Gulliver, Wilko Hardenberg, Lester Hawksby, James Kightly, Beverley Laing, Ross Mahoney, Andre Mayer, Bob Meade, Andrew Reid, and Alun Salt. Figure 1 first appeared in the Journal of the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Vol, 8, No. 4, July 1929, pp, 289-317, and is reproduced with permission. 2 could potentially attack Britain with a large bomber force thanks to its successful civil aviation industry. By the early 1930s the commercial bomber concept appeared widely in British airpower discourse. -

Channel Islands Great War Study Group

CHANNEL ISLANDS GREAT WAR STUDY GROUP Le Défilé de la Victoire – 14 Juillet 1919 JOURNAL 27 AUGUST 2009 Please note that Copyright for any articles contained in this Journal rests with the Authors as shown. Please contact them directly if you wish to use their material. 1 Hello All It will not have escaped the notice of many of us that the month of July, 2009, with the deaths of three old gentlemen, saw human bonds being broken with the Great War. This is not a place for obituaries, collectively the UK’s national press has done that task more adequately (and internationally, I suspect likewise for New Zealand, the USA and the other protagonists of that War), but it is in a way sad that they have died. Harry Patch and Henry Allingham could recount events from the battles at Jutland and Passchendaele, and their recollections have, in recent years, served to educate youngsters about the horrors of war, and yet? With age, memory can play tricks, and the facts of the past can be modified to suit the beliefs of the present. For example, Harry Patch is noted as having become a pacifist, and to exemplify that, he stated that he had wounded, rather than killed, a German who was charging Harry’s machine gun crew with rifle and bayonet, by Harry firing his Colt revolver. I wonder? My personal experience in the latter years of my military career, having a Browning pistol as my issued weapon, was that the only way I could have accurately hit a barn door was by throwing the pistol at it! Given the mud and the filth, the clamour and the noise, the fear, a well aimed shot designed solely to ‘wing’ an enemy does seem remarkable. -

Sir Frank Cooper on Air Force Policy in the 1950S & 1960S

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society Copyright © Royal Air Force Historical Society, 1993 All rights reserved. 1 Copyright © 1993 by Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed by Hastings Printing Company Limited Royal Air Force Historical Society 2 THE PROCEEDINGS OFTHE ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Issue No 11 President: Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Committee Chairman: Air Marshal Sir Frederick B Sowrey KCB CBE AFC General Secretary: Group Captain J C Ainsworth CEng MRAeS Membership Secretary: Commander P O Montgomery VRD RNR Treasurer: D Goch Esq FCCA Programme Air Vice-Marshal G P Black CB OBE AFC Sub-Committee: Air Vice-Marshal F D G Clark CBE BA Air Commodore J G Greenhill FBIM T C G James CMG MA *Group Captain I Madelin Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Group Captain A R Thompson MBE MPhil BA FBIM MIPM Members: A S Bennell Esq MA BLitt *Dr M A Fopp MA PhD FMA FBIM A E Richardson *Group Captain N E Taylor BSc D H Wood Comp RAeS * Ex-officio The General Secretary Regrettably our General Secretary of five years standing, Mr B R Jutsum, has found it necessary to resign from the post and the committee. -

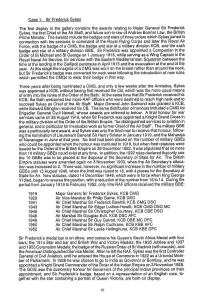

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes the First Display in the Gallery Contains

