Evidence for the Austronesian Voyages in the Indian Ocean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Scores the Ocean Health Index Team Table of Contents

2015 GLOBAL SCORES THE OCEAN HEALTH INDEX TEAM TABLE OF CONTENTS Conservation International Introduction to Ocean Health Index ............................................................................................................. 1 Results for 2015 ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Country & Territory Scores ........................................................................................................................... 9 Appreciations ............................................................................................................................................. 23 Citation ...................................................................................................................................................... 23 UC Santa Barbara, National Center for Ecological Analysis & Synthesis INTRODUCTION TO THE OCEAN HEALTH INDEX Important note: Scores in this report differ from scores originally posted on the Ocean Health Index website, www.oceanhealthindex.org and shown in previous reports. Each year the Index improves methods and data where possible. Some improvements change scores and rankings. When such changes occur, all earlier scores are recalculated using the new methods so that any differences in scores between years is due to changes in the conditions evaluated, not to changes in methods. This permits year-to-year comparison between all global-level Index results. Only the scores most recently -

Florida Department of Education

)/25,'$ '(3$570(17 2) ('8&$7,21 ,PSOHPHQWDWLRQ 'DWH '2( ,1)250$7,21 '$7$ %$6( 5(48,5(0(176 )LVFDO <HDU 92/80( , $8720$7(' 678'(17 ,1)250$7,21 6<67(0 July 1, 1995 $8720$7(' 678'(17 '$7$ (/(0(176 APPENDIX G COUNTRY CODES CODE COUNTRY CODE COUNTRY AF Afghanistan CV Cape Verde AB Albania CJ Cayman Islands AG Algeria CP Central African Republic AN Andorra CD Chad AO Angola CI Chile AV Anguilla CH China AY Antarctica KI Christmas Island AC Antigua and Barbuda CN Clipperton Island AX Antilles KG Cocos Islands (Keeling) AE Argentina CL Colombia AD Armenia CQ Comoros AA Aruba CF Congo AS Australia CR Coral Sea Island AU Austria CS Costa Rica AJ Azerbaijan DF Croatia AI Azores Islands, Portugal CU Cuba BF Bahamas DH Curacao Island BA Bahrain CY Cyprus BS Baltic States CX Czechoslovakia BG Bangladesh DT Czech Republic BB Barbados DK Democratic Kampuchea BI Bassas Da India DA Denmark BE Belgium DJ Djibouti BZ Belize DO Dominica BN Benin DR Dominican Republic BD Bermuda EJ East Timor BH Bhutan EC Ecuador BL Bolivia EG Egypt BJ Bonaire Island ES El Salvador BP Bosnia and Herzegovina EN England BC Botswana EA Equatorial Africa BV Bouvet Island EQ Equatorial Guinea BR Brazil ER Eritrea BT British Virgin Islands EE Estonia BW British West Indies ET Ethiopia BQ Brunei Darussalam EU Europa Island BU Bulgaria FA Falkland Islands (Malvinas) BX Burkina Faso, West Africa FO Faroe Islands BM Burma FJ Fiji BY Burundi FI Finland JB Byelorussia SSR FR France CB Cambodia FM France, Metropolitian CM Cameroon FN French Guiana CC Canada FP French Polynesia Revised: -

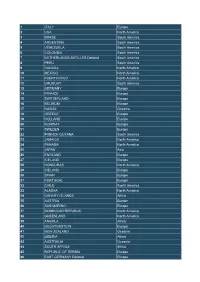

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

Diversity and Distribution of the Genus Dioscorea In

DIVERSITY AND DISTRIBUTION INTRODUCTION • The genus Dioscorea is one of the largest groups among OF THE GENUS DIOSCOREA IN monocotyledons belonging to the family Dioscoreaceae. • The members are commonly known as yams and are widely WESTERN GHATS cultivated for its edible tubers throughout tropics and occupies 3rd most important food crops in the world, next to cereals and pulses. • The word yams comes from Portuguese or Spanish name as “Inhame” which means “to eat”. Elsamma Joseph (Arackal) • The genus is distributed mainly in three centers of diversity A.G. Pandurangan & S. Ganeshan namely South Africa, South East Asia and Latin America. • The genus Dioscorea represents 850 spp. (Mabberley, 1997) and in India reported the occurrence of 32 spp. (Prain and Burkill, 1936, 1939) of which 17 are distributed in W. Ghats. • The genus shows close affinity towards dicotyledons by the presence of petiolate compound leaves, non sheathing leaf base, reticulate venation etc. Tropical Botanic Garden and Research Institute Palode, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala REASONS FOR UNDERTAKING THE REASONS FOR UNDERTAKING THE STUDY STUDY…….contd • The taxonomy of quite a few species in this genus is considered • Many of the Dioscorea species serve as a “life saving” plant to be very problematic ( Prain and Burkill, 1936, 1939; Velayudan, group to marginal farmers and forest dwelling communities 1998) due to their continuous variability of morphological during the period of food scarcity (Arora and Anjula pandey, characters especially in aerial parts such as leaves and bulbils. 1996) This makes it difficult for taxonomists to segregate distinctly the various taxa of the genus. • Most of the tubers are edible and few are also used as medicinal. -

