Investigation of Whitewater Development Corporation and Related Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lloyd Cutler

White House Interview Program DATE: July 8, 1999 INTERVIEWEE: LLOYD CUTLER INTERVIEWER: Martha Kumar With Nancy Kassop MK: May we tape? LC: Yes, but I’d like to have one understanding. I have been misquoted on more than one occasion. I’ll be happy to talk to you about what I think about the transition but I don’t want my name attached to any of it. MK: Okay. So we’ll come back to you for any quotes. We’re going to look at both aspects: the transition itself and then the operations of the office. Working on the theory that one of the things that would be important for people is to understand how an effective operation works, what should they be aiming toward? For example, what is a smooth-running counsel’s office? What are the kinds of relationships that should be established and that sort of thing? So, in addition to looking at the transition, we’re just hoping they’re looking toward effective governance. In your time in Washington, observing many administrations from various distances, you have a good sense of transitions, what works and what doesn’t work. One of the things we want to do is isolate what are the elements of success—just take a number, six elements, five elements—that you think are common to successful transitions. What makes them work? LC: Well, the most important thing to grasp first is how much a White House itself, especially as it starts off after a change in the party occupying the White House, resembles a city hall. -

The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003

THE REGIME CHANGE CONSENSUS: IRAQ IN AMERICAN POLITICS, 1990-2003 Joseph Stieb A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Wayne Lee Michael Morgan Benjamin Waterhouse Daniel Bolger Hal Brands ©2019 Joseph David Stieb ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joseph David Stieb: The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003 (Under the direction of Wayne Lee) This study examines the containment policy that the United States and its allies imposed on Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War and argues for a new understanding of why the United States invaded Iraq in 2003. At the core of this story is a political puzzle: Why did a largely successful policy that mostly stripped Iraq of its unconventional weapons lose support in American politics to the point that the policy itself became less effective? I argue that, within intellectual and policymaking circles, a claim steadily emerged that the only solution to the Iraqi threat was regime change and democratization. While this “regime change consensus” was not part of the original containment policy, a cohort of intellectuals and policymakers assembled political support for the idea that Saddam’s personality and the totalitarian nature of the Baathist regime made Iraq uniquely immune to “management” strategies like containment. The entrenchment of this consensus before 9/11 helps explain why so many politicians, policymakers, and intellectuals rejected containment after 9/11 and embraced regime change and invasion. -

Clinton Bush Assassination Teams Revealed in Hillary's Emails

Clinton Bush Assassination Teams Revealed in Hillary’s emails Exclusive, explosive breaking reports from the patriot Joint U.S.-French Intelligence Task Force, operating on American soil for over 200 years. By Tom Heneghan International Intelligence Expert Sunday January 31 2016 Clinton – Bush Assassination Teams Revealed in Hillary emails UNITED States of America – It can now be reported that four (4) of the now classified TOP SECRET national security emails tied to the FBI investigation of former U.S. Secretary of State NAZI neocon Hillary Rodham Clinton deal with the existence of domestic political assassination teams headquartered in Albuquerque, New Mexico with a link to the NSA-administered E-Systems out of Dallas, Texas aka Bush NAZI ‘Skull and Bones’ headquarters. The emails include a hit list involving patriotic U.S. citizens referred to as “loud mouths” reference individuals that believe 9/11 was an inside job aka George W. BushFRAUD’s 9/11 NAZI German Adolf Hitler-style “Reichstag Fire”, that the war in Iraq was an illegal un Constitutional war crime that murdered millions of people and was designed to cover up the 9/11 coup d’ ‘etat versus the U.S. Constitution and the year 2000 NSA-E-Systems electoral coup d’ ‘etat versus the American People aka the year 2000 DULY ELECTED natural born REAL President of the United States, Albert Gore Jr. of Carthage, Tennessee. The hit list includes the names of the following: Yours truly, Thomas Heneghan http://www.tomheneghanbriefings.com Court adjudicated federal whistle blower Mary Schneider Federal Whistle blower Stew Webb and his attorney Bret Landrith http://www.stewwebb.com http://www.bretlandrith.com Current U.S. -