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes The first display in the gallery contains the awards relating to Major General Sir Frederick Sykes, the first Chief of the Air Staff, and future son-in-law of Andrew Bonnar Law, the British Prime Minister. The awards include the badges and stars of three orders which Sykes joined in connection with his services in command of the Royal Flying Corps and later the Royal Air Force, with the badge of a CMG, the badge and star of a military division KCB, and the sash badge and star of a military division GBE. Sir Frederick was appointed a Companion in the Order of St Michael and St George on 1 January 1916, while serving as a Wing Captain in the Royal Naval Air Service, for services with the Eastern Mediterranean Squadron between the time of the landing in the Gallipoli peninsula in April 1915 and the evacuation at the end of the year. At this stage the insignia of a CMG was worn on the breast rather than around the neck, but Sir Frederick’s badge was converted for neck wear following the introduction of new rules which permitted the CMGs to wear their badge in that way. Three years after being nominated a CMG, and only a few weeks after the Armistice, Sykes was appointed a KCB, without having first received the CB, which was the more usual means of entry into the ranks of the Order of the Bath. At the same time that Sir Frederick received his KCB, the Bath welcomed two more RAF officers who were destined to reach high rank and to succeed Sykes as Chief of the Air Staff: Major General John Salmond was granted a KCB, while Edward Ellington received his CB. -

Ii. Ausgangslage 1. Die Royal Air Force Am Ende Des Ersten Weltkriegs

II. AUSGANGSLAGE 1. DIE ROYAL AIR FORCE AM ENDE DES ERSTEN WELTKRIEGS 1.1 DER ERSTE WELTKRIEG Die Entwicklung des militärischen Flugwesens Im Verlauf der voranschreitenden Entwicklungen in der zivilen Luftfahrt wur- de die seit dem Jahr 1888 bestehende School of Ballooning am 1. April 1911 in ein Air Battalion als Teil der Royal Engineers reorganisiert. Diese Einheit, bestehend aus etwa 150 Mann, verwendete erstmals motorgetriebene Flugma- schinen für militärische Zwecke. Ihr erster Kommandeur war Major Sir Alex- ander Bannerman, dem ein Jahr darauf Major Frederick Sykes nachfolgte. Sykes war ein Befürworter des Einsatzes von Flugzeugen zu Aufklärungszwe- cken. Im gleichen Jahr wurde er vom Committee of Imperial Defence1 (CID) mit einer Untersuchung des Nutzens von Flugzeugen im Krieg betraut.2 Das War Office schickte den damaligen Captain nach Frankreich, wo er als Manö- verbeobachter den Wert von Flugzeugen bei militärischen Operationen beur- teilen sollte. Er war davon überzeugt, dass Flugzeuge künftig eine entschei- dende Rolle in der Kriegführung spielen würden und bereitete sich auch privat darauf vor. Sykes erlernte das Fliegen und belegte einen Kurs über Aerodyna- mik an der London University. Entsprechend positiv fiel sein Bericht nach den französischen Manövern aus. Er resümierte, dass ein Flugzeug Aufklärungs- ergebnisse in vier Stunden liefern konnte, wo eine Patrouille zu Pferd vier Tage benötigen würde: „There can no longer be any doubt as to the value of aero- planes in locating an enemy on land and obtaining information.“3 Der Bericht veranlasste die Entscheidungsträger zur Formierung eines Naval Wing, eines Military Wing, einer Central Flying School und einer Aircraft Factory.4 Zu- 1 Vom Beginn des 20. -

British Identity, the Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2019 A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image Abby S. Whitlock College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Whitlock, Abby S., "A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1276. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1276 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image Abby Stapleton Whitlock Undergraduate Honors Thesis College of William and Mary Lyon G. Tyler Department of History 24 April 2019 Whitlock !2 Whitlock !3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………….. 4 Introduction …………………………………….………………………………… 5 Chapter I: British Aviation and the Future of War: The Emergence of the Royal Flying Corps …………………………………….……………………………….. 13 Wartime Developments: Organization, Training, and Duties Uniting the Air Services: Wartime Exigencies and the Formation of the Royal Air Force Chapter II: The Cultural Image of the Royal Flying Corps .……….………… 25 Early Roots of the RFC Image: Public Imagination and Pre-War Attraction to Aviation Marketing the “Cult of the Air Fighter”: The Dissemination of the RFC Image in Government Sponsored Media Why the Fighter Pilot? Media Perceptions and Portrayals of the Fighter Ace Chapter III: Shaping the Ideal: The Early Years of Aviation Psychology .…. -