Florida Department of Education

FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Implementation Date: DOE INFORMATION DATA BASE REQUIREMENTS Fiscal Year 1995-96 VOLUME II: AUTOMATED STAFF INFORMATION SYSTEM July 1, 1995 AUTOMATED STAFF DATA ELEMENTS APPENDIX C COUNTRY CODES CODE COUNTRY CODE COUNTRY AF Afghanistan CV Cape Verde AB Albania CJ Cayman Islands AG Algeria CP Central African Republic AN Andorra CD Chad AO Angola CI Chile AV Anguilla CH China AY Antarctica KI Christmas Island AC Antigua and Barbuda CN Clipperton Island AX Antilles KG Cocos Islands (Keeling) AE Argentina CL Colombia AD Armenia CQ Comoros AA Aruba CF Congo AS Australia CR Coral Sea Island AU Austria CS Costa Rica AJ Azerbaijan DF Croatia AI Azores Islands, Portugal CU Cuba BF Bahamas DH Curacao Island BA Bahrain CY Cyprus BS Baltic States CX Czechoslovakia BG Bangladesh DT Czech Republic BB Barbados DK Democratic Kampuchea BI Bassas Da India DA Denmark BE Belgium DJ Djibouti BZ Belize DO Dominica BN Benin DR Dominican Republic BD Bermuda EJ East Timor BH Bhutan EC Ecuador BL Bolivia EG Egypt BJ Bonaire Island ES El Salvador BP Bosnia and Herzegovina EN England BC Botswana EA Equatorial Africa BV Bouvet Island EQ Equatorial Guinea BR Brazil ER Eritrea BT British Virgin Islands EE Estonia BW British West Indies ET Ethiopia BQ Brunei Darussalam EU Europa Island BU Bulgaria FA Falkland Islands (Malvinas) BX Burkina Faso, West Africa FO Faroe Islands BM Burma FJ Fiji BY Burundi FI Finland JB Byelorussia SSR FR France CB Cambodia FM France, Metropolitian CM Cameroon FN French Guiana CC Canada FP French Polynesia Revised: -

Meroz-Plank Canoe-Edited1 Without Bold Ital

UC Berkeley Survey Reports, Survey of California and Other Indian Languages Title The Plank Canoe of Southern California: Not a Polynesian Import, but a Local Innovation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1977t6ww Author Meroz, Yoram Publication Date 2013 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Plank Canoe of Southern California: Not a Polynesian Import, but a Local Innovation YORAM MEROZ By nearly a millennium ago, Polynesians had settled most of the habitable islands of the eastern Pacific, as far east as Easter Island and as far north as Hawai‘i, after journeys of thousands of kilometers across open water. It is reasonable to ask whether Polynesian voyagers traveled thousands of kilometers more and reached the Americas. Despite much research and speculation over the past two centuries, evidence of contact between Polynesia and the Americas is scant. At present, it is generally accepted that Polynesians did reach South America, largely on the basis of the presence of the sweet potato, an American cultivar, in prehistoric East Polynesia. More such evidence would be significant and exciting; however, no other argument for such contact is currently free of uncertainty or controversy.1 In a separate debate, archaeologists and ethnologists have been disputing the rise of the unusually complex society of the Chumash of Southern California. Chumash social complexity was closely associated with the development of the plank-built canoe (Hudson et al. 1978), a unique technological and cultural complex, whose origins remain obscure (Gamble 2002). In a recent series of papers, Terry Jones and Kathryn Klar present what they claim is linguistic, archaeological, and ethnographical evidence for prehistoric contact from Polynesia to the Americas (Jones and Klar 2005, Klar and Jones 2005). -