Reimbursing the Attorney's Fees of Current and Former Federal

(Slip Opinion) Reimbursing the Attorney’s Fees of Current and Former Federal Employees Interviewed as Witnesses in the Mueller Investigation The Department of Justice Representation Guidelines authorize, on a case-by-case basis, the reimbursement of attorney’s fees incurred by a current or former federal govern- ment employee interviewed as a witness in the Mueller Investigation under threat of subpoena about information the person acquired in the course of his government du- ties. October 7, 2020 MEMORANDUM OPINION FOR THE ACTING ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL CIVIL DIVISION You have asked for our opinion on the scope of the Attorney General’s authority to reimburse the attorney’s fees of federal employees who were interviewed as witnesses in connection with the investigation by Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller, III into possible Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election (“Mueller Investigation”). The Civil Division reviews requests for such reimbursement under long-standing Department of Justice (“Department”) regulations. See 28 C.F.R. §§ 50.15–50.16. You have asked specifically how certain elements of section 50.15 apply to the Mueller Investigation: (1) whether a person interviewed as a witness in the Mueller Investigation under threat of subpoena should be viewed as having been “subpoenaed,” id. § 50.15(a); (2) whether a witness inter- viewed about information acquired in the course of the witness’s federal employment appears in an “individual capacity,” id.; and (3) what factors should be considered in evaluating whether the reimbursement of the attorney’s fees of such a witness is “in the interest of the United States,” id. -

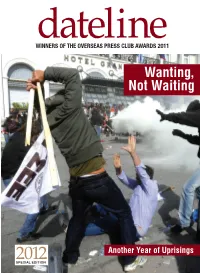

Wanting, Not Waiting

WINNERSdateline OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS 2011 Wanting, Not Waiting 2012 Another Year of Uprisings SPECIAL EDITION dateline 2012 1 letter from the president ne year ago, at our last OPC Awards gala, paying tribute to two of our most courageous fallen heroes, I hardly imagined that I would be standing in the same position again with the identical burden. While last year, we faced the sad task of recognizing the lives and careers of two Oincomparable photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, this year our attention turns to two writers — The New York Times’ Anthony Shadid and Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times of London. While our focus then was on the horrors of Gadhafi’s Libya, it is now the Syria of Bashar al- Assad. All four of these giants of our profession gave their lives in the service of an ideal and a mission that we consider so vital to our way of life — a full, complete and objective understanding of a world that is so all too often contemptuous or ignorant of these values. Theirs are the same talents and accomplishments to which we pay tribute in each of our awards tonight — and that the Overseas Press Club represents every day throughout the year. For our mission, like theirs, does not stop as we file from this room. The OPC has moved resolutely into the digital age but our winners and their skills remain grounded in the most fundamental tenets expressed through words and pictures — unwavering objectivity, unceasing curiosity, vivid story- telling, thought-provoking commentary. -

Senate (Legislative Day of Wednesday, February 28, 1996)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 142 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 1996 No. 26 Senate (Legislative day of Wednesday, February 28, 1996) The Senate met at 11 a.m., on the ex- Senator MURKOWSKI for 15 minutes, able to get this opportunity to go piration of the recess, and was called to Senator DORGAN for 20 minutes; fol- where they can get the help they order by the President pro tempore lowing morning business today at 12 need—perhaps after the regular school [Mr. THURMOND]. noon, the Senate will begin 30 minutes hours. Why would we want to lock chil- of debate on the motion to invoke clo- dren in the District of Columbia into PRAYER ture on the D.C. appropriations con- schools that are totally inadequate, The Chaplain, Dr. Lloyd John ference report. but their parents are not allowed to or Ogilvie, offered the following prayer: At 12:30, the Senate will begin a 15- cannot afford to move them around Let us pray: minute rollcall vote on that motion to into other schools or into schools even Father, we are Your children and sis- invoke cloture on the conference re- in adjoining States? ters and brothers in Your family. port. It is also still hoped that during Today we renew our commitment to today’s session the Senate will be able It is a question of choice and oppor- live and work together here in the Sen- to complete action on legislation ex- tunity. -