Victoria Cross Heroes of Wellingborough

1914–2014 FIRST WORLD WAR CENTENARY SOUVENIR ISSUE The Link www.wellingborough.gov.uk Summer 2014 Victoria Cross heroes of Wellingborough Major Edward Corringham ‘Mick’ Mannock VC DSO** MC* BRITAIN’S most successful fighter pilot during the First World War lived in Welling- borough. His job as a tele phone engineer led him to lodge at 183 Mill Road prior to the war. He joined the Royal Engineers in March 1916, where he was awarded a commission and be- came a second lieutenant. In August 1916 he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and was sent to the Western Front in April 1917. On 22 July 1917, Mannock Major Mannock was promoted to captain and he became a flight commander. Lt-Col The Rev Vann He gave his men 15 rules about flying in combat, which became the bedrock not only for the RFC but also for the fighter pilots of the RAF of the future. Mannock was a highly skilled pilot. On his medals. They are now on display at the Foresters in April 1915. He was awarded 16 August 1917, he shot down four German Imperial War Museum in London. the Military Cross for his efforts in Kemmel aeroplanes in one day. Edward Mannock was awarded the when a small trench he occupied was blown The next day he shot down two other Military Cross (MC) twice, was one of the up and, although wounded and half buried, German aeroplanes. rare three-times winners of a Distinguished he organised the defence and rescued buried On 20 July 1918, Mannock shot down his Service Order (DSO) and was posthumously men under heavy fire, refusing to leave his 58th ‘kill’, making him Britain’s highest- awarded the Victoria Cross. -

View of the British Way in Warfare, by Captain B

“The Bomber Will Always Get Through”: The Evolution of British Air Policy and Doctrine, 1914-1940 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Katie Lynn Brown August 2011 © 2011 Katie Lynn Brown. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled “The Bomber Will Always Get Through”: The Evolution of British Air Policy and Doctrine, 1914-1940 by KATIE LYNN BROWN has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Peter John Brobst Associate Professor of History Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT BROWN, KATIE LYNN, M.A., August 2011, History “The Bomber Will Always Get Through”: The Evolution of British Air Policy and Doctrine, 1914-1940 Director of Thesis: Peter John Brobst The historiography of British grand strategy in the interwar years overlooks the importance air power had in determining Britain’s interwar strategy. Rather than acknowledging the newly developed third dimension of warfare, most historians attempt to place air power in the traditional debate between a Continental commitment and a strong navy. By examining the development of the Royal Air Force in the interwar years, this thesis will show that air power was extremely influential in developing Britain’s grand strategy. Moreover, this thesis will study the Royal Air Force’s reliance on strategic bombing to consider any legal or moral issues. Finally, this thesis will explore British air defenses in the 1930s as well as the first major air battle in World War II, the Battle of Britain, to see if the Royal Air Force’s almost uncompromising faith in strategic bombing was warranted. -

By the Seat of Their Pants

BY THE SEAT OF THEIR PANTS THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE HELD AT THE RAAF MUSEUM , POINT COOK BY MILITARY HISTORY AND HERITAGE VICTORIA 12 NOVEMBER 2012 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AAC Australian Air Corps AFC Australian Flying Corps AIF Australian Imperial Force AWM Australian War Memorial CFS Central Flying School DFC Distinguished Flying Cross DSO Distinguished Service Order KIA Killed in Action MC Military Cross MM Military Medal NAA National Archives of Australia NAUK The National Archives of the UK NCO Non-Commissioned Officer POW Prisoner of War RAAF Royal Australian Air Force RFC Royal Flying Corps RNAS Royal Naval Air Service SLNSW State Library of New South Wales NOTES ON CONTRIBUTOR MR MICHAEL MOLKENTIN Michael is a PhD candidate at the University of New South Wales where he is writing a thesis titled ‘Australia, the Empire and the Great War in the Air’. His research will form the basis of a volume in the Australian Army’s Centenary History of the Great War series that Oxford University Press will publish in 2014. Michael is a qualified history teacher and battlefield tour guide and has worked as a consultant for programs screened on the ABC and Chanel 9. Michael has contributed articles to the Journal of the Australian War Memorial , Teaching History , Wartime , Cross & Cockade , Over the Front and Flightpath , and is the author of two books: Fire in the Sky: The Australian Flying Corps in the First World War (Allen & Unwin, 2010) and Flying the Southern Cross: Aviators Charles Ulm and Charles Kingsford Smith (National Library of Australia, 2012). -