Wao Kele O Puna Comprehensive Management Plan

Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan Prepared for: August, 2017 Prepared by: Nālehualawaku‘ulei Nālehualawaku‘ulei Nā-lehua-lawa-ku‘u-lei is a team of cultural resource specialists and planners that have taken on the responsibilities in preparing this comprehensive management for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Nā pua o kēia lei nani The flowers of this lovely lei Lehua a‘o Wao Kele The lehua blossoms of Wao Kele Lawa lua i kēia lei Bound tightly in this lei Ku‘u lei makamae My most treasured lei Lei hiwahiwa o Puna Beloved lei of Puna E mālama mākou iā ‘oe Let us serve you E hō mai ka ‘ike Grant us wisdom ‘O mākou nā pua For we represent the flowers O Nālehualawaku‘ulei Of Nālehualawaku‘ulei (Poem by na Auli‘i Mitchell, Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i) We come together like the flowers strung in a lei to complete the task put before us. To assist in the preservation of Hawaiian lands, the sacred lands of Wao Kele o Puna, therefore we are: The Flowers That Complete My Lei Preparation of the Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan In addition to the planning team (Nālehualawaku‘ulei), many minds and hands played important roles in the preparation of this Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan. Likewise, a number of support documents were used in the development of this plan (many are noted as Appendices). As part of the planning process, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs assembled the ‘Aha Kūkā (Advisory Council), bringing members of the diverse Puna community together to provide mana‘o (thoughts and opinions) to OHA regarding the development of this comprehensive management plan (CMP). -

Micronesica 38(1):93–120, 2005

Micronesica 38(1):93–120, 2005 Archaeological Evidence of a Prehistoric Farming Technique on Guam DARLENE R. MOORE Micronesian Archaeological Research Services P.O. Box 22303, GMF, Guam, 96921 Abstract—On Guam, few archaeological sites with possible agricultural features have been described and little is known about prehistoric culti- vation practices. New information about possible upland planting techniques during the Latte Phase (c. A.D. 1000–1521) of Guam’s Prehistoric Period, which began c. 3,500 years ago, is presented here. Site M201, located in the Manenggon Hills area of Guam’s interior, con- tained three pit features, two that yielded large pieces of coconut shell, bits of introduced calcareous rock, and several large thorns from the roots of yam (Dioscorea) plants. A sample of the coconut shell recovered from one of the pits yielded a calibrated (2 sigma) radiocarbon date with a range of A.D. 986–1210, indicating that the pits were dug during the early Latte Phase. Archaeological evidence and historic literature relat- ing to planting, harvesting, and cooking of roots and tubers on Guam suggest that some of the planting methods used in historic to recent times had been used at Site M201 near the beginning of the Latte Phase, about 1000 years ago. I argue that Site M201 was situated within an inland root/tuber agricultural zone. Introduction The completion of numerous archaeological projects on Guam in recent years has greatly increased our knowledge of the number and types of prehis- toric sites, yet few of these can be considered agricultural. Descriptions of agricultural terraces, planting pits, irrigation canals, or other agricultural earth works are generally absent from archaeological site reports, although it has been proposed that some of the piled rock alignments in northern Guam could be field boundaries (Liston 1996). -

Table 1 Comprehensive International Points List

Table 1 Comprehensive International Points List FCC ITU-T Country Region Dialing FIPS Comments, including other 1 Code Plan Code names commonly used Abu Dhabi 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Aden 5 967 YE include with Yemen Admiralty Islands 7 675 PP include with Papua New Guinea (Bismarck Arch'p'go.) Afars and Assas 1 253 DJ Report as 'Djibouti' Afghanistan 2 93 AF Ajman 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Akrotiri Sovereign Base Area 9 44 AX include with United Kingdom Al Fujayrah 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Aland 9 358 FI Report as 'Finland' Albania 4 355 AL Alderney 9 44 GK Guernsey (Channel Islands) Algeria 1 213 AG Almahrah 5 967 YE include with Yemen Andaman Islands 2 91 IN include with India Andorra 9 376 AN Anegada Islands 3 1 VI include with Virgin Islands, British Angola 1 244 AO Anguilla 3 1 AV Dependent territory of United Kingdom Antarctica 10 672 AY Includes Scott & Casey U.S. bases Antigua 3 1 AC Report as 'Antigua and Barbuda' Antigua and Barbuda 3 1 AC Antipodes Islands 7 64 NZ include with New Zealand Argentina 8 54 AR Armenia 4 374 AM Aruba 3 297 AA Part of the Netherlands realm Ascension Island 1 247 SH Ashmore and Cartier Islands 7 61 AT include with Australia Atafu Atoll 7 690 TL include with New Zealand (Tokelau) Auckland Islands 7 64 NZ include with New Zealand Australia 7 61 AS Australian External Territories 7 672 AS include with Australia Austria 9 43 AU Azerbaijan 4 994 AJ Azores 9 351 PO include with Portugal Bahamas, The 3 1 BF Bahrain 5 973 BA Balearic Islands 9 34 SP include -