Vol IV Part F Ch. 1 DOJ Handling of the RTC Referrals

PART F THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE'S HANDLING OF THE RTC CRIMINAL REFERRALS AND THE CONTACTS BETWEEN THE WHITE HOUSE AND THE DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Chapter 1: DOJ Handling of the RTC Referrals I. INTRODUCTION The potential involvement of President Clinton with matters in criminal referral C-0004 raised questions about the proper handling of the referral by the Department of Justice. The referral identified him and Mrs. Clinton as potential witnesses to the alleged criminal conduct relating to Madison Guaranty by Jim McDougal. The delay in full consideration of the referral between September 1992 and the ultimate appointment of a regulatory independent counsel in January 1994 required investigation of whether any action during that time was intended to prevent full examination of the conduct alleged in the referral. Whether before or after the 1992 election of President Clinton, any action that had the effect of delaying or impeding the investigation could raise the question of whether anyone in the Department of Justice unlawfully obstructed the investigation in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1505. This investigation examined the conduct and motives of Department of Justice officials in a position to influence the handling of the referral. These officials included President Bush's U.S. Attorney in Little Rock, President Clinton's subsequent appointee as the U.S. Attorney, and officials at the Department of Justice headquarters in Washington D.C. both at the end of the Bush Administration and during the first year of the Clinton Administration. II. FINDINGS The Independent Counsel concluded the evidence was insufficient to prove that any Department of Justice official obstructed justice by engaging in conduct intended to delay or impede the investigation of the RTC's criminal referral C-0004. -

White House Transition Interview

White House Interview Program DATE: December 29, 1999 INTERVIEWEE: GERALD RAFSHOON INTERVIEWER: Martha Kumar [Disc 1 of 1] MK: When you’d like to go off-the-record or on-background, that’s fine as well. Ultimately the material goes into a presidential library; it will go into the [Jimmy] Carter Library. We’re working with the National Archives on it. The full interviews don’t come out publicly until 2001, when a new President comes in, and also you’ve had a chance to go over the transcript. GR: Okay. MK: It’s going to be used in various ways. It’s a group of presidency scholars and we’re doing profiles of seven offices. We’ve selected seven offices. And we’ll go back over time to the [Richard] Nixon administration, and profile what the functions have been, the responsibilities, different ways in which they’ve been organized. I’m writing the one by myself on communications. I’m doing press and communications by myself. The pieces themselves are going to be short, although they’ll be on a pass-coded website for people coming in so they can then⎯in addition to reading the fifteen pages about some of the general things about the office⎯they’ll be able to select items within it as well. We’ll have links in to longer pieces. And then we’re doing what we call “Standards of a Successful Start” in the spring, which are isolating maybe eight elements that are common to successful transitions. GR: Interesting. Did you read Bob Woodward's latest book, Shadow: Five Presidents and the Legacy of Watergate? MK: Yes. -

White House Compliance with Committee Subpoenas Hearings

WHITE HOUSE COMPLIANCE WITH COMMITTEE SUBPOENAS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 6 AND 7, 1997 Serial No. 105–61 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform and Oversight ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 45–405 CC WASHINGTON : 1998 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Jan 31 2003 08:13 May 28, 2003 Jkt 085679 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HEARINGS\45405 45405 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT DAN BURTON, Indiana, Chairman BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York HENRY A. WAXMAN, California J. DENNIS HASTERT, Illinois TOM LANTOS, California CONSTANCE A. MORELLA, Maryland ROBERT E. WISE, JR., West Virginia CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut MAJOR R. OWENS, New York STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York CHRISTOPHER COX, California PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida GARY A. CONDIT, California JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York STEPHEN HORN, California THOMAS M. BARRETT, Wisconsin JOHN L. MICA, Florida ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, Washington, THOMAS M. DAVIS, Virginia DC DAVID M. MCINTOSH, Indiana CHAKA FATTAH, Pennsylvania MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland JOE SCARBOROUGH, Florida DENNIS J. KUCINICH, Ohio JOHN B. SHADEGG, Arizona ROD R. BLAGOJEVICH, Illinois STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois MARSHALL ‘‘MARK’’ SANFORD, South JOHN F. TIERNEY, Massachusetts Carolina JIM TURNER, Texas JOHN E. -