Airmen-Ww1-8.Pdf

Grant A. Gooderham of Toronto in a BE2c at Chingford, Aug.-Sept. 1915. Note the Union Jack on the rudder, an identification marking that was soon dropped in favour of a tricolour roundel on the fuselage. (pMR 71-24) This poster, illustrating one of the best remembered catchphrases of a First World War pilot, was used to drive home to airmen the need to keep a careful look-out. (AH 559) Lt W.A. Bishop of Toronto {right) serving with the 8th Canadian Mounted Rifles at London, Ont., in February 1915. He subsequently went overseas with the CEF, then transferred to the RFC in December 1915. (RE 22064) A German observation balloon on the Western Front (AH 490) A captured Fokker E-111 at Candas, France, 20 April 1916 (PMR 73-500) The RNAS airfield at Furnes in July 1916. The Sopwith Triplane at left is probably the first prototype, N500, which was sent to Furnes in June to undergo operational trials. (PMR 71-40) A 1916 aerial photograph, clearly showing first, second, and third line German trenches, and, in the top right-hand corner, the communications trenches which linked them with the ruins of Beaumont Hamel. (O 61479) Morane-Saulnier Type L ' Parasols' of 3 Squadron, RFC, at La Houssaye in September 1916. When this picture was taken at least four Canadians- Lts K.A. Creery of Vancouver, W.W. Lang of Toronto, G.A.H. Trudeau of Longueuil, Que., and 2/Lt F.H. Whiteman of Kitchener, Ont. -were serving with the squadron. (AH 578) An observer in the basket of an artillery observation balloon on the Somme in September 1916 tests his telephone before ascending. -

THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING the BATTLE of the SOMME APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: a PYRRHIC VICTORY by Thomas G. Bradbeer M.A., Univ

THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: A PYRRHIC VICTORY By Thomas G. Bradbeer M.A., University of Saint Mary, 1999 Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________ Chairperson Theodore A. Wilson, PhD Committee members ____________________ Jonathan H. Earle, PhD ____________________ Adrian R. Lewis, PhD ____________________ Brent J. Steele, PhD ____________________ Jacob Kipp, PhD Date defended: March 28, 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Thomas G. Bradbeer certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: A PYRRHIC VICTORY ___________________ Chairperson Theodore A. Wilson, PhD Date approved March 28, 2011 ii THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME, APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: A PYRRHIC VICTORY ABSTRACT The Battle of the Somme was Britain’s first major offensive of the First World War. Just about every facet of the campaign has been analyzed and reexamined. However, one area of the battle that has been little explored is the second battle which took place simultaneously to the one on the ground. This second battle occurred in the skies above the Somme, where for the first time in the history of warfare a deliberate air campaign was planned and executed to support ground operations. The British Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was tasked with achieving air superiority over the Somme sector before the British Fourth Army attacked to start the ground offensive. -

Geographical Reconnaissance by Aeroplane Photography, With

Geographical Reconnaissance by Aeroplane Photography, with Special Reference to the Work Done on the Palestine Front: Discussion Author(s): Geoffrey Salmond, Coote Hedley, H. S. L. Winterbotham, A. R. Hinks and E. M. Jack Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 55, No. 5 (May, 1920), pp. 370-376 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1780447 Accessed: 25-06-2016 21:41 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 137.99.31.134 on Sat, 25 Jun 2016 21:41:03 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms 370 GEOGRAPHICAL RECONNAISSANCE BY the great utility of maps which are sufficiently complete in local features to enable one to identify one's position by reference to the map detail. Most of the pre-war reconnaissance maps which I have used in the East, and which would be probably regarded as good of their type, involved the need of constantly stopping to take bearings on some distant known points in order to ascertain one's position, and this is a tiresome proceeding.