The Canoe Is the People LEARNER's TEXT

The Canoe Is The People LEARNER’S TEXT United Nations Local and Indigenous Educational, Scientific and Knowledge Systems Cultural Organization Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 1 14/11/2013 11:28 The Canoe Is the People educational Resource Pack: Learner’s Text The Resource Pack also includes: Teacher’s Manual, CD–ROM and Poster. Produced by the Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS) Programme, UNESCO www.unesco.org/links Published in 2013 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France ©2013 UNESCO All rights reserved The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Coordinated by Douglas Nakashima, Head, LINKS Programme, UNESCO Author Gillian O’Connell Printed by UNESCO Printed in France Contact: Douglas Nakashima LINKS Programme UNESCO [email protected] 2 The Canoe Is the People: Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 2 14/11/2013 11:28 contents learner’s SECTIONTEXT 3 The Canoe Is the People: Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 3 14/11/2013 11:28 Acknowledgements The Canoe Is the People Resource Pack has benefited from the collaborative efforts of a large number of people and institutions who have each contributed to shaping the final product. -

Lilioceris Egena Air Potato Biocontrol Environmental Assessment

United States Department of Field Release of the Beetle Agriculture Lilioceris egena (Coleoptera: Marketing and Regulatory Chrysomelidae) for Classical Programs Biological Control of Air Potato, Dioscorea bulbifera (Dioscoreaceae), in the Continental United States Environmental Assessment, February 2021 Field Release of the Beetle Lilioceris egena (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) for Classical Biological Control of Air Potato, Dioscorea bulbifera (Dioscoreaceae), in the Continental United States Environmental Assessment, February 2021 Agency Contact: Colin D. Stewart, Assistant Director Pests, Pathogens, and Biocontrol Permits Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd., Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. Additional information can be found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_file.html. To File a Program Complaint If you wish to file a Civil Rights program complaint of discrimination, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form (PDF), found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html, or at any USDA office, or call (866) 632-9992 to request the form. -

Yam Physic-Chemical Parameters Assessment and Its Bread Sensory Attributes for Corporate Agribusiness Boosting

Journal of Nutritional Health & Food Engineering Research Article Open Access Yam physic-chemical parameters assessment and its bread sensory attributes for corporate agribusiness boosting Abstract Volume 8 Issue 6 - 2018 A research work entitled: “Yam physico-chemical parameters assessment and its bread Francis Dominicus Nzabuheraheza, Anathalie sensory attributes.” was carried out in the laboratory of INES-Ruhengeri for adding value to local yam called Dioscorea spp. The main objective was to assess physico-chemical Niyigena Nyiramugwera, Tombola M Gustave Department of Biotechnologies, Rwanda parameters of fresh yam tubers and sensory attributes of produced bread from yam fermented flour. A sample size of 10kg of eachDioscorea variety as fresh crude yam tubers Correspondence: Francis Dominicus Nzabuheraheza, was brought from Musanze market to INES laboratory for chemical analysis, fermentation Department of Biotechnologies, Faculty of Applied Fundamental and bread processing. Physico-chemical parameters analyzed in fresh crude yam tubers Sciences (FAFS), Higher Institute of Education, Rwanda, included moisture content, pH, nutrient content and sensory evaluation of yam bread. The Email results showed that fresh crude yam tubers moisture content ranged from 75 to 77%. This moisture content is favoring yam tubers spoilage and there is a need to process fresh yams Received: March 16, 2018 | Published: November 23, 2018 into bread for adding value. The yielded fermented yam flour ranged from 18 to 20% from crude yam tubers. The dried and fermented yam flour moisture content was around 13% and met the standards, while pH was around neutral (from 6.66 to 6.72) leading to tubers deterioration. The flour had a dark-brown color from enzymatic browning occurring during fermentation process.