UN Chief Calls for More Efforts to End Violence in Syria

5 International UN Chief Calls for more Efforts to Neighbour News Li’s Visit Opens New End Violence in Syria Chapter in China-EU UNITED NATIONS - The and a high representa- Economic Ties international community tive from the European BEIJING - Chinese Pre- nomic structure, ana- should be shamed by Union, met in Geneva, mier Li Keqiang’s visit lysts believe integration the continued suffering Switzerland, to create to the European Union of their development of the Syrian people, UN a road map for peace in has resulted in a hoard strategies will boost the Secretary-General Ban Syria. of new trade deals, growth of both sides Ki-Moon said in a state- The conflict, which start- which are expected to and provide new oppor- ment issued here Tues- ed in March 2011, has left establish the highest tunities for China-EU day, the third anniversa- more than 220,000 Syr- level of bilateral eco- economic ties. ry of an agreement aimed ians dead, while almost nomic and trade coop- Zhao Junjie, a research at finding a political solu- half of the country’s eration to date. fellow at the Institute tion to end the conflict in population have been During Li’s visit, the of European Studies of the Middle East country. forced to flee their homes two economic giants the Chinese Academy “It should shame us all since three years ago, ac- expressed interest in of Social Sciences, said that, three years since the cording to Ban. Syria is linking the European connecting Chinese and adoption of the Geneva now the most unstable Fund for Strategic EU development strate- Communiqu on resolv- region in the world, de- Investments (EFSI), gies has become one of ing the cataclysmic con- clared Ban, saying it is known as the Juncker the highlights of Li’s Eu- flict in Syria, the suffer- “increasingly controlled Plan, with the China- rope visit. -

RLB Letterhead

6-25-14 White Paper in support of the Robert II v CIA and DOJ plaintiff’s June 25, 2014 appeal of the June 2, 2014 President Reagan Library FOIA denial decision of the plaintiff’s July 27, 2010 NARA MDR FOIA request re the NARA “Perot”, the NARA “Peter Keisler Collection”, and the NARA “Robert v National Archives ‘Bulky Evidence File” documents. This is a White Paper (WP) in support of the Robert II v CIA and DOJ, cv 02-6788 (Seybert, J), plaintiff’s June 25, 2014 appeal of the June 2, 2014 President Reagan Library FOIA denial decision of the plaintiff’s July 27, 2010 NARA MDR FOIA request. The plaintiff sought the release of the NARA “Perot”, the NARA “Peter Keisler Collection”, and the NARA “Robert v National Archives ‘Bulky Evidence File” documents by application of President Obama’s December 29, 2009 E.O. 13526, Classified National Security Information, 75 F.R. 707 (January 5, 2010), § 3.5 Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR). On June 2, 2014, President Reagan Library Archivist/FOIA Coordinator Shelly Williams rendered a Case #M-425 denial decision with an attached Worksheet: This is in further response to your request for your Mandatory Review request for release of information under the provisions of Section 3.5 of Executive Order 13526, to Reagan Presidential records pertaining to Ross Perot doc re report see email. These records were processed in accordance with the Presidential Records Act (PRA), 44 U.S.C. §§ 2201-2207. Id. Emphasis added. The Worksheet attachment to the decision lists three sets of Keisler, Peter: Files with Doc ## 27191, 27192, and 27193 notations. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CARA LESLIE ALEXANDER, ) et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Civil No. 96-2123 ) 97-1288 ) (RCL) FEDERAL BUREAU OF ) INVESTIGATION, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) ) MEMORANDUM AND ORDER This matter comes before the court on Plaintiffs’ Motion [827] to Compel Answers to Plaintiffs’ First Set of Interrogatories to the Executive Office of the President Pursuant to Court Order of April 13, 1998. Upon consideration of this motion, and the opposition and reply thereto, the court will GRANT the plaintiffs’ motion. I. Background The underlying allegations in this case arise from what has become popularly known as “Filegate.” Plaintiffs allege that their privacy interests were violated when the FBI improperly handed over to the White House hundreds of FBI files of former political appointees and government employees from the Reagan and Bush Administrations. This particular dispute revolves around interrogatories pertaining to Mike McCurry, Ann Lewis, Rahm Emanuel, Sidney Blumenthal and Bruce Lindsey. Plaintiffs served these interrogatories pertaining to these five current or former officials on May 13, 1999. The EOP responded on July 16, 1999. Plaintiffs now seek to compel further answers to the following lines of questioning: 1. Any and all knowledge these officials have, including any meetings held or other communications made, about the obtaining of the FBI files of former White House Travel Office employees Billy Ray Dale, John Dreylinger, Barney Brasseux, Ralph Maughan, Robert Van Eimerren, and John McSweeney (Interrogatories 11, 35, 40 and 47). 2. Any and all knowledge these officials have, including any meetings held or other communications made, about the release or use of any documents between Kathleen Willey and President Clinton or his aides, or documents relating to telephone calls or visits 2 between Willey and the President or his aides (Interrogatories 15, 37, and 42).